Cyberfest 2014

CYBERFEST 2014, KUNSTQUARTIER BETHANIEN, BERLIN, DECEMBER 12-15, 2014; PLATOON KUNSTHALLE, BERLIN

One evening last December, an exhibition hall of the Art Center at Kunstquartier Bethanien, a handsome 19th-century building on Berlin’s Mariannenplatz, was bustling. It was a usual opening night – with food, wine, crowds of people young and old getting together and talking about art. What could have caught a local by surprise was that most of the visitors spoke Russian. Cyberfest, a yearly festival of new media, which originated in St. Petersburg in 2007, was making its second appearance in Berlin, following its debut in the German capital the previous year. Anna Frants, an artist, curator, and the main financial and organizing force behind the festival, was there with her usual camera hanging around her neck, snapping pictures. Marina Koldobskaya, also an artist and a co-curator of the exhibition in Berlin, was mingling with the crowd. Frants and Koldobskaya came up with the theme of the festival and brought together artists whose work addressed displacement, and relocation. The resulting satire, humor, or nostalgia restage the loss of place as a lasting performative event. One installation that most clearly reflected both technological ambition and the thematic orientation of the exhibition was made by sound artists Sergei Komarov and Leta and Vladislav Dobrovolsky, with technical assistance from Alexey Grachev. Entitled Kitchen, it consisted of 12 black rectangular drawers of various sizes hanging on a wall in an irregular formation. Each time a drawer was opened by a visitor, a continuous mellifluous sound would come out; with multiple drawers open simultaneously, the viewer – and listener – would be plunged into an immersive musical experience.

For Frants, the inspiration for the festival came from the famous 1960s cooperative E.A.T. (Experiments in Art and Technology). E.A.T. served as a hub for encounters and collaborations among artists and engineers, promoting their alliance and resulting in such well-known projects as 9 Evenings: Theater and Engineering (1966) in New York and the Pepsi Pavilion at Expo ’70 in Osaka. Following in the footsteps of Billy Klüver, the co-founder of E.A.T., as well as the 1960s luminaries who either co-founded or participated in E. A. T. or both, such as Robert Rauschenberg and John Cage among others, Frants decided to launch a collaborative enterprise of artists and engineers who would enact an alliance of art and technology. Having found an enthusiastic and skillful partner in Koldobskaya, Frants then organized the first Cyberfest in St. Petersburg. There, Frants premiered her performance Speedless, in which she wore a helmet with video glasses, replacing her normal vision with images and sounds, which varied depending on the movement of her body. She also invited Julie Martin, Klüver’s partner and collaborator to give a lecture about E.A.T., including a screening of Rauschenberg’s film Open Score, which was part of 9 Evenings. There was also a restaging of Silver Clouds, Andy Warhol’s work made with Klüver’s help, with pillows floating freely around the room, originally shown at Leo Castelli Gallery in 1966.

In its brevity, the first Cyberfest served as an introduction to the festival, which took place each November in St. Petersburg and Moscow for five years in a row. Frants assembled a seven-person curatorial team to run the festival. From the very beginning, it was associated with Cyland, a “media art lab,” which defines itself as an international community of “artists, critics, curators, engineers and media activists” interested in “creating and promoting art that meets the level of today’s civilization development.”(http://www.cyland.org/site/russian/about-us) Its name, a compound of “cyber” and “island,” refers to cybernetics on the one hand, and a place separated from “the profane life of business, politics, and pop culture,” on the other. The metaphor of displacement is apposite, since Cyland exists in the virtual space of a website – and uses language – English as well as Russian – to define itself; Koldobskaya compares its structure to that of Fluxus. Initially, however, Cyland had a more concrete physical grounding: the collective began as an art residency administered by the National Center of Contemporary Art, which Koldobskaya directed at the time, and it was located on an actual island – Kronstadt near St. Petersburg. According to Koldobskaya, the relationship of Cyland to Cyberfest is that of an experimental laboratory to the annual showcase of its activity. With time, as Cyland moved into cyberspace, the collective’s festivals remained open to artists who were interested in new media and technological experimentation, but were not considering this as the only direction of their activity. Some of them used Cyland as an opportunity to transform their art, originally based in traditional media, into technologically advanced installations. Some were intrigued by a particular theme of each exhibition, finding in it a perfect occasion for expressing their ideas concerning life, death, and human destiny. Over the years, the mission of Cyberfest shifted from an exclusive focus on state-of-the art technology toward Marshal McLuhan’s view of media as anything that transmits information.

