A Conversation with Yevgeniy Fiks

In a new series of interviews with contemporary artists from Russia (“Painterly Practice and the Post-Socialist Condition”), conceived and compiled by Yulia Tikhonova, ARTMargins explores art production in the post-Soviet age, with an emphasis on painting. While the way in which Russian painters engage with the (Soviet) past will be one of the threads running through the series, it will by no means be its exclusive focus. We begin our series with a discussion with New York-based Yevgeniy Fiks. In his series of portraits devoted to current members of the American Communist party, Fiks explores his personal position with regard to the meta-narrative.

Yevgeniy Fiks’ recent solo exhibitions were held at the Lenin-Museo, Tampere, Finland (2007); the State Museum of Russian Political History, St. Petersburg, Russia (2006); and the Krasnoyarsk Museum Center (formerly the Lenin Museum), Krasnoyarsk, Russia (2006). Articles on his work have been published in: Artforum, Artforum.com, Moscow Art Magazine, and ARTMargins.

Yulia Tikhonova: Yevgeniy, tell me about the genesis of your recent projects and about your associations with Communism when viewed in the present time of post-Socialist condition.

Yevgeniy Fiks: I conceived the first of these “communist” projects of mine while working on the exhibition Post-Diaspora: Voyages and Missions for the 1st Moscow Biennale in 2005. At that point I mused on the concept of an “update” of the notion of diaspora so that it would be in sync with the subjectivity of my generation of post-Soviet artists who moved to the West in the 1990s, when a major wave of post-Soviet immigration hit Western metropolises. At that time it was a concrete, historically and geographically defined group. However, in the current context of globalization and fluid movements of people, the concepts of diaspora and exile seem to have become outdated, and we now have to talk about “post-diasporas” and “self-imposed exiles.”

Yevgeniy Fiks: I conceived the first of these “communist” projects of mine while working on the exhibition Post-Diaspora: Voyages and Missions for the 1st Moscow Biennale in 2005. At that point I mused on the concept of an “update” of the notion of diaspora so that it would be in sync with the subjectivity of my generation of post-Soviet artists who moved to the West in the 1990s, when a major wave of post-Soviet immigration hit Western metropolises. At that time it was a concrete, historically and geographically defined group. However, in the current context of globalization and fluid movements of people, the concepts of diaspora and exile seem to have become outdated, and we now have to talk about “post-diasporas” and “self-imposed exiles.”

Y.T.: Does this new time of multiple “posts” open up new perspectives, and how has your “polycentric vision” — I am using Robert Stam’s term here — been extended into a new context?

Y.F.: Yes and no. Yes, because I am able to reach further in my interventionist practice. And, no, because I cannot escape from my past, when one had to deal with the consequences of the demise of the Soviet empire, globalization and loss of Russia’s “en vogue” status. However, I am trying to articulate the difference between my generation and that of the Sots-Art artists, such as Komar and Melamid, Bruskin and Kosolapov, who left Russia in the 1970s, as well as the difference between us and those artists who never left Russia. That’s why my interest in the legacy of communism in the West is a type of investigation into the origins of this meta-narrative, which had extremely dire implications for millions of people during much of the 20th century.

I started with a project titled Lenin for Your Library?, I bought 100 copies of a key text by V. I. Lenin, Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism, and sent it to major capitalist companies here in the US and internationally, as a donation to their corporate libraries. I then collected letters of acknowledgement or rejection; I had 30 of them, which I assembled in an installation. It was an intervention, though of an ethical and radically transparent nature. And yet it was very subversive. I was trying to test the place of the communist utopia in general, and of Lenin’s legacy in particular, in the so-called post-ideological society of the West. I wanted to explore the institutional attitudes to a gift, amplified by the fact that the book was almost redundant. Some responses were actually amusing as people at the other end felt confused with regard to the purpose of my donation.

Y.T.: The concept of a gift indeed encompasses a binary opposition. Regardless of the fact that it’s given gratuitously, there is nevertheless an exchange of some kind that always takes place. Your action also carries over its circulatory signification that ensures that the object returns to the point of origin, regardless of its physical form.

Y.F.: Yes, but it’s about the economy of gifts as opposed to the economy of commodities. And, in addition, in this project I modeled a capitalist economy embedded in exchange, yet without one crucial element — money. Successively, in those cases where I received no reply, I initiated a reciprocity that reminds us about the interconnectivity and inter-indebtedness between people.

