Doing the Balkans with No Baedeker: Kusturica, Peter Handke, and Beyond

In January 1996, Austrian playwright Peter Handke published his diaries from a recent visit to Serbia, an event that opened him to the widespread excoriating criticism that became known as the “Handke Affair.” As Serbia advanced on Kosovo and NATO made sorties of its own into Belgrade in 1999, the state became increasingly isolated,Slobodan Miloševi?’s rhetoric increasingly inflammatory and nationalistic. Miloševi?’s incarceration and trial at the International Court of Justice at the Hague, the prosecutions of perpetrators of the massacre of Bosniak civilians in Srebrenica and Serbia’s continued objection to Kosovo’s independence in 2008 served only to vindicate Handke’s critics and keep the affair alive. It continues, unabated.This essay takes Handke’s journey as a particular mode of observational writing and a way across the Serbian border. It takes a number of cinematic explorations into the region by Balkan filmmakers keen to write their own terrain and compares their approaches to his. The paper explores in particular a certain phenomenology of the Balkans as motivated by war and the extent to which its observers are caught in its contradictions—by means of their own reflexivity.

In his Room With a View, E.M Forster held out Baedeker’s tour guide as a symptom of a voyeuristic and distanced perspective, offering little in the way of edification much less gratification, even in a country so close to England as Italy: “I hope we shall soon emancipate you from Baedeker. He does but touch the surface of things. As to the true Italy—he does not even dream of it. The true Italy is only to be found by patient observation.”(E.M. Forster, Room With a View (London: Pengiun Books, 2001), 15.)

As winter was closing in on 1995, renowned Austrian writer Peter Handke ventured to Serbia to find something of the remaining heartland of the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. He’d known this place in the way a visiting and lauded writer would—vaguely, translated by local artists and the romantic distortions of memory and, perhaps, the similarly romantic stirrings of his own blood. He is, after all, half-jugoslawisch, his mother a Slovene.

Struck by the prevalently anti-Serbian positions peddled by the major international press and the extent to which these were so uncritically digested even by his own generation of intellectuals, Handke resolved on this wintry trip. Begun just as the Dayton peace conference that would bring an official end to the war in Bosnia was getting under way, his aim was to seek the slippery truth of the matter for himself. His ostensible aim was a retour, precisely because of the war and the new frontiers that now forged its distorted and perverted identity and, importantly for him, to see it from inside. Over two weekends in January 1996, the ink barely dry on the Dayton Accord, his journal was published in the Süddeutsche Zeitung.(“Gerechtigkeit für Serbien. Eine winterliche Reise zu den Flüssen Donau, Save, Morawa und Drina.” Süddeutsche Zeitung, 5–6 and 13–14 January 1996. In the first pressing of this article as a book, its title was inverted—perhaps, one can only conjecture, to avoid its premise and to ease its potential new audience into the land of the Southern Slavs. Eine winterliche Reise zu den Flüssen Donau, Save, Morawa und Drina oder Gerechtigkeit für Serbien (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1996.) Its English title, A Journey to the Rivers: Justice for Serbia, trans. Scott Abbott (New York: Viking, 1997) likely serves a similar purpose.)

A confection of political rumination, of a sort of confabulatory interior dialogue and neatly crafted spleen, his journal takes particular aim at the ‘editorial corps’ and several scribes at the “European desk” (Le Monde, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Der Spiegel), the self-appointed nouveaux philosophes Finkielkraut, Glucksmann and Lévy (just some of the increasing numbers ofpreening contemporary philosophers, he rightly argues, who are ‘everywhere and nowhere’) and a foreign readership unwilling to believe that there just might be more to this than met the eye. His polemic is dressed in a simultaneously sparse and dense personal poetics of a travelogue while it sets its true exculpatory course.

