Displacement and Identity: Arnold Daghani

The following essay is part of a series devoted to contemporary art and architecture East-Central Europe. It was first delivered as a paper at a conference held at MIT in October, 2001.

What was the experience of an aspiring Modernist artist in Romania in the late 1940s and 1950s? Arnold Daghani (1909-1985) may be a case in point.(This paper represents early research for a project now funded by the Leverhulme Trust, to run from 2001-4 at the University of Sussex, where a large collection of around 6,000 artworks and other documentation by Daghani is held in the Arnold Daghani Collection.) Daghani, who worked in Bucharest between 1944 and 1958, grew up in Suczawa (now Suceava), in the Bukovina, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire—as Paul Celan emphasized, its “easternmost” part.(John Felstiner, Paul Celan: Poet, Survivor, Jew, New Haven & London, 1995, 4.) The dominant language was German until 1918 when the region was annexed by Romania and became part of an expanded nation seeking to discover and establish its new identity.

During the 1930s, Daghani lived mainly in Bucharest, until 1940 when his home was destroyed in an earthquake and he decided to move with his wife Nanino back to the Bukovina—to the capital Czernowitz.

At that time, the Bukovina was under Soviet control and conditions looked more favorable for Jews than in Romanian Fascist—controlled Bucharest. However, shortly after they arrived, the Nazis, together with their Romanian collaborators, occupied the region and began deporting Jews eastward.

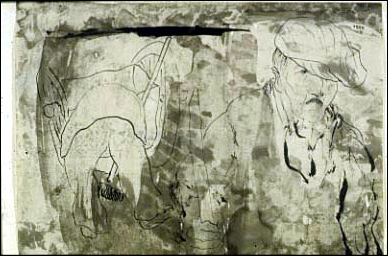

In June 1942, Daghani and Nanino were sent across the river Bug to the forced labor camp at Mikhailowka in southwestern Ukraine where they worked on repairing the main road in the region for a German engineering company, part of the Organization Todt.

In July 1943, while working on an artistic project of an eagle mosaic commissioned by the engineers and with the aid of the local Jewish resistance, Daghani and Nanino escaped and crossed the river Bug back into the relative safety of Romanian—controlled Transnistria.

There they hid in the ghetto in Bershad until located by the Romanian Red Cross and taken back to Bucharest. While in Bershad, they heard how all their remaining fellow inmates had been executed. They arrived in Bucharest in March 1944.

Daghani’s experiences in Mikhailowka continued to have an impact on him for the rest of his life, both emotionally and as manifested in his work. His diary account of the period, The Grave is in the Cherry Orchard, was published in Romania in 1947 and was well received officially, confirming as it did the brutality of Fascism.(Monica Bohm-Duchen, Arnold Daghani, London, 1987, 26.)

However, on an individual level, Daghani experienced rejection and unsympathetic responses from people either wishing to move on and not wanting to hear about wartime experiences or not believing him.

Daghani records how even an educated friend who read his manuscript then told him, “It would be terrible, were it true. Can you spare me a glassful of oil?”(A Large, A Big Question Mark, 1968, unpublished notebook, Arnold Daghani Collection, C39.41r.)

The responses from both family and in artistic circles to his visual works smuggled out of the camps were similarly negative or dismissive.

Daghani wished simply to “depict life in the camp”(The Grave Is in the Cherry Orchard, 1947, London, 1961, 100.) and had made a conscious decision to portray the dignity of the inmates rather than their beatings and executions which “would certainly lower the almost super-human dignity with which the slaves went to the grave . . . why cheapen that by atrocities painted or drawn, even if they surpass imagination and “happen” to be true?”(“Let Me Live,” n.d., manuscript, Arnold Daghani Collection, 63.) However, as a result, the images were perceived as not horrific enough and, therefore, of little value.

While Daghani’s personal memory was haunted by his experiences in Mikhailowka and memories of his fellow inmates, Romania aimed to establish a clear distance between the country as a Nazi ally and a postwar Communist state. Both before and after the war Romania was concerned with its national identity as the country sought to define itself.

These concerns were expressed politically and also geographically; Romania’s involvement in the war had been partly related to territorial issues—the threat from the Soviet Union and the initial belief that Germany would be better able to protect the country’s borders.

