A Conversation with Ieva Epnere

This interview was conducted with Riga-based artist Ieva Epnere on the occasion of her solo exhibition Sea of Living Memories (September 17–November 5, 2016), a New Commission for Art in General in Brooklyn, NY, and part of an international collaboration curated by Zane Onckule of kim? Contemporary Art Centre, Riga, Latvia, where the show opened on December 8. Epnere’s exhibition, her first solo presentation in the United States, addresses the Soviet legacy in Latvia through the lens of those who lived and served in the former Soviet military cities along the country’s long coastline.

Ksenia Nouril: What brought you to the subject of your exhibition Sea of Living Memories?

Ieva Epnere: The first impulse came from personal experience because I am from a bilingual family: my father is Russian; my mother is Latvian. I was raised Latvian because my mother is Latvian and my maternal grandparents were Latvians. My father’s family lived in Siberia, and I never met my paternal grandparents. I went to Latvian school and primarily spoke Latvian, but with father I always spoke—and still speak—Russian. He understands Latvian, but does not speak it. Although he is now retired, he served in the Soviet army—specifically, the navy. This is what brought him to Latvia in the 1970s, when he met my mother. I was born in 1977 in Liep?ja, a town next to the Baltic Sea, which during Soviet times was a very important, strategic place. It was home to a submarine base and many military families.

KN: How do you self-identify?

IE: I think my temperament is not very Latvian. But I was raised and immersed in Latvian culture and in a Latvian environment. Of course, I identify as Latvian, but as I said, my temperament is maybe not very typically Latvian.

KN: You previously produced works that address your personal history, such as I Was Almost There (2012), a photographic series that retraces the life of your paternal great-grandmother in Russia, and The Green Land (2010), a series of photographs taken in Vai?ode, a town where there was a military aerodrome in Soviet times, where your maternal grandparents lived and where you spent many summers as a child. What made you turn now to the subject of the military and military families who lived in cities along the Latvian coast during Soviet times?

IE: I had the idea for this work when the events in Ukraine began—Euromaidan, the annexation of Crimea, the war in Donbas. A lot of things have changed recently and rapidly—not only in Latvia but also around the world. We see these kinds of signals, and then start to feel the increased activities of the Russian army, for example, in nearby Kaliningrad. It’s not very direct, but it’s present and, of course, the media sensationalizes it. The Ukrainian situation also has touched me personally because of my father, who identifies as Russian. When we start to speak about it, we always end up arguing. He has his opinions and vision of how politics should be, and I have mine. When I was invited to produce an exhibition for Art in General, all these things came together, and I felt it was the right time to talk about it.

KN: It seems like your projects, piece-by-piece, are helping you to figure out your identity.

IE: That wasn’t planned, but now, maybe in retrospect, you could say that.

KN: A lot of your work focuses on history, both personal and collective. However, in your three HD videos Sea of Living Memories for which the exhibition is named, you seem to be putting forth many histories—part truth, part fiction—as they are recounted by individuals who live through the Soviet period in the military, in military families, and in these closed costal cities.

