One on One: The Didactic Wall (2019) by Mladen Miljanović

The “One on One” series presents timely encounters between ARTMargins Online editors and contemporary artists, usually focused on one recent work.

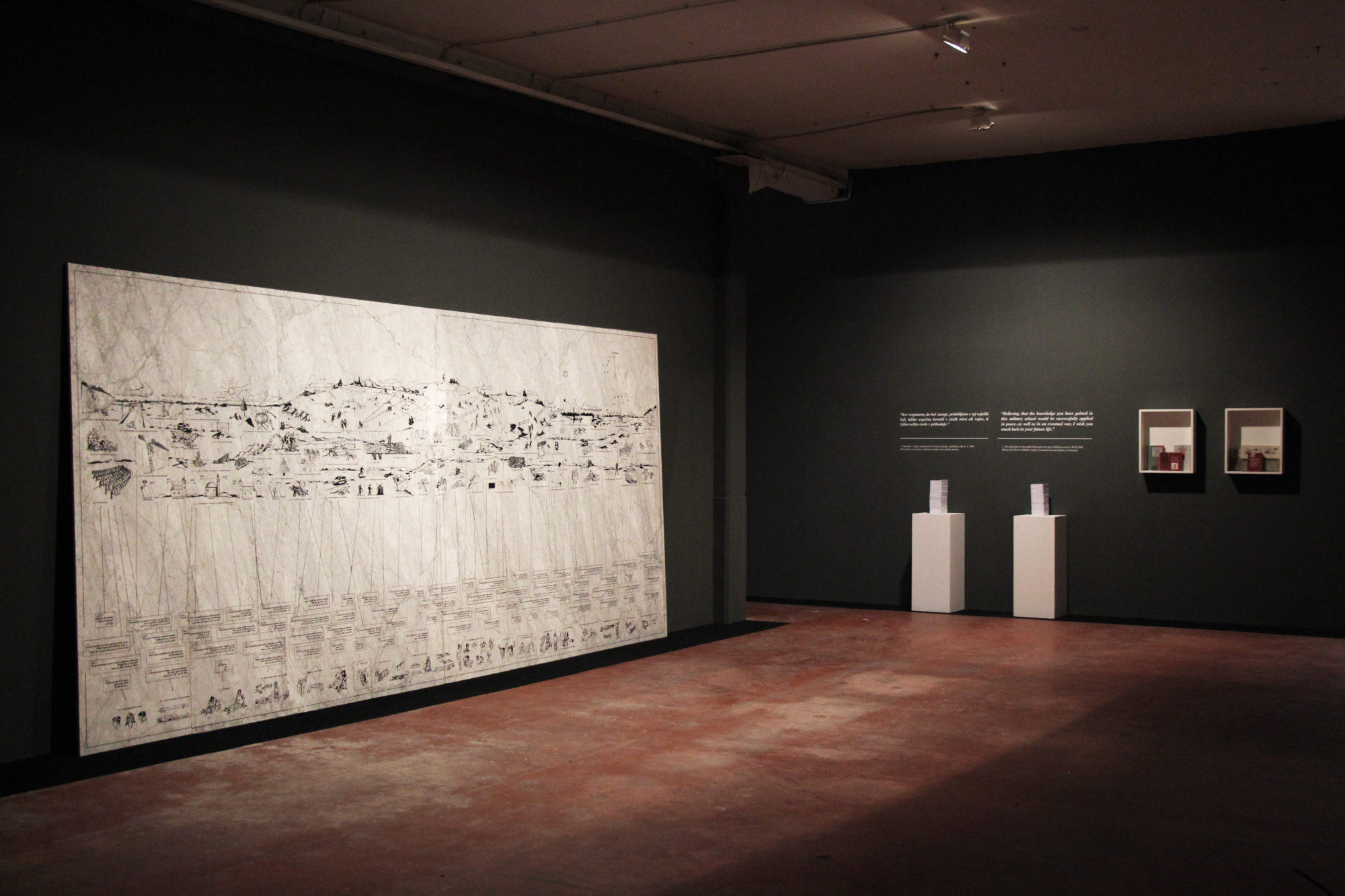

Sven Spieker: Your Didactic Wall (2019) focuses on the issue of migrants, refugees, and displaced persons. The location of the project in Bihać, Bosnia and Hercegovina, is crucial because Bihać is very close to Slovenia. When Croatia closed its borders, thousands of migrants who were hoping to reach Slovenia and, from there, Northern Europe, got stuck. Why did you decide to create an installation in the form of a stone wall?

