Domestic Strategies by Women in Contemporary Hungarian Art (Article)

“Where are the women artists of Venice?” asked the Guerilla Girls in 2005. After investigating the ratio of woman artists exhibited in the most famous Venetian museum collections, they concluded that they are “underneath the men.” They communicated this in a humorous way on one of their posters exhibited at the Venice Biennale, placed above the following data: “of more than 1,238 artworks currently on view inthe major museums of Venice, fewer than 40 are by women.” Even earlier, the Guerilla Girls concluded that the situation in Europe is worse than in the United States (“It’s even worse in Europe,” 1989), and they haven’t been to Hungary yet.

In socialist Hungary in the fifties, despite the propaganda for equality, the proportion of female students in higher education was only twenty five percent. This numerical ratio grew slowly, and after the political transformation of 1989 it got close to fifty percent-in arts training as well-and after the millennium it even passed fifty percent. While sixty percent of the students at the Hungarian University of Fine Arts(At the moment, five universities provide arts training in Hungary.) are women, the proportion is only about twenty four percent among the instructors.(This includes the entire linguistics department; however, there are no female art department chairs. Only the library, the president’s office and the office of education are lead by women.) In addition, there are no professors at the institution among the women who teach there. This patriarchal setup is backed up by the fact that among art universities in Hungary there has only been one female President: Judit Droppa, textile designer at the University of Arts and Design between 1999 and 2006.

The Lexicon of Contemporary Hungarian Art (1999-2001), a collection of artists after World War II, counted 5901 artists, twenty five percent of whom are women. However, only nineteen percent of all the artists who have received the Mihály Munkácsy Award are women.(The Munkácsy Award is still the highest state-issued medium category award in the arts.) These numbers also testify to unequal opportunities; the fact that twenty five percent of woman artists are textile designers, eighteen percent are ceramists, fourteen percent are painters or graphic artists, twelve percent are sculptors, eleven percent are other industrial artists, four percent are architects or interior designers, and two percent are photographers, also suggests the conservation of traditional “female” roles.

The number of woman artists in the field has grown since the nineties. This is despite the fact that there has been no radical change in the institutional system of arts with the political transformation. Indeed there has been a conservative turn when it comes to gender roles.(The situation is similar in other European, ex-socialist countries. Some of the studies in the catalogue for the recent Gender Check exhibition also report on this. See Bojana Peji?, ed., Gender Check: Feminity and Masculinity in the Art of Eastern Europe, (Wien: Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig, 2009). See Suzana Milevsk, “The ‘Silkworm Cocoon’. Gender Difference and the Impact of Visual Culture on Contemporary Art in the Balkans,” in Gender Check, 195. See also Piotr Piotrowski, “Gender after the Wall” in Gender Check, 200.)

There is rather little gender-conscious and even less explicitly feminist(However, what has been called “latent” feminism is present in Hungary as well. See Zora Rusinová “The Totalitarian Period and Latent Feminism” in Praesens: Central European Contemporary Art Review No. 4 (2003): 5–12.) visual art in Hungary.(The situation of art theoreticians and historians is similar. While there are more and more women in the field, there are very few who take up the issues of woman-centered art history writing and art theory. This is partly due to conservative professional traditions, the socialization of women, and most importantly resistance from a field dominated by men.) Therefore, I am going to present recently created and exhibited works by women artists whose works–almost exclusively–are connected to the lives of women. They are dealing withtheir own situation and search for identity. The questions they raise are in no way unimportant, nor can they be considered private business. These artists represent an artistic attitude that is generally different from that of men. They mend and stitch together the tear between art and life–confirming that art is both part of our lives and about our lives. These artists reveal different slices of life from different walks of life. Their works are connected by the fact that their theme is women’s experience.

Naturally, the four artists I want to deal with here do not cover the contemporary Hungarian female art scene as a whole. Rather, the selection of different examples should imply the versatile nature of the art of women. I consciously chose a variety of artistic achievements to present the different attitudes of woman artists, and how they reflect the various aspects of female experience.

This section of the essay introduces the actual works, framing them around the activity of household work, from “The variety of household work is…” (Kriszta Nagy) through “breaking the eternal circulation of dirty laundry” (Ágnes Eperjesi).

