Calling the Dead in Budapest: Ágnes Eperjesi on Art, Women, Power and Violence

In 2018, on an October evening, the Hungarian National Gallery became the site of unusual activities: the artist Ágnes Eperjesi appeared in Cupola Hall of the building that was once the Royal Castle to ceremoniously cover the bronze cast of a naked girl. The life-sized sculpture, made of two unattached bronze shells by artist Gyula Pauer (1941–2012), represents seventeen-year-old Csilla Molnár (1969–1986) who won the country’s first postwar beauty pageant in 1985. One of the most publicized events of 1980s Hungary, attracting more than two thousand contestants, the pageant was broadcast on television for the viewing pleasure of millions and became the subject of the award-winning 1987 documentary film, Pretty Girls.(Szépleányok, directed by András Dér and László Hartai (1987, Budapest: Balázs Béla Studio). The film received critical claim and became the most popular movie in late 1980s Hungary: it won best picture at the XIX. Hungarian Film Festival, received the jury’s special prize at the Mannheim Film Festival, and was voted “Film of the Year” by the Hungarian audience. http://www.molnarcsilla.hu/filmek/szepleanyok.htm; http://bbsarchiv.hu/en/movie/pretty-girls-433, accessed February 2020.) The contest popularized notions such as “choice,” “beauty,” and “queen,” which were unfamiliar in a country allegedly governed by Socialist mores, where the mediatized beauty industry and the mention of monarchs was thought to belong to the past and decaying capitalism. Organized by Hungarian Media, a state company, the beauty contest was not only portrayed in the media as a rare and titillating opportunity to see a parade of young women in bikinis, but also as a victorious step in the country’s long-awaited catching up with the West. As it later turned out, the contest’s primary purpose was to promote an Austrian tobacco brand.(The history and the media reception of the event have been discussed in Szépséghibák, the privately published book by Ferenc Gazsó L. and Miklós Zelei (Budapest, 1986), in Sándor Friderikusz’s reportage book, God Save the Queen (Budapest, Szendrő, 1987), in the documentary film, Szépleányok, and more recently, in the article, Zsófia Eszter Tóth and András Murai, “Szépek és szörnyetegek. Egy esemény emlékezete: Az 1985-ös szépségverseny, Korunk, 23. Vol. no. 12 (2012): 63-71.)

Ágnes Eperjesi. You Should Feel Honored, 2018. Performance, duration 30 min. Courtesy of acb Gallery, Budapest. Image courtesy of the artist. Photograph by Andrea Bényi.

The beauty queen’s life-cast was created as part of a so-called “Beauty Action,” conceived and orchestrated by Pauer, a critically acclaimed, but officially barely tolerated figure of the Hungarian neo-avant-garde art scene. Taking the opportunity to become part of the event and thus to publicize both his existence and work, Pauer offered to cast the naked bodies of the queen and the two runner-ups, thus transforming them into works of art to document both the event and contemporaneous notions of beauty. The artist’s gift-cum-self-promotion was announced during the coronation ceremony as part of the humiliatingly measly prizes and official awards that also included the gift parcel of a meat processing company. The life-casting, made into a mandatory activity by a contract signed between the artist and Hungarian Media, involved full-frontal nudity, heavy layers of gauze soaked in wet plaster, and the wandering hands of male assistants over female bodies in the artist’s studio. Cameras were also present: the process was shot by the documentary film crew who followed every stage of the pageant as well as by two young Hungarian male photographers who later, and without the models’ permission, but with Pauer’s consent, sold the pictures of the two runner-ups to the German-language edition of the soft-porn magazine Lui. The photographs showed the unsuspecting women under the headline, “Free yourselves, comrades!” in the magazine’s January 1986 issue.