For Handke (seemingly pretty much alone in this view, then as now), the country of his memories had been perverted not just by four years of war but by a certain onanistic writing and media coverage in the West that had cast his friends as a kind of “people of Cain.” But while Handke wanted to see with his own eyes this apparently axiomatic streak of Serbian aggression—he traverses the country with two local comrades, cursorily taking in the sights, peppering his critical and political apperception with the inane observations of a tourist—his poetic meanderings offer little other than a short, sharp critique of some execrable (particularly French) writing and intellectual positioning and a short tract on the artist’s own wounded, subjective terroir. For that alone, this stands as an interesting historical document but the important point of Handke’s piece is that it adverts to (at least the beginnings) of a search, as Walker Percy would have had it.

Handke’s sortie is reminiscent of the cognitive adventure mapped by existential phenomenology. He mobilizes the explorative nature of narrative to unearth the workings of apperception, the very mechanism by which human subjectivity might come to a reflexive space; tempering what might be one’s real sense of self, of place. He comes close to Percy’s notion of the search, “what anyone would undertake if he were not sunk in the everydayness of his own life.”(Walker Percy, The Moviegoer (New York: Avon, 1980), 13.) Percy’s own exploration of the vagaries of reflexivity is more than germane; his protagonist Binx Bolling is painfully aware of his lot, and that of everyone else, dodging (to a point) the reflexive lures of consciousness as he sees them trapping all about him. He is avowedly a seeker, a crafty observer who mines the ideological interstices of the modern and is none too keen on what he sees. He sees in the very reflective apparatus of the cinema and its larger than life culture a capacity to tease out this ideological movement and capture, to seize on the affective faculties that are at once liberating and incapacitating.

Percy argued that the movies were well onto the search but that they “screw it up;” with all their reflexive machinery, they failed to deliver their fellow from the jaws of desperation. In fact, the cinematic machine went even further, delivering him up to a normative little neighborhood, married him off to the local librarian and a mean little suburban patch in which “he was so sunk in his everydayness that he might just as well be dead.”(Percy., 13.) But the movies are his leitmotif, their hapless phenomenology the only apparent mechanism to give life to his reflexive musings … for the moment, anyway.

Yet while Handke embarks on something of a search, like much of the writing and coverage of the region, he fails precisely to poke around sufficient to find anything other than another merely fetishistic Weltenschauung. He misses the trick and, for Percy, this can only end in despair. Notably, Handke begins his journey girded by a viewing of Emir Kusturica’s Underground (1995). He opens his travelogue with ruminations on the sophisticated tableau presented by Kusturica, seemingly a fellow traveler for the cause of a truly adumbrational viewing of the conflicted region. He offers faint praise for Kusturica’s early work (“eye-stuffing fantastification” he avers) but with Underground he found himself moved by the film’s sheer “narrative force” brought about by its connection of the fantastic with a “concrete piece of world and history.”

Yet while Handke embarks on something of a search, like much of the writing and coverage of the region, he fails precisely to poke around sufficient to find anything other than another merely fetishistic Weltenschauung. He misses the trick and, for Percy, this can only end in despair. Notably, Handke begins his journey girded by a viewing of Emir Kusturica’s Underground (1995). He opens his travelogue with ruminations on the sophisticated tableau presented by Kusturica, seemingly a fellow traveler for the cause of a truly adumbrational viewing of the conflicted region. He offers faint praise for Kusturica’s early work (“eye-stuffing fantastification” he avers) but with Underground he found himself moved by the film’s sheer “narrative force” brought about by its connection of the fantastic with a “concrete piece of world and history.”

Handke doubtless takes solace in the fact that Kusturica too was (and continues to be) excoriated by his critics. Despite winning the Palme d’Or in 1995, Underground was virtually boycotted by French audiences due to its portrayal in the French press as pro-Serbian propaganda (Finkielkraut accuses Kusturica of artless imposture here; Glucksmann, with splenetic irony, gladhands him for showing the Serbs as the terrorists they truly were there, etc.). The Serbs did not like it much either, criticising it to the extent Kusturica, at the time, vowed never to make another film. Another interested critic accused the Cannes jury of “indulging in friendly amnesia” as they “agreed to overlook … the film’s origins.”(Dina Iordanova, “Conceptualizing the Balkans in Film,” Slavic Review 55 (4) 9 (Winter 1996), 885.) A European co-production (France, Germany, Hungary and Yugoslavia), the film was apparently sullied by a contribution from Radio Television of Serbia (RTS) which, as the Serbian public broadcaster, was under the control Miloševi?!

