Special Issue: Art and the Environment in East-Central Europe Introduction

Art and the Environment in East-Central Europe is an editorial project born from interviews and other forms of interaction with artists and cultural producers concerned, in one way or another, with the idea and the material reality of what goes by the name of the “natural environment.” In the different pieces collected within this project, the term “environment” unfolds into a broad variety of concepts and artistic practices that do not, and should not, become homogenized. A survey rather than a deep investigation, Art and the Environment in East-Central Europe covers a wide range of art and ideas connected to ecology, sustainability and the nexus between environment, art, and political action, from the perspective of the following participants: Barbara Benish, Nina Czegledy, Maja and Reuben Fowkes, Oto Hudec, Tamás Kaszás, Attila Nemes, Marjetica Potr?, Rudolf Sikora, Matej Vakula, Kasia Worpus-Wro?ska, and Jana Želibská. The project, which stretches across ARTMargins print journal (#3.2. 2014) and ARTMargins Online, investigates pronounced, and so far largely unnoticed, environmental accents within nonofficial art practices in the countries of the former Eastern Bloc, including escapism, redefinitions of public space, permaculture and romantic views of the natural world.

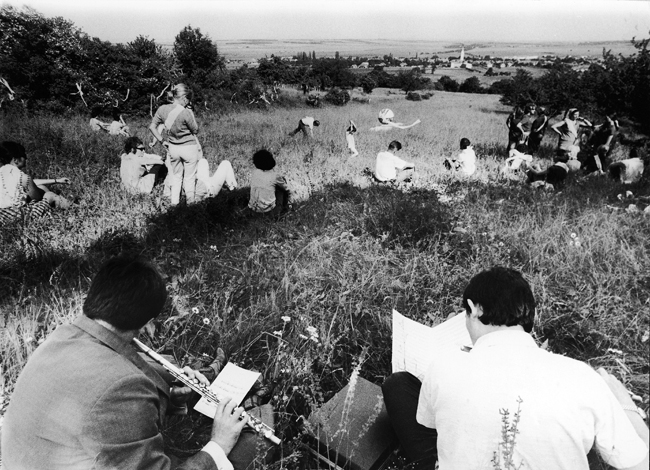

Two central temporal axes emerge: first, the period of the Cold War, when environmental pressures in parts of Eastern Europe mounted inexorably and prompted some artists to develop art practices that variously reflected on these pressures; and second, the post-1989 era with its specters of globalization and global warming posing another, even more far reaching, threat. As far as the period of the Cold War is concerned, the social and political climate during the 1960s and 1970s encouraged certain artists, and not just in Western Europe, to engage with the natural environment. From Land Art to other environmentally conscious art practices—understood in broad terms, and including nature, the urban environment, and even the artist’s studio—these artists began to travel, radically questioning assumptions about making and exhibiting art. For example, in the early 1970s, Jana Želibská positionedher studio and gallery alongside waterways and in rural fields outside of small villages in the Slovak countryside. In these spaces she made work that explored feminist and mystical themes that fell outside of the official Social Realist work that was approved by the regime.

Two central temporal axes emerge: first, the period of the Cold War, when environmental pressures in parts of Eastern Europe mounted inexorably and prompted some artists to develop art practices that variously reflected on these pressures; and second, the post-1989 era with its specters of globalization and global warming posing another, even more far reaching, threat. As far as the period of the Cold War is concerned, the social and political climate during the 1960s and 1970s encouraged certain artists, and not just in Western Europe, to engage with the natural environment. From Land Art to other environmentally conscious art practices—understood in broad terms, and including nature, the urban environment, and even the artist’s studio—these artists began to travel, radically questioning assumptions about making and exhibiting art. For example, in the early 1970s, Jana Želibská positionedher studio and gallery alongside waterways and in rural fields outside of small villages in the Slovak countryside. In these spaces she made work that explored feminist and mystical themes that fell outside of the official Social Realist work that was approved by the regime.

Another Slovak artist concerned with extending the traditional boundaries of the studio and the gallery was Rudolf Sikora. Through his project Out of the City (1970), Sikora took walks out of town into the countryside, which he documented through images and text, to escape the industrialization and pollution of the capital Bratislava. At the same time, he began to explore his relationship to earth’s larger ecosystem and even the cosmos, developing an understanding that he was one with the universe. This philosophy and way of being shaped his art, political thinking and activism, leading up to Sikora’s co-founding of Public Against Violence, a political movement that helped bring an end to communism in Czechoslovakia on November 20, 1989.