Csilla Molnár’s nude casting shots were not published, but winning Socialist Hungary’s first beauty pageant quickly turned into her worst nightmare. Treated as the property of Hungarian Media, Molnár was subjected to abuse and mistreatment. In a country supposedly governed by Socialist mores, neither she nor her family was prepared to handle the exploitative media offers and suspicious invitations of various men to partake in exotic vacations and nude photo shoots. In the summer of 1986, less than a year after her coronation, Molnár killed herself: her premature death instigated extensive media coverage, and the ghostly cast that Pauer and his assistants took of her naked body became a commemorative work, an effigy of the dead.

A tale about the beauty and the beasts, Molnár’s story portrays an episode of the last days of goulash communism and the arrival of late capitalism with its promotional devices and mass-media frenzy. The debacle of the state-socialist pageant and the sad fate of Hungary’s first postwar beauty queen halted Pauer’s work on the sculpture and the organization of similar contests for years, and have been almost forgotten in the fervor that surrounded the political changes. The bronze version of the sculpture, The Beauty of Hungary, 1985, was completed a decade after the casting session, and in 1996, it was donated by the artist to the Hungarian National Gallery where during the last few years it stood half-abandoned in an office corridor.

Eperjesi’s work on the beauty pageant and Pauer was motivated by her interest in the sculpture as well as by the global spread of the Me Too Movement. She has been addressing issues of gender and politics, the social constructedness of the image, and the phenomenology of visual perception since the 1990s. In her installations and photo-based works she often appropriates images and objects—pictograms of commercial articles and family photographs—to reflect on issues of domesticity, gender and everyday life. By using processes such as repetition, enlargement, quoting and recycling, and by relying on theories of vision and color perception, Eperjesi negotiates the relationship of original, copy, and simulacra, and models how images and objects preserve and, at the same time, cancel collective memory. Since the early 2000s, she has also been working in performance, labelling her politically informed public pieces and videos as “protests.”(For an overview of Eperjesi’s work, see the artist’s website http://www.eperjesi.hu/ (accessed February 2020)) In 2018 Eperjesi launched an extensive research project that explored the visual culture of Hungary during the Kádár regime, depictions of women and female nudity in the media, and the critical reception of Pauer’s work. She investigated the history of the pageant; studied socialist censorship laws and regulations regarding nudity; collected calendar cards, magazines, and advertisements featuring lightly clad young women; and conceived a series of works, including the performance, You Should Feel Honored. The title referred to Pauer’s and the pageant organizers’ words that had reminded the models of the privilege to be touched against their will.

In October 2018, thirty-three years after the beauty queen’s coronation, Eperjesi was standing in the red marble interior of the Hungarian National Gallery next to Pauer’s bronze sculpture to evoke spirits and clothe the naked dead. Dressed in a white lab coat, similar to the one Pauer had worn during the casting process, she covered the bronze sculpture that was brought to the floor for a guided tour with a fifteen-meter-long red drape, then stitched the letters of the performance’s title to the fabric. The ritual veiling took place without an audience and after lengthy negotiations with the staff of an institution that is now annexed to the Museum of Fine Arts, the cultural conglomerate of the recently de-democratized country.(The artist and Kata Oltai, curator and founder of the feminist gallery FERi, first approached the Hungarian National Gallery in early 2018 with the project. After an extensive period of discussions, their proposal to engage Pauer’s work in a public performance was repeatedly postponed.) Like the pain and embarrassment suffered by the sculpture’s model, Eperjesi’s performance was a silent affair witnessed by only a few, and documented in a series of color photographs. By draping the naked body with a fabric reminiscent of the red carpet of photo shoots and fashion shows, Eperjesi sought to provide a fitting, mantle-like garment for the dead beauty queen that, at the same time, also appeared to be a restraining device and a burden.(For Eperjesi’s text see http://www.eperjesi.hu/protest/erezze-megtiszteltetesnek-feel-honoured?id=251 (accessed January 2020).) The reconciliatory dress-up was a gesture of care and an honoring of the dead, a healing ritual between women inviting viewers to think of Pauer’s effigy of Csilla Molnár as both a tomb sculpture and a document of abuse.

