The Canary Archives by Chto Delat: Testimony of the Russian ‘Des-Astre’

In March 2022, shortly after Russia had attacked Ukraine, the Chto Delat (What is to be done?) collective produced an artwork entitled Canary Archives in response to the shock of the military escalation.(Chto Delat, “Canary Archives 2022,” http://chtodelat.org/category/b7-art-projects/installations/canary-archives-2022-2/ Accessed January 31, 2023) While work on the project – comprising a four-channel video installation and a newspaper issue – had commenced earlier, the invasion was the catalyst for its statement. The filming and written elements were revised substantially as a consequence of the outbreak of war. Today, more than one year later, the relevance of the work has become more clear, and analysis of Canary Archives permits us to address some critical queries that art faces in times of social tragedy. Which artistic languages are legitimate? Are they able to embrace a traumatic experience? Can artists speak out against the war from within the aggressor country, and if so how? Featuring a series of new components in comparison to previous Chto Delat’s works, the piece can be perceived as a breaking point with the past, and as a crucial testimony that can contribute to understanding how memories of the present will be constructed, represented, and archived.

Chto Delat, Canary Archives, 2022. Four-channel video installation, construction fence, wood, newspaper, format variable. Exhibition view. KOW Berlin. Courtesy Chto Delat and KOW Berlin. Photo: Ladislav Zajac.

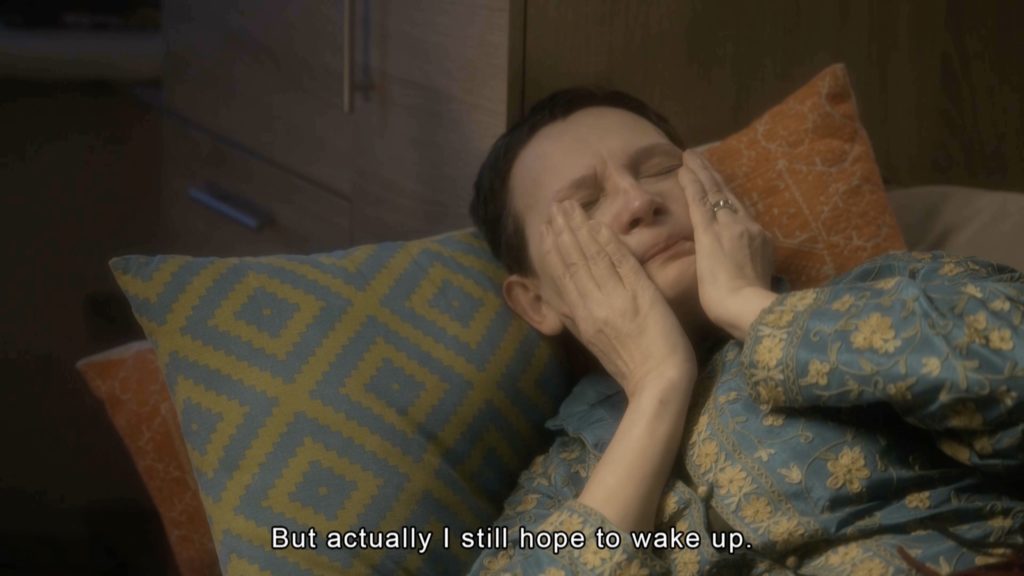

Chto Delat was founded in early 2003 in St. Petersburg by artists and philosophers with the goal of merging political theory, art, and activism.(Chto Delat, https://chtodelat.org/) The collective’s founding members are Olga Egorova Tsaplya (artist), Nina Gasteva (choreographer), Artemy Magun (philosopher), Nikolay Oleynikov (artist), Alexey Penzin (philosopher), Natalia Pershina Glucklya (artist), Alexander Skidan (poet), Oxana Timofeeva (philosopher), and Dmitry Vilensky (artist). The group has always been openly politically engaged and addressed social issues related to the neoliberal order by linking local Russian concerns to the international agenda. The artists’ anti-capitalist and anti-nationalist left position is the reading key to their oeuvre, as well as the clear stance against Vladimir Putin’s regime that cost them persecution and political exile last autumn. The core of Canary Archives, the group’s last project, is the four-channel video made of distinct narratives: an animation of a metal cage slowly crawling down in gloom, accompanied by whisperings and barely audible laments; nine canaries chirping and fluttering in a cage; a minimal choreography by a group of people in the darkness; and close-ups of Chto Delat’s members meditating on their dreams and nightmares.

