After Stalin’s Death: Modernism in Central Europe in the late 1950s

On the evening of March 5, 1953, Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin-a man whose impact on world history cannot be overestimated-died at the Kremlin in Moscow. His influence may be measured not only by the sheer number of murdered citizens of almost every country, but also by the developments in the artistic culture of an immense area, including, in particular, the eastern parts of Europe.

Stalin’s death was the beginning of a long decline of the system in which art had played a significant role in a ruthless strategy of subjugating-above all, but not only-the nations of Eastern Europe.

A position central to communist cultural policy was that art must not be disregarded as a powerful instrument of propaganda, and its political potential must be duly exploited;(A. Lunacharsky, “Sztuka i rewolucja,” in Pisma wybrane [Selected Works], vol. I (Warszawa, 1963), 287.) this was a principle valid for some governments of the Eastern bloc until its very end in 1989.

The decline of the Soviet world was long and slow, but some distinct traces of that process, visible already in what Ilya Erenburg called the “thaw,” appeared almost immediately after Stalin’s death. The upheaval in the Kremlin and the disappearance, one by one, of the dictator’s comrades, such as Lavrenti Beria, resulted in the famous “secret speech” on Stalin’s crimes, delivered in early 1955 by his successor, Nikita Khrushchev.

Different responses which Khrushchev’s speech received in the rival communist factions of Central Europe, dominated by the USSR, determined differences among specific political strategies and cultural policies of the states of the so-called “people’s democracy.”

In Poland, the copies of Khrushchev’s “secret” address were practically available to the general public, which meant the coming end of the Stalinist regime; however, to give a contrary example, in Romania the speech was known only to the inner circle of the most reliable communists. By analogy, in Poland the “thaw” in culture had begun already in 1955, while in Romania it commenced ten years later, when Nicolae Ceaucescu came to power.

No doubt, news of the death of Stalin inspired hope all over Central Europe for some kind of “thaw,” quite often expressed only covertly.

Such hope in disguise was perhaps a sign of the times and a measure of the Stalinist captivation of Central European culture-the bleakness of the prospects soon turned out more than justified. Let us now compare two paintings-quite different, coming from two different countries and completed in two different years, yet expressing the same disguised hope for the future.

Three Literary Editors by Tibor Csernus in 1955 [Petofi Museum of Literature, Budapest] represents an interior of a cafe with three seated men. They are sitting at a table covered with a cloth, and on the table there are some glasses, a bottle, and a newspaper.

They all wear, as became the literati (at least at that time), suits and ties. A common cafe scene, quite typical of the tradition of European painting, yet this is exactly why the picture is interesting. Not long before, showing such a painting in public had been absolutely out of question, and in a sense, Csernus performed a truly revolutionary gesture, even though it was a revolution a rebours.

He referred to the tradition of the cafe as an institution of literary life while others were still painting different interiors and scenes of men wearing quite different clothes; if a man of letters ever appeared in the iconography of the socialist realism, it was not in a cafe, which the ideologues of Marxism-Leninism associated with bourgeois idleness rather than with the commitment to socialism.

According to Anatol Lunacharsky’s dictum, socialism had no place for the writer who wasted his time in a cafe; instead such an individual should take part in the life of the proletariat and implement the postulates of its avant-garde, the communist party.

Hence, rejecting the iconography of the socialist realism, Csernus went against the grain of the communist ideology, claiming the writers and the artists right to be free of the party’s pressure and to work in cafes rather than on the great construction sites of socialism. He favored the tradition of a literary culture in which the cafe represented the myth of non-commitment and liberty; of the rebellion against purposefully organized society.

Sitting in a cafe and writing (or not writing) poems is the writer’s right, as it were, to be different from (once) the bourgeois philistine or (now) the worker. Moreover, the painting contains still another set of significant elements which are particularly important from a point of view contrary to the artistic practice of the socialist realism: namely all the objects of everyday use collected on the cafe table-the glasses, the bottle, the newspaper.