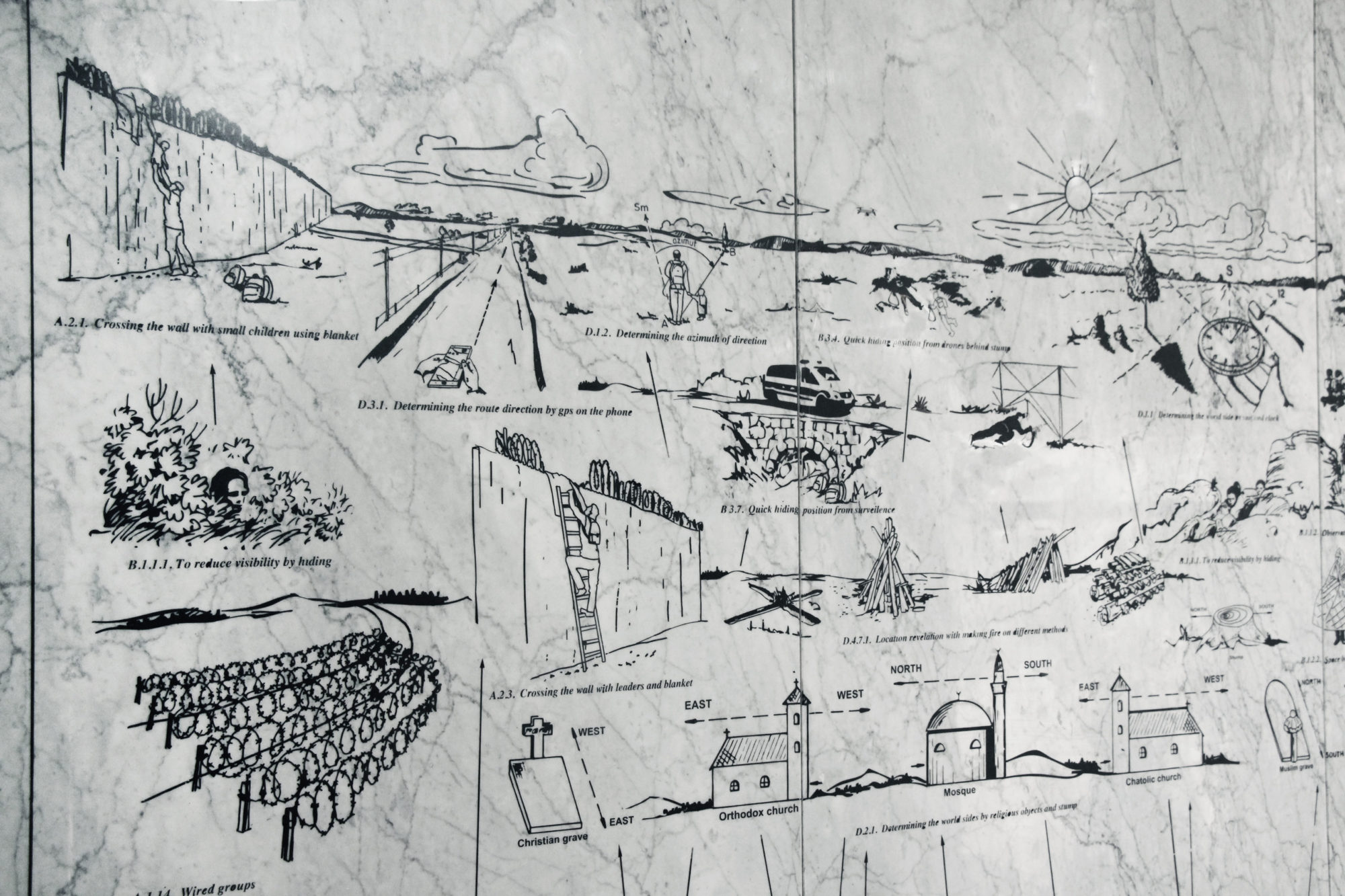

Mladen Miljanović. Didactic Wall, 2019. Engraved drawing on marble. Installation detail.

Mladen Miljanović: There are two main reasons that initiated the realization of this work. The first was frustration with the lukewarm and almost imperceptible reaction of the entire cultural and art sphere to this situation. And the second reason was the idea of questioning the possible educational, didactic and humanistic role of art and its intervention and reaction in such situations.

