Comics and Temple: “Here” and “There” in Contemporary Bulgarian Art

I suppose the organizers of the conference “Is There Anything In Common Between Here and There In Contemporary Art?” meant by the title a geographical and national correlation, a juxtaposition on the horizontal line of real space.

However, such deictics as here and there do not define space unambiguously. Rather, their definition depends on the speaker’s situation in space, as well as on his or her will. The otherness, promised both by the conference title and the exhibition title, “Ars ex Natio: Made in Bulgaria,” is related to some territorial or social aspects defined by nationality.

The wrong wording of the Latin part of the title is perhaps in itself a manifestation of an attitude toward the foreign, toward otherness. A grammatically correct wording would have been “Ars ex Natione.”

But of course, I could find a deliberate absurdity in the title and read it as “Ars Ex-Natio,” something like “Art Former-Nation,” a construction that would thus enlist art (and/or nation) under the topic of absurdity, a notion that would not be out of place after three decades of appeals for the death of art.

The premise I would like to criticize is that “here” and “there” are considered to be monolithic-an impression which is confirmed by the exhibition poster, made by Kiril Prashkov, featuring cobblestones floating away in the blue sky.

Indeed, Prashkov is playing with the national emblems, such as the yellow cobble stones of Rouski Boulevard(Rousski is historically the most important boulevard in Sofia.) (which were imported from Vienna), embodying the juxtaposition of the heavy weight (of national art) nevertheless floating in the air-and yet the national remains a compressed stone.

The concept of national art suggested by the poster is monolithic-but the national is not. The second part of the title-“Made in Bulgaria”-adds to such a singular perception because it is also a nationally totalizing commodity and an ideological stamp. I prefer to take another stand; namely, that the national is multiple, that it (“here”) is an inner conflict.

So the title of the theoretical conference is characterized by the two monoliths of “here” and “there,” on the one hand, and by vagueness on the other hand. So, if we assume that “here” is the space limited by the national territory, what is “there”?

I prefer to drop the national determinants so as not to criticize the given framework. And yet, in order to stick to the title, let me choose another correlation of “here” and “there.”

I prefer to think of “here” and “there” as a relation along a vertical and valuable line, rather than in terms of social or national geography, a relation that can be religious and ethical.

The relationship with God is a relationship with the perfect “Otherness.” The only reason to recognize and live with othernesses is the ethical character of my relationship with the transcendental.

In other words, my otherness and the foreign one have their grounds in the transcendental and the divine, and in correlation with any otherness, my ethical (and existential) grounds are put on trial.

I collapse back to a pre-Christian and precivilized state every time I am determined to destroy otherness (whether mine or foreign)-without it threatening me-in order to confirm that which is “my own” and especially when such confirmation has become a natural social reflex; when it has been transformed into nature.

This is why I have chosen works where the otherness is expressed by an attitude to religion, as is the case with Luchezar Boyadjiev, or transcendence, exhibited in the works of Nadezhda Lyahova.

The artistic projects of Luchezar Boyadjiev offer a decomposition of famous stories whose identification is left to the public.

Frequently they represent deliberately banalized fragments with an absurdist shade, instead of exhibiting narration. An essential question is whether the artist does not fall into the trap of the cliché and banality that he himself has set for the public.

If I did not know Luchezar Boyadjiev personally, I would not have been able to so directly perceive a peculiarity of contemporary conceptual art, one which appears to be emblematic: The artist is simultaneously in the role of an interpreter of his own work.

The explanations are an indispensable part of the project because the form, the image, is not expressive enough in itself and cannot stand on its own.

The analytic attitude prevails in the explanation of the concept to which the image is only an addition. Can the image, the form, and the plastic itself be the carriers of the concept without having the need for the artist’s interpretations as a part of the work?

The texts accompanying the exhibitions explain to the public “what the author has meant”. With the author’s intentionality represented, the viewer is perhaps not expected to discover or to interpret meaning.

So what is left for the viewer? The question seems essential: Does conceptual art presuppose any interpretation and, if not, how is it oriented to the viewers-and who are they? And finally: What should their behavior be?

Educated as an art critic, Luchezar Boyadjiev explains his works’ concepts and his own author’s presence in a language that is updated-for instance, he avoids the modern idea of the author being exceptional, which has become a cliché.