Chto Delat, Canary Archives, 2022. Four-channel video installation, construction fence, wood, newspaper, format variable. Videostill. KOW Berlin. Courtesy Chto Delat and KOW Berlin.

Chto Delat, Canary Archives, 2022. Four-channel video installation, construction fence, wood, newspaper, format variable. Videostill. KOW Berlin. Courtesy Chto Delat and KOW Berlin.

Commissioned in 2020 by Berlin’s Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW) in the broader framework of the group research and exhibition The Whole Life. Archives & Imaginaries, the work was initially planned by Chto Delat as a study of Georgij Plekhanov’s documents and the development of the labor movement. The aim was to give an alternative view of history and “to rehabilitate the past.”(Oxana Timofeeva, “What Do Canaries in Coal Mines Dream Of. Collective Dialogue of the Members of Collective Chto Delat,” Chto Delat Newspaper, March 2022, https://chtodelat.org/category/b8-newspapers/canary-archives-2022/ Accessed December 28, 2022) The first idea involved investigating the materials contained in the Archiv der Avantgarden (AdA), part of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, and linking them to those of St. Petersburg Plekhanov’s House through a video performance that would build the connection between the distinct archives. This initial plan was abandoned due to the Covid pandemic, which changed the artists’ priorities, and the commissioned work was put on standby. The only activity Chto Delat’s members felt made sense to carry forward was recording testimonies from the social network and private conversations in order to “note down premonitions of the tectonic changes taking place before our eyes.”(Dmitry Vilensky, “Canary Archives. Editorial,” Chto Delat Newspaper) This experience resulted in the second provisory idea to work on – the archive of anxieties related to ecological catastrophes and “the broken connection between humans and the planet.”(Haus der Kulturen der Welt, “Canary Archives – Files of Dreams and Other Matters,” https://archiv.hkw.de/en/programm/projekte/2022/the_whole_life_congress_berlin/ausstellung_the_whole_life/chto_delat_canary_archives_files_of_dreams_and_other_matters.php Accessed January 31, 2023)

From the record of testimonies, a metaphor of a canary in the coal mine emerged, referring to a forgotten practice: workers used to take birds with them into mines to detect noxious gasses before men got sick, knowing that the canaries would stop singing when the oxygen level decreased. The American writer Kurt Vonnegut employed this metaphor talking about the social role of artists in his “canary-bird-in-the-coal-mine theory of arts.”(Kurt Vonnegut, Conversations with Kurt Vonnegut, ed. William Rodney Allen (Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, 1988), p. 76) Vonnegut addressed artists as “agents of change” with the ability to anticipate processes hidden from others: “Writers [and the artists] are a means of introducing new ideas into the society, and also a means of responding symbolically to life”(Ibid). As Egorova remembers: the artists decided to work on the image of a canary, which, as they claim, lives in each of us, alerting us when something goes wrong, and it is time to escape. “It is best to search for this bird on the boundary between reality and dream,” Egorova opines. “When we wake up, and the canary is hammering in our head, we are often in a precarious state and are able to receive the signal. So we have decided to tell each other our dreams and wait for the canary to appear.”(Conversation with Olga Egorova and Dmitry Vilensky, archive of Yulia Tikhomirova, January 12, 2023) Several video interviews and other preparatory material developing this idea had been produced; however, when the war started, the artists realized that “all their canaries were dead.”(Ibid) Chto Delat’s members admit their failure to anticipate the coming tragedy: “Our canary seems to have gone silent (the sharpest and clearest signal it can send), a fact we have discovered too late; and now we are locked in a shaft filled with poisonous fumes.”(Vilensky, “Canary Archives. Editorial”) The artwork suffered the same drastic change as the artists’ lives. The video footage is marked with filming dates associated with an unsettling calendar of before and after the beginning of the war and denotes an insurmountable distance from the previous life.

Chto Delat, Canary Archives, 2022. Four-channel video installation, construction fence, wood, newspaper, format variable. Videostill. KOW Berlin. Courtesy Chto Delat and KOW Berlin.