Y.T.: Your installation was displayed in the Krasnoyarsk Museum Center (formerly Lenin Museum) in Krasnoyarsk, Siberia. You described the museum Center as a thriving institution where the “spirit of Lenin is very much alive.” Yet the letters displayed along the walls allude to the “white flags” of the defeat and death of Soviet utopian ideology.

Y.F.: That’s an interesting observation. These “white flags” — the replies from the companies typed on corporate stationery, carry logos of IBM, Apple, and Amazon .com, and others.

Y.T.: Could you sketch out your current project?

Y.F.: Well, after Lenin For Your Library? my second project, titled Song of Russia, featured stills from Hollywood films which were produced at the time of Stalin’s and Roosevelt’s alliance in 1943-1944 during WW II. These films employed a visual language and rhetoric that was almost identical to those of Soviet propaganda of that period. In other words, these Hollywood films were extremely pro-Soviet. They had been produced by major Hollywood studios, cast with American actors and, of course, were delivered in English. I used three of them, namely Song of Russia, Mission to Moscow, and North Star. In fact, I was very interested in this historical phenomenon, which is mostly omitted from the history of American cinema, and I would assume that this is an intentional phenomenon. The time between the Red Scare of the 1920s and 1930s and the beginning of the Cold War bears some yet undiscovered contradictions.

Y.F.: Well, after Lenin For Your Library? my second project, titled Song of Russia, featured stills from Hollywood films which were produced at the time of Stalin’s and Roosevelt’s alliance in 1943-1944 during WW II. These films employed a visual language and rhetoric that was almost identical to those of Soviet propaganda of that period. In other words, these Hollywood films were extremely pro-Soviet. They had been produced by major Hollywood studios, cast with American actors and, of course, were delivered in English. I used three of them, namely Song of Russia, Mission to Moscow, and North Star. In fact, I was very interested in this historical phenomenon, which is mostly omitted from the history of American cinema, and I would assume that this is an intentional phenomenon. The time between the Red Scare of the 1920s and 1930s and the beginning of the Cold War bears some yet undiscovered contradictions.

It’s no surprise that these films were withdrawn at once from circulation in the US when the political balance changed, as they evidence a shameful “page” in Hollywood’s history. In addition, the dubious character of the government’s involvement was supported by rumors that the movies were in fact sanctioned by F.D.R.’s administration. I painted six canvases that presented stills that looked just like those from films of the Stalinist epoch.

Y.T.: What are you working on at present?