He simply makes inventive collages from fragments of meanings that already exist. In his latest publication, titled “Exempli causa-vice versa,”(Luchezar Boyadjiev, “Exempli causa-vice versa,” Kultura Weekly, 11 April 1997, 12.) his idea is to put together two Latin clichés splinters, and this title illustrates Boyadjiev’s conception of the artist and hence his taste for the banal and for what is jeopardized by the act of banalizing.

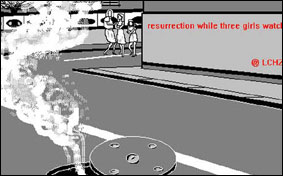

In his latest installation, Updated Gospel-short (cover) version, shown in 1996 and 1997 at the Ata-Ray gallery (and before that in St. Petersburg), we can read text pieces on the graphics and hear them from the video and, in a provided folder, we can get some information about the idea of the installation.

Attached on one of the walls are long paper bands, forming a street space with definitive abstractedness. In the center of the graphic piece (in the foreground, attracting the viewer’s glance at once), we can see the heavy lid of the sewage system pushed away.

From the opened shaft, white steam is floating up. Its lack of outlines contrasts with the clearly outlined space of the street. In the far background, we see three female figures that have turned toward the lid, the shaft, and the steam.

A sort of happening-a newspaper photograph, a movie sequence, a reportage-whose explanatory text, printed in English, is “resurrection while three girls watch and wonder”-it is as if I am not reading a foreign newspaper.

Perhaps that has happened abroad, or perhaps American language is functioning as lingua franca, as media koine valid everywhere. In short, I am not moved by that happening so I turn back. It is part of the workday chronicle filling up newspapers, just another drop in the flow of “pseudosensations.”

That would be my reaction had I caught a glimpse of this photo in a daily paper. However, I am in a gallery and I see that which is offered as art; hence it requires more attention.

Everybody knows that, in art, there are deep layers, symbols and allegories, inter-textuality, palimpsests, and tutti quanti. Well, let us see what the so-called tutti are.

I am inclined to start with the computer graphics because they allure me with the tension between the rectangular segments and the round lid and shaft, with the figures cut into small squares, with the overlapping right-angled forms, and the steam’s lack of contour, milk white against the graphic sharpness of the rest of the space.

And finally, I am attracted by the figures of those women, stiff with fear and curiosity, who seem to have witnessed something both frightful and tempting.

I would like to know who these three women are. Following the title we can imagine that they are the three Marias, coming to the tomb of Christ, but such a hasty identification misses the corporeal intrigue that we can trace from the work.

Someone, it appears, has detonated the lid of the shaft. On the other hand, there may not have been any detonation; the lid may have just been removed for some repairs, and the three “girls” may just be peering curiously while passing by.

Is there anything in the image that can prevent such newspaper (reportage) perception, or can the representation (the art) that tried to present itself as secondary signified banality be easily diluted in it?

Above one of the sidewalks is a long billboard-like wall with the already-mentioned English caption. Girls, like the Bulgarian devojki [lasses] is a successful find-it designates a specific age group, but also the frequenters of night clubs and whore houses-so that we are additionally “moved” to decipher the phrase.

Below this are the initials of the firm or of the master restorer/renewer-@ LCHZR BDJV 96-which could belong to Luchezar Boyadjiev, who would claim seriously that the initials within the conventional space of the graphic work and the ones of the living person are the same and, furthermore, that the letters are coded here in a way, characteristic of writing in some Arab countries (hence the association with a terrorist act), and which, to top it all, are licensed in the wrong way with the “at” symbol used for email, instead of the Jus autoris.

Things get interesting: Someone restores a subversive activity, detonating (or simply removing) the street lid, in an area that is quite deserted at that instant, indicating that a certain activity is underway underground.

Those who happen to be there can look at the place with the eyes of people reading the daily paper, but the displacing-the detonation-could affect them and cause a reaction, a certain inner convulsion in them, despite their will to the contrary.

I feel the state of the figures lacks expressiveness; it could be more intense, more convincing, but we should remember that the image is auxiliary to the conception, and because it is conceptual art, the public should be pleased that it still exists.

I imagine that “watch and wonder” is written for the sake of alliteration and also to describe the everyday behavior of undisturbed, distant curiosity. We neither know where the girls are coming from, nor where they are going.