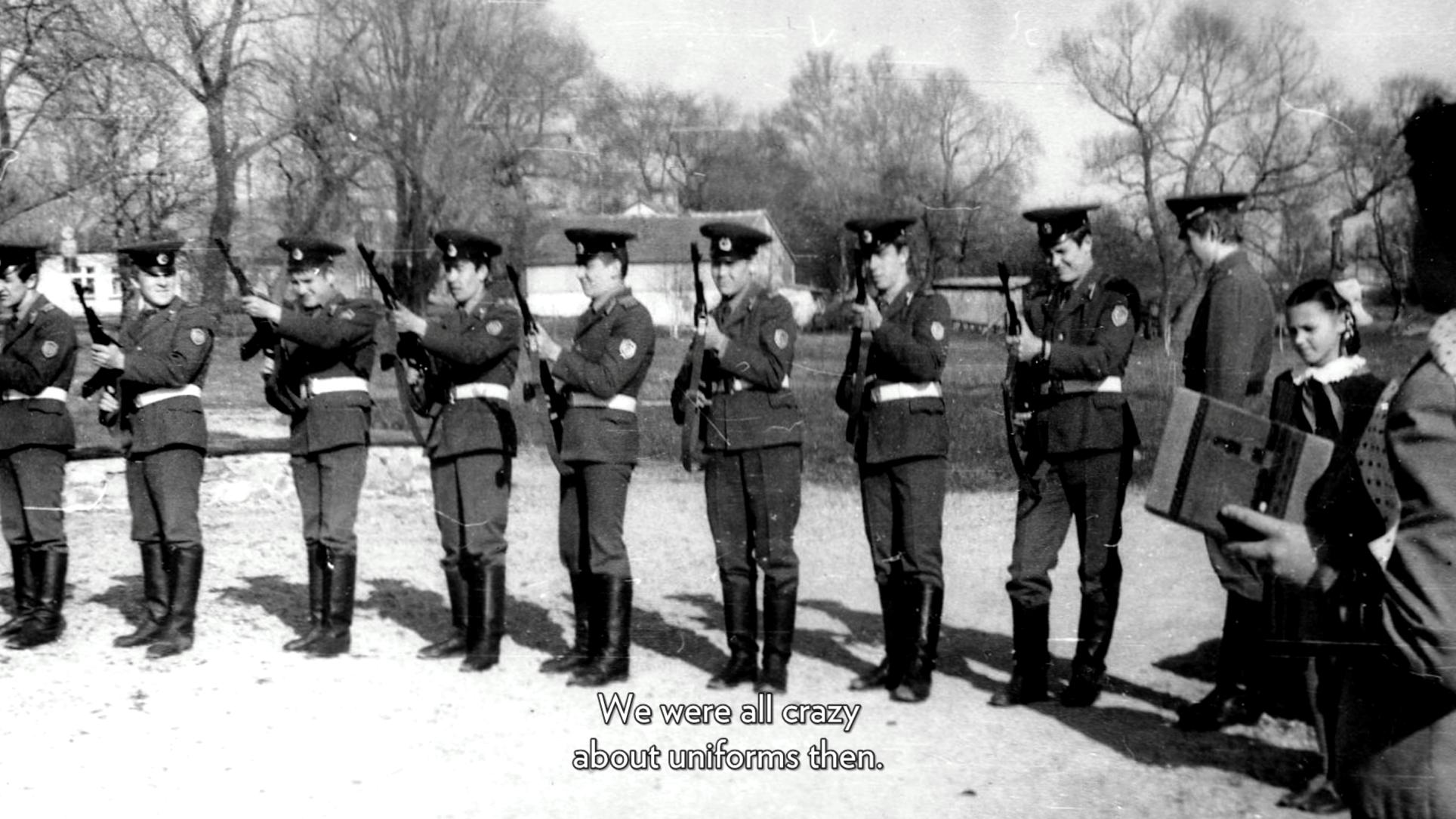

IE: Sea of Living Memories may be about the Soviet past, but it also is about our contemporary situation. We are free—Latvia gained independence with the fall of the Soviet Union 25 years ago—but our freedom is constantly in question. Are we really free? Those who worked or lived in those closed costal cities claim it wasn’t that bad. They came to terms with not being able to freely roam their hometowns or access the beaches to enter the sea. Others, of a certain older generation, don’t always want to talk about what happened. I am interested in how memory works, what it does to people, how we forget the bad memories while remembering the good ones. I want to understand the relationship between people and rules or borders. I titled the show Sea of Living Memories because the memories are still alive. The sea is like a symbol. It can hide something while revealing something else. It can be gray and cloudy or it can be clear and blue. I filmed in Liep?ja from February to late summer in 2016 because I wanted to capture different tonalities.

IE: Sea of Living Memories may be about the Soviet past, but it also is about our contemporary situation. We are free—Latvia gained independence with the fall of the Soviet Union 25 years ago—but our freedom is constantly in question. Are we really free? Those who worked or lived in those closed costal cities claim it wasn’t that bad. They came to terms with not being able to freely roam their hometowns or access the beaches to enter the sea. Others, of a certain older generation, don’t always want to talk about what happened. I am interested in how memory works, what it does to people, how we forget the bad memories while remembering the good ones. I want to understand the relationship between people and rules or borders. I titled the show Sea of Living Memories because the memories are still alive. The sea is like a symbol. It can hide something while revealing something else. It can be gray and cloudy or it can be clear and blue. I filmed in Liep?ja from February to late summer in 2016 because I wanted to capture different tonalities.

KN: Potom (Later), a large-scale twenty-minute projection, is the central work in the show. Its title is translated from the Russian. What is the story of this film and what form does it take?