According to Katalin Keseru, whose historical account of the iconography of Hungarian painting is the background of this interpretation, they bring to mind the tradition of “small still lifes” characteristic of the art under Horthy’s dictatorship, condemned-just as all the period of the admiral’s rule-by communists.(K. Keseru, “Historical Iconography of Hungarian Avant-Garde,” Acta Historiae Artium Hung., vol. 35, 1990-92: 79.)

Hence, an apparently innocent interior, normal-looking men, and common objects of everyday use acquired deep political meaning;in the era of totalitarian oppression and socialist-realist terror they expressed hope for a change, for a “thaw” that would came after long years of biting “frost.”

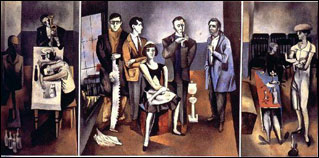

The other painting, Die Freunde-done in 1957 by the East German painter Harald Metzkes [private collection]-is equally well set in the local context of hopes for the future and possible threats. It was painted at a moment when the changes in the USSR were already well under way. On one hand in the GDR, a special French issue of the Bildende Kunst included a debate on the art of Picasso, treated by the local artists as the model of modernity, while on the other, the Central Committee of the communist party issued a declaration on the “ideological struggle for socialist culture.”

Metzkes’s painting-a portrait of a group of friends, East Berlin artists-is a triptych, referring, according to an interesting analysis by Karin Thomas, to the tradition of Beckmann.(K. Thomas, “Krise und Ich-Findung im künstlerischen Psychogramm Freundesbild und Selbstportät,” Deutschlandbilder. Kunst aus einem geteilten Land, E. Gillen (Hrsg), (Berlin: Berliner Festspiele GmbH, Museumspädagogischen Dienst, Dumont 1997), 545-547.) The scene is located in the atelier of the Academy at Paris Square, Berlin, a location made explicit by a view of the nearby Brandenburg Gate.

In the foreground, the first figure on the left is the painter himself, holding a huge saw as if he were holding a double bass, an instrument associated with jazz music and very popular among the East German bohemia yet considered decadent by the authorities. Right next to Metzkes we can see Manfred Böttcher, who later became a legendary figure of the independent art of the GDR, and the sculptor Werner Stötzner, separated from Böttcher by a sitting waitress.

Perhaps the most interesting is the fifth figure, somewhat distanced from the rest of the group-Ernst Schroeder, wearing fashionable clothes, with a cigarette in his hand, legendary not only because of his art, but also because of his original lifestyle.

This distance, writes Karin Thomas, is ostentatious, since Schroeder’s position among the other artists was quite specific.

He would often visit Paris (which explains his chic suit) and he must have been familiar with the latest trends appearing in that still unquestionable capital of modern art. In a sense, Schroeder provides a semantic key to the painting, since what is at stake here is modernity or, more precisely, the right to practice modern art, a comment emphasized by the sidepieces of the triptych referring to the wings characteristic of the Pittura Metafisica.

Moreover, the painting contains a number of references to Picasso and, particularly, to the early stages of his art (a man with the trumpet, another one sleeping on the table, as well as, on the other side, an acrobat wearing dark tights); Bernard Buffet (the figure of a woman holding a child); and the still lifes of Morandi (the bottles in the top left corner of the left sidepiece).

The picture conveys certain expectations, but also fears that the “thaw,” which has just started, may come to an end all too soon. The other motif can be derived from two coffin-like chests in the right sidepiece-a kind of requiem for the lost hopes for freedom of artistic expression.

In composing his collective portrait of the Berlin painters, Metzkes was already quite aware that, in fact, the hopes for loosening the grip of party control over the artistic culture after Stalin’s death were nothing but illusion. In the GDR the artistic “thaw” never gained momentum.

In Germany the traces of abstract painting, and particularly of the informel which at that time was the ideal icon of modernity-evidence of the freedom of expression and a sign of following current trends in art-were virtually nowhere to be found.