National concerns were also manifested culturally and economically. Romania had traditionally kept strong links with the West, particularly with France and Britain, and in prewar southern Romania, the educated spoke French at home. Romanian cultural developments were often influenced by those in Paris, while in the Bukovina, connections with German-speaking culture were important.

As Steven A. Mansbach points out, “Most aspiring young painters and sculptors were encouraged to finish their education in Munich and Paris.”(Steven A. Mansbach, Modern Art in Eastern Europe: From the Baltic to the Balkans, ca. 1890-1939, Cambridge, 1999, 245.) While Daghani did not receive a formal artistic education, he too spent some time in Munich, in the late 1920s, and possibly in Paris where he may have attended drawing classes.(Bohm-Duchen, Arnold Daghani, 11.)

Many of the most influential Romanian artists contributed to significant artistic developments abroad: Tristan Tzara and both Marcel and Georges Janco lent their vision to Zurich-based Dada; Marcel Janco later set up the artistic community at Ein Hod in Israel; Constantin Brâncusi drew on his Romanian background in Paris; and Victor Brauner was involved in French Surrealism.

Others went abroad and returned to Romania including both Ion Jalea, who studied with Bourdelle in Paris, and Max Herman Maxy, who had been involved with the Novembergruppe in Berlin during the early 1920s.

Maxy later returned to become a prominent figure in the Bucharest avant-garde, contributing to journals such as Contimporanul and Integral, and working in a Constructivist-Cubist style.

During the 1920s and 1930s, then, the Romanian cultural scene was lively and progressive, with important developments being made in the visual arts as well as architecture, music, poetry, and literature.(See Luminita Machedon & Ernie Scoffham, Romanian Modernism. The Architecture of Bucharest, 1920-1940, Cambridge, Mass., & London, 1999, for a detailed analysis of this period in Romanian architecture.)

The 1930s were particularly dominated by “the obsession for tradition and for the national specific” throughout Europe as the rise in political nationalism was reflected in the arts toward the aim of manifesting national identity.(The Gallery of Romanian Modern Art, Bucharest, 2001, 137.)

In postwar Romania, with the establishment of the Communist government in 1948, ties were instead directed eastward toward the Soviet Union, which the Romanians had largely resented for its territorial claims and which had recently succeeded in acquiring Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina.

Even the orthography of language was affected in 1953 when Romania became Romînia with a Russian-derived î replacing the Latinate â, until reversed by Ceausescu in 1964.(Katherine Verdery, National Ideology Under Socialism: Identity and Cultural Politics in Ceausescu’s Romania, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1991, 104, 116.)

National identity was again under construction, and the following decades would continue to be a dominant political issue as Ceausescu’s Romania attempted to become an independent Communist country, straining relations with Moscow and forging independent ties outside the Warsaw Bloc. These moves also led to further Romanianization, and prewar intolerance to influences perceived as”foreign” resurfaced.

In 1989, toward the end of the Communist period,the place of Romania in Europe again became foregrounded in discussions of national identity. As Katherine Verdery explains,”To be against the regime had become synonymous with being pro-European, whereas Ceaucescu and those in factions more or less allied with him ranted against western imperialism and the Europeanizing obliteration of the national soul.”(Ibid, 2.)

In the postwar period, then, in line with Moscow’s directive, Socialist Realism was promoted as the way forward. The country needed to build a new society, and as Justice Minister Lucretiu Patrascanu proposed in 1945, the new culture would be “national in form and social in content”—and above all, it would be “progressive.”(Keith Hitchins, Rumania 1866-1947, Oxford, 1994, 526.)

Keith Hitchins notes that Patrascanu “displayed contempt for the inter-war intellectual, whose ‘lack of principles’ and ‘cheap opportunism’ he attributed to the society in which they lived.”(Ibid.) To put it simply, the cultural enemy was now the rebellious Modernist individual, and the time had come to look ahead and build the new Romania together.

In a 1984 state publication, Vasile Florea writes that “artists were recommended . . . to approach only significant subjects concerning social struggle, free work, heroic deeds, all of them having the new man, the positive, exemplary hero in the center. As to the language of art, it had to be simple, accessible to the broadest masses and having no special aesthetic training.”(Vasile Florea, Romanian Art: Modern and Contemporary Ages, Bucharest, 1984, 266.)

