Edi Hila, “Paysages Transitionnels”, Galerie JGM, Paris, January 15, 2009 – February 15, 2009.

Edi Hila: Paysages Transitionnels, Galerie JGM, Paris. January 15, 2009 – February 15, 2009

Ever since the fall of the Berlin Wall, Edi Hila has been known in the international art community as one of the most remarkable artists of his generation. Hila is known as a professor to numerous generations of young students at Tirana’s Academy of Fine Arts (among whom Anri Sala, Adrian Paci and Tirana’s infamous mayor-painter Edi Rama). He is admired for his gentle character and precise knowledge by those privileged enough to have known him personally or to have worked with him. And he is appreciated by everyone for his subtle and detailed gestures, as well as for his painting whose scope reaches from visionary and dark to documentary.

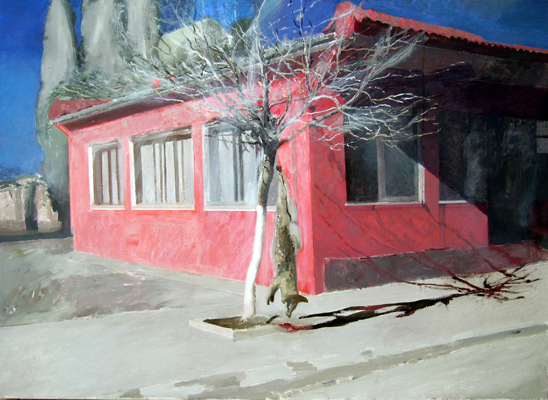

The many half-built houses that dot the outskirts of Albania’s cities have given Hila a rich field for inspiration. Overgrown by grass and unfinished, the only thing we see of these houses is their phantasmagoric facades that make us wonder how much of what we observe is real, and where Hila’s interventions begin. The focal point in Hila’s paintings in general is always in the middle of the image. Hila’s use of central perspective is a reminiscence of his appreciation of those Renaissance and religious paintings that portray their subjects and objects with a dignified distance, but also with sincere and expressive admiration. When he starts developing an idea for a painting, Hila usually begins by taking a large number of photographs of the situations he encounters on the streets of Tirana or in the wild landscape around Albania. The many paradoxical details Hila captures in this way are then transferred to canvas in a palette that favors gray over the original matte colours. This allows the artist, as he himself has said, to render the dust and dirt of the landscape with a higher degree of realism. Apart from that, the prevailingly beige, gray and brown palette permits him to tease out metaphysical dimensions in the depicted scenes and objects. Crucially, Hila is not simply a documentarist; he also keenly registers the anecdotal, inventive and fictional elements that traverse reality.

Upon his 1973 return from Italy where he had spent two months as an intern at the Italian television network RAI, Hila was accused of producing deviationist paintings and was forced to undergo a regimen of Communist re-education in the form of forced physical labour. He took up painting again only during the 1990-ies. In 2007 Hila returned to Italy for the first time. Dog in the Garden, an enigmatic painting of a terracotta dog with slightly visible cracks on his forehead that sits by a stream in an enchanted garden (an allusion to Cerberus in Dante’s Inferno), was the result of the artist’s return to the birthplace of the Renaissance. As Hila has disclosed, it was his reminiscences of the Renaissance that kept him alive during the painful years under totalitarianism.

Upon his 1973 return from Italy where he had spent two months as an intern at the Italian television network RAI, Hila was accused of producing deviationist paintings and was forced to undergo a regimen of Communist re-education in the form of forced physical labour. He took up painting again only during the 1990-ies. In 2007 Hila returned to Italy for the first time. Dog in the Garden, an enigmatic painting of a terracotta dog with slightly visible cracks on his forehead that sits by a stream in an enchanted garden (an allusion to Cerberus in Dante’s Inferno), was the result of the artist’s return to the birthplace of the Renaissance. As Hila has disclosed, it was his reminiscences of the Renaissance that kept him alive during the painful years under totalitarianism.

The emotionally charged and vivid portrait La Mama shows the profile of the painter’s mother sitting and pointing with a remote control towards an invisible television set. The painting suggests an almost painful identification with what the portrayed represents. The mother is surrounded by an indefinite dark gray space that alludes to the possibility that her pointing gesture might be one of the last activities of her life. Hila’s iconic image of everybody’s grandmother is one of the very rare occasions in Hila’s work when he portrays people. It reveals with great intensity the master’s persuasive ability to make his audience vulnerable.

The emotionally charged and vivid portrait La Mama shows the profile of the painter’s mother sitting and pointing with a remote control towards an invisible television set. The painting suggests an almost painful identification with what the portrayed represents. The mother is surrounded by an indefinite dark gray space that alludes to the possibility that her pointing gesture might be one of the last activities of her life. Hila’s iconic image of everybody’s grandmother is one of the very rare occasions in Hila’s work when he portrays people. It reveals with great intensity the master’s persuasive ability to make his audience vulnerable.