Exchange of Ideologies: Ninotchka, 1939 — Circus, 1936

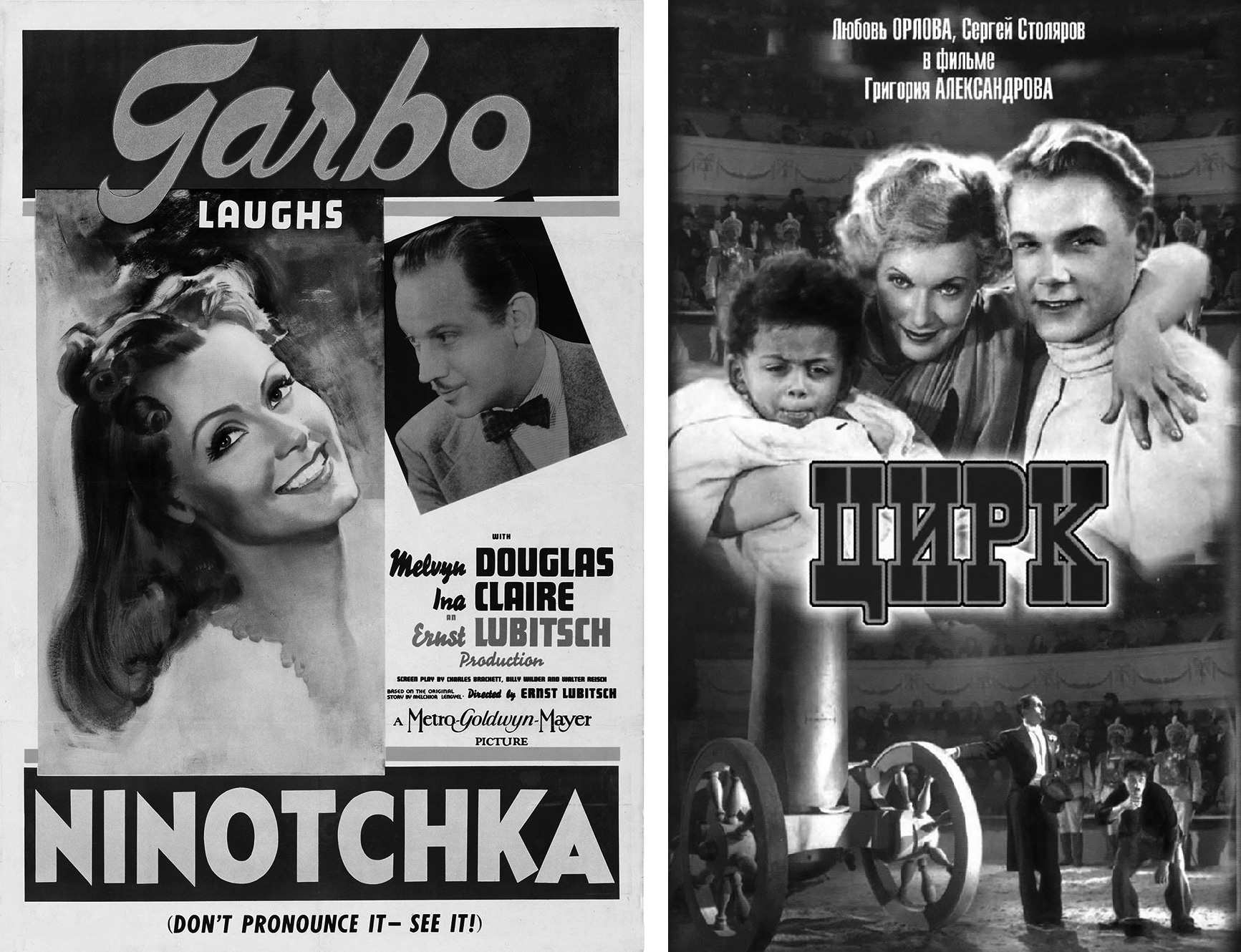

Below–and in conjunction with Sasha Razor’s interview with Vladimir Paperny, which we publish concurrently–we present a translated excerpt from a recently published book Paperny co-authored with noted late Russian film historian Maya Turovskaya, Cinema, Culture, and the Spirit of the Times (NLO: Moscow, 2023). Turovskaya and Paperny began their comparative study of US and Soviet cinema with two comedies: the mildly anti-Soviet Ninotchka and the strongly pro-Soviet film Circus. Ninotchka (1939), directed by Ernst Lubitsch, is a romantic comedy about a stern Soviet envoy, Nina Ivanovna “Ninotchka” Yakushova, who falls in love with a charming Parisian, Count Leon d’Algout, played by Melvyn Douglas. Circus (1936), directed by Grigori Aleksandrov, is a Soviet musical drama about a young American circus performer, Marion Dixon, played by Lyubov Orlova, who falls in love with the troupe’s engineer, Ivan Martynov, played by Sergei Stolyarov. Paperny and Turovskaya’s analysis of these two films demonstrates that despite dramatically different political messages, and almost against the creators’ wishes, both films transmit the universal “spirit of the time.”

From: Vladimir Paperny/Maya Turovskaya, Cinema, Culture, and the Spirit of the Times (NLO: Moscow, 2023).

Film posters. Ninotchka (dir. Ernst Lubitsch, 1939) and Circus (dir. Grigori Aleksandrov, 1936).

The film Ninotchka was born from a plot conceived by an immigrant Hungarian screenwriter named Melchior Lengyel. His plot consisted of three phrases: “A Russian girl imbued with Bolshevik ideas finds herself in frightening capitalist Paris. There she finds love and falls into a whirlwind of pleasure. Capitalism, it turns out, is not so bad.” Salka Viertel, who had been asked to find a plot for a new Greta Garbo film, decided that this was the right one. She arranged with Melchior that he would try to sell the idea to Greta while she was swimming in her pool. The idea worked. Salka wrote a draft of the script, which was then rewritten many times by different screenwriters — as was the custom in Hollywood studios. Billy Wilder, Charles Brackett, Walter Reisch, and Melchior Lengyel are officially credited as the authors of the script. Neither Lubitsch, who also worked on the script, nor Salka is on the official list.