It would be a fallacy to reduce the environmental work of the artists included in this project to the vocabulary of 1970s and ’80s (Western) ecological activism, even where, in some cases, that vocabulary did inform their thinking. To an equal degree, these artists responded to other, more regionally specific discourses, including the Marxist understanding of the environment and its (often distorting) elaboration in “really existing Socialism” of the 1970s. Beyond that, it is crucial to bear in mind that what is “environmental” in art from the former Eastern Europe had other connotations as well, including an often romanticizing, escapist version of Voltaire’s famous call to cultivate one’s garden (“Il fault cultiver notre jardin”). The privatism of one’s garden understood as an autonomous ecological environment (ecology < Greek oikos = “house”) may further represent a counterpart to Eastern European artists’ fierce insistence on aesthetic autonomy, an insistence that surely had its own political dimension.

As I mentioned, the second entry point into this project are the environmental changes and challenges that occurred more recently in the wake of globalizing trade, and climate change. Like their contemporaries in other parts of the world, an increasing number of post-1989 Central and Eastern European artists are today working in Social Practice, building new systems and using permaculture, preservation and environmental education to start conversations about our collective future. In this way, they seek to engage, with varying degrees of success, communities in collaborative projects, using art as a tool to encourage environmental stewardship, and investigating the use and definition of public space at a time when that space is increasingly monitored, politicized and disappearing. Maja and Reuben Fowkes reflect upon environmental art from the Socialist era to contemporary artistic practices in their essay for ARTMargins print and in their interview included here.

In his project and essay Manuals for Public Space, Slovak artist and writer Matej Vakula touches on the history of Czechoslovak dissident artists, such as Rudolf Sikora, meeting in the countryside to produce exhibitions and plan political actions. He connects these events to contemporary artists who are turning to the land to escape from the recent economic crisis. Vakula calls attention to the rapid privatization of public space, both in cities and in nature, since the fall of the Berlin Wall and then proposes solutions through the workshops that he produces through his Manuals for Public Space project.

In his project and essay Manuals for Public Space, Slovak artist and writer Matej Vakula touches on the history of Czechoslovak dissident artists, such as Rudolf Sikora, meeting in the countryside to produce exhibitions and plan political actions. He connects these events to contemporary artists who are turning to the land to escape from the recent economic crisis. Vakula calls attention to the rapid privatization of public space, both in cities and in nature, since the fall of the Berlin Wall and then proposes solutions through the workshops that he produces through his Manuals for Public Space project.

A critique of the increasingly developed and globalized world can be seen in Oto Hudec’s project, If I had a River (2012) for which the artist built a life-sized boat that contained a vegetable garden. He had the utopian idea that in this way he and others could sail out of the current environmental mess into a brighter, more sustainable future. Installed in a gallery, Hudec’s boat, which integrated art, permaculture and ecology, was a place where visitors could tend the garden and harvest their own food. If I had a River encouraged the audience to think about the industrialized production of food and the future of the planet for, as Hudec well knows, there is no escape without political will and action.

After working many years as an advocate for affordable housing and public access to empty lots and abandoned buildings, Budapest-based Tamás Kaszás took the literal step of leaving the city and working on a small island in the middle of the Danube where he and his partner, the artist Anikó Loránt, are forging a “back to the land” way of life that includes making sustainable art. Creating artworks that transmit Hungarian folk knowledge about edible and medicinal plants, Kaszás and Loránt represent a practical approach to integrating art and nature.

In their project, Budapest Farmer’s Hack, Attila Nemes and Péter Eszes use technology to support practical solutions to the post-communist decline of small vegetable plots in the city. In an effort to create opportunities for university art and technology students to interact with the community, Nemes and Eszes are fostering sustainable relationships as well as sustainable food resources.

In their project, Budapest Farmer’s Hack, Attila Nemes and Péter Eszes use technology to support practical solutions to the post-communist decline of small vegetable plots in the city. In an effort to create opportunities for university art and technology students to interact with the community, Nemes and Eszes are fostering sustainable relationships as well as sustainable food resources.