In May 2019, a few months after the performance, Eperjesi staged a second act by organizing a two-part exhibition at the Fészek Gallery in Budapest and publishing the essay “Private Interest and Public Treasure,” which charted her exploration of socialist body politics, Pauer’s sculpture, and the pageant’s history.(Ágnes Eperjesi, “Private Interest and Public Treasure 1-2,” punkt (2019), https://punkt.hu/en/2019/05/20/private-interest-and-public-treasure-1/; https://punkt.hu/en/2019/05/30/private-interest-and-public-treasure-2/ (accessed January 2020).) The show’s first section comprised the documentation of her performance, including the display of the red drapery with the phrase “You Should Feel Honored,” and a wide array of visual materials related to her research. She exhibited some of the early reviews of Pauer’s sculpture and its catalog card from the Hungarian National Gallery along the photographs of the casting published in Lui magazine. The documentary, archival section also included pages from journalist Sándor Friderikusz’s reportage book, God Save the Queen (1987), that contained interviews with the witnesses of Molnár’s life and death, and the manuscript of the letter by László Hartai, a director of Pretty Girls, written to Pauer in 1987, after the film’s release. In the letter, Hartai explained the rationale for the cinematic presentation of the life-casting and the dubious physical contact it entailed, while aiming to address Pauer’s concerns about being implicated in the exploitation of the women.

