East of Art: Transformations in Eastern Europe: “What Comes After the Wall?”

My presentation is entitled “11/9, or Wrestling with Context.” The date 11/9 is not a mistake and I am not going to talk about 9/11 in New York, but rather about November 11, 1989, the date when the Berlin Wall fell.

In my 15 minutes, I would like to present an abbreviated version of the four best years of my professional life. Namely, in 1997, David Elliott, who was then the Director of the Moderna Museet (Museum of Modern Art) in Stockholm, invited me to be Chief Curator of the project “After the Wall – Art and Culture in post-Communist Europe.”

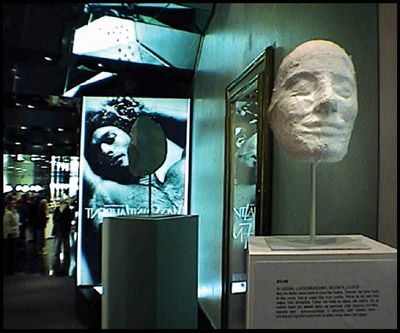

During the following four years I was researching, then curating, then installing the exhibition “After the Wall”, held in the Moderna Museet Stockholm between October 16, 1999 and January 16, 2000. The exhibition was accompanied by other events (performances, symposium, video and film screenings). After the Wall was later shown in Museum Ludwig in Budapest (2000) and finally in Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin (2000/2001).

The “After the Wall” exhibition marked a ten-year anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. I mean, of course, the physical removal of the Wall. The Wall was removed as a physical object, but pieces of it stayed in people’s mind-both in the West and in the East.

In Germany, where West Germans called themselves the “Wessies”, and East Germans “Ossies”, the show was received in various ways. One German art critic even wrote a negative review of the exhibition called “‘Ossies’ Horror Picture Show.” I did not personally mind this title, as I understood it as good “propaganda” for the exhibition.

The first artwork the visitors encountered when attending the show was a sound installation placed outside the museums’ buildings in Stockholm, Budapest and Berlin. This is the sound you can hear now. The artist who produced this work is the only “Wessi” in the exhibition, Lutz Becker who was born in Berlin but lives in London.

Lutz Becker, After the Wall, 1999

Sound installation

The sound projection is a montage of archival recordings by the radio station Sender Freies Berlin (SFB) at the Berlin Wall in the weeks immediately after its opening in November 1989. The eerie sound of the gradual erosion of the Wall brought about by hundreds of people, “die Mauersprechte,” attacking the concrete structure with their own hammers and chisels. This sound montage included the recordings taken at various venues in Berlin, such as Potsdamer Platz, Invalidenstrasse, Checkpoint Charlie and the Brandenburg Gate.

“After the Wall” was an art exhibition produced in 21 and one half post-Communist countries. By “a half” I mean the GDR, which became reunited with West Germany. When we approach any such a project dealing with non-Western art we usually (over) use the term “context.” Namely, the presumption is that art from non-Western regions could not be understood unless we, curators, know the “context” in which it is produced.

|  |  |

Sanja Ivekovich, “Women’s House”, View of the Installation, 1997

Thus, the curators active in the post-Communist world often complain that the Western curators do not understand ‘our’ context. Western curators, on the other hand, claim that they are not including eastern artists in their exhibitions in Western institutions because, as the argument goes, Western audiences don’t comprehend the context enough to understand such art. In the introduction to the anthology Primary Documents, Mr. Ilya Kabakov reiterates this idea.

So I always asked myself why we insist on the notion “context” only when we speak of non-Western contemporary art. Historically speaking, we often forget that we refer to art movements specifically, going so far as to study “Zurich Dada” and “Berlin Dada.”

When we studied performance art in America in the ’70’s for instance, we also speak about performance in California and performance in New York. So implicitly we spoke about the context. This means that Dada in these cities was different from other forms of Dada, and that performance in California was definitely different from performance in other parts of the States.

