Dispatch from Sofia (Article)

With the gas light blinking empty the taxi headed towards Sofia. The driver offered me another cigarette after I had extinguished one to get in the cab. “Are you German?” “No American.” I replied. He wagged his finger smiling saying “Monica Lewinsky! Bill Clinton!” I laughed and thought about how wonderful it would be if cultural memory had no recollection of the Bush years. The Balkan mountain range that cradles Sofia loomed ahead.

“Everything is happening for the first time here. It’s the second time which is the challenge,” said the Russian-born Iara Boubnova, co-founder of the Institute of Contemporary Art, Sofia; co-curator of Manifesta 4 and twice co-curator of the Moscow Biennale. We were having lunch near the Museum for Foreign Art in the city center just by Alexander Nevski Cathedral. She was referring directly to the exhibition we had just visited for the nominees of the Gaudenz Ruf Art Prize, in its third edition, and yet indirectly referencing the entrepreneurial potential available in the cultural landscape of Sofia and Bulgaria.

Gaudenz Ruf was Switzerland’s ambassador to Bulgaria in the late 90s and always had a penchant for contemporary art. Seeing himself as one of the few collectors he took it as his duty after retiring to found a prize that can be seen as a modest equivalent to the Tate’s Turner Prize in terms of local stature and spotlight.(The BAZA Award is another prize given by the Sofia City Art Gallery. It gives a Bulgarian artist a six-week fellowship in the prestigious ISCP residency in New York. The winner of the 2009 BAZA Award was Samuil Stoyanov.) The prize gives 2,500 Euro to the category of Advanced Artist and 500 Euro to an emerging artist. The jury was made up of artists, critics and curators Luchezar Boyadjiev, Lorand Hegyi, Vessela Nozharova, Elena Panayotova, and Darko Senekovic. This year was the first one opened up to applicants of the diasporic contingent, a move that offers an interesting counterweight towards reversing the brain drain common in any pre-art-market scenario and getting the young and promising artists who left the country their much-needed local exposure.

Located in a rather anonymous building in the city center I could have been entering a travel agency or an info point only to find this bazaar of local talent. Twenty-some artists took part from varying generations. The exhibition as a whole was sensibly packed with new projects. Some familiar names were Lazar Lyutakov, Kamen Stoyanov, or Milko Pavlov, yet overall I knew so few Bulgarian artists and my knowledge of the local context was so slight that the whole thing was like a blank slate to me. Some complain that those nominated for the Gaudenz Ruf Art Prize are always the same, but in fact the politicking around the prize alone seemed to have a general damned-if-you-do-damned-if-you-don’t sentiment, with some artists refusing to apply or acknowledge the prize due to what was deemed the conventionality of the selection. Whether or not that is true—and as a visitor to the exhibition the quality alone gave a rather stimulating barometer of current practices—nay saying seemed somehow a reflexive tendency.

Located in a rather anonymous building in the city center I could have been entering a travel agency or an info point only to find this bazaar of local talent. Twenty-some artists took part from varying generations. The exhibition as a whole was sensibly packed with new projects. Some familiar names were Lazar Lyutakov, Kamen Stoyanov, or Milko Pavlov, yet overall I knew so few Bulgarian artists and my knowledge of the local context was so slight that the whole thing was like a blank slate to me. Some complain that those nominated for the Gaudenz Ruf Art Prize are always the same, but in fact the politicking around the prize alone seemed to have a general damned-if-you-do-damned-if-you-don’t sentiment, with some artists refusing to apply or acknowledge the prize due to what was deemed the conventionality of the selection. Whether or not that is true—and as a visitor to the exhibition the quality alone gave a rather stimulating barometer of current practices—nay saying seemed somehow a reflexive tendency.