Handke doubtless takes solace in the fact that Kusturica too was (and continues to be) excoriated by his critics. Despite winning the Palme d’Or in 1995, Underground was virtually boycotted by French audiences due to its portrayal in the French press as pro-Serbian propaganda (Finkielkraut accuses Kusturica of artless imposture here; Glucksmann, with splenetic irony, gladhands him for showing the Serbs as the terrorists they truly were there, etc.). The Serbs did not like it much either, criticising it to the extent Kusturica, at the time, vowed never to make another film. Another interested critic accused the Cannes jury of “indulging in friendly amnesia” as they “agreed to overlook … the film’s origins.”(Dina Iordanova, “Conceptualizing the Balkans in Film,” Slavic Review 55 (4) 9 (Winter 1996), 885.) A European co-production (France, Germany, Hungary and Yugoslavia), the film was apparently sullied by a contribution from Radio Television of Serbia (RTS) which, as the Serbian public broadcaster, was under the control Miloševi?!

Controversy aside, Underground was indeed onto the search in a manner not achieved by Handke. Where Handke approaches the region in the manner of a saunterer, his ambling pretext undermining his very project, obfuscating his real ideological incision, Kusturica approaches his land as a crazy expedition, like Herzog’s Aguirre or Fitzcarraldo. Underground ventures into the ideological terrain merely picked at by Handke.

As the film opens, a maniacal Gypsy orchestral troupe accompanies, on foot, its two horse-drawn and drunken protagonists Marko and Blacky into the Belgrade of 1941. The raucous pair are hustlers and fearless street brawlers as well as newly joined-up Party members and the war represents for them a delectable opportunity … to fight, fuck and live as large as their intoxicating and breathless antics foreshadow. When the shelling begins in Belgrade the next morning, the two entrepreneurial communists join the fight to protect their country from the Germans and “fascist motherfuckers” everywhere. (It’s already easy to see the appeal for Handke.) They steal weapons and anything they can lay their hands on from the Nazis and as the heat’s turned up on their activities, the two go underground, manufacturing weapons in a deep cellar and a network of tunnels. As the war ends, the unscrupulous Marko has contrived—both through his connections to the Party and his knack for turning a black-market dinar—to fool his old comrade Blacky into believing the war continues.

The Gypsy orchestra continues its live accompaniment to fifty years of Yugoslavian history, more or less accurately sketched for such a vast, distorted and less than accommodating canvas. The “underground” of the title might have been drawn by a loud, hysterical and perverted Dante, an epic poem of Balkan history—Handke sees “Shakespearean force shot through with the power of the Marx Brothers”—but by the time the descending infernal circles are counted, Kusturica has already dispensed with them. Underground refuses such simplicities, at the very same time portraying them in a comical, hysterical and perverted way. While Kusturica plays on nostalgia (the root stock of all narrative but none more than the patriotic history mobilized and manipulated in this particular milieu), he works at a certain realism, depicting too the illusory particles of the heroic past of a now fractured country. It is the latter that displays, to relative degrees, a complexity of view on the conflict and its provenance and that polarises audiences.

What might be seen in its narrative drive is the playing out of the Hegelian struggle to the death between two apparently opposing but intimate forces—Marko and Blacky serve the reflexive core of this grand narrative, which disappears on its announcement, its negation already implicit. Marko and Blacky (same and other) are set to consume each other in the manner of the grand historical narrative that both defines and, as their history will show, erases them. Any opposition to this play is at once annulled and accommodated, recovered in a new guise. This dialectical manoeuvre shows that any notion of a totalising history, of a truly monumental narrative, is false; that history, including the Balkan narrative, is as manifold and multivious as the ideologies that harbour it. This is Kusturica’s clever gambit. As Blacky emerges from his generation of struggle with Marko—apparently the victor, the slave loosed from his master; Marko and Blacky’s cheating wife Natalija immolated on a wheel chair, circling a fallen Christian statue—he is condemned to continue the struggle, taking on all comers: Croatian Ustashe, Serbian Chetniks and the UNPROFOR, all to the familiar refrain “fucking fascist motherfuckers!”