However, at the same time the situation in other eastern Central European countries was quite different. In Poland Tadeusz Kantor painted his best-known informel pictures (among others: Pas’akas, National Museum in Warsaw, and Amarapura, Akonkagua, Oahu, Ramanaganga, all of them in National Museum in Poznañ).(Odwilo. Sztuka ok. 1956, ed. P. Piotrowski (Poznan: Muzeum Narodowe, 1996).)

The so-called Second Exhibition of Modern Art in the Warsaw Zacheta Gallery, which was, according to Mieczyslaw Porobski,(K. Czerni, Nie tylko o sztuce. Rozmowy z profesorem Mieczyslawem Porabskim (Wroclaw: Wydawnictwo Dolnololskie, 1992), 103.) a kind of on “levy” nonobjective art, included many examples of tachisme, abstraction, and other modernist poetics. It was by no means a small, private undertaking, hidden from the sight of the authorities; quite on the contrary, party dignitaries took part in the opening ceremony that was described in detail by the national press.

The so-called Second Exhibition of Modern Art in the Warsaw Zacheta Gallery, which was, according to Mieczyslaw Porobski,(K. Czerni, Nie tylko o sztuce. Rozmowy z profesorem Mieczyslawem Porabskim (Wroclaw: Wydawnictwo Dolnololskie, 1992), 103.) a kind of on “levy” nonobjective art, included many examples of tachisme, abstraction, and other modernist poetics. It was by no means a small, private undertaking, hidden from the sight of the authorities; quite on the contrary, party dignitaries took part in the opening ceremony that was described in detail by the national press.

Some time later informel pictures appeared also in Czechoslovakia, painted by Zdenek Beran, Vladimir Boudnik, Josef Istler, Jan Kotik, and Antonin Tomalik, although they were not exhibited on official occasions attended by the party dignitaries, but rather at private shows such as, for instance, two famous, legendary “Confrontations” in Prague in 1960 and an exhibition organized under the same title in 1961 in Bratislava.(Ohniska znovuzrozeni: Ceské umeni 1956-1963, ed. M. Judlova (Praha: Galerie hlavniho mesta Prahy 1994; Sest’desiate roky v slovenskom vutvarnom umeni, ed. Z. Rusinová, Bratislava: Slovenska narodna galeria, 1995; esk informel. Prekopnici abstrakce z let 1957-1964, red. M. Nelehová, Praha: Galerie hlavniho mesta Prahy 1991; M. Nelehova, Poselstvi jineho vorazu. Pojeti “informelu” v Ceském umeni 50. a pravni poloviny 60. let, Praha: Base, ARTetFACT 1997.)

Also in Hungary, slowly recovering after the bloody Budapest uprising of 1956, not in the fifties but a little bit later, in the sixties, Krisztián Frey and Endre Tót started painting informel-like pictures definitely outside the domain of official culture. Of course, in the late fifties some traces of the informel were clearly visible in Hungary-the main inspirations were art autre or art brut, rather than the informel par excellence.

Also in Hungary, slowly recovering after the bloody Budapest uprising of 1956, not in the fifties but a little bit later, in the sixties, Krisztián Frey and Endre Tót started painting informel-like pictures definitely outside the domain of official culture. Of course, in the late fifties some traces of the informel were clearly visible in Hungary-the main inspirations were art autre or art brut, rather than the informel par excellence.

The problem of tradition is the key to understanding the function of modern art in Central Europe, both between the World Wars and in the forties, before the communist authorities started imposing a new cultural policy based on the institutionalization of the socialist realism.

If we follow the observations of Czech art historians who claim that the tradition of surrealism is a valid point of reference for the informel in general, then it turns out that the situation of the Czech artists was unique, since surrealism happened to be an essential episode in the history of the twentieth-century Czech art.

