Yevgeniy Fiks at Winkleman Gallery (Exhib. Review)

Yevgeniy Fiks, Ayn Rand in Illustrations, Winkleman Gallery, New York, June 18 – July 30, 2010

Over a long history, image and text have related in complicated ways. But one idea remains constant: that when placed in juxtaposition to each other, we expect important connections to be revealed.

Over a long history, image and text have related in complicated ways. But one idea remains constant: that when placed in juxtaposition to each other, we expect important connections to be revealed.

In his exhibition at the Winkleman Gallery, Ayn Rand in Illustrations, Yevgeniy Fiks adds another layer of complexity to this relationship; as an émigré from a former anti-capitalist state (the Soviet Union), he has decided to confront the work of one of the most vehement capitalist populists. The fact that Rand was born in Russia only adds another twist.

Fiks brings together excerpts from Rand’s novel Atlas Shrugged and the images he found in books printed in the Soviet Union. The artist said that he was drawing parallels between the monumental style of Socialist Realism and Rand’s aesthetics of Objectivism, both of which blossomed in the 1930s. The connections between the histories of Soviet Russia and America through the time of Cold War are central to Fiks’ work. Indeed, the artist claims he was “breast-fed” this officially approved Soviet style from his youth in Moscow. By 1992–the year he emigrated from Russia to the U.S.–Fiks took upon himself the task of tracing overlaps of Soviet Union and American histories.