At its conclusion, a rejuvenated cast gather on the Danube for a wedding, replete with orchestra, at the end of a narrative that can only end in a fantasy … that begins again. Blacky sits with his family before spying a furtive Marko, entreating Blacky to let them enter the festivities. Blacky shrugs off his misgivings and invites them in. “My friend,” Blacky announces as they join the boisterous party. Marko asks for forgiveness to which Blacky, perhaps speaking for a lost nation, replies: “I can forgive but I cannot forget.” That’s enough for a jubilant Marko. The party swirls and a piece of the bank breaks away and drifts off with the flow of the river: “Once upon a time there was a country.”

And this too is the point for Handke—his sojourn aims to discover in the “Balkan topography” the repressive kernel of ideology, both as it is lived and acted out by its countrymen but, more importantly, how the conflicts and their globalized projections have been distorted and overdetermined by a merely lickerish media and its all-too-interested correspondents. This is Handke’s search but it unwittingly goes further as it implicates him in the same process of overdetermination—his own reflexive apparatus is distorted, himself a little too interested for any good to come of it. Percy’s distinction was precisely his distance, his capacity to observe the reflexive and ideological processes at play by not getting in the game.

It wasn’t only the French that didn’t warm to Underground or Kusturica or, for that matter, Handke. The Slovene Žižek argued Kusturica simply served up a messy plate of pornography for a perverted Western gaze. In fact, Žižek appears to cite any reading of the conflicts in the Balkans(especially Western readings of its war or post-war politics but Kusturica’s is, for him, as bad as any) as just another perverse and fetishistic brick in the wall of Balkanism—another Balkan frame onto which the West could project its own “phantasmic content.” He argues that instead of “trying to understand” the foreign reader should practice a sort of “inverted phenomenological reduction … resist the temptation to understand” and, indeed, that their unwelcome gaze should be averted.(Slavoj Žižek, The Plague of Fantasies (London: Verso, 1997), 62.) So much for the promised fortunes of adumbrational viewing…

But such projections are not the sole domain of the Western voyeur, as Bosnian director Danis Tanovi?’s No Man’s Land (2001) wryly observes. In this film two Bosnians and a Serb are caught in a kind of ‘Balkan stand-off’ in a trench between enemy lines, a Serbian soldier, on watch over this eponymous terrain and the confusion in its midst, seems more interested in the pages of a tattered magazine he clutches like some shared piece of porn. He moans in disgust, before sharing the gruesome details with his comrade: “You should see the mess in Rwanda!” Srdjan Dragojevi?’s Pretty Village, Pretty Flame (1996) took his characterizations of the conflict down a path similar to the allegorical one confected by Kusturica. As a young Serb Milan is recovering from his wounds in a hospital bed, recalling the events that delivered him there, including his erstwhile friendship with the Muslim Halil. As the war descended on Bosnia, Milan joined the Bosnian Serb Army and soon found himself in retreat, besieged by Bosniak soldiers in a tunnel—the abandoned Tunnel of Brotherhood and Unity! While too accused of propounding a pro-Serbian thesis, Dragojevi? personifies the conflict in the reflexive duumvirate of Serb Milan and Bosniak Halil, once boyhood friends growing up in a somewhat more bucolic space, pre-war, by this abandoned tunnel.