A major exhibition, Flacara, took place in April 1948 in the Dalles Hall, Bucharest, in which all 830 works were, Florea writes, “concentrating on the theme of present-day man and his work,” while the exhibition catalogue noted that although there was a “common effort to create a style of progressive realism in Romanian art . . . formalism has not yet been done away with and the remnants of decadent art under all possible forms of its impressionist, expressionist [sic] deviations have been only in part removed.”(Ibid, 268.)

While Daghani’s work was rarely openly critical of the political situation, his refusal to join the Union of Artists and Sculptors until 1957, as well as his rejection of Socialist Realism, meant that he was unable to exhibit officially.(Daghani finally joined in 1957, one year before emigrating “upon the insistence of art critic Petru Comarnescu. . . . I continued, however, to keep myself aloof, nor did I sell anything.” See What a Nice World 1942-77, unpublished album, Arnold Daghani Collection, 176, G1.091r.)

To earn a living, he taught English, while his wife taught French, both languages of places associated with the Romanian cultural past. Works reveal an interest in traditional Romanian folk arts or depict ordinary people in contemporary life.

A 1949 ink drawing shows three disabled soldiers, and Daghani makes an analogy with Pieter Bruegel’s Parable of the Blind which in turn was based on a parable of Christ. In other drawings, Daghani observes street workers—not, however, depicted as Socialist Realist heroes, but with simple dignity. In short stories, he observes everyday life, narrating the interactions between people living close together in cramped apartments.(Examples of stories include Festina Lente (1950), 1963-68, C4, and Our Neighbour in Pierrot Lunaire, 1966, C19.)

Daghani produced a wide range of works including studies of the nude, portraits, and abstract compositions, often characterized by a sensitive use of line akin to Matisse or Picasso with whom he was compared.

Daghani writes of how one day when he was out, “A woman-caller, who had seen my drawings in the nude, offered herself to sit for me in the nude, and would I accept it? Would I? It’s a godsend. Socialist realism highly disapproves of drawings or paintings in the nude.”(A Large, A Big Question Mark, C39.25r.)

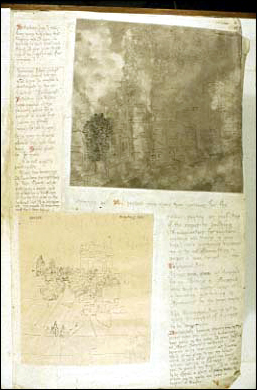

Daghani was always interested in the place in which he lived, and in 1952, while drawing the Triumphal Arch in Bucharest, an act deemed to be illegal since the landmark was considered a “war target,” he reflected upon how he still had to draw in hiding, as in the ghetto at Bershad: “Things have, alas, not changed for me.”(What a Nice World, 150, G1.078r.)

Comments such as these quoted above, selected from Daghani’s extensive writings, perhaps reveal as much about the author as the artistic and political context in which he lived.

Such statements require careful deconstruction to identify the extent of Daghani’s highly subjective interpretation of the situation, as well as his concern for the audience for which his writings, retrospectively and in English, were intended.

Many inscriptions from this period relate to notions of the “Free World,” that other place in which Daghani believed that artists, especially geniuses, succeeded according to the merits of their work, rather than through political or other affiliations.

Daghani’s insecurity as an artist, accentuated by his lack of training, made this notion especially appealing. Furthermore, his rejection of the Socialist Realist collective strengthened the appeal of the Modernist individual artist.

Daghani’s displacement was, therefore, complex and multilayered; he was now working as an artist, but without official recognition, and was still drawing places where he was not supposed to be.

An Anglo/Francophile from a Jewish background who had grown up in the German-speaking Bukovina, he was now living in the Romanian culture of Bucharest. By rejecting Socialist Realism, Daghani confirmed himself as an outsider politically as well.

Religion was very important to Daghani, and through Daniela Miga, with whom he had an affair in the 1950s that lead to a brief divorce from Nanino, he became involved with Eastern Christian Orthodoxy. His works of this period depict priests, monks, and church interiors. He produced five windows for the Good Samaritan Chapel, Bucharest, and in 1958 was invited to exhibit at the Patriarch’s Palace.