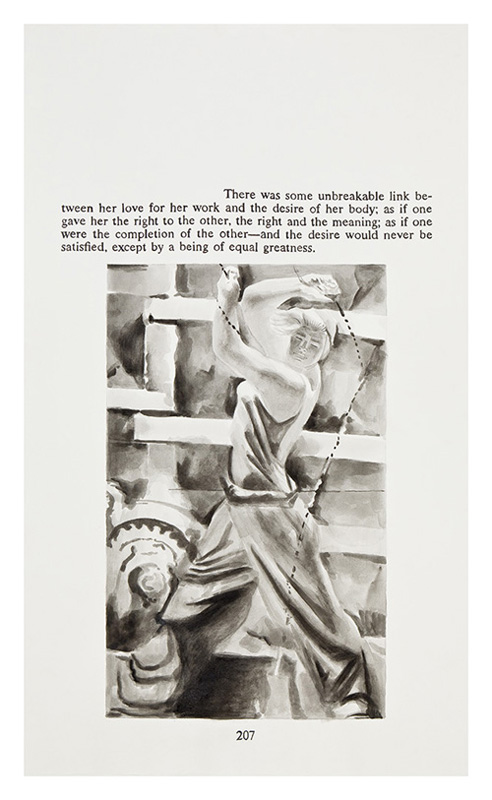

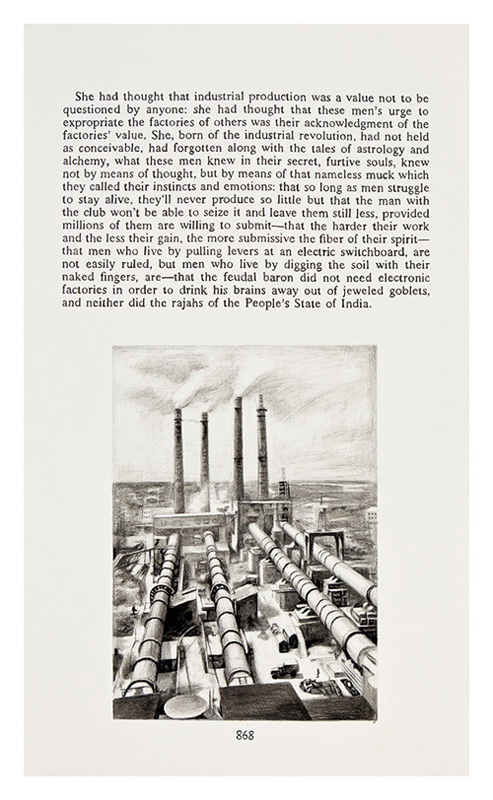

At first glance this is a very attractive exhibition, comprising a body of twenty-two identical (34’ x 76’) works on paper, all neatly held in black frames. Each sheet of paper carries an image which combines a drawing and a text; the image is dominant, taking up most of the page, while the texts are either short or long. Not all the images are centered, however, but rather float in relation to paper edges. Rendered in a variety of mediums from watercolor, to ink, to pencil, these graphic studies are assembled to correspond to pages of Rand’s book, with sheet numbers referring to the page of the quote’s origin in Atlas Shrugged. For many, this “bookish” format may be convincing, but it does not conceal the several arbitrary and simplistic combinations that both text and image produce.

At first glance this is a very attractive exhibition, comprising a body of twenty-two identical (34’ x 76’) works on paper, all neatly held in black frames. Each sheet of paper carries an image which combines a drawing and a text; the image is dominant, taking up most of the page, while the texts are either short or long. Not all the images are centered, however, but rather float in relation to paper edges. Rendered in a variety of mediums from watercolor, to ink, to pencil, these graphic studies are assembled to correspond to pages of Rand’s book, with sheet numbers referring to the page of the quote’s origin in Atlas Shrugged. For many, this “bookish” format may be convincing, but it does not conceal the several arbitrary and simplistic combinations that both text and image produce.

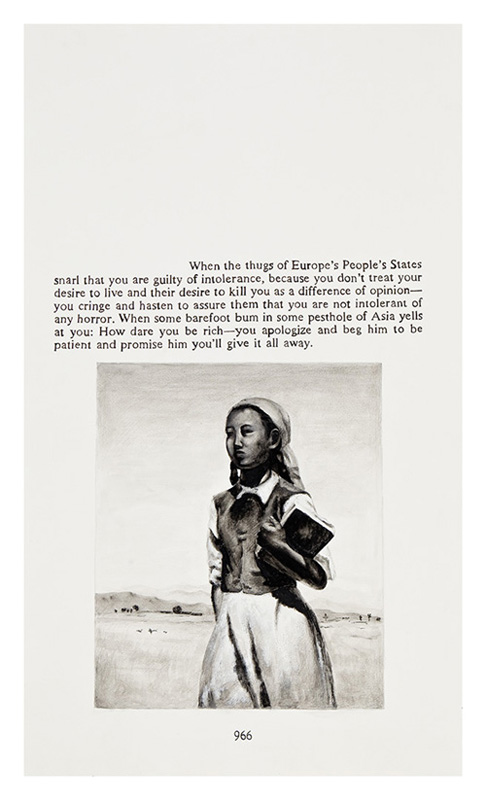

Overall, the texts included are moralistic, libertarian prose, praising industrialization and money. Phrases like, “We are the soul, of which railroads, copper mines, and oil wells are the body,” or “…he had no touch of that which people called culture. But he knew railroads” are illustrated by either scenes of monumental construction or tall, muscular people walking across landscapes of new development. In one particular piece, Fiks combines a quote about “some barefoot bum in some pesthole in Central Asia” with an image of a girl walking through a desolated, rural area while clenching books inher hands. Her head scarf frames her high cheek bones and almond-shaped eyes. Although these images are unknown to the Western viewer, the connection between Randian and Soviet ideologies is definitely not a new subject. (A quick internet search gives pages of materials which link Rand’s pro-right ideas with Stalinist propaganda, including the style of Socialist Realism as its visual manifestation.)

Overall, the texts included are moralistic, libertarian prose, praising industrialization and money. Phrases like, “We are the soul, of which railroads, copper mines, and oil wells are the body,” or “…he had no touch of that which people called culture. But he knew railroads” are illustrated by either scenes of monumental construction or tall, muscular people walking across landscapes of new development. In one particular piece, Fiks combines a quote about “some barefoot bum in some pesthole in Central Asia” with an image of a girl walking through a desolated, rural area while clenching books inher hands. Her head scarf frames her high cheek bones and almond-shaped eyes. Although these images are unknown to the Western viewer, the connection between Randian and Soviet ideologies is definitely not a new subject. (A quick internet search gives pages of materials which link Rand’s pro-right ideas with Stalinist propaganda, including the style of Socialist Realism as its visual manifestation.)