But such projections are not the sole domain of the Western voyeur, as Bosnian director Danis Tanovi?’s No Man’s Land (2001) wryly observes. In this film two Bosnians and a Serb are caught in a kind of ‘Balkan stand-off’ in a trench between enemy lines, a Serbian soldier, on watch over this eponymous terrain and the confusion in its midst, seems more interested in the pages of a tattered magazine he clutches like some shared piece of porn. He moans in disgust, before sharing the gruesome details with his comrade: “You should see the mess in Rwanda!” Srdjan Dragojevi?’s Pretty Village, Pretty Flame (1996) took his characterizations of the conflict down a path similar to the allegorical one confected by Kusturica. As a young Serb Milan is recovering from his wounds in a hospital bed, recalling the events that delivered him there, including his erstwhile friendship with the Muslim Halil. As the war descended on Bosnia, Milan joined the Bosnian Serb Army and soon found himself in retreat, besieged by Bosniak soldiers in a tunnel—the abandoned Tunnel of Brotherhood and Unity! While too accused of propounding a pro-Serbian thesis, Dragojevi? personifies the conflict in the reflexive duumvirate of Serb Milan and Bosniak Halil, once boyhood friends growing up in a somewhat more bucolic space, pre-war, by this abandoned tunnel.

As boys they were fascinated by the tunnel but feared some folkloric ogre (perhaps the ghost of Tito) lurking in this unfinished major public works project like some Minotaur. Žižek has no trouble finding monsters in Dragojevi?’s spiel too. While Pretty Village, Pretty Flame uses flashbacks to pre-war life and times in Yugoslavia, the ten-day siege itself is presented from a Serbian perspective, the Muslim forces are represented merely by echoing voices and cat-calls hectoring the Serbs. Žižek attributes to these disembodied voices the “all-powerful spectral dimension” of those whisperings and shadows lurking in horror films “and even Westerns, in which a group of sympathetic characters is encircled by an invisible Enemy …”(Slavoj Žižek, Welcome to the Desert of the Real! (London: Verso, 2002), 39.)

Thus, according to the Slovene, this narrative device of the circled wagons personifies the Serb, turning the table on the real state of the Bosnian siege, allowing our appreciation and identification with their plight while the surrounding Muslims remain disembodied threats to our own subject position. According to Žižek this is reinforced by some apparent subterfuge—while in the interests of either balance or realism, Serb forces are shown in the beginning of the film raping and pillaging, it is not theseSerbs, “these soldiers,” he argues, “mysteriously just pass through burnt-out villages—no killing seems to take place, no one seems to die … This properly fetishistic split (although we, the spectators, know very well that these soldiers must have done their share of killing Muslim civilians, we are not shown this, so we can continue to believe that their hands are not full of blood) creates the conditions for our sympathetic identification with them.”(Žižek, Welcome to the Desert of the Real!, 39.)

Handke similarly pointed to the circled wagons, this time in defence of the Bosnian Serbs. Likening the geography of the siege of Sarajevo to that portrayed in the genre of the Hollywood western, with the “bad Indians” scurrying over rocky crags above apparently laying siege and waste to the settlers in the valley below. Handke here argues, despite their apparent upper hand, it is the siege layers who are in fact the “freedom fighters,” that those in the valley below, while gaining our sympathies as victims and thus fitting the narratalogical frame of a good Hollywood western, are the real colonisers of the land of the Southern Slavs.(Peter Handke, Sommerlicher Nachtrag zu einer winterlichen Reise (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1998), 249.) It is precisely the perversity of this situation that is in Handke’s sights. Accusing the half-Slovenian Handke of some fetishistic interpassivity as he sided with the Serbian cause, Žižek, as if in defence of his own authenticity as a new European, seems beside himself: “No wonder, then, that he has turned to Serbia as the last vestige of authentic Europe, comparing Bosnian Serbs laying siege to Sarajevo with Native Americans laying siege to the camp of white colonizers ….”(Žižek, The Plague of Fantasies, 126-30; see also, Žižek, Welcome to the Desert of the Real!, 39.)

But this polemic goes back a little further than ruminations on the conflicts set at the split of the Yugoslav Federation. While Yugoslavia was still intact (if, in some minds, a mere construct), Croatian director Lordan Zafranovi?’s Occupation in 26 Pictures (1978) took to the ideological divisions and latent tendencies in the region using the Axis-bestowed Croatian state of 1941 as his frame. Centred on the relationship of three close friends—portentously the ethnic troika of a Croat, a Jew and an Italian—living an “unideological” but hedonistic life in Dubrovnik, seemingly unfettered by nationalist or religious positionality until war enters their realm.