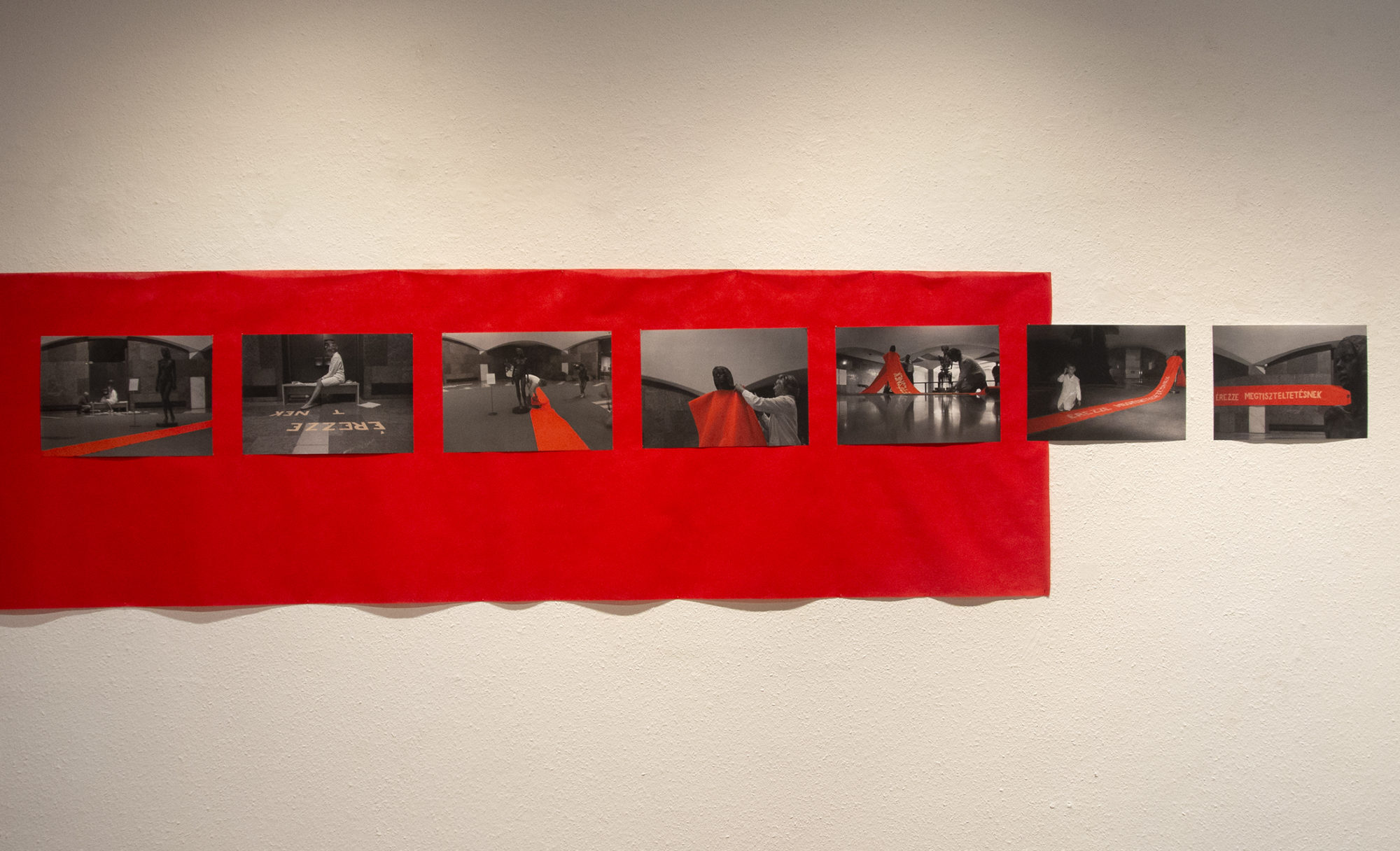

Ágnes Eperjesi. You Should Feel Honored, 2018. Mixed-media installation. Courtesy of acb Gallery, Budapest. Image courtesy of the artist. Photograph by David Biro.

The second part of Eperjesi’s exhibition, the installation Pathos and Critique, was presented in a separate, circular chamber of the Fészek Gallery. In contrast to the archival, printed ephemera that lined the walls in smallish frames in the first section, the installation, albeit barren, was a spectacular affair. Pathos and Critique consisted of a flaming red 3D printed copy of the head of Pauer’s sculpture and a metal scaffolding functioning as a body substitute that Eperjesi placed in the middle of the otherwise empty, white-walled and theatrically lit space. The fiery head and its base cast elongated shadows on the floor lending the already striking sculptural ensemble an even more pronounced aura and otherworldly effect.(Eperjesi has been exploring replication processes and shadows as working conditions, devices and metaphors since the early 1990s in her photo-based installations, re-photography projects, photograms, and most recently, in the essay, Expanded Photogram, cf. Ágnes Eperjesi, Early Photographic Works, 1986-1999 (Budapest: acb ResearchLab, 2019), 6-19.) Simultaneously compelling and disturbing, the red plastic sculpture produced affect by means of its subject, but also through its formal features. The facial expression of the closed-eyed, gently tilted effigy of the young woman’s head suggests a mute pain that is further accentuated by the inherent violence of the object—the uncanny red glow of the severed head is not only striking, but it also triggers retinal aggression. Staged as an installation, Eperjesi’s work is a spectacle of suffering that evokes such disparate artworks as antique sculptural fragments, Warhol’s garish and decapitated Marilyn (another woman turned into a floating sign of eroticized suffering), and the tortured beauty of Louise Bourgeois’s floating and vaulted bodies in her Arch of Hysteria series.

Ágnes Eperjesi. Pathos and Critique, 2019. 3D print and steel frame, 180 x 40 x 40 cm. Courtesy of acb Gallery, Budapest. Image courtesy of the artist. Photograph by David Biro.

By adopting Pauer’s bronze sculpture and titling it Pathos and Critique, Eperjesi expanded on her critical practice of appropriation, her ongoing interest in the circulation and replication of images, objects, and contexts, and on her works of political protest. The red plastic head recalls her series of recycled images that include commercial wrappers and family photographs, as well as her earlier photograms and photogram-based installations. The digitally photographed and printed copy of the head is a re-effigy that both reclaims and cancels Pauer’s bronze sculpture, and by extension, the plaster cast taken of Molnár. Pathos and Critique also points to the repetitive cyclicality and the serial nature of casting, and brings into play issues of authorship and ownership that exist in the practice of mimetic replication by asking viewers to consider whose cast they are seeing—Molnár’s, Pauer’s or Eperjesi’s.