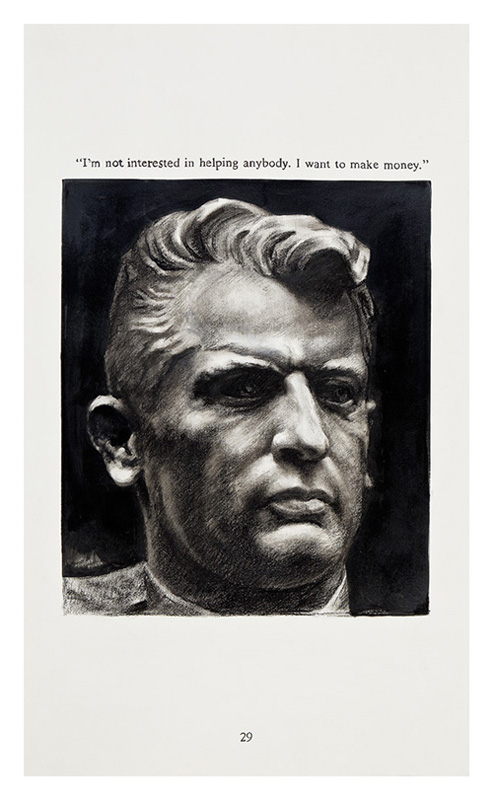

There are several works, however, that raise questions: in one sheet, a portrait of a handsome man, open-faced with styled hair, is accompanied by the phrase: “I want to make money.” In another, a bronze sculpture of a Russian officer is followed by a description of his vision: “He traced in space the sign of the dollar.” Of course, we are reminded of Rand’s unapologetic promotion of capitalism; there is little humility, irony or (self-) critique when she writes on behalf of the book’s protagonist, Galt: “I don’t care about helping anyone, all I care about is making money.” This openly stated call for money-making feels uneasy, and perhaps Fiks’ challenge to the viewer is to decide what role money truly plays in life.

There are several works, however, that raise questions: in one sheet, a portrait of a handsome man, open-faced with styled hair, is accompanied by the phrase: “I want to make money.” In another, a bronze sculpture of a Russian officer is followed by a description of his vision: “He traced in space the sign of the dollar.” Of course, we are reminded of Rand’s unapologetic promotion of capitalism; there is little humility, irony or (self-) critique when she writes on behalf of the book’s protagonist, Galt: “I don’t care about helping anyone, all I care about is making money.” This openly stated call for money-making feels uneasy, and perhaps Fiks’ challenge to the viewer is to decide what role money truly plays in life.

In relation to contemporary society in Russia, the artist once said “they think that new money will buy a new happiness.” Rand’s text may well be used to gesture towards the Russian nouveaux riches, addressing their pro money-making urges. In his past projects Fiks has addressed the desire for market and goods. His 2008 exhibition, Adopt Lenin, sought to undermine the value of objects from the Soviet era, as well as the surrounding cult of memorabilia. But his concept is muddled: Fiks almost reinforced the objects’ “fetish status” by enveloping each piece in convoluted contractual restrictions.

Similarly, in Ayn Rand in Illustrations, the question remains open as to whether Fiks sanctions these ideas in the context of a newly emergent post-Soviet consciousness; or, whether his images are meant to show the dark and oppressive underside of the kind of individualism/objectivism that Rand openly promotes. It appears as if text and image may just be decoratively placed together, which would reduce them to fashionable consumer art objects (hence the book-like paging of his works). By prioritizing the works’ aesthetic appearance, the artist might have overlooked these conceptual contradictions.

See also “Yevgeniy Fiks, Ayn Rand in Illustrations (Exhib. Review)” by Olga Kopenkina.