“Challenging the idea that one has to be in the city to make a difference,” artist Barbara Benish founded ArtMill Center for Sustainable Creativity, in the late 1990s, in a place halfway between Prague and Munich, near one of the largest and oldest greenbelts in Europe. Producing exhibitions, summer camps for children and adults, publications, and environmental projects that stretch out far from the borders of the Czech Republic, Benish makes a case for using art as a tool for social and environmental change.

An interview with Marjetica Potr? reflects on the role of the artist as mediator and the idea of engaging citizens in participatory projects with a view to shaping the urban environment. From community gardens to architecture, this engagement, she argues optimistically, leads to sustainable change that continues long after the artist has left the site.

Nina Czegledy also reflects on participatory elements in the production of collaborative projects that often unfold over a period of several years. Her project Aura Aurora (2010-2013) used current technology for a dialogue between the naturally occurring electro-magnetic disturbances of the Aurora Borealis and humanity’s everyday existence. In another project, What Will You Do to Help Us Cool the Earth? (2007-2009), Czegledy reflects upon human behavior in connection with climate change.

A photo essay of landscapes by photographer and graphic designer Kasia Worpus-Wro?ska concludes Art and the Environment in East-Central Europe. Her formally constructed images of trees, fog, snow and hikers in Poland’s Beskids Mountains imply a reverence for nature and light. She shows that a natural place, even one that has been destroyed by centuries of logging, planting and regrowth, can retain qualities that may move us to think beyond our own existence.

My own work as a cultural producer in East-Central Europe began in 2006 when I was a Fulbright Scholar teaching at the Academy of Fine Arts and Design in Bratislava, Slovakia. During that time I set out to understand how people’s lives had changed since the fall of the Berlin Wall and the subsequent end of communism. The stories that people told were so compelling that I began to write them down, and over time these conversations turned into a four-country, multi-platform oral history project, Voices From the Center. I used the process from Voices From the Center, extended interviews and conversations edited into concise pieces and image essays, to shape the content for Art and the Environment in East-Central Europe. At times, the conversations collected here include my own questions and comments; elsewhere they are presented as a narrative, edited and rewritten by the artists and myself. While these divergent styles present some stylistic challenges to the overall project, it is an authentic reflection of the tone and work of each individual artist. In the end, the individual pieces are meant to stand alone, under the roof of a project that broadly explores one, expansive theme.

Travel support for Art and the Environment in East-Central Europe funded in part by Trust for Mutual Understanding.

In 2006-2007, Engelstad was a Fulbright Scholar at the Academy of Fine Arts and Design in Bratislava, Slovakia, where she developed and taught a class in art as social practice. Based on her success in the Fulbright Program she was invited by the US embassy in Bratislava to create, with her students, the first site-specific exhibition at a US embassy. An outgrowth of her Fulbright experience was Voices From the Center, a multi-form project and interactive, website, exhibitions and public programs that documented people’s reflections about life during and after communism.(See https://www.artmargins.com/index.php/6-film-a-video/656-reflections-central-european-artists-on-their-work-and-the-post-communist-condition.)

Janeil Engelstad is an affilate artist at the Social Practice Art research Center at the University of California, Santa Cruz. She has written curricula and taught learners of all ages at a variety of institutions, including community centers, K – 12 schools, and art centers. As an artist, administrator, educator, and curator Engelstad produces multiform projects that have environmental, social, and historical concerns. In 2010, she founded the nonprofit Make Art with Purpose (MAP), an organization that produces collaborative Social Practice projects around the world, often brigning artists to the table in helping to provide soultions to local and global environmental and social concerns.

Janeil Engelstad is an affilate artist at the Social Practice Art research Center at the University of California, Santa Cruz. She has written curricula and taught learners of all ages at a variety of institutions, including community centers, K – 12 schools, and art centers. As an artist, administrator, educator, and curator Engelstad produces multiform projects that have environmental, social, and historical concerns. In 2010, she founded the nonprofit Make Art with Purpose (MAP), an organization that produces collaborative Social Practice projects around the world, often brigning artists to the table in helping to provide soultions to local and global environmental and social concerns.