The Canary Archives film renounces several of Chto Delat’s acclaimed methods and recognizable traits of its stylistic code. Among the missing features, the first to catch the eye is the typicality of the characters who face concrete historical events and are representative of social contradictions, like it was, for example, in the group’s well-known songspiels. The term songspiel was first used by the German playwright Bertolt Brecht and composer Kurt Weill regarding the opera Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny (1930), meaning a song-play or a scenic cantata that employed both singing and reciting parts. In Brecht’s songspiels, dichotomies of social and economic mechanisms were revealed through a combination of popular music, clear character types, minimalistic but incisive scenery, and a plot generated by the specific political case. A similar task Chto Delat had in mind for its films – to make the mechanisms of the capitalist machine visible. They would take a real social case, investigate its causes and consequences and exhibit its simplified model, structuring it as an ancient tragedy with the dramatis personae divided into a chorus and a group of heroes (or anti-heroes) with typical characteristics. At the intersection of radical theater, contemporary art, and pedagogy, this approach aims to show that capitalism and social injustice have political roots and need to be seen historically to fight against, thus dismantling the capitalist myth of the natural order of things. Chto Delat’s performances originate precisely from the “exhibit of the contradictions” inherent to the epic, dialectic, or materialist theater.(Walter Benjamin, “What is Epic Theater?,” in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt (New York: Schocken Books, 1969), p. 149) Its method – the self-conscious narrative rather than a realistic embodying of the events on stage – grants primacy to a theater play’s influence on spectators to activate the transformation of real life.

Among others, the didactic Brechtian approach can be traced in Chto Delat’s Perestroika, Partisan, Tower, or Museum songspiels, where the oppressors and the oppressed are not identified by personal names or biographies but are representatives of specific social strata and interests.(Chto Delat, Perestroika Songspiel (2008), Partisan Songspiel (2009), The Tower. A Songspiel (2010), Museum Songspiel (2011), http://chtodelat.org/category/b8-films/ Accessed January 31, 2023) The films clearly reveal their theatrical construction and political statements to avoid illusionism and emotional identification of the public with protagonists and, instead, to make spectators reflect on the reasons behind the narrative. By entrusting acting to external collaborators – actors, artists, and activists – Chto Delat has mostly stayed out of the frame, taking care of staging, directing, and editing. In the Canary Archives video, though, we encounter all nine founding members as performers. Oleynikov states it was a conscious decision: “It became clear that Chto Delat should not speak using the voices of the younger generation. Now, at the time of war, it seemed honest to us to speak with our own bodies, words, poetics, and thoughts and stay in the video frame as exposed as possible.”(Conversation with Nikolay Oleynikov, archive of Yulia Tikhomirova, May 18, 2022)

Chto Delat, Canary Archives, 2022. Four-channel video installation, construction fence, wood, newspaper, format variable. Videostill. KOW Berlin. Courtesy Chto Delat and KOW Berlin.

The film shows artists as individuals in their private interiors, “grayer, stouter, such as they are, getting out for the first time to act in a video,” representing no one but themselves.(Conversation with Nina Gasteva, archive of Yulia Tikhomirova, September 29, 2022) The immediacy, imminence, and horridness of the present did not allow the collective to have an overview of the situation and face it with a cold rationale of accurate political research. The critical approach to reality expressed in a visual outcome mixing surrealistic, situationist, and operatic features – Chto Delat’s successful method – would look pretentious and self-celebrating in the current circumstances. Regardless of aesthetic value, an artistic response to a tragedy that does not imply a revision of language but only a change of subject matter is not capable of reflecting a traumatic experience and can only be an opportunistic move. The artists confess they could not address the situation by applying their usual methods: “The reality has gone out of its way. It is not like it has become obscure – it has become alien. That is why we have started to look for new tools to deal with this reality.”(Conversation with Egorova and Vilensky)

Chto Delat, Canary Archives, 2022. Four-channel video installation, construction fence, wood, newspaper, format variable. Videostill. KOW Berlin. Courtesy Chto Delat and KOW Berlin.