Moreover, the Czech surrealism was quite original and could not be reduced to the French model in its historical, ideological, and artistic aspects, which, of course, does not mean that it was isolated-the Czech artists produced their own idiosyncratic version of the trend.(Oesko surrealismus, 1929-1953. Skupina surrealisto v CSR: udalosti, vztahy, inspirace, eds. L. Bydzovska, K. Srp (Praha: Argo, Galeria hlavniho mesta Prahy 1996).)

“In Poland,” observed Kantor, “there was no surrealism because of the dominant Catholicism,”(Tadeusz Kantor. Malarstwo i rzezba, ed.Z. Golubiew (Krakow: Museum Narodowe, 1991), 82.) yet there, too, one could find some references to the surrealist tradition. Before World War II, surrealism was endorsed by the revolutionary Warsaw artist, Marek Wlodarski, and after the war two other artists-Marian Bogusz and Zbigniew Drubak-on their way home from the concentration camp at Mauthausen made a stop in Prague, where they also became familiar with surrealism-notably, in its Czech version.(“Od Klubu Mlodych Artystów i Naukowcow do Krzywego Kola. Rozmowa B. Askanas ze Z. Dubbakiem,” in Galeria “Krzywe Kolo”. Katalog Wystawy Retrospektywnej, ed.J.Zagrodzki (Warszawa: Muzeum Narodowe, 1990), 27.)

Besides, the “atmosphere of surrealism” was an element of the experience of a group of artists in Krakow, who during the war formed a circle of “self-education,” later to become the advocates of modernist art in their city. Mieczyslaw Porobski remembers, “we had [during the war] one number of Révolution surréaliste and one prewar issue of Nike with an article by Miss Blum.”(Czerni, Nie tylko o sztuce, 32.)

Not too much, indeed. Hence, as far as the surrealist heritage is concerned, Poland, or any other country of Central Europe, cannot be compared to Czechoslovakia; nonetheless, the tradition of the forties, regardless of its specific content, played an important role in the reception of the informel in the late fifties.

The so-called first Exhibition of Modern Art (in Krakow), which opened at the end of 1948, was to become an enormously significant point of reference for the Polish modernist “thaw.” However, on the other hand, a direct informel inspiration came from elsewhere,i.e., from Tadeusz Kantor’s trips abroad (to France). To put it ironically, Kantor brought the Polish informel in his French bags, while the Czech artists, who traveled as well, were mostly exploring their own surrealist tradition.(M. Nezlehova, Poselstvi jineho vorazu, 29 ff.)

It cannot be denied that the attitude of the authorities affected the dynamic of “thaw” and, conversely, the dynamic of “thaw” forced the authorities to take some definite stand.

One striking example illustrates a strategy adopted by the communist authorities in Central Europe with respect to modernism particularly well, namely an exhibition of the art from twelve socialist countries organized at the end of 1958 in Moscow.

Next to the works of artists from the Soviet Union, the show included exhibits from Albania, Bulgaria, China, Czechoslovakia, the German Democratic Republic, Hungary, Korea, Mongolia, Poland, Romania, and Vietnam.

The Polish exposition was unique and indeed very different from anything shown by the other delegations of the states of “people’s democracy,” which was why it attracted the attention of the public, artists, and officials. According to the spectators, the difference consisted in a distinct emphasis on modernism, sharply contrasting with the otherwise uniform style of the socialist realism. No doubt, it was also evidence of a specific attitude adopted with respect to modernity by the Polish communist authorities.

The organizers of the Polish exposition adopted an assumption that in Moscow they should show nothing but modernist art, or at least that they must not show the socialist realism as did all the other delegations.

That decision seems particularly important, no matter what was really shown in Moscow by the Poles, since when one takes a closer look at the choice of exhibits, it turns out that the dominant was not modernism par excellence, but postimpressionistic colorism and more expressive, or perhaps more allusive, forms of realism.