Kriszta Nagy

Many people find Kriszta Nagy’s images scandalous. However it is not the work that is scandalous, but rather what it deals with: that women are censured, raped, used and dispossessed (The only chance for a woman is to be the puppet of a man). The texts accompanying her images are shockingly intolerable and unprintable (e. g. her series of prints Cover of the unpublished CD record) and they talk about forbidden things. But why are millions of women forced to bear what the printing ink is so fastidious about?

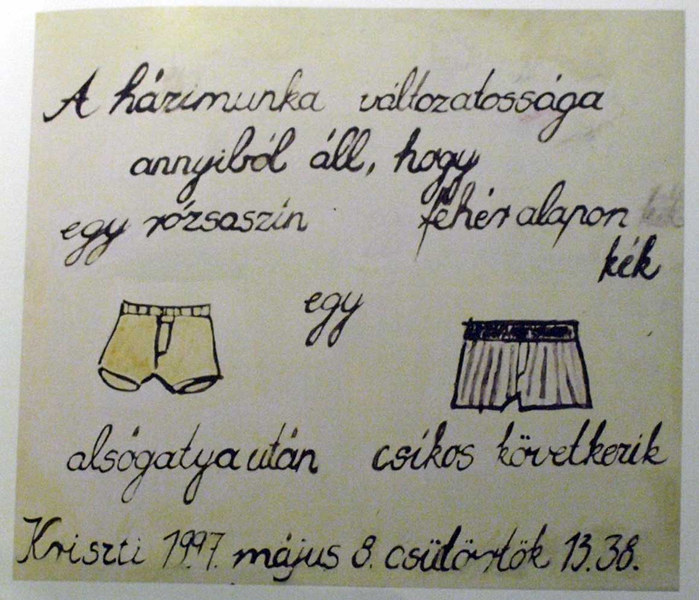

Nagy rebels against inequalities in sexuality and against being treated as a sexual object. This is also what she does when she recalls our inner child with her style, acting like a teenage girl who is defenseless, and who yearns for unconditional love. She articulates what few people say out loud (out of fear, ignorance or because of unconscious disincentive), even if they are aware of it. Nagy occasionally speaks ironically about the boredom of the undervalued domestic work imposed on women: The variety of household work is that after a pink underwear you can wash a striped white one, she wrote in one of her paintings (1997).

Nagy rebels against inequalities in sexuality and against being treated as a sexual object. This is also what she does when she recalls our inner child with her style, acting like a teenage girl who is defenseless, and who yearns for unconditional love. She articulates what few people say out loud (out of fear, ignorance or because of unconscious disincentive), even if they are aware of it. Nagy occasionally speaks ironically about the boredom of the undervalued domestic work imposed on women: The variety of household work is that after a pink underwear you can wash a striped white one, she wrote in one of her paintings (1997).

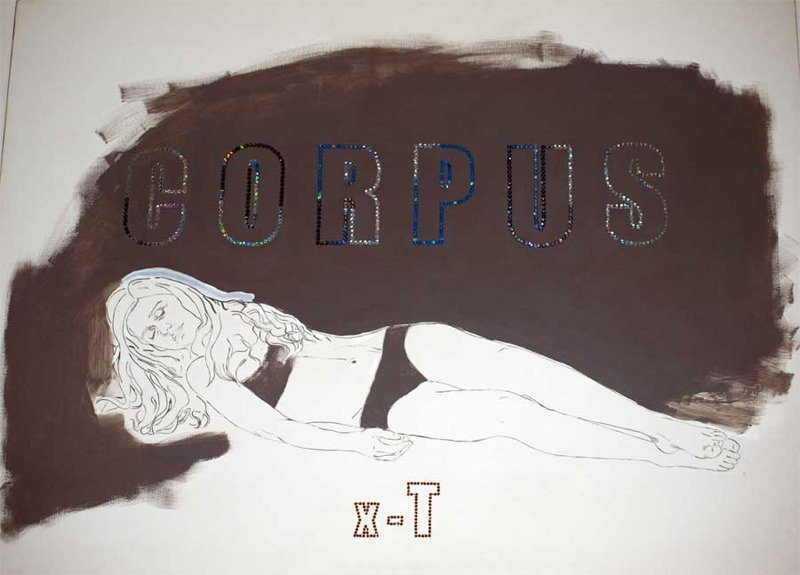

Nagy demonstrates a commodified understanding of the female body (HUF 200 000) when she presents herself in six almost identical Venus-in-Fur type pictures. Thanks to computer manipulation her uncovered breasts are different in all six images. Nagy is not afraid of taking risks. Her somewhat exhibitionist attitude–she appears herself on almost all of her pictures–is a manifestation of the fact that she doesn’t shun responsibility: she is part of the situation she depicts. Her signature, x-T (pronounced Christy), is the inflected form of Christ (in Latin), and it refers to her Christ-like role.