Nonetheless, today the “context” became a magic term for evaluating and dis-evaluating contemporary productions that come from the non-Euro-American art world. The question is why we presume that only when the audience knows the “context” it would be able to “understand” art in Eastern Europe, Central Europe or Russia.

The main questions that puzzle me are: First, can an (“Eastern”) artwork simply be reduced to the “context” in which it was produced. And second, what remains in/of this artwork if we take it away from “the context”?

The first frustrating thing for every curator is that one cannot exhibit context. Laura Hoptman, who curated the exhibition “Beyond Belief” (1995) held in Chicago, knows the problem very well. What we can do is exhibit works of art. Works of art cannot illustrate the Eastern, Post-Communist “context.” Works of art are only works of art-nothing more. This means that works of art possess layers of meaning that go beyond or above the given political, social and economic “context.” Otherwise we would consider them works of art.

A good example for me is the reception of Ilya Kabakov’s art in the West. His art was so well received despite the fact that people (even his curators themselves) were not fully familiar with the “real context” behind his installations. Of course, part of the reception is also the reading of Kabakov’s art provided by Mr. Boris Groys.

But Western audiences (who may have not read the catalogue texts) reacted to this art and considered it, as I myself do, good. Why? Because a work of art has a real presence. In Kabakov’s case, there is a certain “visual correctness” to his installations and other works that make the viewers react. You enter the exhibition space and the work is there. It functions: people “get” something in front of it, they feel something, they are troubled with something and perhaps are irritated. This is to say that the work of art “works” even if you don’t exactly know the context.

When we started to prepare “After the Wall”, we were very concerned about the “context.” And the “context” we had to deal with was a vast territory consisting of 21 various “contexts” depending on the respective country. In addition, the “context” existing in the reunited Germany has its own completely unique dynamics.

Then, of course, there was the problem of how to define the very term “context.” For me, context is not something that exists “over there”, as an “objective reality” or as “truth” waiting to be unveiled by a (benevolent) curator who is open-to-the context which he or she does not know.

Before I became involved in this project I did not have a slightest idea about Armenian or Belorusian contemporary art. And I did not learn about these “contexts” from the works of art made by Armenian and Belorusian artists, but from reading about history, about the post-Communist age of economic “transition,” conditions of artistic production, local art criticism and theory etc.

In other words, I did not expect artists to “illustrate” the local context. My concern as a curator was to try to find good works of art. When we curate exhibitions, write about contemporary art, and install our shows we in fact construct a certain context, or provide a certain “frame” (in the Derridean sense) for the art we exhibit. Another curator or writer could invent a completely different “context” when curating/writing about the very same artists.

The “After the Wall” project passed through different stages. David Elliott and Iris Muller-Westerman from Moderna Musset and myself traveled for one year and a half visiting 23 post-Socialist states, after which we selected about 127 works made by 140 artists.

The exhibition did not intend to reinstate an idea of “another Europe”-a view shared by both western and eastern intellectuals during the Cold War. The exhibition focused on the individual artistic attitudes. It indicates the differences between individual positions and suggests their common traits.

Each artist was invited to show one or two particular works, and a few of them were asked to produce a special piece for the show. These were painters, sculptors, those who made installations, photographers, performers and video artists who emerged in the 1990s.

The curatorial intentions, however, were not directed towards creating the generation gaps and therefore a number of older artists who were active in the last ten years either locally or internationally, were also included. (The oldest artist was born 1937, the youngest 1972.)

Given the fact that all of them were born or still live in the Eastern Europe, and keeping in mind the number of participating artists, one art critic from Berlin commented: “After the Wall is something like Ossies’ documenta, isn’t it?”

After the selection of works was completed in March 1999, my dream about an exhibition having special thematic units became true. These themes were not chosen a priori, but were formulated only after the artists and their works have been selected. Only then did it become clear that all different individual productions could be thematically organized in the following way:

Social Sculpture. Under this title borrowed from Joseph Beuys, we gathered installations, photographic series and videos which critically dealt with themes related to various aspects of the “given” post-Communist realities, be they social economy, religion, race, nationalism, the “nouveuax riches” (new bourgeoisie) and the “nouveaux pauvres” (new poverty), consumerism and the impact of mass media.

