The Artist is Present: Marina Abramović at MoMA (Review Article)

MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ, THE ARTIST IS PRESENT, MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK, MARCH 13-MAY 31, 2010

If in the early stages of her career Marina Abramović’s work gained much of its magnetic allure from its spontaneity and ephemerality, in recent years the artist has shown a heightened interest in the problem of how performance art – whose essential medium is time – can be preserved. Recognizing the calamity, the artist recently established the Marina Abramović Institute for the Preservation of Performance Art in Hudson, N.Y., near where she has a home (the Institute is scheduled to open in 2012). The large exhibition devoted to Abramović’s forty-year career currently at the Museum of Modern Art, however, is not content to merely preserve and document, as it also aims to literally resurrect past performances.

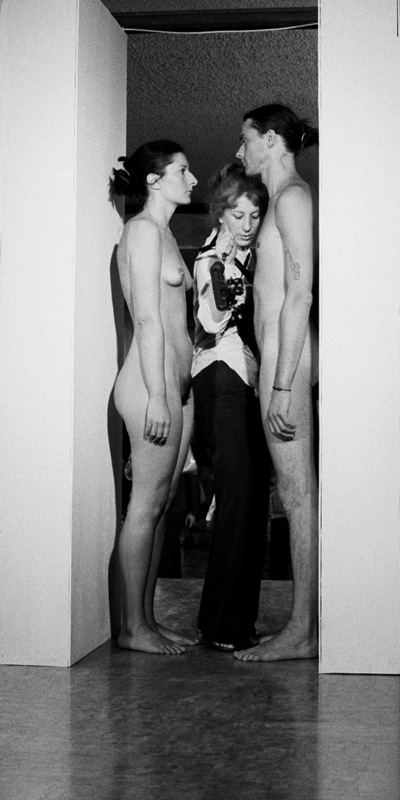

To this end the museum hired live actors – many of them dancers or choreographers – and, with Abramović’s help, trained them to re-enact several of her past performances. These come mostly (but not exclusively) from the productive period of the artist’s collaboration with her then partner Ulay [Uwe Laysiepen] during the 1970s and ‘80s. Many of them are signature pieces, highlighting their efforts to push the (often contradictory) limits of abject discomfort and heroic endurance. The pieces re-enacted with live actors include Imponderabilia (Abramović and Ulay standing naked in the main entrance to a museum, 90 mins. [stopped by the police], 1977); Relation in Time (Abramović and Ulay sitting back to back, tied together by their hair, 2 parts; 17 hours total, 1977); and Point of Contact (Abramović and Ulay standing opposite each other, pointing at each other with their index fingers raised but not touching, 1 hour, 1980).

Re-enactment has been a part of Abramović’s work for some time, going back to 2002 and 2003 (at the Whitechapel Gallery in London) when she organized two series of re-enactments of her own work (in 2005 she went on to re-perform works by artists such as Bruce Nauman, Vito Acconci, and VALIE EXPORT, among others). However, one may wonder if MoMA’s recreation of performances with actors can match the kind of intensity often generated by Abramović herself as she re-performed her own work or that of others. I would argue that they do not. Ever since the show opened, New York newspapers, including The New York Times, have been full of graphic accounts of the kind of “inappropriate behavior” visitors have shown the performers, and of the occasional erections allegedly sported by visitors and performers alike. This kind of response, which only goes to show how far we are today from the turbulence of the 1970s (it was in 1973 that Vito Acconci ejaculated, behind an artificial floor, in New York’s Sonnabend Gallery), may seem trivial and disappointing. Times have changed and the potential these performances had in the 1970s to challenge institutional boundaries – or any other boundaries, for that matter—may have evaporated in the forty years since then, or they simply do not work without Abramović herself.

The way these theatrical tableaux vivants are deployed in the gallery does not help. In the first performance of Imponderabilia, which was shut down by the police, Abramović and Ulay had faced each other at the entrance to the Galleria Comunale d’Arte Moderna in Bologna so that every visitor had to squeeze through in between the naked artists in order to reach the museum’s interior space. The decision visitors had to make before entering the gallery was not only whether to enter or not, but also which of the two artists they would be facing (Abramović or Ulay). The piece deals, in a 1970’s kind of way, with institutional (not just personal) boundaries and with the role of the artists in the museum. In the MoMA version, the performance has been moved away from the gallery entrance so that there is no longer any access issue. Whether or not we decide to walk in between the two naked performers is of no consequence as no thresholds – institutional or otherwise–are crossed. And that makes all the difference.