Returning to the first reason, there have been exhibitions that dealt with this topic, but in most cases, they were geographically located at a great distance from the focus of the problem, and that is as if you have a fire burning in the kitchen and you douse the garage. The next thing is that the content of the works presented at such exhibitions in most cases only illustrated or aestheticized the situation, exploiting the predicament of these people without any feedback in regard to their hopeless situation. So, this work is focused on how to act tactically and educationally in relation to this situation through art. Bihać became a regional center for people on the move, and it began to look more and more like Tijuana or Calais.

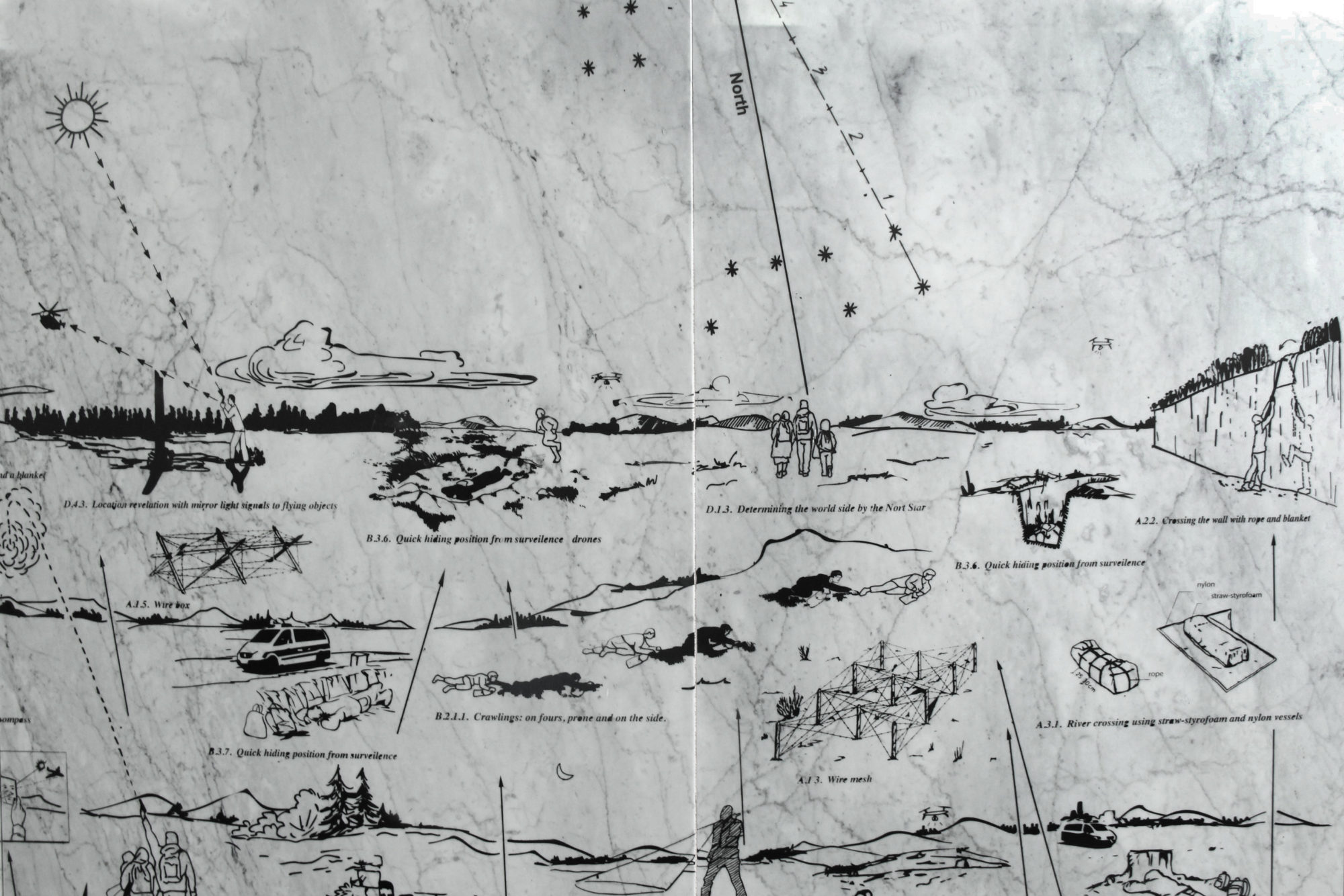

Mladen Miljanović. Didactic Wall, 2019. Engraved drawing on marble. Installation detail.