The selection included some abstract art interpreted as radical modernism (e.g., the works of Adam Marczynski: Kontrasty, 1957, National Museum in Krakow), but in fact abstraction was rather marginal. Still, in the present context it is significant that Marczynski’s art turned out the most appealing to the Moscow audience. “

The number of spectators in the Polish section was so high that on the second day of the exhibition our Soviet assistant asked us for permission to put up protective ropes in front of some exhibits, for example the paintings of Adam Marczynski,” remembers a participant of the show.(“Wystawa polska w Moskwie. Rozmowa z inz. arch. Andrzejem Pawlowskim, projektanten ekspozycji dzialu polskiego na wystawie sztuki krajów socjalistycznych w Moskwie,” Zycie Literackie, no. 5 (1959) (annex Plastyka, no. 30).) Nevertheless, particularly against the uniform background of the socialist realism, all that display of expressionist, postimpressionist, and abstract poetics was interpreted by the Moscow and international audience in terms of modernism.

The Moscow exhibition indicated quite clearly that the Polish authorities did not want to give up their small “portion of independence” in international relations (including culture), gained by Wladyslaw Gomulka after the breakthrough of October 1956, won in hard negotiations with Khrushchev.

The ambitions of Gomulka himself can perhaps be best illustrated with an anecdote related by Stefan Kisielewski: “Once a delegationof the Romanian Central Committee visited Poland and someone got an idea to show them an exhibition of painting at the National Museum [in Warsaw]. It turned out to be an exhibition of contemporary Polish painting, including mostly abstraction.

On seeing it, they got mad, left, and went to see Starewicz, who was then in charge of culture, to ask him what it meant, such formalism in a socialist country, such Western influences?

Then Starewicz went to Gomulka whose reaction was the following: abstract painting is not my bag, and I will talk about it with director Lorentz [of the National Museum in Warsaw], but the Romanian comrades have no right to decide about our exhibitions anyway.”(“Pomowmy o znajomych . . . Rozmowa Marka latyskiego ze Stefanem Kisielewskim,” Kontakt, no.7-8(1988),100 f.)

Obviously, the informel painting, generally, the art and culture in the Eastern bloc was carefully observed from the other side of the Iron Curtain, both by artists and intellectuals, and by politicians.

Polish painter Jan Lebenstein in 1959 won the Grand Prix de la Ville de Paris at the first Paris Biennale, which marked the climax of the international interest in the Polish modernist art of the late fifties. That interest could be seen all over Europe, and it did not stem from artistic categories only. Interpeting culture as an instrument of Cold War politics, Eva Cockroft wrote:

“Especially important was the attempt to influence intellectuals and artists behind the ‘iron curtain.’ During the post-Stalin era in 1956, when the Polish government under Gomulka became more liberal, Tadeusz Kantor, an artist from Krakow, impressed by work of Pollock and other abstractionists which he had seen during an earlier trip to Paris, began to lead the movement within the internal artistic evolution of Polish art, this kind of development was seen as a triumph for ‘our side.’

In 1961, Kantor and other nonobjective Polish painters were given an exhibition at MOMA. Examples like this one reflect the success of the political aims of the international programs of MOMA.”(E. Cockroft, “Abstract Expressionism. Weapon of the Cold War,” in Pollock and After. The Critical Debate, ed. F. Frascina (New York: Harper & Row Publishers, Icon Editions, 1985),131 f.)

Regardless of a specific answer to the controversial question whether Kantor’s painting was more a success of the Cold War strategy of the U.S. State Department than an effect of local historico-artistic processes and fascination with the French artistic scene-which at least at that time was still characteristic of all the Central European countries-the political background of the Western interest in the Eastern European “thaw” is self-evident.

The Grand Prix that Lebenstein received in Paris can be also, at least in part, explicable in such terms. Moreover, the decision to organize in 1960 in Warsaw the annual congress of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA), an institution which Poland had joined shortly before, was, in a sense, a political manifestation, too.