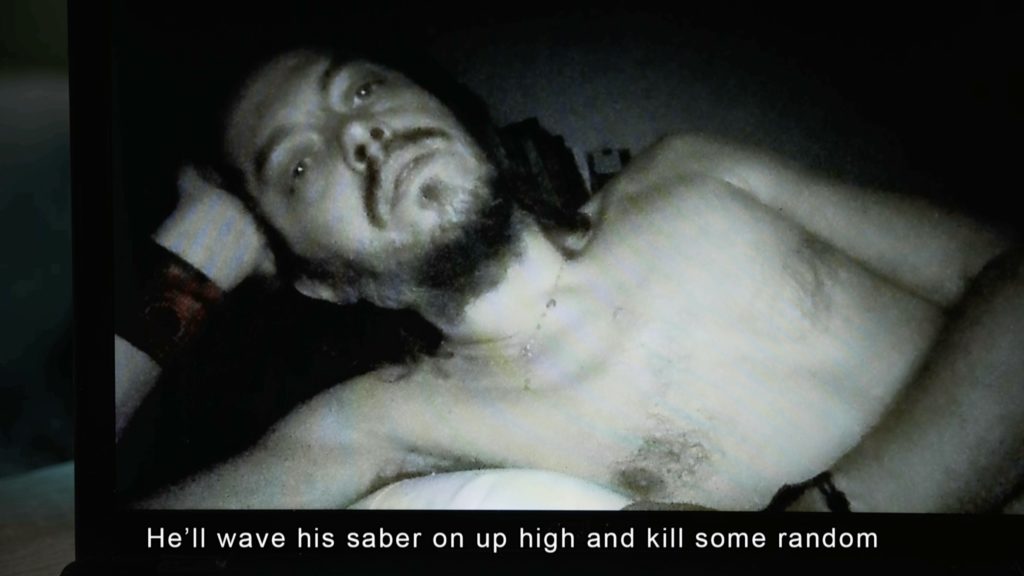

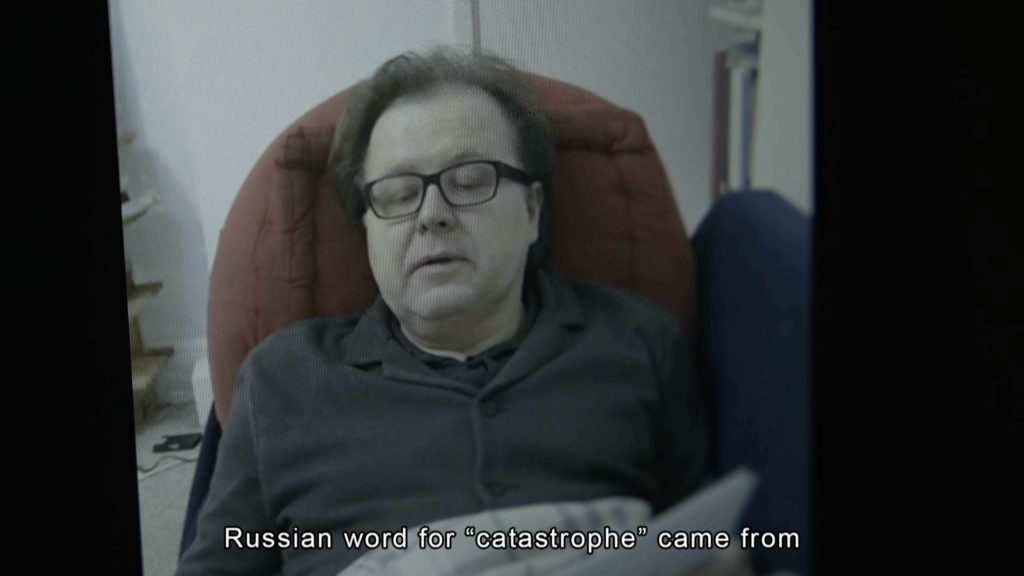

While on one of the four screens of the video the mine elevator descends further and further into the shaft, on the other we encounter the collective’s members – each on an imaginary underground level, lying in bed as if just woken up. As Gasteva recalls, the shooting process was a new landmark; the collective spread in different countries, people were abandoning their houses, and life intermingled with fiction: “Everyone had some personal circumstances behind the shooting frame. We did not want to make a tragic film, but it happened anyway.”(Conversation with Gasteva) Visually disconnected and isolated, filmed from a close intimate distance, the artists talk “about themselves, about their (night)dreams, about the catastrophe, about the war, about poetry, about how one got to where one is now.”(Alexander Koch, “Canary Archives, Chto Delat”, KOW, https://kow-berlin.com/exhibitions/canary-archives-files-of-dreams-and-other-matters Accessed December 10, 2022) The personal monologues combine the oniric language of premonitions, hallucinations, and fears with philosophical reflections and expressions of civil position. However, words fail, and rationality does not manage to keep people on the surface as the elevator proceeds, bringing them deeper underground. The real tension is not in words – one can easily miss parts of the low voice discourses – but behind them, in the gestures, the synchronicity of forms, almost static choreography, and birds’ turmoil.