But this polemic goes back a little further than ruminations on the conflicts set at the split of the Yugoslav Federation. While Yugoslavia was still intact (if, in some minds, a mere construct), Croatian director Lordan Zafranovi?’s Occupation in 26 Pictures (1978) took to the ideological divisions and latent tendencies in the region using the Axis-bestowed Croatian state of 1941 as his frame. Centred on the relationship of three close friends—portentously the ethnic troika of a Croat, a Jew and an Italian—living an “unideological” but hedonistic life in Dubrovnik, seemingly unfettered by nationalist or religious positionality until war enters their realm.

The film is a sophisticated and brutal depiction of fascist onslaught and collaboration. While suitably savage on the Nazis and the fascist puppet Paveli?’s Ustasha, its theme is the rude affect of fascism on loosely held conviction and the extent to which ideology is merely labile. Cowardice, lust and tribal affiliation soon descend into a bloody and orgiastic Hell. The interstices of these relations and their investigation are at the core of the search Percy urged us to undertake. Only an exploration, at least a sortie into this realm can deliver us to their possibilities, alert us to their dangers, but one must be careful not to get caught in its contradictions.

Occupation in 26 Pictures with a Nazi scout on a motorcycle entering the empty city square, coming to a halt on the cobbled streets. The rider dismounts and, with Leica in hand, begins the occupation of thetitle—the pictures that follow are, by and large, of horrors perpetrated by nationalist Croats themselves, rather than their puppeteers. Here, plenty of attributable killing takes place—mostly by “fucking fascist mothers,” as Kusturica’s Blacky would have it, but certainly by some defensive partisans. One wonders at what the New European’s view of this political set up might have been. The film shares much with its European contemporaries—a particular Freudo-Marxist or Reichian turn on fascist latencies that seemed illuminated by the war, Zafranovi?’s Occupation was in good company with the likes of Cavani, Pasolini, Wertmuller, Visconti, de Sica, Bertolucci, Jancsó and, of course, his countryman Makaveyev.

The narratives of these post WWII filmmakers venture into the ideological nether land of war but their symptomatic reading points sedulously to the workings of ideology itself, war proving just a timely motif for the narratives across which it operates. They were, indeed, onto the search …While Kusturica and Handke operate in this terrain too, they come at a time when analyses of their work are nearly as overdetermined as the subjects they explore.

This overdeterimation—ideological, filmic and theoretical—can be seen in the Greek Theo Angelopoulos who embarked on his search the same year as Kusturica, turning out the critically acclaimed Ulysses’ Gaze (1995). All the narrative ingredients for a real voyage of discovery are there as Angelopoulos ruminates on the theme of loss, homeland, culture, and the quest one undertakes in the interstices of states, personae and relationships as they are played out across the Balkan conflict. While his film may be something of a poetic elegy to the stateless urges of the exile its real theme is muted by the very poetry it mobilizes.

This overdeterimation—ideological, filmic and theoretical—can be seen in the Greek Theo Angelopoulos who embarked on his search the same year as Kusturica, turning out the critically acclaimed Ulysses’ Gaze (1995). All the narrative ingredients for a real voyage of discovery are there as Angelopoulos ruminates on the theme of loss, homeland, culture, and the quest one undertakes in the interstices of states, personae and relationships as they are played out across the Balkan conflict. While his film may be something of a poetic elegy to the stateless urges of the exile its real theme is muted by the very poetry it mobilizes.