If we ask the usual for the situation question “Quo vadis, quo vadite?” we are not sure that the answer will be, “To the tomb of Jesus.” On the other hand, we can imagine that the positions of the stiff figures and their displaced faces seem to reflect the power of the sound wave to move away of the shaft’s lid and that the figures express something more than curiosity.

In a previous variant of the installation, the figures (the women silhouettes) really expressed only curiosity. Nothing more.

However, the author’s explanatory text reads, “Hands, gestures, crying, etc.” The artist has added in words what the viewer has to notice. I would like the image to bear the idea of everyday life in which a miracle can detonate, which on its behalf can suspend the validity of everyday life and its inner attitudes and can overturn it.

I would like the graphic work to suggest, through the impersonality of the chronicle, the idea of eternity. But I am not sure whether those are not just my wishes which, although stirred by the graphic work, are not suggested by it. Nor am I sure that only “here” exists with the clear absence of “there” or “beyond,” the latter of which I would like to see present as well.

And yet, there is an allusion to religiousness in the possible reading of the word resurrection. If I were not aware of the author’s inclination to play with words, I would think he had been careless or lacked knowledge, writing the word resurrection with a lowercase r and without the definite article, so I prefer to interpret the word in its other meanings, rather than as “The Resurrection.”(I think of “A Moderate Avant-Garde within the Framework of Tradition.” Boyadjiev gave this title to an exhibition, in which he was also participant, parodying the local idea of the avant-garde in the year of 1990. The phrase is a deliberate change of Jaroslav Hasek’s phrase, “Party for a Moderate Progress in the Framework of Law.” Cherry cannon (made from cherry trunk) was the weapon used in the greatest Bulgarian rebellion, against the Turkish Empire in 1876, a heroic and tragic symbol in the so-called struggle for liberation; despite the great hopes of the rebels, the self-made cherry cannon proved unsuccessful. In a conversation with the artist Georgi Todorov, known for his extreme interest in the Bulgarian national cultural heritage, he conjectured that by “cherry cannon” Boyadjiev meant a small “cannon ball” for children’s game.)

Even viewing only for that “mistake,” I would not fall into the banal assumption that the image would refer to the culmination in the life of Jesus Christ, that there would be something religious in the graphic work. This is a quandary to solve; it is still not obvious.

And yet the phrase could be read as “(The) Resurrection while three girls watch and wonder,” which is somewhat deprived of logical meaning; this is not “The Resurrection” that you see, but “The Resurrection” only while it is being seen-a kind of hallucination, a collective mirage-and one cannot claim anything with certainty about its actual happening.

I am inclined to follow such a line of perception: The three figures are shaken by the hallucination of someone’s Resurrection or simply by an activity that is beneath their conscience. What we see is the inner state of the three figures whose personalities could come into being exactly because of this hallucination/happening; they could be inwardly “overturned,” converted.

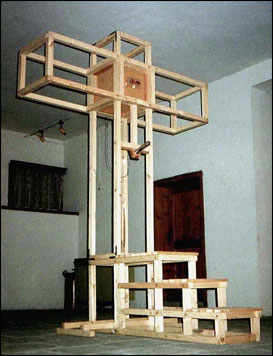

Luchezar Boyadjiev has two other projects, titled Pulpit-Cross (1994) and Eye-Cross (1994), wherein the religious attitude is presented as a chance for personal manifestation or a look into oneself. Especially in Eye-Cross it is presented to the viewer as an inner state of mind.

I would like to point to the modern tradition of the gaze to which Eye-Cross belongs-that is, looking through a peephole, secretly, at the theater of one’s own hidden desires. I, the one who is looking, am the observer of another and unknown self of mine, of more than one, of many, driven by desires, who are not only unknown to me, but also alien. I am watching my alien selves as a possible crucifixion through the peephole.

What happens afterwards? In the author’s explanation, the three girls close the shaft and pass by. And then the happening is repeated in a ping-pong manner. Such is the compositional idea of the author: The workday covers the wonder that is repeated time and again without stopping and without either purpose or meaning.

Why should we look into the work of a contemporary artist so thoroughly? Does such a meticulous approach not go beyond the installation’s own pretensions?

