Alexander Ney at the National Center for Contemporary Art, Moscow (Exhib. Review)

Alexander Ney. National Center for Contemporary Art, Moscow. August 11 – 30, 2009

Alexander Ney left the Soviet Union in 1972. Now, to celebrate his 70th birthday and fifty years of artistic activity, the National Centre of Contemporary Art (NCCA) in Moscow organized a show featuring some of his pivotal works.

The show came at a stormy time for the NCCA, which is itself celebrating its 18th anniversary . At the final press conference it was revealed that the NCCA building will increase its height to seven floors and that it will become the image and likeness of the Centre Pompidou by 2015. Moreover, its first acquisitions will be works by the likes of Damian Hirst and the Chapman brothers. All this led to lengthy discussions about the judiciousness of establishing yet another costly contemporary art museum in Moscow.

The show came at a stormy time for the NCCA, which is itself celebrating its 18th anniversary . At the final press conference it was revealed that the NCCA building will increase its height to seven floors and that it will become the image and likeness of the Centre Pompidou by 2015. Moreover, its first acquisitions will be works by the likes of Damian Hirst and the Chapman brothers. All this led to lengthy discussions about the judiciousness of establishing yet another costly contemporary art museum in Moscow.

Unperturbed by these disputes the NCCA continues to present exhibitions as part of the “International Festival of Contemporary Art Collections.” Curated by Alina Fedorovich, the festival is an annual series of exhibitions that showcase artists’ private collections. In August there was a compelling show of Vadim Zakharov’s collection and archive. On the floor above, Alexander Ney’s exposition occupied the NCCA’s second exhibition space.

The Ney exhibition, which was more like a retrospective (Ney’s first), was slightly beyond the scope of the festival format. It included mostly works that Ney had at some point given to fellow artists. The curators had arranged these pieces together with those from the collection of his son Joel Ney, as well as others that were purchased with NCCA funds. Despite the August lull, the show’s opening night was attended by a large number of art-world insiders.

The Ney exhibition, which was more like a retrospective (Ney’s first), was slightly beyond the scope of the festival format. It included mostly works that Ney had at some point given to fellow artists. The curators had arranged these pieces together with those from the collection of his son Joel Ney, as well as others that were purchased with NCCA funds. Despite the August lull, the show’s opening night was attended by a large number of art-world insiders.

The fact that Ney focuses on the “internationality” of both his work and of himself as a person deprives the artist of any single cultural background. Indeed, cosmopolitanism is one of the foundations of his art and a good starting point for the analysis of his creativity. Ney – whose Russian, American and Jewish backgrounds all play important roles in his work – was in equal measure influenced by modernism (there was an important exhibition of post-Impressionist masterworks in 1956 at the Hermitage in what was then Leningrad); by ancient civilizations that he studied in the State Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography; and by the casts in the Ancient Sculpture Hall at the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow.

The fact that Ney focuses on the “internationality” of both his work and of himself as a person deprives the artist of any single cultural background. Indeed, cosmopolitanism is one of the foundations of his art and a good starting point for the analysis of his creativity. Ney – whose Russian, American and Jewish backgrounds all play important roles in his work – was in equal measure influenced by modernism (there was an important exhibition of post-Impressionist masterworks in 1956 at the Hermitage in what was then Leningrad); by ancient civilizations that he studied in the State Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography; and by the casts in the Ancient Sculpture Hall at the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow.

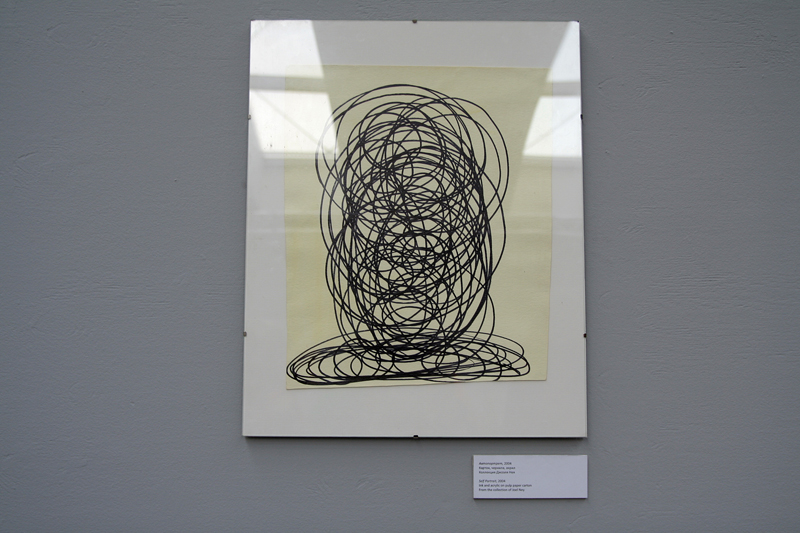

The NCCA show featured about fifty exhibits ranging from the 1969 “perforated” sculpture Portrait of the Artist to the recent abstract painting Found a Path (2009). The show started with a remarkable graphic portrait (2004) of the artist’s head, depicted in weaving black lines. Ney is a true master of line and form.

The NCCA show featured about fifty exhibits ranging from the 1969 “perforated” sculpture Portrait of the Artist to the recent abstract painting Found a Path (2009). The show started with a remarkable graphic portrait (2004) of the artist’s head, depicted in weaving black lines. Ney is a true master of line and form.

His light and transparent graphics greatly corresponded with other works in the show, especially with a line of paintings characterized by what I would call a “system of axes”: Sunrise (1972-1978); Sunset (1972-1978); Day of Spring Rain (1983), and others. In these pieces, the artist envelops the world in a series of geometrical coordinates that are usually drawn in two or three colors.