Although the church was tolerated by the authorities, by this time Daghani was a member of the Artists’ Union, and he records how artist and critic Oskar Walter Cisek was “adamant” that he should not show there: “No exhibition of Sacred Art. Both the authorities and the Union of Artists and Sculptors, a full member of which I am, would view such a step of mine very unfavorably, he stressed again and again, after an almost two-hour pleading with me in the Street.”(A Large, A Big Question Mark, C39.20r.)

In the end the exhibition took place but “in camera,” just for the Patriarch, archbishops, and bishops, and a few of Daghani’s friends.

Daghani reveals that “at the back of my desire” was “not the show per se” but the possibility that Daniela might see his window “The Ninth Station,” which she was unable to see at his home because she and Nanino, with whom he was now remarried, were not on good terms.(Ibid.)

Daghani’s rather complicated private and religious life—Daniela was Orthodox and Nanino was Jewish—seems to reflect his exploration of his own complicated identity, as he distanced himself from his Jewish background and developed his own independent faith.

Some years later Daghani wondered whether the authorities or the Union would have believed this real reason for the exhibition: “Since I kept myself aloof, refusing to take part in any artistic manifestation, I am branded as a reactionary, and what I really am is a humanist, just putting human interests paramount. Behind the Iron Curtain nothing has to exist but the Party. And I cannot bow to it. Brainwashing has gone on on such a scale that Stef’s cousin kneeling at church for his prayer heard himself say: Tovarish St Nicholas!“(Ibid, C39.21r.)

In June 1944, shortly after his return to Bucharest, Daghani showed Maxy the works he had smuggled out from Mikhailowka. Daghani writes, “He does not think much of my watercolors or of my pencil drawings, but to him I am a ‘dare-devil of the pen and ink.'”(What a Nice World, 134, G1.070r.)

In 1955, Daghani again invited Maxy, now director of State Museum of Art and a very influential figure, to see his work. This time Maxy told him that he was “a great artist” who had “much more to say than all of the exhibiting artists” he had seen on a recent trip to Paris.

Maxy then asked, “Why, for heaven’s sake, are you stubborn to go on teaching English, instead of having the position in art you deserve? You prove by your work in front of me that you can handle every manner; why not also in the socialist realistic way?”(Ibid, 154, G1.080r.)

Maxy seems to have encouraged Daghani to be pragmatic in order to establish a better life for himself, an arrangement that seems to indicate the complex situation in which artists such as Maxy were in prominent positions.

Although Daghani could not achieve public recognition, during the 1950s he appears to have built up a large circle of admirers, and a visitors’ book is filled with the signatures of those who came to see him.

From 1957 through the end of November 1958 he records 302 people of various professional backgrounds making at least their first visit. Detailed accounts are given of some of these meetings with the most influential figures of the time.

Daghani records how some friends, on their way home late one evening, met Ionescu from the Institute of Fine Arts, who tried to guess where they had been: “From your glittering eyes I dare guessing where you have been: At Daghani’s. I’d like very much to go and see his work myself.”(Ibid, 160, G1.083r.) Daghani was duly flattered. Daghani also quotes how he was described as a “great genius,”(Quoted in letter to Carola Giedion-Welcker, 17 October 1976, Jona, translated in Memoirs Switzerland, c. 1946-1979, Arnold Daghani Collection, C21.059r.) “the greatest artist”(Ibid.) and “the only serious artist in the country.”(A Large, A Big Question Mark, C39.27r.)

Despite or perhaps due to his stance in opposition to Socialist Realism, people seemed to be really interested in his work, including those in official positions. In the late 1950s, Aurel Diaconu of the Society for Cultural Relations with Abroad, Publications Division, suggested that Daghani should become a contributor as an artist.

Daghani was surprised: “‘Don’t you know that I . . . well, that I’m not toeing the Party-line, and do not work Socialist-Realism?’ I asked. ‘Of course we do,’ he answered. ‘It is for that reason,’ he continued immediately, ‘that I have contacted you. We want you as a contributor to the publications that are sent abroad.’ I declined it.”(Ibid, C39.26r.)

As Daghani wrote, “Here where everybody except myself has been toeing the party line, I may just be the one-eyed among the blind.”(What a Nice World, 162, G1.084r.) The authorities too, then, in starting to seek closer relations with the West, began to welcome greater artistic diversity.