On the other hand, naming the wall “didactic” transforms it from being an obstacle into being a tool for overcoming obstacles. The work is not about overcoming “a” wall, but about overcoming walls with the help of a didactic wall. This is significant for deconstructing Bihać as synonymous with “wall,” and that is why in his descriptive text, the curator of the show, Irfan Hošić, defines the work as site specific.

SS: Does art more generally have an educational function for you?

MM: Yes. One of the dictionary of “didactic” says that it is “the art of teaching.” In my work I have been particularly interested in emphasizing the cognitive, educational, and emancipatory role that art could have in society. On the one hand, there is an abstract aspect to art that is vague, foreign, and often off-putting to people outside the art context. On the other hand, there is the populist pictorial banality that only reproduces reality, and thus its understanding remains within the boundaries of that same reality, endlessly perpetuated. My Didactic Wall experiments with the language of art, which seeks to infiltrate “naked life” (Agamben’s term), and at the same time to help shape it.

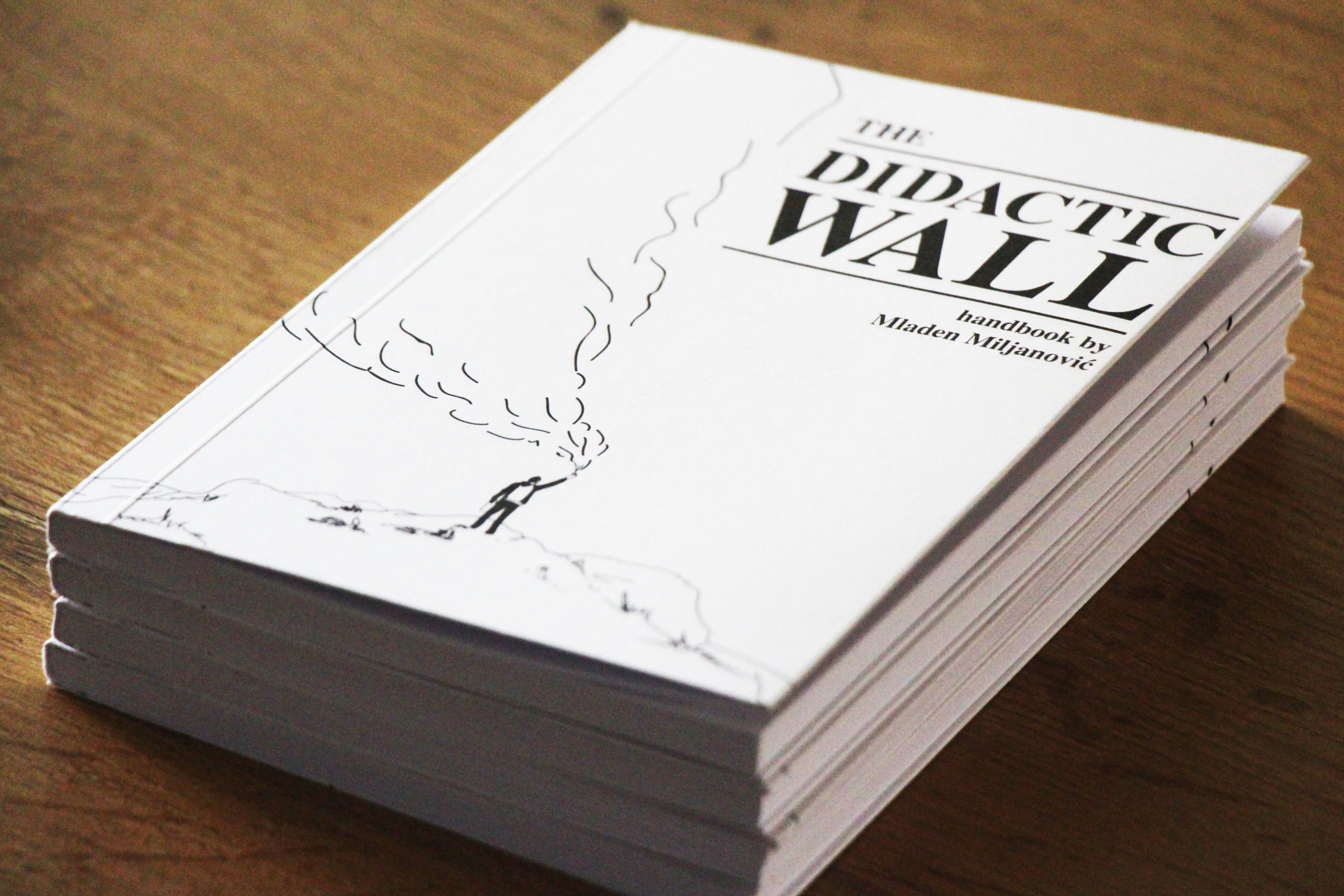

Mladen Miljanović. Didactic Wall, 2019. Handbook.