Billy Wilder was one of Hollywood’s brightest and most successful screenwriters, directors and producers. He wrote scripts for sixty-two films, twenty-six of which he directed, and fourteen of which he was also a producer. He won seven Oscars and countless other awards. He was fourteen years younger than Lubitsch and considered him his teacher. Wilder was born in 1906 in Poland, then part of Austria-Hungary. For a while he worked as a hired dancer in Berlin. He wrote the screenplay for the experimental documentary film Menschen am Sonntag (People on Sunday), which had a significant influence on both German and American cinema. After Hitler came to power, he moved to Paris, where he made the film Mauvaise Graine (Bad Seed) in 1934, and then fled to America. His relatives who had remained in Austria were victims of the Holocaust. It was Ninotchka for which he and Charles Brackett were nominated for an Oscar for best screenplay that brought him success in America. I suspect that the funniest dialogues in Ninotchka were written by Wilder.

There are different versions of Greta Garbo’s participation in this film. According to one of them Garbo was sick of portraying tragic heroines — drowned, crushed, shot, thrown under a train or died of tuberculosis. She told producers that if she is not given to star in a comedy, she will go back to Sweden. When Melchior Lengyel laid out his idea to Garbo, everything turned on. At first, Louis B. Meyer (MGM) was against the participation of Garbo in this film, he doubted her comedic abilities, but when Paramount agreed to rent out for a time its best director Ernst Lubitsch, a big fan of Garbo, Meyer agreed. The complete rapport between Lubitsch and Garbo, according to critics, is what created the “magic of the film.”

According to another version, the capricious and unpredictable Garbo found Lubitsch vulgar. When she arrived at the studio to negotiate, she refused to get out of her car. Lubitsch had to sit in her car for two hours negotiating. After the movie, Garbo complained that the film was unfunny, and working with Lubitsch did not give her any pleasure. On the other hand, her partner Mercedes de Acosta later said: “Never have I seen her in such a happy mood, as during the filming of Ninotchka. She said that for the first time in Hollywood she worked with a truly great director.

The plot of Ninotchka repeats the Lengyel’ scheme, but the writers have added a lot of fun. Commissar Nina Yakushova is sent to Paris. She must find out why the three agents sent there to sell diamonds confiscated by the Bolsheviks from the Grand Duchess Swana have instead rented the most expensive hotel room and are having fun. (Here, as Maya noted, the screenwriters showed foresight in describing the future behavior of post-Soviet Russians abroad.) Agents Iranoff, Buljanoff, and Kopalski meet her at the train station. This comic trio is somewhat reminiscent of the American Marx Brothers (one reviewer jokingly called them the “Karl Marx Brothers”). It does not occur to them that the commissar could be a woman. In the scene on the platform, the screenwriters’ jokes and Lubitsch’s virtuoso mise-en-scènes are playing out this wrong gender assumption.