The title of the installation reflects on the reception of Pauer’s sculpture, as pathos and its synonyms often appear in the critical literature about The Beauty of Hungary, 1985–1995. Since its origins in Attic drama, pathos is understood in relation to suffering and tragedy: whether it is an event, or a rhetorical, or visual topoi, pathos solicits emotions and affect, compassion and empathy. Responding to the first version of the sculpture in 1987, the critic Éva Körner wrote about the “cathartic experience” of the frozen female body that “subverts customary modes of seeing,” adding that “the heroism which can only be conveyed by the magic of a motionless figure” also undermines “the voyeuristic gaze.”(Éva Körner, “Az absztrakt és konkrét szobrász: PauerGyula,” Filmvilág 30, no. 5 (1987):25.) In a review of Pauer’s 2005 retrospective exhibition at the Budapest Műcsarnok, critic Géza Perneczky who, before leaving Hungary in the 1970s for Cologne, belonged to the inner circles of the Hungarian neo-avant-garde, described the work as “unforgettable and enigmatic, since victimhood wraps it in a transcendental light.”(Géza Perneczky, “Héj és lepel,” Holmi (July 2006):968.) While Körner insists on the emotional appeal of the body cast disregarding its model and making, Perneczky relates the poignancy of the sculpture to the sad fate of the model—as different as they are, none of these accounts take into consideration the political context and the ethical dimensions of the work.

Ágnes Eperjesi. Pathos and Critique, 2019. 3D print. Courtesy of acb Gallery, Budapest. Image courtesy of the artist. Photograph by David Biro.

The life-casting of a naked body is always already an eroticized process, but in the case of Molnár and the beauty contest’s runner-ups, the exploitative power dynamic between female models and male sculptor was even more obvious, as the young women, obligated to feel honored, could not refuse to be subjugated to the act. The process demonstrates the disciplinary practices of modern bodies and the exploitative sexual politics that governed the relationship between male artist and female models with mortifying clarity. Obeying the order of the company Hungarian Media and covered with gauze and wet plaster, Molnár and her peers became docile bodies, subjected to powers similar to those processes that according to Michel Foucault were at work in the making of soldiers in the 18th century. The young women became “something that can be made; out of a formless clay […] a calculated constraint runs slowly through each part of the body, mastering it, making it pliable.”(Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Vintage, 1995 [1977], 135-136.) The casting and negotiations among men, the artist, his crew, the photographers and the documentary filmmakers, were recorded in Pretty Girls and also dealt with in Friderikusz’s book about Molnár. What took place in Pauer’s studio was a textbook case of the subjugation and coercive instrumentalization of the models’ body.

As the artist recalled in a conversation with István Antal in 1993, the public opinion shaped by widely published articles in the Hungarian media considered him partially responsible for and complicit in Molnár’s death, portraying him as a “satyr.”(István Antal, “Az álcázott látszat. Pauer Gyulával beszélget Antal István, Magyar Napló (July 9, 1993): 15–17.) Despite this dubious fame, Pauer’s responsibility for abusing the models whose suffering was literally imprinted on the bronze sculpture of the beauty queen is omitted from the critical accounts of his work. Annamária Szőke is the only author who considers the ethical implications of the procedure in her cogent analysis of the artist’s “beauty casts.”(AnnamáriaSzőke, “Szépségminták, héjplasztikák és fotószobrok,” in Pauer, ed. Annamária Szőke (Budapest: MTA Művészettörténeti Kutatóintézet, 2005), 235-249.)Generally understood as an emotive meditation on beauty, The Beauty of Hungary, 1985 was questioned neither for its abuse of women nor for its retrograde esthetic that borders on kitsch, as these considerations would have clearly undermined Pauer’s canonical status as a progressive conceptual artist.

Similar to her performance, Eperjesi’s Pathos and Critique called on the dead: the installation provided a reenactment and a commentary on Pauer, the bronze sculpture and its interpretations as well as on the instrumentalization of the female body that made Csilla Molnár’s sculpture possible. By addressing the critical deficit of the literature, Eperjesi’s exhibition and installation also spoke to a gender-based revision of the neo-avant-garde canon and the uneven power relations of the Hungarian art scene.