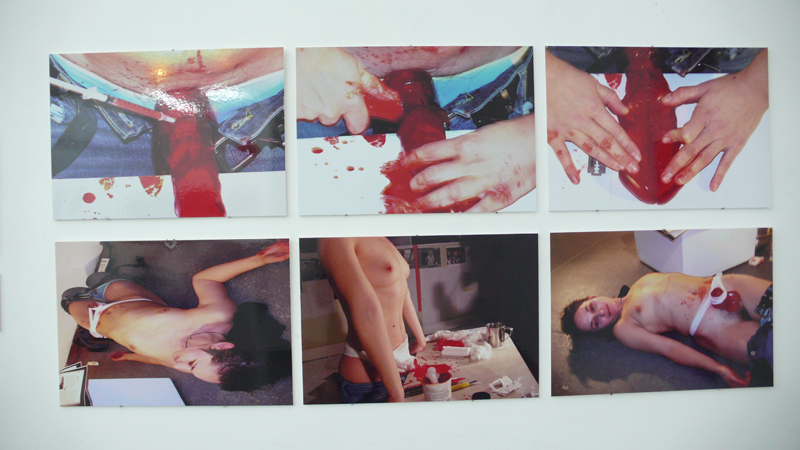

Boryana Rossa made an overt and therefore all the more painful direct reference to Rudolf Schwarzkogler’s iconic castration action from 1966, as a way to address gender and mythologies in art history. The artist performed a stylized penectomy, as she pumped a red-jellied strap-on with anesthetic and proceeded to sever it. Whether or not it was a successful nod to history, it was certainly far from subtle.

Boryana Rossa made an overt and therefore all the more painful direct reference to Rudolf Schwarzkogler’s iconic castration action from 1966, as a way to address gender and mythologies in art history. The artist performed a stylized penectomy, as she pumped a red-jellied strap-on with anesthetic and proceeded to sever it. Whether or not it was a successful nod to history, it was certainly far from subtle.

The work of the London-based emerging artist Stefania Batoeva exhibited a curiously sensible understanding of sculpture as an architectural metaphor. The crude gesso forms were like Corbusian monuments to Tatlin. Cold and yet romantic, like something out of The Fountainhead, the approach felt like some kind of gritty human-scaled logic models for architecture.

The work of the London-based emerging artist Stefania Batoeva exhibited a curiously sensible understanding of sculpture as an architectural metaphor. The crude gesso forms were like Corbusian monuments to Tatlin. Cold and yet romantic, like something out of The Fountainhead, the approach felt like some kind of gritty human-scaled logic models for architecture.

It was an appropriate pairing next to Nadezhda Lyahova, the winner of the advanced artist purse for her work from 2007, entitled Globally and on a long term basis the situation is positive, a Sisyphean loop of video capturing the realities when EU development and Balkan bureaucracies merge. The rickety installation of monitors presented pirouettes of synchronized bulldozers dancing a ballet, or another showing a worker feeding wire into one manhole only to have it removed by a man standing at a hole seemingly meters away. In some way it morphed the banalities of bureaucratic standby and the chaotic lulls of forever incomplete projects into something magical and calculated.

It was an appropriate pairing next to Nadezhda Lyahova, the winner of the advanced artist purse for her work from 2007, entitled Globally and on a long term basis the situation is positive, a Sisyphean loop of video capturing the realities when EU development and Balkan bureaucracies merge. The rickety installation of monitors presented pirouettes of synchronized bulldozers dancing a ballet, or another showing a worker feeding wire into one manhole only to have it removed by a man standing at a hole seemingly meters away. In some way it morphed the banalities of bureaucratic standby and the chaotic lulls of forever incomplete projects into something magical and calculated.

A visit to the Institute of Contemporary Art in Sofia is underwhelming in a clever way. The Institute is reminiscent of that very special Balkan guerilla tactic of titling made famous by Ivan Moudov’s MUSIZ , as in 2005 he successfully branded and launched a fake contemporary art museum in a derelict edifice somewhere in Sofia. The project made for a timely lament on the lack of any such infrastructure. The ICA, on the other hand, was never a one-shot uppercut to bureaucracy or government like MUSIZ and has consistently been a locus for cultural production throughout the last two decades.