The three agents rush to the first man, who looks, as they think, like a “comrade,” but as soon as the man approaches the woman who meets him, both give the Nazi salute and joyfully exclaim: Heil Hitler!

Kopalski: No, that’s not him…

Buljanoff: Positively not!

Iranoff: We must have missed him!

By now the platform is almost empty. As the Russians in the foreground look around helplessly, we see in the background a woman who obviously is also looking for someone. The Russians exchange troubled looks and go toward her. The woman comes forward. As they meet she speaks.

Ninotchka: I am looking for Michael Simonovitch Iranoff.

Iranoff: I am Michael Simonovitch Iranoff.

Ninotchka: I am Nina Ivanovna Yakushova, Envoy Extraordinary, acting under direct orders of Comrade Commissar Razinin.

Iranoff: What a charming idea for Moscow to surprise us with a lady comrade.

Kopalski: If we had known we would have greeted you with flowers.

Ninotchka: Don’t make an issue of my womanhood. We are here for work… all of us. Let’s not waste time. Shall we go?

Iranoff: Porter!

Ninotchka (dir. Ernst Lubitsch, 1939) Buljanoff, Iranoff, and Kopalski meet the Commissar: Ninotchka: (to Porter) Why should you carry other people’s bags? Porter: Well… that’s my business, madame. Ninotchka: That’s no business… that’s social injustice. Porter: That depends on the tip.

Ninotchka: (to Porter) Why should you carry other people’s bags?

Porter: Well… that’s my business, madame.

Ninotchka: That’s no business… that’s social injustice.

Porter: That depends on the tip.

Circus (dir. Grigori Aleksandrov, 1936). Mary, a white woman with a black child, runs from a racist mob in the U.S. South. At the last moment, she manages to jump onto a departing train. She runs into the compartment where the German entrepreneur von Kneischitz is sitting.

The film was shot at the same time as Ilf and Petrov were traveling in America. The absence of the writers gave Aleksandrov the opportunity to rewrite the script in his own way. Isaac Babel was invited to help with the script, as had already happened with Eisenstein’s Bezhin Meadow. Upon returning from America, Ilf and Petrov saw the almost finished film and demanded that their names were not in the credits. As a result, the film came out without the authors of the script at all — quite an unusual situation in the cinema. At the same time, Aleksandrov received payments for the script, which caused the indignation of Ilf and Petrov.

Circus begins with a prologue, the action of which takes place somewhere in the South of the United States. The first thing we see is a page of the local newspaper with a headline (first in English, then in Russian) “Sensational Scandal. Marion Dixon is a Projectile Woman.” Below, under a picture of Orlova as Marion: “Marion Dixon is responsible for the greatest scandal in history.”

The scene of meeting the heroine, as in Ninotchka, involves a train. Marion Dixon, a white woman, gives birth to a black child. An angry mob runs after her shouting, “Beat her!” Marion, with the baby in her arms, manages to jump onto the departing train. She collapses into the compartment where the German entrepreneur von Kneischitz is sitting, exhausted. The train mysteriously brings them to the USSR.

The prologue mimics 1920s American cinema. The paradox is that the shooting style here is indistinguishable from Eisenstein’s Strike, a film in which Aleksandrov participated as both screenwriter and actor. The so-called “Russian montage” — by Kuleshov, Pudovkin, Eisenstein and others — markedly influenced American cinema in the 1920s. In 1936 Alexandrov brought this style back to the USSR, but now the style represents America.

Strike (dir. Sergei Eisenstein, 1925)

Circus (dir. Grigori Aleksandrov, 1936)

Alexandrov knew America and its cinema well. Together with Eisenstein he participated as a screenwriter in a failed collaboration with Paramount Studios and an equally unsuccessful collaboration with Upton Sinclair’s company, working on a film about Mexico. Eisenstein had to return to Moscow on Stalin’s orders; Aleksandrov stayed for another year. As Maya wrote, “Eisenstein came to teach Hollywood the revolution, and Aleksandrov became a diligent student of Hollywood.”(Maya Turovskaya, “Circus & Ninotchka” (unpublished article, reproduced in Vladimir’s book).)