A month after the opening of her exhibition, Eperjesi extended the field of her research and critical engagement by inviting artists, scholars, critics and curators to discuss the body politics of the Hungarian neo-avant-garde.(A neoavantgárd testpolitikája és utóhatásai, Fészek Művészklub, Budapest, June 2, 2019. For the video recording of the roundtable see https://www.facebook.com/fotoklikk/videos/2498910863669901/, accessed January 2020.) The roundtable addressed the fake veneer of gender neutrality that governed life under state-socialism in a country whose language is genderless and where—despite the prevalence of dual income families and equal employment—gender equality was nonexistent and women’s rights were rarely protected. The panelists also talked about the discursive deficit of the gender-related political and cultural manifestations of the Kádár-era, and pointed to the parallels between the heroic machismo of the political opposition and the dissident artists. The latter is especially instructive when considering the glaring lack of accountability and the missing discourse of power politics that Pauer and his work manifest.

In Soviet-era Hungary, the circles of the democratic opposition and the unofficial artists were both dominated by men who advocated for human rights and freedom of expression without considerations of gender equality. While the practice of the Hungarian neo-avant-garde artists was seen as oppositional and westernized—as Boris Groys wrote about Soviet art in the 1960s and 1970s, “unofficial art was considered to aesthetically represent the West at a time when political representation of Western positions and attitudes was impossible”(Boris Groys, “The Cold War between the Medium and the Message: Western Modernism vs. Socialist Realism,” e-flux Journal #104 (November 2019), https://www.e-flux.com/journal/104/297103/the-cold-war-between-the-medium-and-the-message-western-modernism-vs-socialist-realism/, accessed January, 2020.)—the gender disparity within the inner circles of dissenting artists and intellectuals shows the limits of this westernization. The absence of viable feminist organizations, a topic often mentioned by the participants of the roundtable, and the severely limited lack of visibility that women artists experienced reveal that the dissenting artists and intellectuals of the Kádár regime—like their enemies, the party bureaucrats—also operated through their masculine privilege and patriarchal authority.(About the lacking discourse on women’s emancipation among the members of the political opposition in Hungary, see Judit Acsády, “Megtettük-e azt, amit az eszményeink szerint meg kellett volna, hogy tegyünk? Az államszocializmus demokratikus ellenzékének elmaradt nőemancipáció-reflexióiról,” Socio.hu: Társadalomtudományi Szemle 2 (2016): 175–197. https://socio.hu/uploads/files/2016_2/acsady.pdf, accessed February 2020.) The reluctance that characterized the dispositions of Sovietized Hungary’s nonconformist politicians and artists toward their fellow women can be explained as a form of resistance to the official, governmental advocacy for women’s rights. By opposing the doubtlessly spurious rhetoric that characterized state socialist policies on the women question and thus refusing to honor ideas and practices of gender equality among themselves, the circle of radical artists mirrored the patriarchal structure of Socialist Hungary—it was a world governed by the unquestioned authority of men. By bringing Pauer and his work to the attention of contemporary viewers, Eperjesi made visible the heroic cult and masculine mythology that permeated the circles of Hungarian counterculture, and still dominates the discourse on art in the country. In today’s post-socialist Hungary, the belated and often market-driven canonization of formerly dissenting artists, with the exception of Dóra Maurer, is limited to male artists, and the gender inequalities of the Kádár-era art world have yet to be addressed by the historians of the period.

While the speakers of the roundtable explored a wide-array of topics spanning decades and various fields of inquiry, the issue of contemporary Hungary and its gender equality policies, or lack thereof, was suspiciously absent. Created in response to rise of the Me Too Movement, Eperjesi’s multi-layered project—her performance, research, the two part exhibition, and the roundtable discussion she organized—proposed a critical engagement not only with the past, but also with the present. “A manifesto and an analysis,” as art historian Emese Révész suggested,(Emese Révész, “Az aktmodell mint munkatárgy,” Új Művészet (July 2019): 59-61.) it compelled its viewers to realize that Csilla Molnár’s death and her exploitation during and in the wake of the pageant was not a transitional occurrence, the unavoidable growing pain of the political and economic changes that lead to the collapse of the Soviet-era, but an uncanny foregrounding of what was yet to come.