The formal grounds for such scrutiny can be the fact that we are facing a fictitious space, one which does not coincide with the real viewer’s space and where the viewers have to orient themselves by analyzing what they have seen. The presence-or absence, as is the case-of a frame does not overcome the distinction of fiction-reality.

Beyond these formal grounds, however, something else is essential in evaluating this art. Contemporary art in Bulgaria, calling itself unconventional, is often willing to fascinate the sponsor and the curator more than the viewer.

Because of its fixation on the mass media, contemporary art, unlike avant-garde art, starts to acquire a taste for sensation and suffering, not from its lack of social prestige, but because it may be short on impact on the viewer.

It is very difficult to answer the question of for whom art is meant. It seems socially integrated, and yet we still ask “Who is its public?” and-if there are any viewers at all-“Are they affected by it?” It is hardly possible to speak about total approval or admiration.

Admiration and most of all adoration are kept only for the art of the past after it has acquired a classical status. Exceptions are found abroad, and is not the topic here “What is ‘Made in Bulgaria'”?

So, despite the intentional transience of an installation, it is worth trying an attitude toward it as if it were a classical work deserving all the public’s attention, a serious attitude with great expectations to find out if the installation can satisfy them.

The viewers should ask basic questions and expect the respective answers. We in turn should legitimize what has been offered as art through our engagement so that it cannot exist without us.

The viewers should not be influenced by the representativeness of the exposition (famous museum or private gallery, embassy or insurance building, or open air); they should not be impressed by the sponsors’ names-we should, rather, follow (as far as possible) our existential attitudes.

Our judgment should be based on a combination of the aesthetic and the ethical. In short, the public could try to be more unconventional than the art itself in order to test whether that which is offered as art deserves such a designation.

In its huge variety of activities, practices, and forms, contemporary art challenges the public to take the responsibility to define what art means to us, not only to ask if this object, installation, or happening is good, but also if it is art, and-consequently-what art is.

Because that comes to be without compulsion, the engagement with contemporary art could be a model for a social engagement, too.

I speak of public and art as singular nouns, but it is obvious that both can be thought of only in plural.

To put it another way: Can contemporary art be a test, an examination of the public’s sensitivity, personal experience, and ethical values? Can it, without going back to categories like beauty and autonomy, be an alternative to a reality experienced as unsatisfactory and alien? If not, then why does it exist?

As a viewer, I can relate to any kind of art (conventional or not) only if it offers me an experience related to the reasons of my being-that is, only if, through my attitudes toward art, I can reach, rethink, even overturn that which I accept to be my existential foundations.

My impression, however, is that I constantly run into unconventional projects whose self-reference, related only to their author, constructs the private strivings of the artist’s well-being.

Unconventional art in Bulgaria will legitimize itself when it manages to create a space to put on trial social realia and authority establishments that the public will be encouraged to parlay into its own trial; in short, when a minimum utopian and an as yet socially impossible intention is active in that kind of art.

We know both the type of representation and the ideas in the graphic work of Luchezar Boyadjiev: the deleting of the border between high and low, between eternity and workdays-not even history-between myth and chronicle, which have been found in art since the ’60s. The screen images refer to Roy Lichtenstein and others.

Luchezar Boyadjiev’s self-portrait with nails in his mouth refers to the portrait photograph of Pearls (in the mouth) subtitled “Sabine.”(Portraits. Peter Weiermair, ed., The Portrait in Contemporary Photography (Zürich/Kilchberg: Edition Stemmle, 1994). “Pearls (Sabine),” 1986. The Photographer is Erwin Olaf.) And yet I would rather perceive the concrete aspects of the work in order to check if it is not something different, despite the known devices, to see if Boyadjiev does not “quote” deliberately.

I think my attitude should be openness to interaction, and even-let me use this word-to the determination to achieve the unique concreteness without pretending to be an art critic or master of knowledge. To stick to the concrete seems really difficult.

There are two opposite roads from here. The piece of art does not stand the test of my commitment as a viewer, but instead turns out not to be quoting or imitation in another context, but a deceit. Its goal has not been an aesthetic object or practice, but their instrumentalization: some kind of adjustment to extra-artistical expectations, social conformity, demonstration of exhibition activity, art marketing strategy, and media coverage.

The second road is more attractive: The impact of the work (conception, form, materials) transforms the initial openness of the viewer into interaction and, finally, into an aesthetic event.