On her painting Corpus Kriszti–viewed from a cultural-historical perspective–Nagy reinterprets the Christian cultural heritage in a blasphemous way. She takes up the pain of the world as a cultural hero(ine), and instead of the body of Christ–the title’s meaning–she depicts her own dead body. In one of her series (The Thing Which No One Wants, 2008) Nagy shows her wounds in a sexy pose. The canvas is torn open in certain places and stitched up like a wound. This makes the body’s abuse tangible.

Nagy collides a visual language that is decorative, childish, painterly, vividly colored, or taken from commercial photography with colloquial speech. This can be youthful or obscene. Nagy plays with the contradictions between the two in an effort to dismantle a series of negative stereotypes about women.

Ágnes Szépfalvi

There is nothing subversive about Ágnes Szépfalvi’s narrative images, their setting or composition. She paints scenes taken from a women’s life in the manner that her sources, movies, commercials, and photos mediate them for us. In her pictorial world, scenes from everyday life are subtly reinterpreted and, due to this, they lose their “movie reality.” Szépfalvi paints women by placing them in thousands of stereotypical roles. Her models are sometimes her own daughters, and she rarely paints self-portraits. Even when she does, this fact remains concealed.

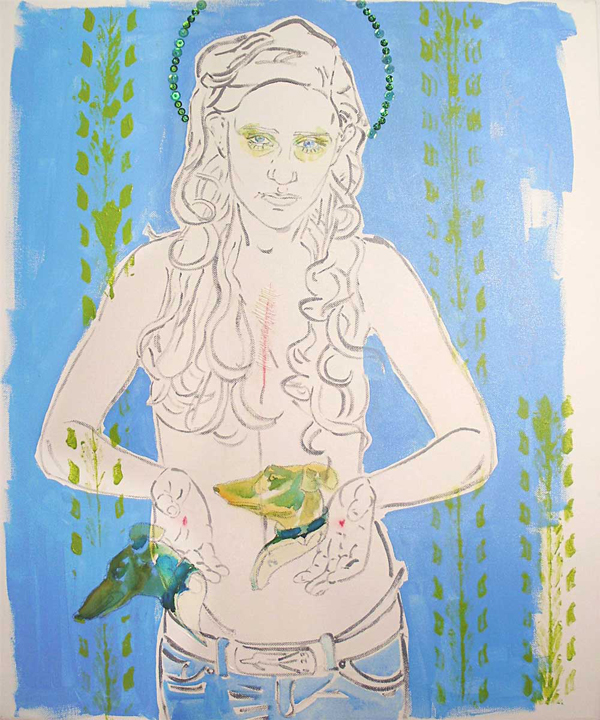

Szépfalvi’s exhibition The Beauty and the Beast was not different from her previous exhibitions, neither in terms of her pictorial style nor in terms of her movie-like visual world. The show included a narrative and some mythological archetypes. A common theme connects these images to the theme of sexual abuse. The motif of violence appears in various guises, from mythological painting with an idyllic color composition to emblem-like compositions or genre painting.

Szépfalvi’s exhibition The Beauty and the Beast was not different from her previous exhibitions, neither in terms of her pictorial style nor in terms of her movie-like visual world. The show included a narrative and some mythological archetypes. A common theme connects these images to the theme of sexual abuse. The motif of violence appears in various guises, from mythological painting with an idyllic color composition to emblem-like compositions or genre painting.

