Boris Orlov: The Story of an Imperial Artist

Moscow Museum of Modern Art, Ermolaevsky pereulok, February 14, 2008 – March 16, 2008.

The exhibition of the Russian sculptor Boris Orlov, held last March, initiated a survey of unofficial Russian art and its key individuals – a period that is currently in focus in the context of increasingly market-driven art practices.

The retrospective, entitled Earthly and Heavenly Warriors and sprawling over four floors of the Moscow Museum of Modern Art [MOMMA], numbered about 80 sculptures in all. Orlov’s subjects are the Soviet ruling elite that he has rendered in a stylized and idiosyncratic manner, either carved as busts, portrait reliefs or sculptural installations. The torsos of varying sizes are in full regalia and embellished by medals, honors and elaborate epaulets. Painted in primary colors and crafted from wood, porcelain or bronze, the sculptures were over life size, once they had been positioned on freestanding plinths. The reliefs attached to the walls extended horizontally in a sequence akin to archaic totems. Covered by enamel – shiny and bright, these immobile symbols conjure up the atmosphere of celebrations that were so prominently featured on Soviet television. A grotesque parade of “immortal” heroes marches through the floors of the museum.

Orlov, the key artist of Moscow’s unofficial circle, has been concerned for the past 40 years with the representations of power. Now in his mid 60s the artist recollects: “The subject of Soviet state power it was forbidden to critique: by portraying its top echelon I crossed out my official career as an artist forever.”(In conversation with the artist, Orlov’s studio, Moscow, May 2008.)

As early as the1970s Orlov sculpted gods of antiquity such as Icarus (1970) and Phoenix (1971) in terracotta or plaster. These symbols of the modern man, one who flew too close to the sun and the other who came back to life after death, illustrate the artist’s erstwhile interest in metaphysics. This was the artist’s response to the contemporary system of rigid axioms that had been established by the Soviet ruling elite in an attempt to control the minds of its citizens. As a form of resistance, non-official philosophies sprung up within multiple branches of intellectual thought, ranging from Marxism to Structuralism and metaphysics. For Orlov and many other intellectuals, philosophy was an act of self-liberation acheived through the awareness of subjectivity of the dominant ideology. As a result his early and rarely seen sculptures only hint at the connection between fallen heroes and the Soviet Utopia. Icarus symbolizes those Soviet intellectuals who were burnt by Utopian ideology. These terracotta or plaster busts were displayed on the top floor of the museum and, depending on where the viewer started his journey they either initiated or wrapped up the artist’s retrospective. (The Hellenic heroes brought to mind a focus on material exuberance and a reference to the mighty Roman Empire implicitly juxtaposed with the Soviet state.)

By 1975 the artist had turned his creative mind toward the “modern gods” that were conceived by the Soviet propaganda. Brezhnev and the other Fathers of the State assembled a modern pantheon as Russia was entering the Cold War, rekindling Russia’s former imperial ambitions. Orlov sculpts the players of the ruling elite in his “Official Portraits,” accentuating the key elements of their power. The medallions and ribbons as symbols of social and political hierarchy adorn the chests of the abstracted busts. Sometimes, there is just not enough room to fit them all. In that case, Orlov extends the width of the torso so the sculpture takes on the shape of a horizontal slab. When confronted by the sculptures the viewer is able to understand the clues: the artist mocks the heraldic symbols of the phony Soviet officials.

Orlov, like the other unofficial artists and his contemporaries – Ilya Kabakov, Dmitry Prigov, and Leonid Sokov – depicted Soviet reality in a highly idiosyncratic way. Cleverly using the language of the official Soviet ideology, Orlov takes it out of context and twists it into sarcastic quotations. For example, Orlov makes the heads of the busts disproportionately small, as if they are unimportant and lacking in individuality. In sculptures such as Official Parsuna (1982) and Totem (1986), the ribbons of honor take on a life of their own animated by the contrast of imperial colors – red, blue and black. Crafted in a carnival-like mode, the pieces hearken back to the genre of painted sculptures that has been an important part of Russian folk and decorative art. In this way Orlov’s subjects outgrow temporal connections and become symbols of any state power with imperial ambitions.

The artist’s satirical vision culminates on the 3rd floor of the museum with an unforgettable installation. The sudden change is astounding. Orlov shifts from the vertical, brightly colored figures to horizontal dynamics and forces the viewer to look up Just below the ceiling is a cluster of bird-like black creatures that rush forward. This constellation titled Parade of Astral Bodies (1994) is a collection of sculptural hybrids: heads of German eagles and tails of Soviet airplanes covered with black cloth. These phantom missiles are symbols of dominion and death, pouring out of a replica of Kazimir Malevich’s painting, “Black Square,” which is hung on the wall. This “Black Square” is emblematic of modernism and the Russian avant-garde, and at the same time stands for the many crimes that modernity perpetrated under the Fascist and Soviet empires. The whole space is painted black and filled with sounds of a symphony by the 19th Century Austrian composer Anton Bruckner. Parade of Astral Bodies illustrates the artist’s move away from the free-standing sculpture which began at the end of the 1980s.