Chto Delat, Canary Archives, 2022. Four-channel video installation, construction fence, wood, newspaper, format variable. Videostill. KOW Berlin. Courtesy Chto Delat and KOW Berlin.

The bodily expressions and their liaison to the speech have always been central to Chto Delat. The two languages do not compete: each has its function and works according to its dynamics without illustrating or annulling the other. The estrangement effect employed to keep the spectator alert was inherited first from Bertolt Brecht and then from Jean-Luc Godard and is often expressed through the separation of languages. The purpose is to create some extra space “so that there is no direct access to the story, so that this access, resulting more complicated for the audience, would knock the viewer out of his usual perception.”(Conversation with Gasteva) In the case of the Canary Archives video, the estrangement effect prevents the viewer from perceiving the content exclusively on the emotional or rational level, splitting the attention between inputs. The sounds and movements on separate screens create a “shimmering distance between the viewer and the character, and between the character and his movements,” bringing us back to our own position as spectators.(Ibid) We stay aware that we are watching an artistic construction and must take a stance toward it critically.

The film deals with deep, bodily voices and minimal sound instead of the Soviet musical realistic tradition present in other collective’s videos. A similar sound operation was already implemented in the artwork The Excluded. In the Moment of Danger (2014): the formation of a new collective body carried forward by the excluded at the time needed a brand new sign system (gestural and phonal) to express their dissensus and protest against mainstream chauvinist rhetorics after the annexation of Crimea.(Chto Delat, “The Excluded 2014,” Chto Delat, http://chtodelat.org/category/b8-films/the-excluded-in-a-moment-of-danger/ Accessed January 31, 2023) In the Canary Archives film, the experiment goes further: the affirmative pathos is gone, and the weak sounds that arise before the speech have to do with the artists’ capacity to perceive rather than to profess. These pre-sounds are connected to the almost indiscernible dancing shown on one of the split screens: figures, in a group or alone, dressed in yellow plaids, with torches on foreheads, move in the darkness. Their gestures “create a volume for ideas, meanings, and bodies, for presence itself,” as Gasteva describes, “when the usual language has faded away and has become blurry.”(Conversation with Gasteva) Regarding this vanishing process, in one of the film episodes, Penzin reflects on the etymology of two words – disaster and catastrophe – and how the perception of the abstract terms changes under the pressure of reality. “Disaster is ‘des-astre.’ It means no stars. Pitched darkness. […] Catastrophe is borrowed from the Greek word katastrophḗ which means literally turn, coup, reversal or possibly denouement,” meditates the philosopher, noting that the terms have dimed their linguistic boundaries in the situation of direct experience.(Chto Delat, Canary Archive, four-channel video installation, 06’10”, https://vimeo.com/710686637 Accessed December 10, 2022) The film shows this concrete knowledge, impossible yet to apprehend, as the eternal process of descending, as “an endless, dizzying fall,” revealing “the bottomless depth of the unconscious […], where memories of what has not yet been and a premonition of what has already been are compressed, becoming one substance.”(Oxana Timofeeva, “Nightmare,” Chto Delat Newspaper)

Chto Delat, Canary Archives, 2022. Four-channel video installation, construction fence, wood, newspaper, format variable. Videostill. KOW Berlin. Courtesy Chto Delat and KOW Berlin.

Remarkably, this visual metaphor reminds us of the pit of Babel, mentioned in an enigmatic note by Franz Kafka, which the artist Hito Steyerl refers to in her essay “The W(hole) of Babel.”(Hito Steyerl, “The (W)hole of Babel: Magic Geographies of the Global,” Haussite.net, http://www.haussite.net/haus.0/SCRIPT/txt2001/01/s_babel.HTML Accessed December 11, 2022) The pit excavated deeply in the ground is the opposite of the monumental tower of Babel, which, as the legend suggests, caused the loss of the language common to all humankind. Steyerl argues that the idea of global communication revives the Babylonian dream of universal dialogue. Nonetheless, according to her, it has been built on local contradictions, contested borders, and racist differentiations. In the Canary Archives film, the mine shaft acts as a negative of the tower, functioning through absence and sightlessness and “providing no general outlook at all, but merely the faint possibility to make a connection.”(Ibid) Whereas on the ground level, the language has failed, the labyrinthic experience of descending to the unknown could be read as “the possibility of a different and probably subterranean universal communication.”(Ibid)