The peculiar aspect now is that, after the end of modernity, the institution of art is not sufficient to legitimize a work (conventional or not) as art; the exhibition space is not a good enough determinant, and the notion of art changes with almost every piece of art.

So, it is impossible to draft a common notion of art because of the intertwining and mixing of artistic activities with other kinds of social activity. All of that interaction requires the engagement of the viewer to legitimize a certain form or action as art, as an aesthetic practice.

Let me go back to Luchezar Boyadjiev’s installation. He would not be a conceptualist had he not tried various techniques of composition and impact. Far from the computer-graphic exhibit, in another part of the hall, is a crucifix with its back to the graphic work and to the viewer.

Through it, the space of the installation becomes also a space of the viewer, who is introduced to the action and turn to a potential participant.

Just that crucifix could orient us to the interpretation of a religious topic, to the search for the wonder in common everyday life, to the punishment and expulsion of Jesus Christ from . . . where?

I think that the supposition for the punishment of God, imposed by humans, would be an overinterpretation, and the supposition that religion is expelled from modern times is banal and hardly the message of that installation.

Following that religious direction, I would rather stay with what I have seen: Jesus Christ has turned his back to me, he is far away, and he looks small and haggard.

In another variant of the installation, the crucifix is put on a table with a lace tablecloth. I like that idea more. Christ is in the house, though we have our backs to him. We have forsaken him and, along with that, we have forsaken values the existence of we might not even have known.

I can ask myself if God could forsake man and what that means exactly or if God exists for man only in their mutual, interactive being. Based on those personal reflections, the lace tablecloth must function as an image of the seeming coziness of things, despite the fact that the dimension of the temple is missing.

If thetable had been put in the gallery, the passing from one part of the gallery into the other would have meant moving from the street to the home and vice versa. Because of the concrete dimensions of the space, I would have felt more like a participant, whereas now I feel like an observer.

Upon entering the gallery, the viewer faces the video screen where he sees a parrot and hears parts of words, stuttering, something like a conversation between God and the bouncing parrot.

An invisible voice is pronouncing some pieces of information in different languages and the parrot is repeating them without learning or even understanding a word.

The viewer hears this “conversation” all the time while orienting himself in the other two parts of the installation, because the voice of God and its echo in the parrot’s voice continue for an hour and a half. Obviously, the text version is shortened less than the pictorial one.

Listening to the voices coming from the monitor, I begin perceiving the installation as a combination of absurd elements. The main questions become whether there is a religious commitment behind Luchezar Boyadjiev’s treatment of that topic (cf. for instance his work “Modern Golgotha,” 1994), and why he uses basic events and symbols of Christianity as his topics if there is no such commitment. His purpose is obviously not any atheistic propaganda, nor is there any condemnation of Christianity. Why should an irreligious message be expressed by religious images and topics?

I would like to see a vision of the world in the installation, but what I can see is a refusal of it, an impossibility to establish order, and instead, emptiness and confusion and their multiple reproductions with no way out.

This refusal explains the author’s wish to repeat the computer graphics presented as video installation in a ping-pong effect for ten or fifteen minutes, as well as the infinity of the echo, deprived of any sense, with this parrot’s voice which could be the voice of the world. The title-Updated Gospel-short (cover) version is included in that deliberate lack of meaning.

I wonder if Boyadjiev refers to religion as something nonexistent only because he looks upon it as part of a culture whose horizons are the clichés; perhaps, on the contrary, religion, though part of the culture of the mass media and the comics, could give another dimension to the same culture and transform it.

In Eye-Cross which is part of the exhibition titled “In Search for the Self-Reflection” (Plovdiv, Bulgaria, 1994), the cross is used as a metaphor of looking into oneself. In Pulpit-Cross, the cross is a high place for the public voicing of the self.

The quick identification of religious signs in Luchezar Boyadjiev’s projects is telling because there exists a refusal of the signs; they are nonspecific carriers of other ideas. In the spatial correlation of “here” and “there,” which is also a correlation of values, his projects remain here. The clearest expression of that is the project Neo-Golgotha.

The tension, originating between the traditional, slow technology of casting the bronze crucifix and the modern computer design of the graphic work, is left out of the viewer’s perception.