In 1958, Daghani and Nanino emigrated to Israel, although it was not Daghani’s ideal destiny (“I was not keen on leaving for Israel, that for purely personal reasons.”(A Large, A Big Question Mark, C39.65r.)). Before leaving, they heard how fellow Romanian artist Vilma Badian was not happy there and particularly disliked the “co-operative basis and everything” of the Ein Hod community.(Ibid, C39.35r.)

Daghani writes: “In addition to this discouraging news there is my constant fear of meeting with failure. Although I have been forced to keep myself aloof . . . the moral support tendered to me by critics, art-lovers, and the Artists’ Union, makes me feel like in a fold; once abroad, I am afraid, I shall have that feeling of protection no longer.”(Ibid, C39.35r-36r.)

A consistent admirer of Daghani’s work was the highly respected art critic Petru Comarnescu, member of the Criterion avant-garde intellectual group in the mid-1930s, who wrote of Daghani’s work that “the output is immense, the diversity bewildering,” and he praised the “mastery” of each style: “Daghani is a superb draughtsman and one of the most profoundly thinking artists of our times.”(Extract from article by Petru Comarnescu in Memoirs Switzerland, C21.025v.)

Letters written during the 1960s to Daghani, then living in Vence, indicate the difficulties he was now facing as an artist in the “Free World.” In January 1963, Comarnescu wrote: “I expect to learn that you had the glorious exhibition you deserve. . . . It is not possible that an artist like you should not be known and appreciated on a large scale. . . . The line of Arnold Daghani is to me of the same sensibility, finesse and force as the line of the best drawings of Picasso.”(Letter from Petru Comarnescu, 17 January 1963, Bucharest, copied out in Memoirs Switzerland, C21.059r.)

However, by September 1964, when Daghani’s career was still not going well, and he was still was not meeting “the people able to understand the outstanding and great personality of Arnold Daghani,” Comarnescu wrote that “I thought of suggesting to you to come back to Romania where you would be among the first and highest artists.”(Letter from Petru Comarnescu, 30 September 1964, Bucharest, copied out in What a Nice World, G1.084r and in Memoirs Switzerland, C21.033v.) But this was not possible, and thoughts of the contrast between his distance from the art world of Vence and potential recognition in Romania heightened his sense of despair and isolation.

Following years of disappointment in the “Free World,” Daghani would look back on the period in Bucharest as his most successful: “I was well-known, I had material to work with, my best work came outof a conflict with the socialist regime.”(Bohm-Duchen, Arnold Daghani, 30.)

Daghani can be seen as a victim of canonical Modernism as much as of Cold War politics or, as Andreas Huyssen writes, the “Cold War ideology of modernism as the free art of the West.”(Andreas Huyssen, Twilight Memories: Marking Time in a Culture of Amnesia, New York & London, 1995, 128.) Notions of purity and freedom of expression were confirmed by the language of his admirers whose superlatives he internalized.

Believing that he was a genius, a modern master, and so on, made him feel out of place in Romania, but then also left him disappointed in the Modernist “Free World” that failed to recognize his talent.

In numerous self-portraits, Daghani examines himself, both physically and psychologically, attempting to understand his difficult life, and often perceiving himself as a deluded Don Quixote figure—a naive dreamer who lives a life between fantasy and reality. Daghani’s search for his own artistic and religious identity, both in Romania and elsewhere, seems to have paralleled the conflicts in Romania as it struggled to secure its territorial borders and define itself as a nation.

Although the cultural division of Europe between East and West was a Cold War construct, cultural communication, influences, and aspirations cross geographic borders, albeit through political filters.

It seems that art history has to move away from using binary East-West divisions in its analysis, while taking into account historical and political, as well as art historical, differences in regional experiences. Awkward figures such as Daghani, who do not fit neatly within geographical or cultural borders, and who disrupt binary divisive contrasts, can be helpful tools in challenging preconceptions and in enabling us to examine the complex identities involved.

!['Untitled [Accommodation in Mikhailowka]', February 1943, from the album '1942 1943 And Thereafter' (Sporadic records till 1977).](https://artmargins.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/daghani.jpg)

!['Untitled [Bishop]', Sept. 20, 1959.](https://artmargins.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/RCA68043.jpg)

!['Untitled [self-portrait]', 1966, from the album 'What a Nice World', 1942-77.](https://artmargins.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/RDA68043.jpg)