Anri Sala, “Now I see”, Art Institute of Chicago

Anri Sala, Now I see, 12 October 2004 – 30 January 2005, Art Institute, Chicago

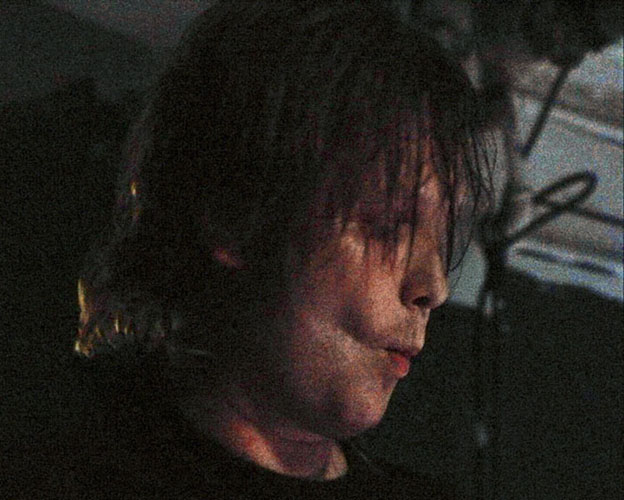

Upon entering the installation of Anri Sala’s Now I see (2004), his first 35-mm film, the viewer is enveloped in total darkness. The effect is, at first, purposefully disorienting; then a flicker of light flashes upon a 10 x 12 foot screen. A second or two later, the face of a young man emerges from the pitch-black along with the pulse of an electric guitar. What follows seems to adhere to fairly standard conventions of rock video, with its guitar antics and male posturing, until a dog-shaped balloon falls on to the stage and disrupts the scene.

Despite the film’s opening pretense, Sala is anything but a conventional filmmaker. Trained as a painter in his native Albania before studying film in France, Sala, now based in Berlin, merges an interest in color, particularly black and white, with structuralist explorations of language and sound. It is in this regard that Sala has been declared a formalist. Yet his use of overlapping narratives and ambiguous sense of time and place not only play with our visual and aural perceptions but also create, in the artist’s words, a “simulacrum of reality,” a fragmentary vision of the world that is, nonetheless, political.

Anri Sala, ‘Now I see’ (35 mm film projection, 2004).

Anri Sala, ‘Now I see’ (35 mm film projection, 2004).

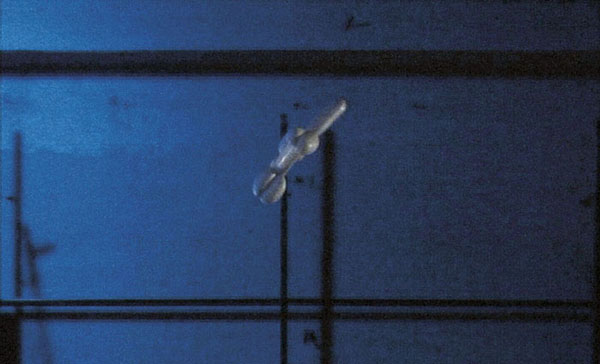

In Now I see, the political takes the form of a banal balloon that, during the film’s first sequence, steals center stage from the musicians, the Icelandic band Trabant who perform at the Klink and Bank, a concert venue in Reykjavik. The band’s nouveau-punk rhythms are silenced, and the viewer’s attention turns to the rubber dog. In the following scene, the camera shifts to the balloon that floats across the darkened stage, while the band continues to play yet recedes from our field of vision. The silence is broken by a new soundtrack, a slower electronic arrangement which, we are told in accompanying didactic information, is a remix of one of the band’s previously recorded compositions.

Anri Sala, ‘Now I see’ (35 mm film projection, 2004).

Anri Sala, ‘Now I see’ (35 mm film projection, 2004).

