Alina Szapocznikow’s Protean Body

Alina Szapocznikow, Alina Szapocznikow, Broadway 1602, New York, November 18, 2007 – January 12, 2008

The recent resurgence of interest in women artists and feminist art, as demonstrated not least of all by the successes of “Wack!” in Los Angeles and “Global Feminisms” at the Brooklyn Museum, has encouraged critics and art historians to extend their investigations of women artists beyond the Western-oriented feminist canon of the 1970s. One of the most fascinating individuals to come to the attention of international viewers is, in fact, not a newcomer at all, at least not in her native Poland. Although Alina Szapocznikow has long been regarded in Poland as the country’s foremost female sculptor of the postwar era, she was represented at Documenta and Frieze for the first time in 2007. During a career lasting less than three decades, cut short by her death from cancer in 1973, Szapocznikow created a striking oeuvre featuring the eroticized and often fragmented female body as its primary subject. A pioneer of what was not yet termed “body art,” she also began experimenting with plastic materials before their use became mainstream.

Following her long-overdue reintroduction to contemporary audiences in Kassel and London, Szapocznikow recently received her first North American gallery retrospective at New York’s Broadway 1602. Curated by Anke Kempkes, the exhibition introduced American viewers to Szapocznikow’s work through a limited yet representative group of works that attests to the artist’s skill in a variety of media. Kempkes, former curator at the Kunsthalle Basel, first exhibited Szapocznikow’s work in the 2004 group exhibition “Flesh at War with Engima.” Included in the New York show were several small but significant sculptures, a wide variety of drawings, and a series of conceptual Photosculptures exhibited at Documenta 12. Due in part to the gallery’s intimate space, the exhibition focused largely on drawings and studies, such as preparatory sketches for the 1967 sculpture Journey. Situating these works not only as precursors to finished sculptural products but also as conceptually and aesthetically significant pieces in their own right, Kempkes provided insight to the creative processes of a highly imaginative, idiosyncratic mind.

Post-surrealist and proto-feminist, Szapocznikow’s work defies strict categorization yet prefigures the representational strategies of several significant women artists, most notably Louise Bourgeois and Magdalena Abakanowicz. Her representations of the female body are complex and often troubling, as might be expected of an individual who reached maturity in a Europe wrought with violence. Born in 1926 to Jewish doctors in Kalisz, the artist survived internment in Auschwitz and Theresienstadt before pursuing an education in Prague and Paris. The legacy of these horrors can be witnessed in Szapocznikow’s unstable organic and female forms of the late 1950s, a period represented in the show primarily through graphic work.

In terms of its sculptural content, Kempkes’s exhibition focused mainly on Szapocznikow’s works of the late 1960s and early 1970s, when the artist infused her explorations of the female body with an erotic, pop-inspired humor. Included in the exhibition were Szapocznikow’s Illuminated Lips—desk lamp-like furnishings featuring disembodied pairs of lips that glow cherry-red when plugged in—and the Belly-Cushions, polyurethane foam pillows in the shape of a woman’s Rubinesque stomach. Cast from the artist’s own body and those of her friends, these works were conceived as playful domestic decorations and demonstrate Szapocznikow’s talent for seamlessly merging form and material(Piotr Stanislawski, Personal interview, 6 May 2006.). In their turn away from gestural abstraction and toward concrete bodily imagery, the lips and bellies loosely parallel the work of artists associated with Nouveau Réalisme, especially Yves Klein and Niki de Saint-Phalle. Accordingly, Pierre Restany noted Szapocznikow’s work for its “indefinable quality of detachment and strange serenity in humor” and became the foremost advocate of her work in France.(Pierre Restany, untitled essay in Alina Szapocznikow, Alina Szapocznikow (Paris, Galerie Florence Houston-Brown: 1967), n.p.)

Before moving permanently to Paris in 1963, Szapocznikow gained recognition in Poland for her monumental commemorative sculptures, especially the 1953 Monument to Russian-Polish Friendship. Forced to adhere to Socialist Realist decrees, Szapocznikow had little choice but to glorify the Communist party if she wished to gain recognition in her early career, and the human figures of her “official” commissions are typically stiff and heroic. Interestingly, though, the sketches from this period included in the New York exhibition present a refreshingly “unofficial” approach to Soviet-sanctioned subjects: her Study of a Group of Men of the early 1950s depicts several workers slacking on the job, while two Sketches of a Design for a Monument are entirely abstract. After Stalin’s death initiated the decline of Socialist Realism and a return of creative freedom, Szapocznikow, like many of her Polish contemporaries, reclaimed abstraction through engagement with the Parisian-based informel. Sculptures from this period bear formal similarities to the work of Jean Fautrier and Germaine Richier and are represented in the exhibition through a few preparatory sketches and a monotype from 1961.