KN: Potom (Later), a large-scale twenty-minute projection, is the central work in the show. Its title is translated from the Russian. What is the story of this film and what form does it take?

IE: It’s a docufiction based on historical episodes I had come to know. In preparation for the film, I had conversations with people who were in the Soviet army, and I developed the main character, an ex-military man who inhabits this dilapidated house on the coast.

KN: Who is this man?

KN: Who is this man?

IE: He is a symbol of Latvian non-citizens, former military personnel, who are relics of the Soviet past. For me, it was important to show that such people are still physically living in Latvia, but mentally they live in Russia. Most of them watch the news on Russian TV channels and read Russian-language newspapers. Of course, this is more prevalent in the older generations, but they have children who, in turn, have given them grandchildren. Entire families are raised in this way. I wanted to show the main character of Potom (Later) as a retired military officer who is a bit lost, drifting between the present and the past. There are three texts interspersed throughout the film. One tells the history of the Soviet navy in Latvia. The Soviet navy remained in Latvian until 1994; today there are still 14,000 ex-military and ex-KGB persons, a lot of them are non-citizens, living in Latvia. Another text addresses the establishment of the Latvian National Armed Forces in 1991. I wanted to show this man walking toward the sea at sunset. It looks as if he is trying to escape something, but there is only the sunset. What is he afraid of? For me, it was important to show that there is still this paranoia in the minds of ex-military persons. As they say, old habits die hard. I also wanted to point indirectly to the danger that is still present, that we are not as protected as we think.

KN: Where was Potom (Later) filmed?

IE: It was filmed in Liep?ja. The interior shots were filmed in a very special building. To use this location, I had to obtain special permission, write letters describing my project and wait a few weeks for an official response. The building, which is owned by the Latvian National Armed Forces, was built in 1907. It originally served as a meetinghouse for the Russian Imperial fleet. Later, from 1927 to 1939, during Latvia’s first period of independence, it was a tuberculosis hospital. Then, during Soviet times, it was a navy hospital.

KN: Was the character you created for this film played by an actor?

KN: Was the character you created for this film played by an actor?

IE: Yes, he is a well-known professional actor, ?irts Kr?mi?š, who performs with the New Riga Theater, which is popular not only in Latvia but also throughout Europe. Although he was not a real officer, it was important that he took on the military mentality. For example, in one scene, he does pushups. I asked him to do this so many times and only in the last show did we get it right—his muscles were finally shaking with fatigue.

KN: Are the other officers in the film actors, too, or are they real servicemen?

IE: They are officers and sailors of the Latvian navy.

KN: Tell me more about the work Sea of Living Memories (still) (2016), a wool tapestry that you produced for this exhibition?

IE: My background is in textiles. I began moving away from textiles soon after graduating from the Latvian Art Academy in the early 2000s; however, you can still see my passion for them in some of my more recent works. Sea of Living Memories (still) depicts the remains of the former fortress on the coast that is seen in the film Potom (Later). For me in was important to make this work with my own hands. In the gallery, it also acts as a symbol. In Russian and other cultures, it is common to hang carpets on walls. It serves a dual purpose—to show that you are living a good, prosperous life, and to keep the room warm. Maybe some viewers won’t know these cultural specificities, but it was my idea to play with their meanings in the context of an exhibition.

KN: What is the role of nature in Trophies (2016), a series of three archival pigment prints featuring an enlarged piece of coral, whale tooth and barnacles, also on display?

KN: What is the role of nature in Trophies (2016), a series of three archival pigment prints featuring an enlarged piece of coral, whale tooth and barnacles, also on display?

IE: In the film Sea of Living Memories, there are several moments in which coral appears – on the floor, in the corners of rooms. It is visible and invisible at the same time. The same goes for Trophies. These are the things that all military families have in their homes. I enlarged them to make them more abstract and took them out of context by photographing them within a studio set up. The blankets, which are piled up around the gallery, are also seen in the movie. I like to have this material feeling in the room that you can see and touch. These blankets are not meant to be on a pedestal. They are not to be adored. I like to have things that are there and not there at the same time. I also like the smell of the blankets. They symbolize this roughness of Soviet times – everything was basic, rough.

KN: I was struck by the painterly qualities of the meditative, panoramic landscapes in Potom (Later). The sea acts like a motif that breaks up the film into different parts. It’s interesting to think about you growing up in this place, and about your relationship not only with the army but also with nature.