This rupture creates a jarring disparity between what we see and what we hear, and it is unclear, at this point, just who is performing or what is real. For the next few minutes, the dog remains suspended in midair – is it actual or a piece of digital animation cleverly choreographed by the artist? Eventually, the recorded soundtrack fades and the image of a wall bathed in colored light appears. Against this abstract backdrop, the balloon returns and drifts again to the middle of the stage. At once, the original performance resumes and we are delivered back to the temporal and psychic space of the band (did we ever leave?). The film culminates when the lead singer collapses to the floor where, in a moment of exaltation, he performs the hymn “Amazing Grace.” The viewer is captured by the slow cadence of the song’s familiar refrain, but ultimately denied redemption — the essential last phrase “I see” is never sung and the film ends.

Sala once stated that sound is “like an incomplete music,” a concept one might associate with John Cage. For Cage, however, music/sound emerged from chance happenings and the chorus of randomness. In Now I see, both image and sound are thoroughly scripted. Sala’s seamless editing blurs distinctions between live performance and planned phenomenon, although, in the end, we are never certain if either realm actually exists. This complex slight-of-hand makes clear our own willful manipulation, as well as our relationship to the order of the real.

Anri Sala, ‘Now I see’ (35 mm film projection, 2004).

Ambiguity is a hallmark of all of Sala’s films. A state of suspended belief or rather disbelief signifies freedom, a break from ideology (whether religious or political), which to paraphrase Louis Althusser is an essentially imaginary state of being. The religious is represented in Now I see by the hymn, of course, and the political in such details as the band’s name – “Trabant” is also the name of the popular East German car manufactured during the Cold War – which here becomes an economic symbol for the socialist state. The dog balloon functions as a human substitute and, more importantly, as iconoclast, within both the film’s social sites and its structural apparatus.

This new nine-minute film, commissioned specifically by the Art Institute, shares many affinities with Sala’s other works, a rather prestigious oeuvre for such a young career. The video Mixed Behavior (2004), for example, also explores the disjuncture between image and sound. A DJ mixes tunes on an unidentified rooftop in Tirana while a New Year’s Eve fireworks display lights up the sky. The music and fireworks move in and out of syncopation and, at times, seem to be controlled by the DJ who, cloaked in a plastic tarp to protect himself from the rain, has the appearance of a soldier hiding in the trenches.

In Nocturnes (1999), Sala similarly used parallel editing, juxtaposing two separate narratives that of a mercenary haunted by his actions and a recluse obsessed with his collection of fish. The characters’ reflections on the nature of life and death become metaphors for the political traumas that have plagued the Balkan region, and once again the viewer is left to decipher fact from fiction.

The dark baroque palette of Now I see, intermittently interrupted by strobelike flashes of light, is found in Mixed Behavior and in Lakkat (2004), where two Senegalese boys, nearly eclipsed in darkness, are being instructed by an unseen teacher. They repeat a series of words in their native Wolof, a language slowly being subsumed by French, which describe, as revealed in subtitles, various shades of black and white. One finds sadness and humor in the continual repetition of words and the boys’ inability to perfect them, as well as an abstract poetry heightened by occasional images ofmoths flittering upon a fluorescent light.

This Saussurean exercise speaks to loss, cultural identity, and translation, issues first explored in the earlier, potent Intervista–Finding the Words (1998). A 20-year-old videotaped interview of the artist’s mother as leader of the Communist youth alliance is discovered by chance; however, the soundtrack has been erased. With the aid of a lip reader, the mother’s words are restored calling into question her political beliefs. When combined with found television-news segments about then recent political events in Albania, the piece becomes a larger meditation on revolution and individual responsibility, truth and fiction, autobiography and history.

The political intentions of Now I see are subtler than these other works and, perhaps, mark a passage to a new set of artistic concerns. For me, Sala is at his best when these issues are more overtly stated. And although the film’s abrupt ending is deliberate, Now I see feels unresolved, like a work in progress or, better, a fragment of a larger whole. These criticisms are minor, however, as the film still resonates with many of Sala’s signature traits, the most powerful being his ability to deliver us to a reality unexplored and unforeseen.