In its brevity, the first Cyberfest served as an introduction to the festival, which took place each November in St. Petersburg and Moscow for five years in a row. Frants assembled a seven-person curatorial team to run the festival. From the very beginning, it was associated with Cyland, a “media art lab,” which defines itself as an international community of “artists, critics, curators, engineers and media activists” interested in “creating and promoting art that meets the level of today’s civilization development.”(http://www.cyland.org/site/russian/about-us) Its name, a compound of “cyber” and “island,” refers to cybernetics on the one hand, and a place separated from “the profane life of business, politics, and pop culture,” on the other. The metaphor of displacement is apposite, since Cyland exists in the virtual space of a website – and uses language – English as well as Russian – to define itself; Koldobskaya compares its structure to that of Fluxus. Initially, however, Cyland had a more concrete physical grounding: the collective began as an art residency administered by the National Center of Contemporary Art, which Koldobskaya directed at the time, and it was located on an actual island – Kronstadt near St. Petersburg. According to Koldobskaya, the relationship of Cyland to Cyberfest is that of an experimental laboratory to the annual showcase of its activity. With time, as Cyland moved into cyberspace, the collective’s festivals remained open to artists who were interested in new media and technological experimentation, but were not considering this as the only direction of their activity. Some of them used Cyland as an opportunity to transform their art, originally based in traditional media, into technologically advanced installations. Some were intrigued by a particular theme of each exhibition, finding in it a perfect occasion for expressing their ideas concerning life, death, and human destiny. Over the years, the mission of Cyberfest shifted from an exclusive focus on state-of-the art technology toward Marshal McLuhan’s view of media as anything that transmits information.

When it was held only in Russia, the festival was considered international, because it always included artists from other countries, especially where video and sound art were concerned. Many were represented by Brooklyn gallery Dam Stuhltrager, which brings together art and technology and is owned by Leah Stuhltrager, a Cyberfest curator. In 2013, Cyberfest expanded to Berlin, where Stuhltrager ran The Wye, an art-and-technology hub. Last December, Berlin was the fourth stop on the itinerary of the festival, which opened on November 5 in St. Petersburg with a performance by Ken Butler, an experimental musician and artist from the United States. On November 18, it moved to Khodynka in Moscow for another sound art program curated by Katya Bochavar; on November 29, it relocated to Tokyo’s Sky Gallery for an exhibit and performance curated by Stuhltrager. After Berlin, New York hosted the video program of the festival, curated by Victoria Ilyshkina. In all venues taken together, the spread between native Russian speakers and foreigners was rather even: among 46 participants in Cyberfest 2014, a few more than half were from Russia originally.