Until recently the ICA had no specific location, but nonetheless represented the city’s crème of the established generation, including Iara Boubnova, Luchezar Boyadjiev, Nedko Solakov, and Ivan Moudov, among others, with the club-like structure recalling that of a Kunstverein. Solakov generously lent his old apartment to help establish a fixed location and as of August programming began. The first was entitled Techniques and the ICA’s members were asked one-by-one to select a paper from a grab bag, each leaf specifying an artistic medium in which they would then have to realize a project. In this way, an artist typically working with paint or sculpture might be challenged to do a first-time performance. The results were playfully engaging and offered liberation from standard frameworks or expectations.

The current exhibition was an installation of the 2008 BAZA Award recipient Rada Boukova, with the exhibition entitled Still Life. Cherry picking every possible genre of celebratory balloon available across cultures, Boukova filled the space with something as light and happy as it was dark and political. Each vessel was left to its own slow decline as it released its helium payload and sagged every day closer towards the gallery floor. A comical balloon of the Euro was reportedly the first to touchdown; it sat lopsided and flaccid like a caricature. A star of David, a wedding cake, unicorn, hamburger, surprise you’re forty, I’m sorry you died, Happy Birthday, Congratulations: a spectrum of joy and sadness, anything and everything, a bonanza of Mylar confectionary that pushed and pulled you through every possible human moment in all its scintillating glory. The project recalled somehow a twisted combination of the works of Jeff Koons, Philippe Parreno, and Sylvie Fleury but gave a bit more, was less cold and, it should be said, sincere in its research and scope.

The current exhibition was an installation of the 2008 BAZA Award recipient Rada Boukova, with the exhibition entitled Still Life. Cherry picking every possible genre of celebratory balloon available across cultures, Boukova filled the space with something as light and happy as it was dark and political. Each vessel was left to its own slow decline as it released its helium payload and sagged every day closer towards the gallery floor. A comical balloon of the Euro was reportedly the first to touchdown; it sat lopsided and flaccid like a caricature. A star of David, a wedding cake, unicorn, hamburger, surprise you’re forty, I’m sorry you died, Happy Birthday, Congratulations: a spectrum of joy and sadness, anything and everything, a bonanza of Mylar confectionary that pushed and pulled you through every possible human moment in all its scintillating glory. The project recalled somehow a twisted combination of the works of Jeff Koons, Philippe Parreno, and Sylvie Fleury but gave a bit more, was less cold and, it should be said, sincere in its research and scope.

The tentacles of the ICA wrapped around most every possible aspect of local cultural production. Publications were many, distribution done by hand, and with topics from biennialization to the specifics of how Europe’s itinerant Manifesta biennial affects the careers of Bulgarian artists in the long—and short—term. The artists Sean Snyder and Gelitin also had booklets from previous projects. The recently released book Interface Sofia was a culmination of material and ideas that came out of the Visual Seminar project, an initiative funded by the German Cultural Federation’s Relations program from the latter half of the last decade. The seminar put together a perennial series of books and lectures pairing a single artist and a single academic or theoretician, placing their respective researches into dialogue. This new book, a reader, revisited the total project of Visual Seminar in a retrospective way and offered a second chance to anyone who didn’t manage to come into contact with the initial round of publications.