Frank Thiel (Germany):Wachregiment Friedrich Engels (Friedrich Engels Guards Regiment) 1990

Frank Thiel (Germany): City 7/09 (1998)

Erchart Miklosh (Hungary) and Dominic Hislop (England): Inside Out, 1998

Josif Kiraly (Romania): Indirect-Bucharest 1993-1997

Boris Michailov (Ukraine), At Dusk, 1993

Nedko Solakov (Bulgaria): The New Ones, 1996

Arsen Savadov and Oleksndr Kharchenko (Ukraine): Deep Insider, 1998

Audrius Novickas (Lithuania): Old Legends Newly Tested, 1995

Dragoljub Rasa Todosijevic (FR Yugoslavia): Gott liebt die Serben (God Loves the Serbs), 1999-2000.

IRWIN (Slovenia): Transnationala, 1998

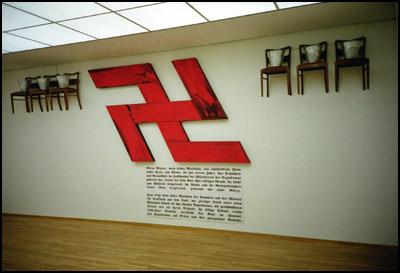

Giedrius Kumetaitis/ Mindaugas Ratavicius (Lithuania), Welcome, 1997Re-inventing the Past .This section includes those works that refer to the past, the Second World War, the Holocaust, or Communist totalitarian ideology. The “boom” of history that occurred immediately after 1989 is now over. In the early 1990s, so many artists tried to deal with the Communist project by exploiting the iconographic patterns and symbols of the previous regimes. In the late 1990s, though, the approach towards history became more sophisticated but equally critical.

Zbignev Libera (Poland): Lego Concentration Camp, 1996

Tomasz Kizny (Poland), The Sentenced, 1994

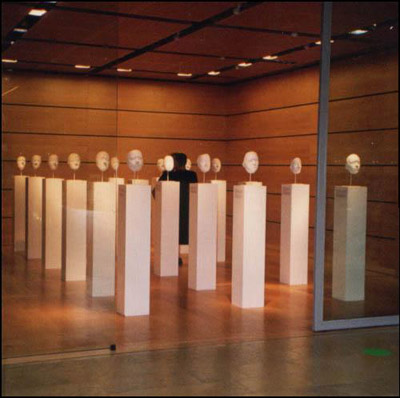

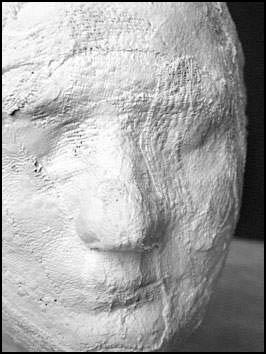

Galina Moskaleva (Belarus), The Chernobyl Project, 1996Questioning Subjectivity. This “chapter” of the exhibition consists of artworks in which the artists (often using self-portraits) rethink their social role or put in question the modernist notions of artistic ego, in a self-ironical but also in a self-mythologizing manner.

Nebojsa Seric-Soba (Bosnia and Herzegovina): Untitled, 1998

Kriszta Nagy (Hungary): I am a Contemporary Painter, 1999Genderscapes is a general term covering the works in which artists discuss implicitly or covertly the gender roles (femininity and masculinity), the human body, violence over the body (such as home violence), illness and mortality. As in the previous section, a number of works are based on self-representation.

Tatyana Antoshina (Russia), Promenade, 1997

Sanja Ivekovic (Croatia), Women’s House (1998, work in progress)

Jiri Cernicky (Czeck Republic), Flower Bruises, 1988

March 23, 2003

© Museum of Modern Art, New York

[su_menu name=”East of Art”]