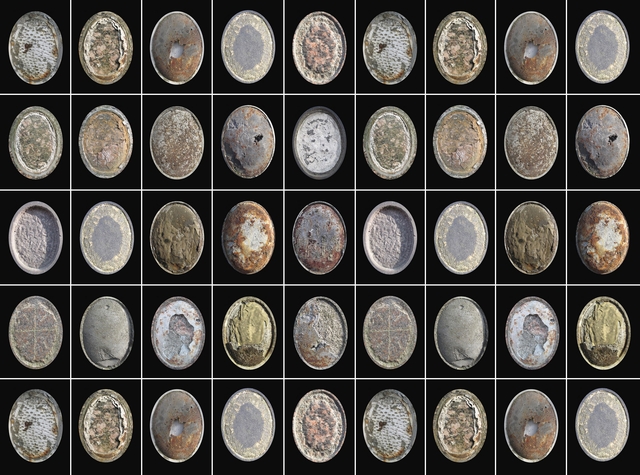

In Kunstquartier Bethanien, the exhibition occupied six cavernous rooms of the former deaconess institute built by Friedrich Wilhelm IV– half-hospital, half-fortress – where nineteen artists displayed their works. On one side of the narrow entrance hall hung Lyudmila Belova’s Archive (2002-2014), a wall-mounted arrangement of 6 uniform wooden boxes with peepholes through which a viewer could see photographs of entry halls into St. Petersburg buildings. The images were found by Belova after they had been discarded by a real estate agency. Each box was equipped with a set of headphones, transmitting sounds associated with life in a building, music, steps, fragments of conversations, falling water different for every foyer. The incalculable distance between the viewer and the viewed accentuated by photography and the magnifying glass of the peephole was bridged by audio-technology, creating a nostalgic reminder of a particular time and place, but also localizing this nostalgia in a rather simple construction. Opposite Belova’s hermetic boxes, Alexander Terebenin placed another arrangement for nostalgic recollections: Last Portrait (2014), a giant rectangle composed of 45 commemorative photographs, which are usually found in Russia on crosses, steles, or other monuments placed atop graves. With the flow of time, the faces on these images fade, replaced by abstract shapes and remnants of representation. Terebenin printed photographs of these disappearing images on silk, framed them, and arranged them in a grid – presenting to our view the “last portrait” of humanity.

In Kunstquartier Bethanien, the exhibition occupied six cavernous rooms of the former deaconess institute built by Friedrich Wilhelm IV– half-hospital, half-fortress – where nineteen artists displayed their works. On one side of the narrow entrance hall hung Lyudmila Belova’s Archive (2002-2014), a wall-mounted arrangement of 6 uniform wooden boxes with peepholes through which a viewer could see photographs of entry halls into St. Petersburg buildings. The images were found by Belova after they had been discarded by a real estate agency. Each box was equipped with a set of headphones, transmitting sounds associated with life in a building, music, steps, fragments of conversations, falling water different for every foyer. The incalculable distance between the viewer and the viewed accentuated by photography and the magnifying glass of the peephole was bridged by audio-technology, creating a nostalgic reminder of a particular time and place, but also localizing this nostalgia in a rather simple construction. Opposite Belova’s hermetic boxes, Alexander Terebenin placed another arrangement for nostalgic recollections: Last Portrait (2014), a giant rectangle composed of 45 commemorative photographs, which are usually found in Russia on crosses, steles, or other monuments placed atop graves. With the flow of time, the faces on these images fade, replaced by abstract shapes and remnants of representation. Terebenin printed photographs of these disappearing images on silk, framed them, and arranged them in a grid – presenting to our view the “last portrait” of humanity.

Throughout the exhibition, Petr Shevsov displayed his Toilet Bacchanalia (2014), a series of erotically charged works. His ideal, he said, would be to install an actual bathroom in the exhibition space – complete with toilet and other excremental paraphernalia. Because he was not presented with this opportunity, he had to limit himself to painting lascivious scenes of love-making performed by figures modeled after ancient Greek vases atop portions of the wall inlaid with bathroom tiles. Turning a corner with one of his works, a visitor arrived at a room with an installation by Elena Gubanova and Ivan Govorkov, a husband-and-wife team who have been working together since the early 1990s. Entitled Eclipse and made specifically for this exhibition, it lives up to its name by visually reenacting on a screen an eclipse of a circle of light by a round black shape accompanied by an audio track of wind, music, and disorienting sounds suggesting an approaching apocalypse. The cycle regenerates after darkness engulfs light completely. A technologically complex work, which used a projection of the sun photographed through a telescope and the animation of the moon, Eclipse mixes references to an actual phenomenon – as an astronomer’s daughter, Gubanova grew up observing eclipses and other cosmic events – with symbolic connotations of the eternal fight of good against evil and a dynamic of perpetual change, linking changes in nature with those in culture. Kazimir Malevich’s historic design for the avant-garde opera Victory over the Sun served as an inspiration. Gubanova and Govorkov are among a handful of artists who form a permanent core of the Cyberfest team. Since they began exhibiting with the festival in 2010, Gubanova and Govorkov have produced several technically challenging pieces in collaboration with engineers and other technicians. Credit for the creation and installation of Eclipse also goes to Alexey Grachev, an engineer, and Viktor Ryukhin, a video technician. The two men are a part of a team of technical specialists assembled by Frants and Koldobskaya that stands behind Cyberfest and ensures the success of its mission.