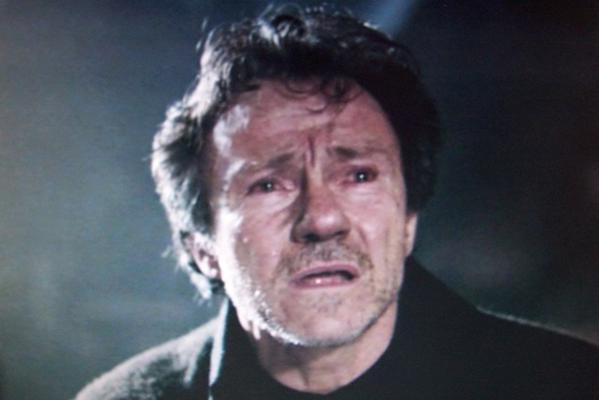

Angelopoulos’s desire to repatriate the Greeks’ filmic gaze on the Balkans takes us back to the possibility of three reels of film produced by the first Balkan filmmakers, the Manakis brothers but since lost, undeveloped even, somewhere in the mire of warring countries to the north. The film opens with its protagonist, an unnamed Greek-American filmmaker (Harvey Keitel)—he is our “Ulysses,” scripted merely as “A”—narrating a piece of scratchy Manakian footage of weavers made in 1905 in their home town of Avdella near the border between Albania and Macedonia: “Weavers. The first film ever made in Greece and the Balkans. But is that a fact?” He ponders the possibility of this lost film: “Was this the first film, the first gaze?”

This modern, filmmaking Ulysses puts himself in the picture and his journey begins, now. Greek-American—a Greek in exile—A returns to his home town of Florina at the invitation of his fans for a screening of one of his controversial films. Cast out of the cinema by apparently religious protesters, the film plays on to a sort of transfixed audience passively watching in the rain, each obscured by an umbrella, the soundtrack sets the scenes to follow: “We’ve crossed the border and we’re still here. How many borders must we cross to reach home?” The filmmaker is greeted by one of his friends along the way: “The first thing God created was the journey,” says friend and journalist Niko, to which our A answers, as if completing the password: “Then came doubt, and nostalgia.” The film is indeed about nostalgia and the filmmaker’s odyssey—at once a sortie and a homecoming (nostos)—is more about him than either the film he seeks or the numerous perspectives encountered in the Balkans he traverses in order to unearth it. In this, his project is akin to Handke’s, if the comparison ends there. As he heads north through ice and fog, he encounters all the predictable borders—the liminal spaces of geography, history, memory—writ large by exile. The languorous takes and minimal dialogue portend more a poetics of exile and the marginal, the landscapes in the mist of Angelopoulos’ earlier and less grandiloquent ode to home, than this grand allegorical cut through Balkan history.

This modern, filmmaking Ulysses puts himself in the picture and his journey begins, now. Greek-American—a Greek in exile—A returns to his home town of Florina at the invitation of his fans for a screening of one of his controversial films. Cast out of the cinema by apparently religious protesters, the film plays on to a sort of transfixed audience passively watching in the rain, each obscured by an umbrella, the soundtrack sets the scenes to follow: “We’ve crossed the border and we’re still here. How many borders must we cross to reach home?” The filmmaker is greeted by one of his friends along the way: “The first thing God created was the journey,” says friend and journalist Niko, to which our A answers, as if completing the password: “Then came doubt, and nostalgia.” The film is indeed about nostalgia and the filmmaker’s odyssey—at once a sortie and a homecoming (nostos)—is more about him than either the film he seeks or the numerous perspectives encountered in the Balkans he traverses in order to unearth it. In this, his project is akin to Handke’s, if the comparison ends there. As he heads north through ice and fog, he encounters all the predictable borders—the liminal spaces of geography, history, memory—writ large by exile. The languorous takes and minimal dialogue portend more a poetics of exile and the marginal, the landscapes in the mist of Angelopoulos’ earlier and less grandiloquent ode to home, than this grand allegorical cut through Balkan history.

The three reels of the quest already set the bounds of this narrative. The journey, the search is contained, if lost, in a feature-length film—a beginning, a middle and an end—in which seemingly innumerable borders will however be transgressed. By way of various crossings—that take him inter alia to a film archive in Skopje, an elaborate interactive flashback in Bucharest, and a visit to the former head of the Film Archive in Belgrade—he finds his three reels, placed in the care of Levy, an old Jewish archivist, a cineaste working in a bombed out cinema in Sarajevo at the height of the siege.