From the prologue we learn that the career of Marion, the “shell man,” began in America. In the USSR, she would repeat her circus act first with Kneischitz and then with director Martynov, whose love for him would force her to change ideology. In her case, among other things, it will be a renunciation of religion – before her first performance at the Moscow Circus, she is baptized, the Catholic way, from left to right, and in her makeup box we manage to spot a crucifix. The atheist Aleksandrov seems to have made a mistake here. The woman from the American South is most likely a Baptist. Baptists, like most other American Protestants, do not make the sign of the cross, much less carry a crucifix.

To quote Maya again:

As the engine of the plot — the flight of an American circus star from the West — the director chooses the most effective argument of Soviet prewar propaganda: racial segregation. Marion Dixon’s black child nearly makes her a victim of lynching and then puts her at the mercy of the exploiter-entrepreneur Kneischitz, as if to multiply American racism by German fascism in the image of the West.(Ibid.)

Ninotchka’s first encounter with the French Count Léon d’Algout, takes place while crossing a street in Paris. The Count is played by the famous actor Melvin Douglas. He was born in America, but his father was an immigrant from Latvia. Leon is a charming slacker and lover of the Grand Duchess Swana, at whose expense he seems to live. There is a dialogue between representatives of two almost incompatible civilizations:

Ninotchka: You, please.

Leon: Me?

Ninotchka: Yes. Could you give me some information?

Leon: Gladly.

Ninotchka: How long do we have to wait here?

Leon: Well — until the policeman whistles again.

Ninotchka: At what intervals does he whistle?

Leon: What?

Ninotchka: How many minutes between the first and second whistle?

Leon: That’s funny. It’s interesting. I never gave it a thought before.

Ninotchka: Have you never been caught in a similar situation?

Leon: Have I? Do you know when I come to think about it it’s staggering. If I add it all up I must have spent years waiting for signals. Imagine! An important part of my life wasted between whistles.

Ninotchka: In other words you don’t know.

Leon: No.

Ninotchka (dir. Ernst Lubitsch, 1939) Ninotchka: I have heard of the arrogant male in capitalistic society. It is having a superior earning power that makes you like that. Leon: A Russian! I love Russians! Comrade… I have been fascinated by your Five-Year Plan for the past fifteen years! Ninotchka: Your type will soon be extinct.

Ninotchka: Thank you…

Ninotchka: I have heard of the arrogant male in capitalistic society. It is having a superior earning power that makes you like that.

Leon: A Russian! I love Russians! Comrade… I have been fascinated by your Five-Year Plan for the past fifteen years!

Ninotchka: Your type will soon be extinct.

The first meeting between Marion, or Mary, and the engineer Martynov takes place in a Moscow circus. The resourceful von Kneischitz has managed to recreate Marion’s American number, a cannon flight to the moon, and at the same time to fall in love with her. Martynov is also impressed, he is struck by her athleticism, dancing and singing in both Russian (with a charming accent) and English:

Ya iz pushki v nebo uidu!

(from the cannon into the sky I will go!)

How do you do, How do you do!

It’s love at first sight. Martynov snatches the bouquet from the hands of the bewildered Shurik Skameikin and throws it to Mary, flying around in a circle on a metal “moon.” Mary takes a rose out of the bouquet and throws it back to Martynov. The declaration of love has taken place.

Circus (dir. Grigori Aleksandrov, 1936)

In both films, the scene of the first kiss begins with a view of the city from above: in one, the view of Paris at night from the Eiffel Tower, in the other, the morning view of Red Square from the Moscow Hotel. The dialogue between the emotional and eloquent Leon and the rational Ninotchka ends with a passionate kiss at his home. Ninotchka takes this kiss as physical therapy. As Maya observes, “The comic image of the commissar from Moscow is derived more from the Soviet mythology of female equality of the ’20s than from the pragmatic ’30s.”

Ninotchka (dir. Ernst Lubitsch, 1939) At the top of the Eifel Tower. Leon: You must admit that this doomed old civilization sparkles… It glitters! Ninotchka: I do not deny its beauty, but it is a waste of electricity!

Leon: You must admit that this doomed old civilization sparkles… It glitters!

Ninotchka: I do not deny its beauty, but it is a waste of electricity.

Ninotchka (dir. Ernst Lubitsch, 1939). At Leon’s house.