Throughout the exhibition, Petr Shevsov displayed his Toilet Bacchanalia (2014), a series of erotically charged works. His ideal, he said, would be to install an actual bathroom in the exhibition space – complete with toilet and other excremental paraphernalia. Because he was not presented with this opportunity, he had to limit himself to painting lascivious scenes of love-making performed by figures modeled after ancient Greek vases atop portions of the wall inlaid with bathroom tiles. Turning a corner with one of his works, a visitor arrived at a room with an installation by Elena Gubanova and Ivan Govorkov, a husband-and-wife team who have been working together since the early 1990s. Entitled Eclipse and made specifically for this exhibition, it lives up to its name by visually reenacting on a screen an eclipse of a circle of light by a round black shape accompanied by an audio track of wind, music, and disorienting sounds suggesting an approaching apocalypse. The cycle regenerates after darkness engulfs light completely. A technologically complex work, which used a projection of the sun photographed through a telescope and the animation of the moon, Eclipse mixes references to an actual phenomenon – as an astronomer’s daughter, Gubanova grew up observing eclipses and other cosmic events – with symbolic connotations of the eternal fight of good against evil and a dynamic of perpetual change, linking changes in nature with those in culture. Kazimir Malevich’s historic design for the avant-garde opera Victory over the Sun served as an inspiration. Gubanova and Govorkov are among a handful of artists who form a permanent core of the Cyberfest team. Since they began exhibiting with the festival in 2010, Gubanova and Govorkov have produced several technically challenging pieces in collaboration with engineers and other technicians. Credit for the creation and installation of Eclipse also goes to Alexey Grachev, an engineer, and Viktor Ryukhin, a video technician. The two men are a part of a team of technical specialists assembled by Frants and Koldobskaya that stands behind Cyberfest and ensures the success of its mission.

The performative enters Cyberfest through interactive three-dimensional installations. Frants’ On the Lookout (2014) featured a mounted deer head with moving eyes. Built-in motion sensors detect people’s movement at a certain distance; a surreal sense of being observed by a dead animal is the intended effect.(http://annafrants.net/home_38.html) Alexander Shishkin-Khokusai, a scenographer, mounted another installation that assaulted visitors’ senses. In Print Opera (2013-2014), roughly hewn human heads made out of cardboard and mounted on wooden stands were brought into motion by an electric circuit initiated by pressing a button. Meanwhile, typewriters connected to the same circuits type nonsense and spout mounds of paper. The cacophony of noise and clatter ends only when the electric circuit automatically disconnects. A separate room held installations by Bochavar and Vitaly Pushnitsky as well as a video animation by Marina Alexeeva – none of which, taken separately, was significantly advanced in technical terms, but together they formed a unit about alternate domesticity. Other works in the exhibition, such as Alexander Dashevsky’s Mortgage Languor (2014) and Petr Belyi’s Dream and Ball (2014), also explored various aspects of life associated with one’s attachment to a place, on the one hand, and our relative mobility, on the other. A painting and an installation respectively, they address the question of what it means to belong to a place and how this sense of belonging can be demonstrated in a work of art. Austrian artist Peter Lederer asked the same question when he displayed some 230 salt stones diversely shaped through continuous cows’ licks – cows licking stones being a commonplace sight in Austrian villages. The display was accompanied by a video of an unknown musician, performing songs from the artist’s youth.