For years, his curator has even been working on a special chemical formula to unlock this first Balkan gaze and it miraculously comes together as A ventures to the city. But there is, of course, a price to be paid. The traveller makes friends, none more than the friendly old Levy and his family who greet him as their own. As the lost images emerge from Levy’s alchemy a fog descends. “In this city the fog is man’s best friend,” say the old man. “The only time the city gets back to normal, almost like it used to be. The snipers have little visibility. Foggy days are festive day here so let’s celebrate! Besides, we have another cause for celebration: a film. A ‘captive gaze’ from the early days of the century, set free at last, at the end of the century. Isn’t that an important event?” The old cineaste leads Ulysses out into the street where a youth orchestra plays strings. They will walk in the fog by the river with his family. Of course, this can’t end well. As the family spreads out along the road they disappear into the fog and are rounded up by (the “spectral voices”) of enemy soldiers; the old man runs ahead to intervene and all, but the filmmaker, are gunned down and killed as A stares into the mist.

The fog motif is noteworthy and somewhat akin to an ethnic inversion of what Žižek put forward above “in which a group of sympathetic characters is encircled by an invisible Enemy …” It is the fog, creating a dim surreality accompanied by the haunting music of civilization as it disappears behind its familial subjects, that establishes the heretofore unrepresented enemy as the monsters of the piece. “Children first!” they demand in this perverse Transylvania where Vlad Dracul rules. Tomaslav Longinovi? argued this point: “The global media would have us believe that the Balkans are inhabited by Dracula’s kin, while the inheritors of Mitteleuropa are the diligent descendents of Roman Catholic civilization …. The victimizer draws strength from past suffering, assuming a predatory role in order to avenge age-old injustices.”(Tomaslav Longinavi?, “Vampires Like Us: Gothic Imagery and ‘the serbs’” in Dušan I. Bjelić, and Obrad Savi? Eds. Balkan as Metaphor: Between Globalization and Fragmentation (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2005), 41–2.)

This outcome is intimated earlier as A enters Belgrade and, on a tram with his friend the Greek war correspondent, is asked: “What are you looking for? Signs of war? You won’t find any. The war’s so close that it might as well be far away.” Belgrade is austere but relatively unblemished in this film. As the traveller enters Sarajevo, we are subjected to slow, panning images of its almost total devastation and privation, truly reminiscent of scenes from the Holocaust. This is affirmed by the presence of a youth orchestra—made up of Serbs, Croats and Muslims—who come out to play during cease-fires, going from place to place lifting the spirits of the locals (the signature lament by Eleni Karaindrou, the soundtrack to the entire film).

The devastated A wanders back through the fog-bound crowd. We come to him now as he sits in his old friend’s theatre, having just seen the images of his quest. He can barely contain his grief as he mouths the mournful apologue of his progenitor: “When I return, it will be with another man’s clothes …. I will tell you about the journey …. The story that never ends.” It is no coincidence there was little political flack for Angelopoulos over the film—he pushes enough clichéd buttons to ensure the only real criticism his film suffered were suggestions it was a pretentious poeticism of the conflict. While an unabashed “Balkan filmmaker”, his homage to the cinema of “Mitteleuropa”—references to Murnau, Dreyer, Antonioni, the mobilization of Tonino Guerra on script, an on—ensures him safe harbor …

Percy finds the elusory subject of his search, at least for a moment, in the fleeting visage of William Holden as he crosses Royal and turns into Canal in the New Orleans. Angelopoulos finds Harvey Keitel in a cinema in Sarajevo and he cannot help but leave his man in despair—his filmmaker has lived a full, if fractured life and come a long way but any sort of homecoming is, for him, out of the question. The director has shown a country held together by oneiric landscapes, floating ideals and distant memories, all accounted for, in some way, by his Ulysses. His subject transgresses boundaries with relative ease but the plenitude this suggests is mere illusion, his director at the same time depicting a country, a homeland, falling apart at the border. Ulysses’ gaze, his Ithaca, is merely the flickering light of a projector in a bombed out theatre. The Balkan seed is sown again; precisely in the place it is doomed.