I ask myself if the crucifix would give a different idea of perception had it been made more tangible in terms of size and weight which could have mastered the space-that is, the tangible weight of Christ’s absence from home, the absence of love, kindness, and compassion, the absence of Otherness.

Inmy view, if the graphic work, in its own comic genre, was made in a more sophisticated way, then it would have introduced the dimension of metaphysical otherness to each banal experience as well as to the comic representation.

This, I presume, is because an existential and metaphysical yearning is hidden even in the most banal experience. But what is a common aspect of conceptual art is the partiality for the conception at the expense of form.

I venture that the basic suggestion of the religious installations of Luchezar Boyadjiev refers to the spoiled metaphysical aspect of the comics, to the artist’s awareness of the possible banality of metaphysics, of which he is not convinced or does not allow himself to believe that the transcendence is possible.(Especially Fortification of Faith, 1991, and Luchezar Boyadjiev’s thoughts on John the Baptist (Catalogue, ifa-Galerie [Stuttgart: ifa-Galerie, 1991] 16).)

In April 1997 in Ata-Ray gallery, Nadezhda Lyahova presented the exhibition “Variants.” Sometimes the titles that artists give to their works are not adequate to the significance of the work. Here, for instance, I cannot see variants. What I see instead is the idea of a world integrating home and temple in a unified space. The space is filled with cutlery arranged in such a way as to present the following:

a) altar space-fork and spoon in a white frame, raised high above the viewer’s glance;

b) the cutlery has left its imprint (almost human body-like contours) on volumes looking like cult buildings which could be temples or tombs;

c) the roof from which the cutlery is hanging on thin threads.

If the viewers decide to come in under the roof and move the cutlery around, they will hear bell sounds whose melody will envelop and protect them from the outside world. The space is so unified and harmonized that the question of the correlation between “here” and “there” (reality and transcendence) does not arise.

The home is seen as built of light and sound, transcended in the direction of a longing for being together: a space of dreams. The cutlery is not so much cutlery as it is a source of light or sound-or, simply, whiteness.

The imprints of the cutlery and their light sound are impressions of a sublime corporeality. This becomes even clearer in Lyahova’s watercolor Food(“Bulgarian Art Book” Exhibition Catalogue May 1997, Ata Gallery, Sofia. I suppose that the word “Bulgarian” related to an art book marks only the passport identification of the participants.) in which the food is absent. The contours of utensils and cutlery vanish and melt instead on a background that also vanishes and melts away.

For both exhibitions, the key idea would be “food,” transformed into another food by its very material absence. Undoubtedly, the impact and the delight of the reproduced page in the exhibition catalog “Bulgarian art book”(“Bulgarian Art Book,” Exhibition Catalogue January 1998, Sofia (Bulgarian and English).) are emphasized by the flatness of the plate, of which only an insecure oval is left against the vertical line of the knife.

“Variants” is a space for intimate religiousness, homage to a home altar, combining simultaneously the metaphysical bases of the home and the real ones of the temple. I would rather not ask myself whether “Variants” refers to historical traditions of representation or uses religion as its topic. It is enough that the exhibition offers space for experiencing everyday things as transcendent.

In her review of the exhibition, Yaroslava Boubnova spoke with approval about “escapist aestheticism.”(Yaroslava Boubnova, “Nadezhda Lyahova’s Exhibition ‘Variants,'” Kultura Weekly, 4 April 1997, 12.) In a way, it is true that conceptual assemblage, driving the public into itself, focuses on an unbearable outside (personal or social) reality through negation.

The awareness of the impossibility of merging of “here” and “there” is committed to the public. Through the demonstrative dematerializing of cutlery and its imprints, it becomes painfully clear that the home and the temple are two separated spaces whose merger is a dream only possible for a short time within the realm of the aesthetic.

This essay was presented as a paper to the conference “Ars ex Natio. Made in Bulgaria,” June 1997, Plovdiv, Bulgaria. The conference was part of Visual Arts Program, Fourth Annual Exhibition Plovdiv-Old Town, Soros Center for the Arts-Sofia. It was enlarged for the publication in the catalog of the exhibition “Ars ex Natio. Made in Bulgaria” with the texts of the attendant conference, Sofia 1999. For this publication the essay has been slightly abridged. It was translated by Sylvia Golemanova and corrected by the author.