The artist’s satirical vision culminates on the 3rd floor of the museum with an unforgettable installation. The sudden change is astounding. Orlov shifts from the vertical, brightly colored figures to horizontal dynamics and forces the viewer to look up Just below the ceiling is a cluster of bird-like black creatures that rush forward. This constellation titled Parade of Astral Bodies (1994) is a collection of sculptural hybrids: heads of German eagles and tails of Soviet airplanes covered with black cloth. These phantom missiles are symbols of dominion and death, pouring out of a replica of Kazimir Malevich’s painting, “Black Square,” which is hung on the wall. This “Black Square” is emblematic of modernism and the Russian avant-garde, and at the same time stands for the many crimes that modernity perpetrated under the Fascist and Soviet empires. The whole space is painted black and filled with sounds of a symphony by the 19th Century Austrian composer Anton Bruckner. Parade of Astral Bodies illustrates the artist’s move away from the free-standing sculpture which began at the end of the 1980s.

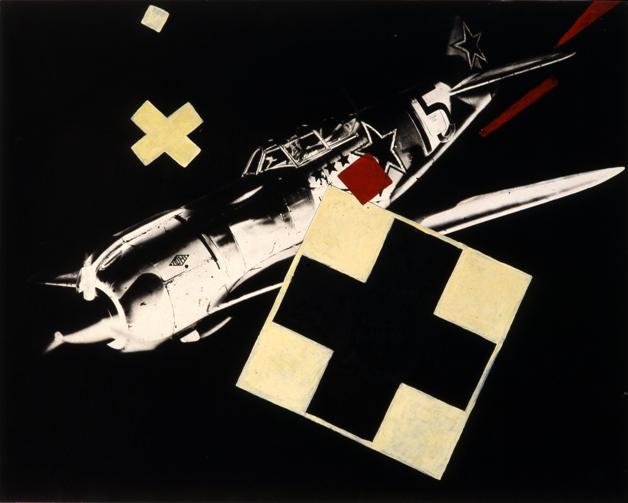

Orlov makes another statement about imperial ambitions in his installation Victory over the Sun (2002) – a modern vision of the famous 1913 opera sets created by Malevich. Orlov collages Malevich’s dynamic Suprematist compositions over the images of Nazi missiles. These photographs serve as a backdrop for two aircraft wings that have crashed into the ground, and illustrate what the artist sees as the destiny of all short-lived Utopias.

Orlov makes another statement about imperial ambitions in his installation Victory over the Sun (2002) – a modern vision of the famous 1913 opera sets created by Malevich. Orlov collages Malevich’s dynamic Suprematist compositions over the images of Nazi missiles. These photographs serve as a backdrop for two aircraft wings that have crashed into the ground, and illustrate what the artist sees as the destiny of all short-lived Utopias.

Overall, what ultimately sustains and propels this retrospective is the clash of two forces: celestial and subterranean. Installations like Parade of Astral Bodies and Victory over the Sun represent celestial forces, like, birds and airplanes. The vertical and freestanding sculptures represent warriors de terra: generals, sailors and athletes. The ultimate success of Orlov’s retrospective lies in this diverging juxtaposition.

The exhibition’s title is particularly apt, and was appropriated from an icon dating from the 16th century that featured the victory by Ivan the Terrible over Kazan in the mid fifteen-hundreds. From that very time Russia declared itself an empire, reaching from the Balkans to Chukotka, the furthermost point of the Russian Far East.

These imperial ambitions, which were conceived during Russia’s pagan beginnings and carried all the way through the Revolution and into the Soviet period permeated the motifs of Orlov’s sculptures. The totemic references to a pre-Christian goddess come alive in the works Saw (1979) and Bird (1983), and are followed up in the vigorous busts comprising In A Spirit Of Rastrelly (1988) culminating in the imperial emblems of the Soviet state.

These imperial ambitions, which were conceived during Russia’s pagan beginnings and carried all the way through the Revolution and into the Soviet period permeated the motifs of Orlov’s sculptures. The totemic references to a pre-Christian goddess come alive in the works Saw (1979) and Bird (1983), and are followed up in the vigorous busts comprising In A Spirit Of Rastrelly (1988) culminating in the imperial emblems of the Soviet state.

In 2008 the Soviet empire no longer exists, but Orlov’s works are still timely reminders. It may come as a surprise that the imperial ambitions continue to persevere, perpetuated by the current “democratic” State and its top echelon, so eloquently hinted at in Orlov’s exhibition. Perhaps these parallels were accidental, but they appeared deliberate in this exhibition, which aimed to historicize recent art tendencies.