Commercial galleries are virtually non-existent in Sofia, and beyond institutions such as Sofia City Art Gallery—which, by the way, hosts an outstanding program of curated and solo exhibitions(Beyond solo shows of Ivan Moudov or Nedko Solakov, a particular exhibition of note occurred this summer and was entitled The Temptation of Chalga. Curated by Vessela Nozharova and Svetlana Kuyumdzhieva, the show made for an anthropological analysis of the Bulgarian, and yet generally Balkan, phenomenon of chalga. The Serbian brand of chalga is “turbo folk” and amounts very basically to popular folk-like music usually sung by a woman to a throbbing techno beat. We would probably consider Shakira as our closest thing to chalga today, but here it carries a history of over two decades. It originates in gypsy culture but has become a major influence in everything from fashion and advertising to politics and demeanor. A famous Serbian turbo-folk star is Svetlana Ražnatovi?, known mainly by her stage name Ceca. Beyond being a pop superstar, Ceca is infamous for being the wife of the deceased war criminal General Arken, a major force in Yugoslavia’s violent break-up and responsible for many of the atrocities that marred this period of history. The worst parts of chalga result in a general trashification of culture: breasts, lips, and butts augmented way out of proportion, peroxide blondes with bronze patinas, billboards that mediate a level of sexualized decadence somehow assumed of today’s generation and yet totally out of touch, as the reality of chalga is that most cultured youth regard it with disgust and resentment. In Bulgaria the chalga climax would probably be found in Azis, a gay gypsy Elvis-type whose highly lucrative branding has occupied some of the more shocking ad space (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6ckvuX7jo_g). On the other hand, tourists like myself find chalga to be an utterly sublime rollercoaster of everything one could want from the modern discothéque experience and chalga clubs are highly recommended. The exhibition at the Sofia City Art Gallery dug into the history of the movement’s Bulgarian pedigree, embracing it by providing chronologies parallel with politics and culture, a selection of art works that (over-) emphasized the hyperbolic baroque bling associated with being a chalgar, and generally gave a necessary analogy to help understand how integral and maybe essential chalga is for cultural identity in Bulgaria, even though many prefer to blind an eye to it. It is the kind of exhibition that makes you realize how contributive modes of display can be for a cathartic understanding of oneself through those cultural skeletons that many would rather see buried. The extent of the research seemed to easily fill a book, however none was ever made.) –one’s options for non-profits are limited. ARC Projects, the commercial gallery with the most international profile and representing an index of the country’s artists, has tapered back its programming and was unfortunately not a visit on my tour. Other spaces which blossomed of late are Ivan Assen 22, run by Neli Miteva and hosting more fashion than art, while using dramaturgical aspects of display. By curating rotating presentations of local designers it made for a fantastic immersion into current trends in clothing design. Another is The Fridge, what was described to me as a bourgeois squat that while having a shoot-from-the-hip style of programming also functions as a place to find issues of Vice Bulgaria and other art & design rags. In addition to these, Studio Dauhaus, run by Yovo Panchev, or Iva Galabova’s Plastelin Gallery were each giving a next-generational approach to a local spirit that could be best described as downright activism for the sake of developing further models. The programming seemed for some still to be finding its way, and, with Boubnova’s mantra about the challenge of the second time echoing, this correspondent hoped they would be given the opportunity to find it.

It seemed that patience was the real mantra. Many people get fed up with waiting—whether for the government or some neo-capitalist to fill a gap—and DIY infrastructure becomes the nostrum. Gaudenz Ruf told me that one of the biggest problems in the current state of Bulgaria’s art world was that “those who have culture have no money, and those who have money have no culture.” A commercial gallery has a hard time for that very same reason, due to the nouveau riche investing in more pop than culture.

However for me what has been interesting about Bulgaria–and it must be re-emphasized that my knowledge of the context is indeed slight–is that the lack of market has stimulated a series of alternative trajectories, where artists produce, writers write, and curators curate for different reasons. And while the economic crisis has tightly closed all Western wallets to the arts, working for no money is less shocking here than in some other places and investing one’s love hours is what tends to be the currency. Often artwork is made more to cater to the likes of curators, and as such it possesses deeper social/cultural/political questions–and attempts to engage with the context outside the white walls. In this respect, it made much of the work from artists of roughly equivalent stature in London or New York seem altogether un-ambitious, sheltered, and afraid. People risk a lot more when there is nothing to gain and nothing to lose, and in this case it shows.