IE: Our first apartment looked out directly onto the sea. As a little child, I would sleep out on the balcony at noon. The sea was always very important to me, and it is still. I think the sea is a symbol for many secrets. And it was by accident that, over a year ago, my family and I visited P?vilosta, a city featured in one of the three short documentary films. Here, we stayed in a hotel and met Solvita, a woman who was about 10 years older than me. She was our waitress, and we started talking about our pasts. We never kept in touch. A year later, when I started working on this film, I met another woman who worked in the local museum in P?vilosta, and I asked her if she knew Solvita. She reconnected us, which is how Solvita became the subject of one of my short films. This is my methodology: I have a good memory for what people tell me. Sometimes when I read, I don’t remember, but my ears have a memory of their own.

KN: Let’s talk some more about the three HD videos entitled Sea of Living Memories. You started to go back to these cities and towns and to meet these people. You have a lot of footage, yet the current films are only 10 to 12 minutes long.

IE: I was interested in people’s life stories—how they experienced life in those restricted areas, how that affected them. I filmed everyone for more than an hour, but I had to cut a lot, which was difficult. After my residency in New York, when I am back in Latvia, I will continue to work on these films.

KN: Why is documentary an important quality to preserve within the context of this larger exhibition, in which you blur the lines between reality and fantasy?

IE: While these films share personal memories and histories, they are still facts of history. While the subjects of my films are contemporaries—living through the same historical period—they have their own perspectives. I didn’t want to make a film of talking heads, but rather to show a softer even humorous side to this sometimes dark Soviet history.

KN: You’re interested in documentary that you relate to facts, and your films are documentary in that you go back to archives and to local history museums. At the same time, you’re interested in memory, which is usually never factual…

KN: You’re interested in documentary that you relate to facts, and your films are documentary in that you go back to archives and to local history museums. At the same time, you’re interested in memory, which is usually never factual…

IE: It is always an interpretation. For me, when I hear or read something, I always need to find out if it’s true. I always have to fact check. When I also talk about something, I like to be sure my facts are straight, but sometimes, there are mistakes even in facts. We’re only human.

KN: My favorite subject was Ivans, the Russian-speaking, ex-military officer who had a Latvian-speaking wife, a Latvian-speaking son, and another Russian-speaking son, who all managed to get along.

IE: Yes, Ivans is great! I was interested in finding Russian-speaking, ex-military officers, which was not very easy because they don’t want to talk and can get easily offended because most of them are now non-citizens.

KN: Can you speak more about the citizenship situation in Latvia?

IE: I think it’s very complicated that we have this kind of system. After the fall of the Soviet Union, those who wanted to become Latvian citizens had to pass an exam in Latvian history and language. Unfortunately, many military personnel chose not pursue this, nor did the older generations. Portions of the population were not willing or able to do so, for a variety of reasons. Today, they have alien passports. And they can legally live in Lativa, but they cannot vote. If they want to travel anywhere, including Russia, they must apply for a visa. It’s crazy, they are in Latvia, but, at the same time, they are not.

KN: Like this history, it is there and not there.

IE: Yes, I wanted to point out how absurd this is—non-citizens as drifters, living in limbo.

KN: Describe the last part of the show. Do you see these parts as distinct or are they one large work? Do you see this project as closed, or do you see it being developed further?

KN: Describe the last part of the show. Do you see these parts as distinct or are they one large work? Do you see this project as closed, or do you see it being developed further?

IE: While the first film can live a life of its own, the three shorter documentaries cannot. I actually want to make one long documentary. There are a lot of things I didn’t show. For example, I interviewed a woman who worked as a doctor on ships. She had begun this work when she was only 17—spending up to six months on a ship. The stories she told me were so crazy. People who go to sea are very special. Actually, they don’t know how to live on the land. At sea they are always served, there is always food prepared for them and their beds are always made. For many months at sea, men long for their wives, but when they see them during leave, they don’t know what to do.

KN: What is the role of gender in your work? In your films, you often focus on women or female characters, but in these works, the military is a very male-centric world.