Besides typicality and musical realism, Chto Delat renounces the Aesopian language it has implemented for years to address current political issues while evading the harsh censorship artists are subjected to in Russia. The group’s works have adopted metaphorical vocabulary to use against authorities and to communicate with the accomplices. This was the case, for example, of the Russian Woods (2012) film and installation made at the moment of Putin’s run for a third term and the beginning of the mass protest and intensifying repressions.(Chto Delat, “The Russian Woods 2011–2014,” Chto Delat, http://chtodelat.org/category/b7-art-projects/installations/a_3/ Accessed January 31, 2023) The Russian Woods was based on fable analogies and approached political realities by comparing social strata with representatives of the animal world or some hybrid creatures. As far as the Canary Archives film is concerned, the political metaphor is gone. At the time when the Russian government abuses the language, violating the words’ meanings, the Aesopian satire would look out of place, probably offensive, and definitely useless. Chto Delat, thus, proposed the only linguistic operation that made sense in the first days of war: to call things by their names out loud.

Chto Delat, Canary Archives, 2022. Four-channel video installation, construction fence, wood, newspaper, format variable. Exhibition view. KOW Berlin. Courtesy Chto Delat and KOW Berlin. Photo: Ladislav Zajac.

Both the Canary Archives video and the related newspaper issue express the need for a new language: the one to use to be understood by others, the one to abandon because of its obsolescence, the one to invent anew. However, what works in the film succeeds less in the articles: the rationality of written reflections appears shallow and crashes against the ongoing catastrophe. Texts and collective dialogues produced before and after the war create a confusing juxtaposition, showing how insuperable the distance between the past and the present is; the commentary feels abstract and lacks the directness and empathy of the film.

The Canary Archives installation, including the four-channel video and the newspaper, has been exhibited on various occasions and has altered its set-up each time. Throughout its activity, Chto Delat has stressed the importance of the critical use of technology and displays, naming the production protocol as one of the essential points for the collective’s artistic subjectivity. The group’s exhibitions often suggest a mutable nature and are far from being once-decided fixed structures. The same artefacts may wander from show to show, acquiring new meanings thanks to the constellations they shape in connection to other objects and reacting to the concrete display conditions, geographical places, and political agenda. The Canary Archives project follows a similar path. Its first installation was presented in April 2022 in Berlin’s Haus der Kulturen der Welt, where the visitors could watch the four-channel video by entering a metal cage with wood logs as seats in the middle of a big bright hall. The floor was covered with newspaper pages, the issues of which were distributed freely outside the cage. The four screens were hung on different levels of the grid, and the canaries’ chirping, orations, and the noise of the shaft intermingled with birds’ voices from an adjacent room where Godard’s Le livre d’image was exposed, as Egorova recalls.(Conversation with Egorova and Vilensky)

A similar set-up was developed for the KOW gallery in Berlin, where the project was exhibited in July, yet with a significant adjustment: the room with the cage was immersed in darkness, and the sound resulted emphasized. The whole environment was free from any other artwork or scenery (except for the newspapers and the wood logs), and the attention was focused on one spot – the metal cage and four screens that were the only light source. While it could be argued that this display risks overloading the emotionality of perception, and the artists showed some doubts about the choice, the gallery director Alexander Koch, who has been collaborating with Chto Delat for more than ten years, is convinced the decision was timely:

There is not much emotion in the film. You see people talking; what they say is sometimes funny, a bit intellectual, or sad on the private level, but there is no emotional drama. However, as you go on watching, you comprehend the metaphor of the birds, which are there to indicate when the oxygen goes out, and you know they will die just before you die. So you start to understand how existential and dangerous the moment is and that maybe there is no way to imagine the next day because the future perspective is unavailable. Sitting in a dark room, alone with yourself, you relate to the people on screen and feel with them. You have the strongest emotion because the things do not come up as emotional drama but are very dry and factual.(Conversation with Alexander Koch, archive of Yulia Tikhomirova, January 23, 2023)

Chto Delat, Canary Archives, 2022. Four-channel video installation, construction fence, wood, newspaper, format variable. Exhibition view. KOW Berlin. Courtesy Chto Delat and KOW Berlin. Photo: Ladislav Zajac.