The way these theatrical tableaux vivants are deployed in the gallery does not help. In the first performance of Imponderabilia, which was shut down by the police, Abramović and Ulay had faced each other at the entrance to the Galleria Comunale d’Arte Moderna in Bologna so that every visitor had to squeeze through in between the naked artists in order to reach the museum’s interior space. The decision visitors had to make before entering the gallery was not only whether to enter or not, but also which of the two artists they would be facing (Abramović or Ulay). The piece deals, in a 1970’s kind of way, with institutional (not just personal) boundaries and with the role of the artists in the museum. In the MoMA version, the performance has been moved away from the gallery entrance so that there is no longer any access issue. Whether or not we decide to walk in between the two naked performers is of no consequence as no thresholds – institutional or otherwise–are crossed. And that makes all the difference.

In its more conventional parts, the show at MoMA does a good job of documenting Abramović’s career over the last four decades. Coming of age in Belgrade the artist began with projects for sound environments and installations, some of which were impossible to realize in Socialist Yugoslavia under Tito. Some of them worked with an avantgardist dissociation of the senses – what you heard was not what you saw and vice versa. For example, in the (unrealized) project The Bridge (1971) Abramović installed loudspeakers on a bridge that would emit the sound of a bridge collapsing.

Such mismatches between hearing and seeing were not only familiar to anyone who grew up in the contradiction-fraught atmosphere of “real existing” socialism, they also point to a medium with which performance art shares a reliance on the temporal, that is film. Just as a film establishes a narrative through the spatial contiguity of two unrelated frames, so The Bridge lined up two sensory experiences that, though unrelated, work to establish a sense of unity – as if the sound and the bridge we see actually did belong together.

The cinematic way in which unity is born from dissociation in The Bridge points to another crucial element in Abramović’s activities, the psychoanalytical principle of Übertragung, or transference. Transference is the (often inappropriate) redirection of thoughts or feelings from one object or person to another. The concept may help explain the often oblique yet powerful hold that her childhood in a privileged family of respected WWII heroes, along with the history of the Balkans in general, has had over the artist.

In the mid-1970’s she created a performance entitled Lips of Thomas at Krinzinger gallery in Innsbruck during which she cut a five-pointed Communist star into her belly. In the mid-1990s she re-performed this action wearing her mother’s wartime partisan cap with the same star prominently on its front, and weeping. In other works from the 1970s – her most memorable, perhaps—Abramović’s energy was directed at more exposing transference in others by getting her audiences to act out. In Rhythm 0 (1974), she famously invited the public to use a “buffet” of instruments (food, drink, comb, scissors, paint, strings, a gun, etc.) to do to her body whatever they wished. At one point, a visitor loaded the gun, put it in the artist’s hand and held it up to her temple. In the end, Abramović was visibly shaken, her naked body bruised, painted, and in pain. The scene, documented in a jarring series of photographs, not only promotes a mythical image of the artist as martyr, it also encapsulates what feminists love to hate most in Abramović.

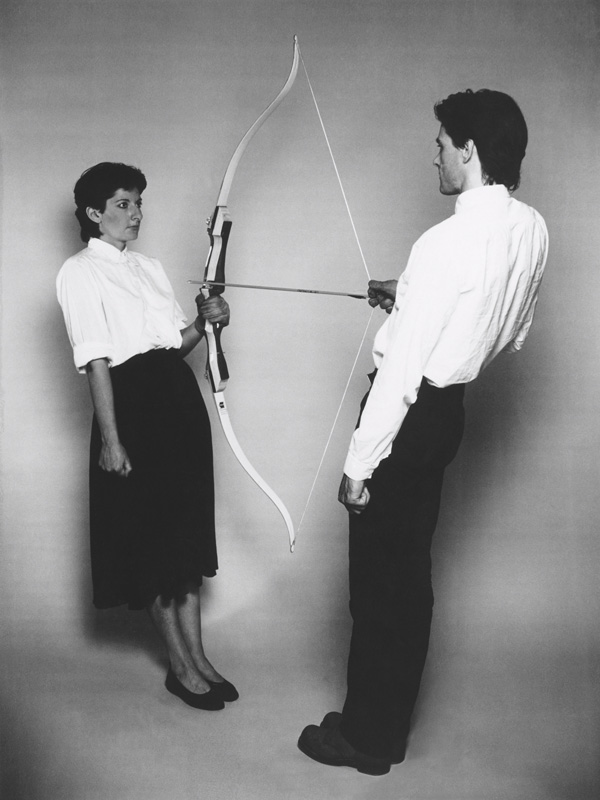

The works she created with Ulay often focus on a formalized ritual of struggle. They are agonistic also in the sense that for all their open-endedness and spontaneity they can seem oddly literary. In ancient Greece, the agon was a formal debate between the chief characters in a Greek play, with the chorus acting as judge. In Abramović’s cooperation with Ulay, struggle often has a dialogic, weirdly literary character. In Balance Proof (30 min., 1977), she and Ulay hold a double-sided mirror between their bodies. In AAA-AAA (15 min., 1978) they face each other, screaming at the top of their voices into each other’s mouths until exhaustion. In Charged Space (32 min., 1978) the two artists hold each other’s hand and spin around until they lose control and their bodies start moving around the room randomly. In Rest Energy (4 min., 1980), Abramović and Ulay are holding a taut bow with the arrow pointing at Abramović’s heart. As her re-performances of other artists’ work also testify to, the agonistic element in Abramović’s work, which itself translates into the agony we experience when we watch the artist push herself to the limits, is misunderstood if we view it solely as a form of solipsism: it is actually a form of dialogue.