IE: In the works we are discussing, my experiences and memories from my childhood play an important role. I can imagine how it was for my father to be at sea, away from his family for such a long time, and how my mother had to wait patiently for him to return. Women, whose partners work at sea, as captains or other navy officers, are always alone. These men are at sea and only return a few times per year, and then they are gone again. It’s no life! In general, the themes in my works are inspired by my own experiences. I am lucky to meet interesting, strong personalities and to be able to use their stories in my work. In regards to gender, we could have another conversation about strong Latvian women, which has a long history.

KN: You are a very strong woman—an artist and a mother.

IE: (laughs) Maybe, yes; it takes a lot of work.

KN: What do you want viewers to take away from your exhibition?

IE: Before the opening, I was afraid of the response, but at the opening, people were already asking me very sincere questions about the works. The majority of people in the United States probably don’t know much about Latvia. They know it’s a country and, maybe, where it’s located on a map, but they don’t know its history or anything about these closed areas on the Baltic Sea. Some might not know about the country’s current political situation, or that Latvia is not part of Russia.

KN: Do you see your films as didactic? Is educating the viewer your primary concern?

KN: Do you see your films as didactic? Is educating the viewer your primary concern?

IE: No, I don’t think so, but for this exhibition, I wanted to address a few sensitive subjects regarding Latvia today—the non-citizen issue, the growing activities of Russia. Almost every day, I read a lot of discouraging news. It’s really scary. We are living through really difficult times.

KN: In Latvia, what are the general population’s feelings toward these non-citizens?

IE: Latvia has always been a divided society – Latvian and Russian – and sometimes there is tension between these two rivers. We are such a small country, and if these two rivers don’t merge one day… What is most dangerous is that each has a different information space; by this, I mean the media that influences people’s opinions and creates biases.

KN: Does your film bring these two rivers closer?

IE: When I started to work on Sea of Living Memories, I felt that I should talk about this. We cannot ignore our history. I’m eager to see how these works will be received in Riga. For me, it is still too fresh. When you create, it’s so intuitive. You know what it has to be like, but you cannot say exactly why it has to be that way. I always need this time, this distance from my work, especially when I work with time-based media. After I shot the short documentary films, I didn’t touch them for months. I really wanted to get away from them. I made the tapestry, then I went back to them and edited nonstop throughout the summer of 2016.

This interview took place in New York on October 12, 2016. It was conducted in English and has been edited for length and clarity.

Ksenia Nouril is a New York-based art historian and curator. She is a Contemporary and Modern Art Perspectives (C-MAP) Fellow at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, where she researches and plans programming related to Central and Eastern European art and co-edits post (post.at.moma.org), the MoMA’s online research platform for global art. A PhD candidate at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Ksenia is writing her dissertation on contemporary Eastern European artists from Lithuania, Russia, and Poland whose practices address the legacies of communism.

Ksenia Nouril is a New York-based art historian and curator. She is a Contemporary and Modern Art Perspectives (C-MAP) Fellow at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, where she researches and plans programming related to Central and Eastern European art and co-edits post (post.at.moma.org), the MoMA’s online research platform for global art. A PhD candidate at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Ksenia is writing her dissertation on contemporary Eastern European artists from Lithuania, Russia, and Poland whose practices address the legacies of communism. Ieva Epnere (b. 1977) lives and works in Riga, Latvia. Recent solo shows include: Sea of Living Memories, Art in General, NY, (2016); Pyramiden and other stories, Zacheta Project Room, Warsaw, Poland (2015); A No-Man’s Land, An Everyman’s Land, kim? Contemporary Art Centre, Riga, and Liepaja Museum, Liepaja, Latvia (2015); Waiting Room, Contretype, Brussels (2015); and Galerie des Hospices, Canet-en-Roussillon, France (2014). Her work has also been included in several group exhibitions throughout Europe. Epnere was a resident at the International Studio & Curatorial Program in New York in fall 2016.

Ieva Epnere (b. 1977) lives and works in Riga, Latvia. Recent solo shows include: Sea of Living Memories, Art in General, NY, (2016); Pyramiden and other stories, Zacheta Project Room, Warsaw, Poland (2015); A No-Man’s Land, An Everyman’s Land, kim? Contemporary Art Centre, Riga, and Liepaja Museum, Liepaja, Latvia (2015); Waiting Room, Contretype, Brussels (2015); and Galerie des Hospices, Canet-en-Roussillon, France (2014). Her work has also been included in several group exhibitions throughout Europe. Epnere was a resident at the International Studio & Curatorial Program in New York in fall 2016.