Leon: Oh, Ninotchka, Ninotchka, surely you feel some slight symptom of the divine passion… a general warmth in the palms of your hands… a strange heaviness in your limbs… a burning of the lips that is not thirst but a thousand times more tantalizing, more exalting, than thirst?

Ninotchka: You are very talkative.

Leon (kisses her): Was that talkative?

Ninotchka: No, that was restful. Again.

Circus (dir. Grigori Aleksandrov, 1936). Moscow, Red Square.

In Circus, the kiss never happens. Martynov teaches Mary the official Soviet song “Wide is My Motherland.” A black maid enters the room and whispers something to Mary. A baby can be heard crying. It is a black son, the existence of which Mary tries to conceal, believing that her “sin” will not be forgiven in this country either. Her fear is cynically exploited by von Kneischitz, frightening her into revealing the secret if she does not respond to his advances, which, of course, do not involve marriage.

Lest Martynov guess anything, Mary rushes to the piano and begins to play loudly the melody she has just learned with boisterous virtuoso accompaniment, trying to drown out the baby’s cries. Aleksandrov replaces the kiss required by the situation with a “gag”: overflowing with emotion, Martynov runs out onto the balcony, and his wings grow out — an ironic tribute to silent cinema. The kiss will not take place in the film at all.

Circus (dir. Grigori Aleksandrov, 1936)

The transformation, or, in Soviet parlance, the “re-education” of Ninotchka begins with a laugh. When in 1930 Garbo starred in Anna Christie, her first sound film in, the advertising campaign was built around the slogan Garbo Talks! Ninotchka, where Garbo laughs for the first time on screen, demanded another slogan: Garbo Laughs! Leon tries to cheer her up with the funniest jokes he knows. Ninotchka listens without expression, but when Leon sways irritably in his chair and falls to the floor, she bursts into uncontrollable laughter. As Maya has written, the wisdom of Lubitsch, a born comedian, seems more prescient than the film’s message: along with Leon’s unshakeable gentleman image, Ninotchka’s defensive line of sovietness collapses — laughter liberates, it is irreverent to any dogma.

The next stage of Ninotchka’s transformation is connected to clothing. Whereas Mary embraces collectivity through love, Ninotchka embraces love through liberated individuality. The intricate “bourgeois” hat she noticed in a shop window at first bewilders her. ”

Ninotchka (dir. Ernst Lubitsch, 1939)

Ninotchka: What’s that?

Kopalski: It’s a hat, Comrade, a woman’s hat.

Ninotchka: How can such a civilization survive which permits women to put things like that on their heads. It won’t be long now, Comrades.

Ninotchka (dir. Ernst Lubitsch, 1939). After Meeting Leon Ninotchka secretly buys the hat. We hear the main lyrical theme by the film’s composer, Werner Heimann — another crew member who escaped Nazi Germany.

Ninotchka’s final reconciliation with luxury occurs before her forced return to her homeland. She dances with Leon at an expensive restaurant in a lavish dress, then, after a few glasses of champagne, as Leon is reported, she gives a “propaganda” speech in the women’s bathroom, then both, barely able to stand on their feet, return to her hotel. Ninotchka takes the tiara of the Grand Duchess Swana out of the safe, puts it on, and gives another speech.

Ninotchka (dir. Ernst Lubitsch, 1939) Ninotchka: Comrades! People of the world! The revolution is on the march… I know… wars will wash over us… bombs will fall… all civilization will crumble… but not yet, please…wait, wait… what’s the hurry? Let us be happy… give us our moment…. We are happy, aren’t we, Leon?

After this, Ninotchka falls asleep, forgetting to lock both the door and the safe. The hotel clerk “from the old days”, a loyal monarchist, steals the jewels and returns them to Swana. In the morning the jealous Swana gives Ninotchka an ultimatum: if Ninotchka leaves for Moscow immediately, the jewels will be returned to her. Guilt and responsibility to her homeland force Ninotchka to take the jewels, give up her love, and fly away.

Mary’s “re-education” takes place in the opposite direction. She wants to give up luxury and become “like everyone else.” It is only by losing her exceptionalism that she becomes Soviet. As Maya wrote, “in cameraman Vladimir Nielsen’s elegant work, the motif of transformation is shown through a gradual transition from black to white, for example, from a black artificial wig to natural blond hair and bright white sportswear, the ideal of socialist utopia”(Ibid.)