In October 2022, the project was shown in Sweden in the Skövde Konstmuseum as part of a joint exhibition with another Russian collective, The Party Of Dead. The Canary Archives installation was again exhibited in plain light but with further arrangements. All the elements were moved slightly in relation to each other and out of intersection axes. The overall composition lost its fixed balance, and the sound was lowered. Egorova argues that the artists tried to avoid any pathos and spoke from a weak position: “Everything was weak there: the voices, the birds tweeting. The composition seemed to be shifted. The confusion we still continued to feel at that time, the loss of language and the construction of a new language were visible. We departed from something slightly crumpled, and there was no such strong energy or emotion as in the KOW gallery.”(Conversation with Egorova and Vilensky)

For public projections, Chto Delat uses the one-screen version of the film, which at first glance may seem more didactic and less involving; however, it hides a strong potential. We constantly face three video narratives in parallel – the life of canaries, the group pantomime in the darkness, and the close-up of an artist in bed. The fourth video of the elevator cage separates the artists’ monologues, pulling the viewer deeper into the depths of the earth with each new character. Different scenes match and accompany each other, the movements and sounds get suddenly synchronized, and the rhythm changes between proximity and sequencing. Here, in these connections, in between the scenes and in the choreography of movements, the artwork happens and acquires its integrity.

The one-screen version, without additional scenery, was publicly shown twice – in Belgrade’s (December 2022) and Sarajevo’s (January 2023) cultural centres. The artists confess that these occurrences were challenging for them as the public they were facing “had survived the horrible war and had suffered it in their bones, in their skin.”(Ibid) The work got a touching reception: people were very moved, and the debates were engaging. What is important to underline here, considering the “monstrous dose of reality” the people present at those screenings had undergone during the Yugoslav wars, is that the Canary Archives film is not about the war.(Susan Sontag, “Tuesday, and After. New Yorker Writers Respond to 9/11,” The New Yorker, September 24, 2001, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2001/09/24/tuesday-and-after-talk-of-the-town Accessed January 31, 2023) It does not meditate on the war experience or claim to comprehend what it can mean. The artists witness, from their position – within the aggressor country – and from their time: “We testify that we are still alive, this world exists, and for us, it looks like this. It seems that now this is the only honest way to speak.”(Conversation with Egorova and Vilensky)

The Canary Archives project is material for the future, adding to the picture of the current tragedy and our present. Historically, in situations of war, repression, or terror, personal diaries, chronicles, and other unofficial sources have played a decisive role in understanding the past and imagining the future. Similarly, Chto Delat’s film is a fragile archive, testimony to the conflict between the invasion of reality, resistance to accepting it, confusion, horror, and inability to distance or withdraw into oneself. On the pages of the Canary Archives newspaper, Timofeeva meditates on the “underground as a hiding place in times of war,” stating that “retreating into the depths of a dream serves as a hiding place, protecting us from a more traumatic reality.”(Timofeeva, “Nightmare”) However, the film narrative precludes any possibility of escape: the characters continue to descend into the earth’s bowels, to the core of what seems to be a pit rather than a shelter.

Now, a year after, the work functions already as evidence from the past, remote and gone, since the war has accelerated the temporal length of events. “When cannons speak, the Muses are silent – this old rule has always been challenged by both art and thought, which retained the ability to speak, overcoming muteness. We, therefore, have a chance to remain human,” states Vilensky in the same newspaper issue.(Vilensky, “Canary Archives. Editorial”) The collective ‘we’ used by Vilensky addresses the artistic community. As he opines, in the situation of ethical and political impasse, art can be fruitful for expanding imagination, rethinking one’s position, redefining concepts, and shifting established boundaries, if approached as a practice of empathy.(Conversation with Egorova and Vilensky) From a temporal gap, we can better perceive this emphatic layer of the film – the search for forms and signs capable of interpreting and transmitting the given reality. The Canary Archives’ artistic language starts from a weak, unconfident position, confusion, and crumpledness and is pronounced by vulnerable, hesitant, mumbling voices. The denunciation is as vital as consolation, especially in the place where the war came, but also where it came from. “The public is not being asked to bear much of the burden of reality,” commented Susan Sontag, speaking against the manipulative rhetorical unanimity propagated by the media in the aftermath of 9/11.(Sontag, “Tuesday, and After”) In times of crisis, political forces try to transform formal and linguistic polyphony into a single voice and exploit it for a specific cause. Instead, what Chto Delat did in the Canary Archives project was to bear as much reality as they could at the moment when they faced it by ascribing artistic legitimacy to testimony and empathy.