The performative enters Cyberfest through interactive three-dimensional installations. Frants’ On the Lookout (2014) featured a mounted deer head with moving eyes. Built-in motion sensors detect people’s movement at a certain distance; a surreal sense of being observed by a dead animal is the intended effect.(http://annafrants.net/home_38.html) Alexander Shishkin-Khokusai, a scenographer, mounted another installation that assaulted visitors’ senses. In Print Opera (2013-2014), roughly hewn human heads made out of cardboard and mounted on wooden stands were brought into motion by an electric circuit initiated by pressing a button. Meanwhile, typewriters connected to the same circuits type nonsense and spout mounds of paper. The cacophony of noise and clatter ends only when the electric circuit automatically disconnects. A separate room held installations by Bochavar and Vitaly Pushnitsky as well as a video animation by Marina Alexeeva – none of which, taken separately, was significantly advanced in technical terms, but together they formed a unit about alternate domesticity. Other works in the exhibition, such as Alexander Dashevsky’s Mortgage Languor (2014) and Petr Belyi’s Dream and Ball (2014), also explored various aspects of life associated with one’s attachment to a place, on the one hand, and our relative mobility, on the other. A painting and an installation respectively, they address the question of what it means to belong to a place and how this sense of belonging can be demonstrated in a work of art. Austrian artist Peter Lederer asked the same question when he displayed some 230 salt stones diversely shaped through continuous cows’ licks – cows licking stones being a commonplace sight in Austrian villages. The display was accompanied by a video of an unknown musician, performing songs from the artist’s youth.

The sound art program of Berlin’s Cyberfest took place in Platoon Kunsthalle, where five specialists in electronic sound – among them Pete Um — performed their compositions. All of the festival’s sound art programs are curated by Sergei Komarov, a computer programmer from Kaluga, who joined Cyberfest as a technical specialist in 2009. In a short time, he took charge of the festival’s sound installations and Cyland’s sound archive, assembling an impressive record of contemporary electronic music. The festival concluded on January 15, 2015, with a one-evening program at Made in New York Media Center in Dumbo, Brooklyn, where Ilyshkina put together a program of 18 videos by international artists, some of whom are featured in Cyland’s video archive, also assembled by Ilyshkina. The videos ranged from animated clips, such as Plasticity Unfolding (2014) by AUJIK, to narrative and performative features, such as Forrest (2011) by Rasmus Albertsen and Just My Own (2014) by Alena Tereshko. The program lasted just over one hour; the curator succeeded in making the screening engaging and informative.

The sound art program of Berlin’s Cyberfest took place in Platoon Kunsthalle, where five specialists in electronic sound – among them Pete Um — performed their compositions. All of the festival’s sound art programs are curated by Sergei Komarov, a computer programmer from Kaluga, who joined Cyberfest as a technical specialist in 2009. In a short time, he took charge of the festival’s sound installations and Cyland’s sound archive, assembling an impressive record of contemporary electronic music. The festival concluded on January 15, 2015, with a one-evening program at Made in New York Media Center in Dumbo, Brooklyn, where Ilyshkina put together a program of 18 videos by international artists, some of whom are featured in Cyland’s video archive, also assembled by Ilyshkina. The videos ranged from animated clips, such as Plasticity Unfolding (2014) by AUJIK, to narrative and performative features, such as Forrest (2011) by Rasmus Albertsen and Just My Own (2014) by Alena Tereshko. The program lasted just over one hour; the curator succeeded in making the screening engaging and informative.

In the seventh year of its existence, Cyberfest is going through a period of change. Since its expansion beyond Russia’s borders, it is trying to find its audience. While in Russia this audience was a given – bringing technically advanced art and foreign artists to St. Petersburg and Moscow was a noteworthy and welcomeevent – the effort to reverse the flow and find an audience for Russian artists abroad is a more difficult task. From a broad, art-world perspective, Cyberfest 2014 presents itself as a showcase for a team of artists and curators from Russia making a push to expand their art beyond their country’s borders and integrate it into other communities. Judging by the curators’ determination and the quality of the work shown during Cyberfest 2014, the festival’s extended venture into a hands-on exploration of the relationship between art and technology has a chance to succeed, establishing itself in the West as well as it has done in Russia. The trick is to connect with the local communities in the cities where the festival wants to make its “other homes.”