As Joanna Goven repeatedly argued, the practice of “civic antifeminism,” a characteristic feature of social relations among the members’ of Kádár-era opposition, was carried over seamlessly into the political arena and private sphere of post-socialist Hungary.(Joanna Goven, “New Parliament, Old Discourse? The Parental Leave Debate in Hungary,” in Susan Gal and Gail Kligman. eds.,Reproducing Gender: Politics, Publics, and Everyday Life after Socialism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000), 286-306.) Although masculine dominance is no longer exercised by the bureaucrats of state-socialism but by the representatives of the semi-feudal new order of the Orbán government, the patriarchal power structure remained unchallenged. In contrast to the Socialist policies that degendered and thus depoliticized women in the workforce and the sphere of art and cultural production, processes of feminization and regendering are cornerstones of the reigning conservative regime. From the repression of state-socialism to that of authoritarian populism, gender inequality has remained unchallenged: women, whether artists, mid-level employees and managers or laborers, along with ethnic minorities such as the Roma and refugees, were and still are the main targets of subordination and discriminatory policies.

Since the early 2010s and the rise of the conservative populist Orbán regime, “civic antifeminism” not only subsisted, but became a dominant feature of the new order that is characterized by a flagrant lack of legislations granting and protecting gender rights and minorities. The European Institute for Gender Equality’s data indicate a steep decline in the equality of gender rights.(European Institute for Gender Equality, Gender Equality Index 2019: Hungary, https://eige.europa.eu/publications/gender-equality-index-2019-hungary, accessed January 2020.) Hungary now is a country where men practice libidio dominadi unquestioned and without systems of control. While the gender-based disparity exists in every facet of society, including wages and division of labor as well as in the field of politics and scientific research, the most obvious sign of the country’s deeply ingrained patriarchal structure is the refusal to protect the human rights of women. According to data gathered by the local not-for-profit organizations, NANE Women’s Rights Association and Patent Association (Society against Patriarchy), between November 2017 and June 2018 twenty-seven women were killed by their current or former partners (https://nokjoga.hu/alapinformaciok/statisztikak, accessed January 2020). While domestic violence has reached nearly epidemic proportions, the Hungarian government refuses to ratify the Istanbul Convention, the European Union’s treaty to prevent and combat domestic violence and violence against women.

By prompting questions about gender, power, and violence, Eperjesi’s work forges a trans-temporal connection between the late Kádár regime and contemporary Hungary. The installation and the multi-part work You Should Feel Honored commemorated Molnár, the history of her sculpture and the country where she lived and died, claiming that, as Walter Benjamin wrote in his essay on Proust, “a remembered event is infinite.”(Walter Benjamin, “On the Image of Proust,” in Selected Writings, Vol. 2, Part 1, 1927–1930, ed. Michael W. Jennings et al. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2005), 238.) Eperjesi’s veiling and unveiling, dressing, and addressing of the dead woman’s sculpture and the many histories evoked by her demise is an act of reparation and a manifestation of solidarity, yet it is more than a restorative gesture of archive fever wishing to remedy the traumas of the past. You Should Feel Honored is also a study of the power mechanism of subjugation and the violence against women in early 21st century Hungary. Guided by a desire to chart the archeology of gender disparity and abuses of power, the performance and two-fold exhibition is a multilayered critique aimed at the Hungarian National Gallery whose curators were reluctant to cooperate with the artist, art historians, and writers who failed to address Pauer’s work and its body politics, and at the missing discourse and awareness of gender inequality in Hungarian society. A sharp statement and a passionate solicitation, You Should Feel Honored is a rare instance of critically engaged art that moves and provokes us, and by imprinting the flaming red head of the long-dead woman on our minds, it haunts us forever.