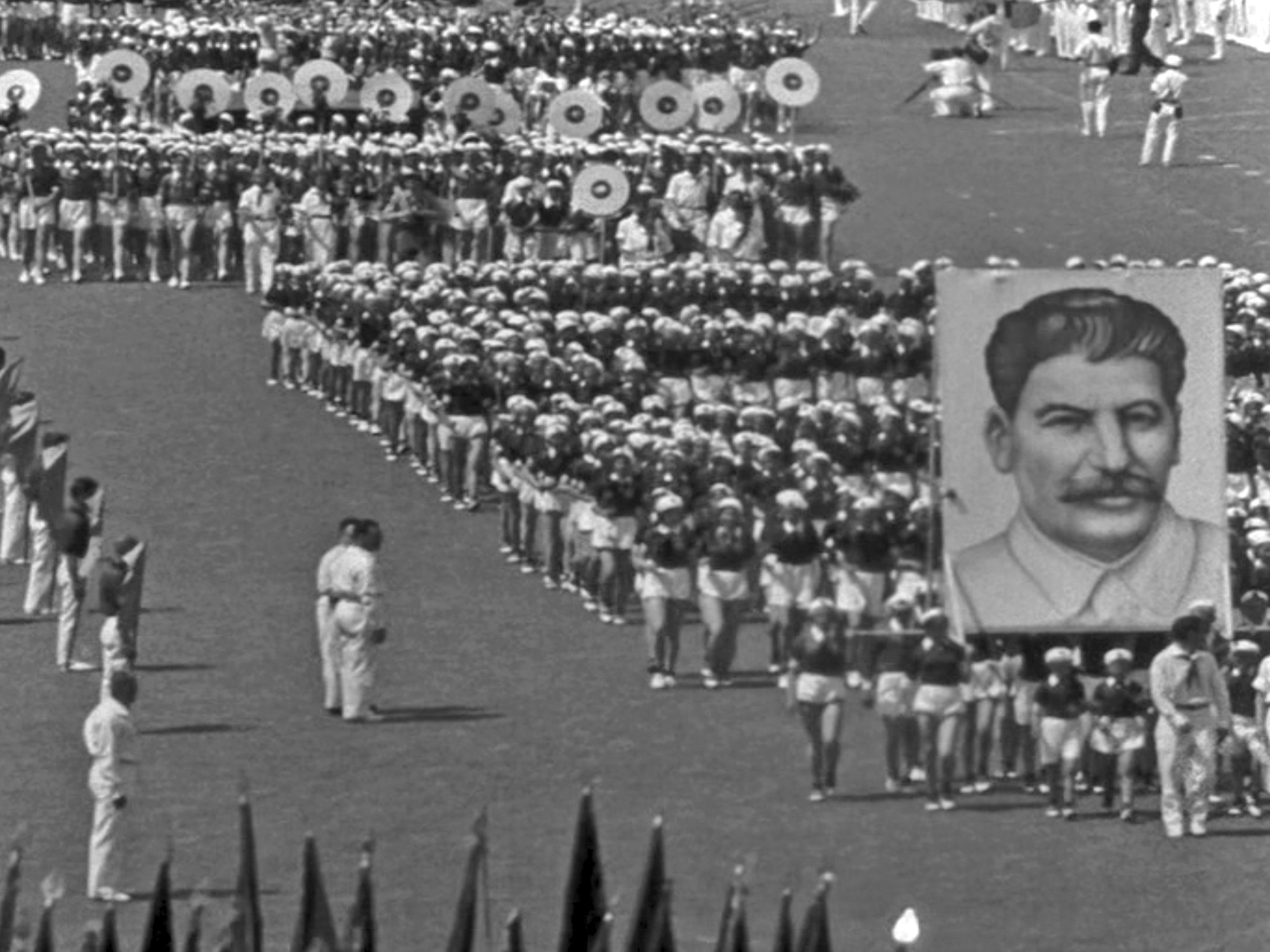

Circus (dir. Grigori Aleksandrov, 1936). A man’s voice-over sings: I don’t know another country where people can breathe so freely…

Circus (dir. Grigori Aleksandrov, 1936). Mary (in accented English): I want to stay in Moscow! Kneischitz: People don’t marry someone like you, but I… All these things I bought for you, Mary! Mary: That Mary is no more!