His light and transparent graphics greatly corresponded with other works in the show, especially with a line of paintings characterized by what I would call a “system of axes”: Sunrise (1972-1978); Sunset (1972-1978); Day of Spring Rain (1983), and others. In these pieces, the artist envelops the world in a series of geometrical coordinates that are usually drawn in two or three colors.

The last pictures shown at NCCA were mainly paintings and works on paper. Of these works, Lighted Road (1980) and Dream of People (1978) respectively show a laced vibration of light that fills a yellow, geometrically molded road or a dreamy scene of people in a field. Ney’s particular way of dealing with the visual world is to deprive it of distinctiveness: people simply blend in and out of his geometric landscapes.

The last pictures shown at NCCA were mainly paintings and works on paper. Of these works, Lighted Road (1980) and Dream of People (1978) respectively show a laced vibration of light that fills a yellow, geometrically molded road or a dreamy scene of people in a field. Ney’s particular way of dealing with the visual world is to deprive it of distinctiveness: people simply blend in and out of his geometric landscapes.

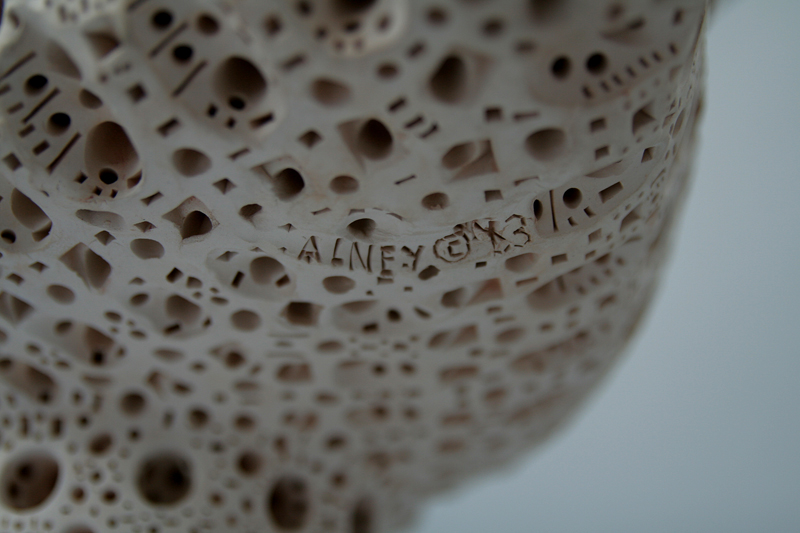

In Ney’s sculptures one feels a pervasive sense of universal order, a sense that shields the artist from the art world’s ever-changing fads. What makes these works recognizable is their “infinite” structure: his terracotta heads and figures are created from a series of depressions, holes and spots that combine to form a single image. Such a synthetic approach is perhaps at its most lucid in sculptures such as Street Musician (1978), Infinity Seeker (1983), or Majestic (1989). These works seem to refer their viewer to pre-historic, archaic times. Ney’s affection for traditional cultures is also reflected in his use of materials such as clay, sand, stone, or wood.

In Ney’s sculptures one feels a pervasive sense of universal order, a sense that shields the artist from the art world’s ever-changing fads. What makes these works recognizable is their “infinite” structure: his terracotta heads and figures are created from a series of depressions, holes and spots that combine to form a single image. Such a synthetic approach is perhaps at its most lucid in sculptures such as Street Musician (1978), Infinity Seeker (1983), or Majestic (1989). These works seem to refer their viewer to pre-historic, archaic times. Ney’s affection for traditional cultures is also reflected in his use of materials such as clay, sand, stone, or wood.

Many of Ney’s sculptures look slightly naive in the contemporary context, but that only heightens their effect. In a paradoxical way, Ney is not a contemporary artist; he operates within his own highly personal and timeless mythology, far removed from the topics of the day. Here the artist is an explorer: Ney sails through the images and sensibilities of ancient cultures, testing them under the conditions of twentieth century art.

Many of Ney’s sculptures look slightly naive in the contemporary context, but that only heightens their effect. In a paradoxical way, Ney is not a contemporary artist; he operates within his own highly personal and timeless mythology, far removed from the topics of the day. Here the artist is an explorer: Ney sails through the images and sensibilities of ancient cultures, testing them under the conditions of twentieth century art.

Another distinctive aspect of Ney’s work are his sculptures of sand and rocks, eloquent elaborations of his understanding of the human being. The most impressive examples are Man With White Dog (2000) and Living Book (1969).

There is also the infinitely supple Neighbour (2006), an impressive study of a prehistoric body’s flexibility; or Guardian of Books (1995), a head consisting of small rocks where Ney comes close to the likes of Henry Moore or Anthony Gormley. In one corner of the NCCA exhibition hall there was a series of photographs of Alexander Ney spanning different periods, from his Leningrad childhood to present-day New York. These images were the only traces of the artist at the opening night (Ney had to remain in New York due to another up-coming exhibition). Regardless, the NCCA retrospective was a first welcome step towards Ney’s comeback to the Russian art scene.

There is also the infinitely supple Neighbour (2006), an impressive study of a prehistoric body’s flexibility; or Guardian of Books (1995), a head consisting of small rocks where Ney comes close to the likes of Henry Moore or Anthony Gormley. In one corner of the NCCA exhibition hall there was a series of photographs of Alexander Ney spanning different periods, from his Leningrad childhood to present-day New York. These images were the only traces of the artist at the opening night (Ney had to remain in New York due to another up-coming exhibition). Regardless, the NCCA retrospective was a first welcome step towards Ney’s comeback to the Russian art scene.