What is significant, however, is the character of the art inspired by the informel and its evolution. Following this process, one can realize-to quote another of Porobski’s remarks on Polish art of the fifties-that it favored the “experience of matter […] over gesture,”(Czerni, Nie tylko o sztuce, 105.) foregrounding the aesthetic values typical of the art of the matter, rather than the philosophical ones related to the classic, particularly French, painting of gesture, not to mention political overtones characteristic of the COBRA group.

That aestheticization of the informel by the “materialization” of canvas turned out quite symptomatic and historically significant.

It should be noted that the Slovak and Czech art historians have reached similar conclusions as regards modern art in their countries at that time.(M. Nezlehova, “Odvracena tval modernismu”, in: Ohniska znovuzrozeni, 174 ff. (Nezlehova quotes F. Zmejkal who in this context wrote about a “specifically Czech version of the European informel,” 192); cf. also: M. Nezlehova, Poselstvi jineho vorazu…, 242 ff. K. Bajcurova, “Pramene slobody. Strkturalna, lyrycka a gesticka abstrakcia”, in: Zest’desiate roky v slovenskom votvarnom umeni, 107 ff.) They have also stressed the aestheticization of the informel-the importance of composition, the pursuit of formal perfection and harmony of color, the approach to the painting as a finished whole, etc.

What appears particularly interesting, most likely as an effect of the Central European tradition, even the so-called structural, “materialist” painting, involving thick impasto and added pieces of non-painterly matter, has been interpreted in spiritual terms, rather than in terms of matter and the body.

That emphasis on the spiritual, underlying also the most radical experiments of art of the matter, was definitely related to the defense of culture as a domain of sublimated spirit, sharply contrasting with the materialist artistic rebellion in the West, exemplified by the art of Dubuffet, the COBRA group, or a German group SPUR.

The artists of Central Europe, living under the permanent pressure of “cultural policy” whose purpose, at times stated quite explicitly, was total instrumentalization of culture, i.e. its virtual elimination, could not approve of the subversive strategies of their Western colleagues.

While for the artists in the West, culture was an element of the bourgeois system of values, in Central Europe it was primarily an instrument of resistance against the regime. Since in the countries occupied by the Soviet troops the very concept of bourgeoisie was ambiguous, an anti-bourgeois rebellion in art must have been ambiguous just as well.

Consequently, the Central European preference for the painting of the matter may have been characteristic of the region-it may have been related to a certain delay in the reception of the informel in that geographical area or, more precisely, with a fact that Central European artists became familiar with that kind of art in an aestheticized, museum stage of its evolution when matter-a formal, rather than existential aspect-started playing the major role.

On the other hand, the tendency at the aestheticization of artistic subversion might have had deeper roots in history. Artists and intellectuals from that part of Europe were interested in a “cultural”, museum-like version of informel rather than contest. Their critique went not against culture as such, but against cultural politics of the communist power here.

After all, the idea of the defense of culture must have been much more obvious to Central Europeans who experienced its systematic politicization and instrumentalization by the Stalinist regimes. Finally, as far as informel and other similar poetics are concerned, we can observe in the divided Europe of the fifties two different attitudes to the phenomena of culture.

On the one hand, in the West, in such an art as produced by the COBRA group, culture was recognized as a sort of target in their attack on the bourgeois society. Paining of gesture meant a critique made by the artists who saw culture as an instrument of a repressive bourgeois society.

On the other hand, in the countries of the Eastern bloc, particularly in post-Stalinist Central Europe, the artists were seeking high values, namely culture, expressed by a painting of gesture or of the matter, as a remedy against cultural politics made by the communist regime.

The regime instrumentalized (politicized) cultural production in terms of propaganda, which could be clearly observed in the Stalin era by the mid-fifties and in some places for much longer.

Culture, and not its critique, has been recognized here as a strategy of resistance against totalitarian oppression, since it has been perceived as an absolute system of values, autonomy, ahistorical domain.

For Central Europeans, culture, in that case the informel painting, worked as a field of identity since it has been perceived as a part of universal European system of values, even if-or perhaps because-in the West (Europe), artists tried to criticize it as a tool of bourgeoisie.