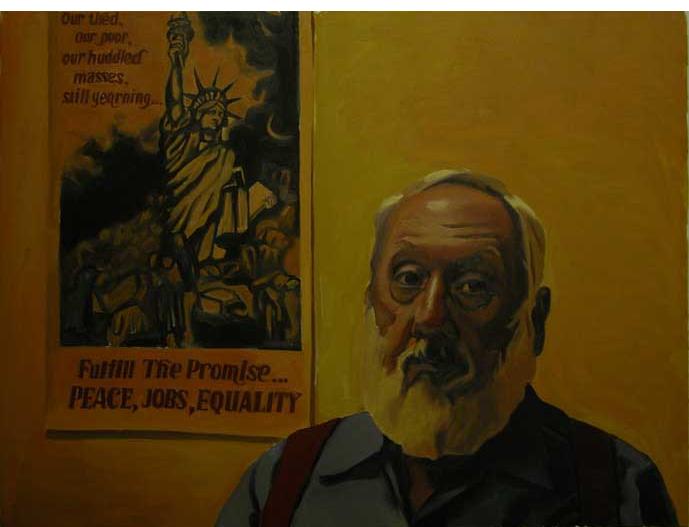

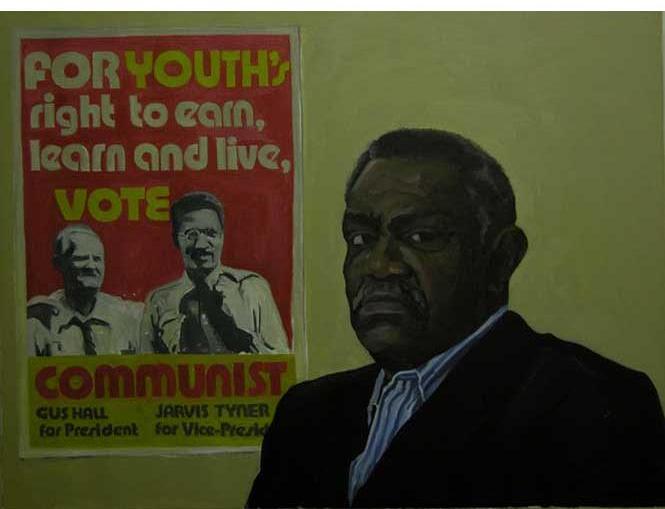

Y.F.: My current project is making portraits of present members of the Communist Party in the USA, including Sam Webb, the party’s national chairman, and Jarvis Tyner, its vice-chair, among others. I have executed eight of these portraits so far. The settings are their offices, filled with old Communist propaganda posters and modern appliances to emphasize the party’s geographic and historical (dis-) location. . In addition, the canvases are complemented by text panels that cite members’ responses to such questions as: What do you think about the Soviet Union? How do you see Mikhail Gorbachev? What’s your view of today’s Russia?

Y.T.: These conversations worked like a cross-examinations?

Y.F.: Yes, I talked with all of my sitters. Also, as part of the installation,I am envisioning including a library that comprises books about the history of American Communism, which I am collecting now. I am planning to arrange the installation in such a way that people can sit and browse books and maybe discuss it among themselves. It’s like a bit of relational aesthetics.

Y.T.: What is your relationship with painting?

Y.F.: Painting for me constitutes a reflective process, as opposed to the immediacy of a documentary photographic snapshot. These works had to be paintings because this series is really about the level of meaningfulness that a portrait of a Communist painted in 2006 in New York can attain. Of course, it’s also a reflection on official Socialist Realism and Sots ArtThe term describes the artistic style originated in 1970s that exploited themes and aesthetics of Social Realism into ridicule. The term was homonymic, designed to sound like a Soviet variant of American pop-art and bears many characteristic of its twin such as subversion, irony and anti-authoritarian mood. The style interrogated the socialist system by making a laughingstock of its foundations. It helped people overcome their fear of the authorities by laughing at them.” This style was propagated by artists Komar & Melamid and ceased its existence in 1990s. because for both of these styles oils were the most important and paradigmatic form. But instead of destroying Socialist Realism (which we normally associate with Communist propaganda) through deconstruction, irony and pastiche, as Komar & Melamid did, I’m obliterating the genre through the tactics of apolitical, somewhat naturalistic “life-painting.” No composites, no pastiche, nothing appropriated.

Y.T.: How did you find and contact members of the CPUSA?

Y.F.: I went to the Communist Party USA Headquarters on West 23rd street.I was surprised as to how my Russian name Yevgeniy opened doors there and served as a prompt introduction in many cases. The Communists themselves were mostly friendly but some of them were reluctant to talk to me. Perhaps there was a feeling of guilt. . Some were reluctant to talk as they might have found my questions overwhelming and even perhaps traumatic. Indeed, what would you expect an old American communist to say about the “good old Soviet Union”? One answer, however, stuck in my mind. A younger woman, a CPUSA member, said that the “Soviet Union is a learning tool.” I can buy that.

Y.T.: I find your personal visits to the CPUSA office and your almost year-long correspondence with them very much a form of activism. By seeking and confronting facing your “Other,” you unearth your commonality and establish your differences with these people.

Y.F.: Actually, any New Yorker faces this Communist “Other” in the city everyday in the form of architecture. For my next project, I will be photographing New York buildings and sites that had some relations to the history of the Communist Party USA. I would like to retrieve the geography of communism here in the city to unearth the hidden, parallel history of New York. It’s going to be an alternative guide to New York, the “Other,” the communist New York.

Y.T.: Clearly, the theme of the “subject versus Other” is at the core of your involvement with American Communism…

Y.F.: Again, it comes down to me being a post-Soviet artist living in New York. American communists are the internal “Other” of America. But this “Other” of America is my “Other” too. I have little patience for communist ideology in general. It’s only the historical and personal dimension of it that I’m interested in. So, the fundamental irony here is that American Communism is my “Other,” the one who is not me.

New York, 20 July 2006.