Szapocznikow created her most innovative, experimental works in Paris, where she stayed until her death, despite frequent contact with and trips to Poland. During her final years, Szapocznikow’s investigations of the body took on a darker, more morbid character. Her Tumors series, for example, traces the development of cancerous growth within the artist’s body, and a few drawings included in the show refer to the artist’s illness and impending death. At the same time, however, Szapocznikow continued to create comical—if somewhat morbid—casts of lurid-toned female lips and breasts. In the Desserts series, these forms are piled atop glassware like scoops of ice cream. Still other works from this period evince a subtle feminist message. Two white, doll-like sculptures, entitled Fiancée Folle and Fiancée Folle Mariée, juxtapose single and married life: the latter, post-nuptial figure suffocates under gauze dressings, which resemble less a wedding gown than a makeshift shroud.

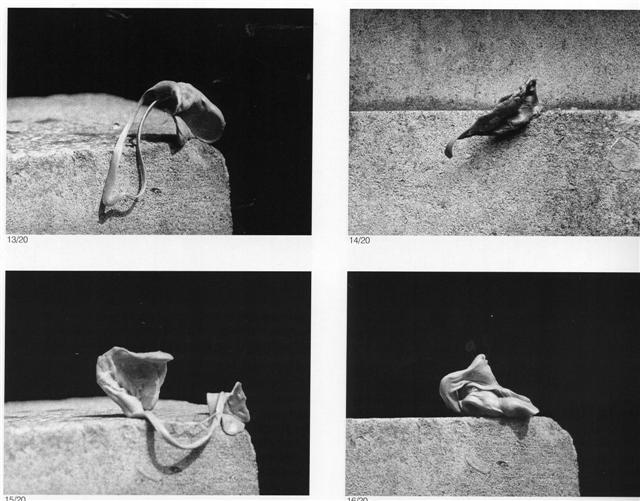

Late in her career, Szapocznikow also experimented with conceptual and process-oriented methods—partly, it seems, as a result of the limitations imposed by her illness, but also as an extension of her work with nontraditional materials. The Photosculptures series of 1971 documents Szapocznikow’s creation of ephemeral chewing gum sculptures, which take on a variety of organic forms reminiscent of her biomorphic sculptures of the 1950s. Explaining the work’s origin, she wrote, “Pulling strange-looking forms out of my mouth I suddenly realized what an extraordinary collection of abstract sculptures pass through my teeth.”(Alina Szapocznikow, “L’autre samedi,” Opus International 46, (1973): 39. Reprinted and translated in Alina Szapocznikow: Rysunki i rzezby:Zatrzymac zycie/Drawings and Sculptures: Capturing Life, ed. Josef Grabski, trans. Maja Lavergne et al, (Krakow, Warsaw, IRSA Publishing, 2004), 337.) Two other pieces highlighted in the retrospective, both entitled Grass Widower’s Ash-Tray (Cendrier de Célibataire) and likewise remaining only in photographic documentation, consist of sticks of butter speckled with cigarette butts. Choosing consumable objects—gum, butter, and cigarettes—as sculptural materials, Szapocznikow extended her investigation of corporeality to investigate substances that pass through the human body and are formally altered by it.

That Szapocznikow’s work has gone so long unnoticed in Western Europe and North America attests to the relegated status of the “other” Europe and demonstrates that efforts to reevaluate cultural achievements from behind the Iron Curtain remain incomplete. Anke Kempkes’s exhibition is undoubtedly one of the most important steps in introducing the artist’s works to a wider critical audience. Had Szapocznikow’s art been familiar to Western artists and critics during the early years of feminist debate on difference and strategies of representation, their discussions would certainly have been enriched. But today’s viewers, well-versed in the discourses surrounding body art, still have much to discover in Szapocznikow’s sculptural and graphic depictions of corporeal experience.