Circus (dir. Grigori Aleksandrov, 1936). The official demonstration on Red Square in Moscow. Mary experiences the joy of looking like everyone else.

Can “Ninotchka” be considered an anti-Soviet film? Does the film portray the Soviet Union truthfully? These questions have been discussed since the film’s release and continue to interest critics to this day. On the one hand, there is Salka Firtel’s memoir: “Ninotchka was in full production, Lubitsch came to my office every day and told me that despite his bitterness about the Stalin-Hitler pact, the film was not anti-Soviet.”

“The film is so kind and toothless,” says film historian Ted Sennett, “that it should be considered more of a friendly parody than a serious satire.” It’s true, Ninotchka is not a satire. It is a comedy. The screenwriters joke even about Stalin’s terror. When Kopalski asks Ninotchka how things are going in Moscow, she replies: “Very well. The last mass trials were a great success. There are going to be fewer but better Russians.” Of course, victims of Stalinist terror and their descendants might find such humor blasphemous. Although I am one of those descendants, I disagree. Parodies and witticisms, my father’s for example, helped the transformation of Soviet consciousness as much, if not more, as dissidents’ texts. “All our skepticism and cynicism about the Soviet power,” Maya told me, “would never have been realized and articulated without your father’s (Zinovy Paperny) jokes and parodies.” Because laughter, as she wrote elsewhere, is “irreverent to any dogma.”

The idea of the film’s “toothlessness” is refuted by the Soviet reaction. Soviet diplomats tried to put pressure on movie theater owners in Vienna not to show “Ninotchka,” and as counter-propaganda placed ads for the Soviet patriotic film The Fall of Berlin on Viennese billboards. The same thing happened in Rome. The film also was banned in Estonia and Lithuania (under Soviet pressure), in Bulgaria (under German pressure), in Italy (under Fascist pressure) and in France (under French Communists’ pressure, though for a short time).

As for credibility, the two professors, Michael Strada and Harold Topper, did not find it in the film: “Don’t look for information in Ninotchka about what really happened in the USSR at the time,” they wrote. “You won’t find that there. If the main characters look one-dimensional, then the image of the country does not even that.” This, in my opinion, is a misunderstanding. The creative company of Hungarian, Austrian, German and other refugees from Nazism managed, in the form of a “toothless parody,” to recreate the atmosphere of Soviet life without leaving the “light genre”.

In Circus, we saw a quotation from an American movie. In Ninotchka, we see an almost literal (though parodic) quotation from a Soviet movie.

Circus (dir. Grigori Aleksandrov, 1936). The Parade on Red Square

Ninotchka (dir. Ernst Lubitsch, 1939). The Parade on Red Square: Lubitsch imitates Aleksandrov?

Ninotchka (dir. Ernst Lubitsch, 1939). IIn Ninotchka’s communal apartment in Moscow. The four of them sing: I still love you, Paris! I still dream of you!

Commissar Razinin: Those three have been sitting there for six weeks and haven’t sold a piece of fur. Buljanoff, Iranoff, and Kopalski, get so drunk that they throw a carpet out of their hotel window and complain to the management that it didn’t fly. You are going to t Constantinople immediately!

Ninotchka (dir. Ernst Lubitsch, 1939). Commissar Razinin: Buljanoff, Iranoff, and Kopalski have been sitting there for six weeks and haven’t sold a piece of fur. Those three get so drunk that they throw a carpet out of their hotel window and complain to the management that it didn’t fly. You are going to to Constantinople immediately!

Ninotchka is sent to put Iranoff, Buljanoff and Kopalski on the right path. The drunkenness of the trio was strategically orchestrated by Leon. He calculated that Ninotchka would be the one sent to instruct them on the right path. When they meet Ninotchka in Constantinople, Iranoff, Buljanoff and Kopalski invite her to their own restaurant. Ninotchka is shocked. “Have you become traitors to the fatherland? Who gave you that idea?”

Appears Leon. Iranoff, Buljanoff and Kopalski delicately leave them alone. Leon tries to persuade Ninotchka to stay.

Leon: If you do not stay, I will continue the struggle. I will travel to all the countries where there are representatives of Russia. I’ll turn them all into Iranoff, Buljanoff and Kopalski. The whole world will be covered with Russian restaurants. There will be no one left in Russia.

Ninotchka (dir. Ernst Lubitsch, 1939). Ninotchka: Well, if I must choose between my personal interests and saving my country, what doubts can there be! No one can say that Ninotchka was not a patriot!