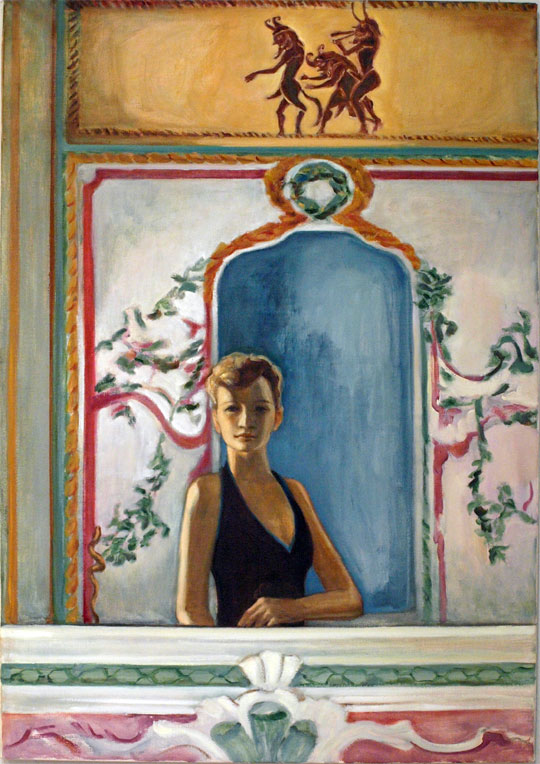

Horses (Boy with Horse, 2007), and snakes (Girls with Snake, 2008) are the representatives of the world of instincts. Zeus is Leda’s abductor as a swan (Swan, 2005), and the Beast (The Beauty and the Beast, 2008) is the frightening embodiment of male sexuality for young girls. In Szépfalvi’s painting Before the Blue (2008), three satyrs (a motif taken from an Athenian black-figure vase) with erect phalli march among the rococo interior’s ornaments, forming the background for a portrait.

Horses (Boy with Horse, 2007), and snakes (Girls with Snake, 2008) are the representatives of the world of instincts. Zeus is Leda’s abductor as a swan (Swan, 2005), and the Beast (The Beauty and the Beast, 2008) is the frightening embodiment of male sexuality for young girls. In Szépfalvi’s painting Before the Blue (2008), three satyrs (a motif taken from an Athenian black-figure vase) with erect phalli march among the rococo interior’s ornaments, forming the background for a portrait.

Violent sexual acts have often been legitimized by traditional art, and this is what Szépfalvi refers to in works such as Faun (2008) and Hunting (2008) where she uses well-known motifs from the history of art. Faun features a Titianesque color composition and its protagonist-Diana, in the position of Christ showing his stigmas-seems to escape from the image, while in the background a Rubenseque Faun prepares to catch a nymph. In the context of Szépfalvi’s show the mask is a motif of concealment and evasion. However, these pictures actually depict preparations for a ball. remont-kvartirspb

Marianne Csáky

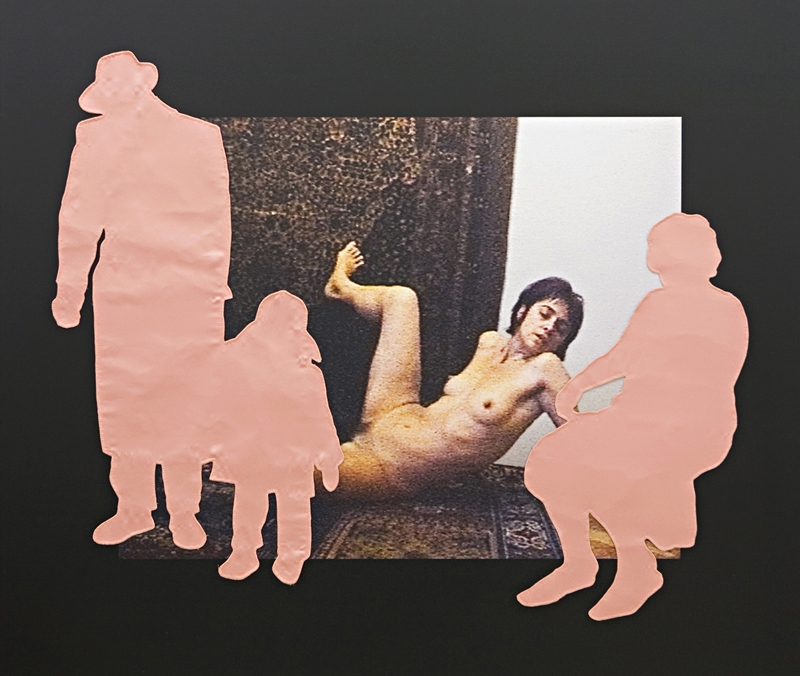

Unlike Nagy, Marianne Csáky is not fleeing from anything. At her exhibition Time Leap No. 2, she dealt with her own life story by inserting her own photographs into photos she inherited from her grandfather. Csáky created a passage from the past to the present by setting up a virtual meeting between people from the past and the present. To her grandfather’s staged photos she applied cut-out silk silhouettes, covered parts of the scenes and creates an ambience that looked like a conversation between kindred souls. The basis of Csáky’s video stills is the present-day adult woman-the artist herself-who appears in explicit sexual positions. Csáky sewed the pink silk silhouettes of figures from the past onto these images, the shadows of men or women with children.