The works she created with Ulay often focus on a formalized ritual of struggle. They are agonistic also in the sense that for all their open-endedness and spontaneity they can seem oddly literary. In ancient Greece, the agon was a formal debate between the chief characters in a Greek play, with the chorus acting as judge. In Abramović’s cooperation with Ulay, struggle often has a dialogic, weirdly literary character. In Balance Proof (30 min., 1977), she and Ulay hold a double-sided mirror between their bodies. In AAA-AAA (15 min., 1978) they face each other, screaming at the top of their voices into each other’s mouths until exhaustion. In Charged Space (32 min., 1978) the two artists hold each other’s hand and spin around until they lose control and their bodies start moving around the room randomly. In Rest Energy (4 min., 1980), Abramović and Ulay are holding a taut bow with the arrow pointing at Abramović’s heart. As her re-performances of other artists’ work also testify to, the agonistic element in Abramović’s work, which itself translates into the agony we experience when we watch the artist push herself to the limits, is misunderstood if we view it solely as a form of solipsism: it is actually a form of dialogue.

Abramović last work with Ulay was The Great Wall Walk (1988), during which both walked separately, for 90 days and from opposite starting points, the entire length of the Great Wall of China until they finally met in a specified place. The artist’s post-Ulay work has tended to focus on immersive, often theatrical invocations of Balkan myths. Central to this was her contribution to the 1997 Venice Biennale, Balkan Baroque, an effort to work through the historical experience of the recent Balkan wars. The artist spent four days on top of a large mountain of bloody cow bones in a smelly, sweltering basement, cleaning them one by one while she was singing Balkan folk songs and weeping. In an accompanying video installation Abramović was seen in a white hospital gown, giving a lengthy and torturously detailed explanation of how rats are killed in the Balkans.

The re-staging of this performance at MoMA is a valiant effort (a large heap ofclean bones is present in the gallery) but it has none of the visceral pathos that marked the original piece. The often Baroque flavor of Abramović’s more recent work (including persistent references to memento mori; pronounced dualism; and a lavish visuality that contrasts sharply with her more conceptual orientation in previous decades) is also present in Cleaning the Mirror #1 (1995) which has Abramović scrub a skeleton in her lap, and in Nude with a Skeleton (2002, re-enacted in this show), in which the artist lies naked with a skeleton on top of her that moves up and down with every breath she takes.

The re-staging of this performance at MoMA is a valiant effort (a large heap ofclean bones is present in the gallery) but it has none of the visceral pathos that marked the original piece. The often Baroque flavor of Abramović’s more recent work (including persistent references to memento mori; pronounced dualism; and a lavish visuality that contrasts sharply with her more conceptual orientation in previous decades) is also present in Cleaning the Mirror #1 (1995) which has Abramović scrub a skeleton in her lap, and in Nude with a Skeleton (2002, re-enacted in this show), in which the artist lies naked with a skeleton on top of her that moves up and down with every breath she takes.

In her infamous House With an Ocean View (2002) Abramović lived for twelve days in three suspended open boxes in Sean Kelly Gallery in Chelsea, allowing visitors to watch her sleep, shower, get dressed and undressed (she wore clumsy bright-colored overalls), drink, and use the toilet. Like a canary bird in a cage, she had nowhere to hide from the riveted gaze of the art world. House with an Ocean View has much in common with The Artist is Present, the live performance Abramović prepared especially for her show at MoMA. The piece has the artist sit in a long theatrical red robe at a table in the museum’s massive, brightly-lit atrium. A partial recreation of Nightsea Crossing (1981-87, with Ulay, 22 performances), Abramović, this time around, will perform for an incredible amount of time–the entire run of the exhibition. Her partners are audience members who can choose to sit across from her for an unspecified amount of time. For all its operatic pathos, The Artist is Present is impressive, creating an effective bridge to the exhibition five floors above it. Confronted with the younger Abramović in the videos and photographs, and connecting these documents with the person who is sitting five floors below, the visitor suddenly understands what makes the live performance so infinitely more memorable than the well-meaning live reenactments in the exhibition itself: it is the simple yet decisive fact that “the artist is present.” ??????????? WEB ?????? SEO kaina www.seopaslaugos.com