Circus (dir. Grigori Aleksandrov, 1936). Mary marching and singing in the column of demonstrators next to Martynov: Wide is My Country

Ninotchka: Well, if I have to choose between my personal interests and saving my country, what doubts can there be! No one can say that Ninotchka was not a patriot!

Mary marching and singing in the column of demonstrators next to Martynov: Wide is My Country

In the final shots of Circus, we see almost all of the film’s characters among the columns of demonstrators marching through Red Square.

“Now you understand?” Raechka asks Mary, nodding in the direction of the invisible Mausoleum.

“Now you understand!” Mary answers (not quite having grasped the Russian grammar) looking in the same direction.

Circus (dir. Grigori Aleksandrov, 1936).

It’s not hard to guess whose presence at the mausoleum should ensure “understanding.” Perhaps it is for this understanding that both Aleksandrov and Orlova will receive Stalin prizes for the film. Aleksandrov will use the same technique of showing an invisible Stalin in the film The Shining Path (1940). As Tanya-Cinderella receives the Order in the Kremlin, someone invisible shakes her hand, the reflections of the Order appear on her face, and she almost faints, and then dances with an invisible prince in the Kremlin Palace. Although the song says “And Kalinin himself gave the order to Cinderella,” it is impossible to imagine that Kalinin could cause Cinderella to have such ecstasy, almost fainting. Although Kalinin is only three years older than Stalin, he has a different role — he is not a prince, but a “good old grandfather”, while Stalin by definition has no age. Aleksandrov is a master of showing Stalin sneakily. The film Volga-Volga shows giant statues of Lenin and Stalin on both sides of the canal as the steamboat enters the lock. In the 1950s, the shots with the statue of Stalin were cut out, only the side of the ship with the name “Joseph Stalin” written in large letters is left in the film. Words, as we know, became more important than images since the 1930s, so the remaining name of the steamship still sends the message.

Raechka: Now you understand?

Mary: Now you understand!

The Shining Path (dir. Grigori Aleksandrov, 1940). Tanya-Cinderella is awarded an order by someone. A glow emanates from the order. Tanya is close to fainting.

Tanya-Cinderella is awarded an order by someone. A glow emanates from the order. Tanya is close to fainting.

“For Lubitsch,” Maya concludes her unpublished article, “Ninotchka’s straightforward but lofty democratism is somehow nicer than the greedy secularism of the Grand Duchess and her jurors. The woman, as both paintings attest, is the most mobile part of society. And it is not so much the elegant Count who reeducates the naive Ninotchka as she changes the secular fathom, turning him into a man.”

Both films tell more or less the same story. If we were to retell it with the succinctness of Melchior Lengyel, it would sound like this: “The heroine finds herself in a frightening, strange land. There she finds love. New –ism, it turns out, isn’t so bad.” But ultimately the films lead us in opposite directions. Marion Dixon, an American Protestant, having fallen in love with the Russian engineer Martynov, loses interest in consumption, gives up the expensive clothes von Kneischitz bought her, and marches through Red Square in white sportswear, the same as everyone else, in the same column with her friends and her beloved Martynov. Her black child does not have to be hidden anymore, he has acquired a new father, who is also the Father of the Nation. Marion, of course, breaks with religion, because she already “understands” something more sacred, though unnamed — just by looking at the Mausoleum, on which, as everybody knows, stands Stalin himself.

Commissar Ninotchka travels in the opposite direction. She discovers that love is not just “the romantic name for the most ordinary biological process,” as she was taught in the early Soviet era, but also something else. This new feeling she experiences for the first time makes her interested in her own appearance. She secretly buys a frivolous French hat, which until recently seemed to her to be a symbol of a dying civilization. She enjoys trying on the diamond tiara of the Grand Duchess of Swana, which almost leads her to lose her beloved Leon. Most importantly, love brings out her sense of humor, and laughter, as Maya said, is irreverent to any dogma — Ninotchka is now able to parody Soviet formulas: “If I have to choose between my personal interests and the salvation of my country, how can I hesitate!”

Ninotchka (dir. Ernst Lubitsch, 1939).

The very last frame of the film gives the viewer a parting gift of the proverbial “Lubitsch touch.” The three “Karl Marx Brothers” are already involved in class struggle.

Translated by Vladimir Paperny