In Csáky’s series, the complexity of identity, memories and sexual desires, as well as the body and its image are interwoven with different temporal dimensions. Her family’s past, and the reconstruction of the past in general, have a distinctive place in her work since any reconstruction of the past is actually a construction. The past leaves only fragments that we put together in order to construct a meaningful whole. We then fill in the gaps between these fragments with our current frame of mind, forming our own future image.

Ágnes Eperjesi

At her show, entitled There is always going to be some more dirty laundry, Eperjesi set out from this eternal truth that governs the lives of all housewives. Unlike the artists I mentioned above Eperjesi’s does not focus her attention on herself. Rather, she carries out chromatic experiments with the methods of a scientist, using the protocols of objectivity. Eperjesi immerses herself in a praxis that even the likes of Newton, Goethe or Oswald couldn’t have imagined, making visible women’s work that was previously confined to hidden places such as outhouses. She has also elaborated a theory of colors for professional laundry workers and non-professional housekeepers. While Eperjesi plays with chromatic evidence she also settles once and for all the romanticized image of washing: “and the kneaded clothes, rustling brightly, / Were twisting and billowing up lightly.”(Quote from Hungarian poet Attila József’s poem Mama (1934). [Original translation by Vernon Watkins in Attila József, Poems (London: Danubia Book Co., 1966).])

At her show, entitled There is always going to be some more dirty laundry, Eperjesi set out from this eternal truth that governs the lives of all housewives. Unlike the artists I mentioned above Eperjesi’s does not focus her attention on herself. Rather, she carries out chromatic experiments with the methods of a scientist, using the protocols of objectivity. Eperjesi immerses herself in a praxis that even the likes of Newton, Goethe or Oswald couldn’t have imagined, making visible women’s work that was previously confined to hidden places such as outhouses. She has also elaborated a theory of colors for professional laundry workers and non-professional housekeepers. While Eperjesi plays with chromatic evidence she also settles once and for all the romanticized image of washing: “and the kneaded clothes, rustling brightly, / Were twisting and billowing up lightly.”(Quote from Hungarian poet Attila József’s poem Mama (1934). [Original translation by Vernon Watkins in Attila József, Poems (London: Danubia Book Co., 1966).])

Eperjesi’s videos and photos are a synthesis of the theory of colors and domestic science. They spiritualize the body and the abject, and they subvert the sublime. The artist’s feminist criticism is subtly ironic. She plays the role of a domestic housewife and elevates domestic work to art. “Those that blend do not mix” reads the text under schematic images of piles of colored shirts waiting to be washed-an ironic commonplace camouflaged as a scientific statement. Nevertheless, the key work of the exhibition was an interactive installation entitled The Color-Neutralizing Washing Machine, an instrument for color processing rather than a tool for washing. When the visitor opens the machine’s glass door she breaks the magic of eternal return by bringing the two colorful circular inscriptions on the machine to overlap (“There is always going to be some more dirty laundry”), then the complementary colors will neutralize each other. At that point the eternal cycle of dirty laundry will have been magically broken.

Eperjesi’s videos and photos are a synthesis of the theory of colors and domestic science. They spiritualize the body and the abject, and they subvert the sublime. The artist’s feminist criticism is subtly ironic. She plays the role of a domestic housewife and elevates domestic work to art. “Those that blend do not mix” reads the text under schematic images of piles of colored shirts waiting to be washed-an ironic commonplace camouflaged as a scientific statement. Nevertheless, the key work of the exhibition was an interactive installation entitled The Color-Neutralizing Washing Machine, an instrument for color processing rather than a tool for washing. When the visitor opens the machine’s glass door she breaks the magic of eternal return by bringing the two colorful circular inscriptions on the machine to overlap (“There is always going to be some more dirty laundry”), then the complementary colors will neutralize each other. At that point the eternal cycle of dirty laundry will have been magically broken.