SS: The booklet that accompanies your installation is based on a handbook from the former Yugoslav People’s Army, containing instructions on how to make oneself invisible, scale walls and other obstacles, and even use the booklet itself as flare. Military knowledge and technique—think of painted camouflage—has always included an art component. Should artists think more tactically?

MM: Today, artists necessarily need to think tactically, but I would add, also strategically. Working with different social contexts, every art project is necessarily a strategic project. Because if your work works towards the public, or within the public, it is inevitable that you need to develop the skills of tactical and strategic action, using all of the artistic arsenal you have. The military uses art much more than is commonly thought, yet somehow the same is not the case the other way around. Well, I’m interested in the way in which art may make use of things military. Art and the military are intertwined multiply; it’s no coincidence that the term avantgarde, i.e. artistic and scientific practices that act and think ahead of their time, has its origins in military terminology where it refers to small and elite military formations that move ahead of the rest of the army, breaking through enemy lines.

Mladen Miljanović. Didactic Wall, 2019. Billboard outside of Bihać.

Besides, I grew up 1km from the frontline during the Yugoslav civil war in the 1990s. While children my age were assembling Lego, I already knew how to disassemble and assemble a rifle or a pistol, to distinguish different calibers of bullets, or artillery weapons. While other children my age attended the birthdays of their friends, I hung out with my peers at the funerals of those who died in the conflict. So, I felt on my own skin the uncontrolled and inhumane implications of military knowledge and weapons. We must demilitarize knowledge in all its aspects as much as possible, and art should use demilitarized tactics to redefine the idea of freedom.

SS: In these times of the COVID-19 crisis when we are expected to follow all sorts of rules for the common good, does your Wall want to teach us not to be so obedient?

MM: Desperate situations require desperate measures! In de-integrated Eastern Europe, no one was able to create art from what they desired, only from what they had at their disposal. In these often very limited circumstances, art was created to offer alternatives or to overcome such limitations, whether these are restrictions of one’s personal freedom or social marginalization. The Didactic Wall deals with erasing borders and restrictions on several levels. One of these levels is the restriction of knowledge. We rarely think about it, but military knowledge is generally a closed zone whose percolation into the civilian sector is severely restricted and controlled. My Didactic Wall manual, which uses illustrations and instructions from a Yugoslav military handbook (labeled a “military secret” at the time of the Yugoslav People’s Army) and injects it into the civilian context, seeks to erase the line between military and civilian knowledge. If we want to talk about freedom, we must first talk about the freedom to know.

Mladen Miljanović. Didactic Wall, 2019. Engraved drawing on marble. Installation detail.

SS: Formally, your installation is a diagram that combines text with drawings, and abstraction with more figurative representation. Is this combination a reflection of Bosnia and Hercegovina’s legacy of Christian and Muslim cultures (you use Urdu in your booklet, raising the issue of translation as another crucial investment of your project)?

MM: The visual didacticism of the work is evident; it strives to achieve the transfer of knowledge to the observer as quickly and directly as possible. The drawings present a series of difficult situations, and the caption explains how such situations can be overcome. There is also the horizontal division of the Wall’s composition into “first aid” in the lower part of the wall, and “tactical strategic movements and orientation” in the upper part. The simplicity of the work bypasses the complexity of Bosnia and Herzegovina; its multilingualism emphasizes an aspiration towards a universal understanding of freedom. Unfortunately, we are not currently witnessing the expansion of freedom, and this is another additional motive to contribute and accumulate knowledge that contributes to overcoming our limitations in both the physical and the linguistic realm. My project proves that when systematic solutions are failing, private initiatives may succeed.

SS: How do you think it will translate into different contexts outside of Bosnia and Hercegovina?

MM: The primary and basic place of intervention for this work is the city of Bihać. After the work was presented there, and after the first edition of the Didactic Wall manual was printed, I was certain that it would be shown in other places as well. The condition for presenting the work in other places, however, was that we needed a higher number of manuals. Three editions have been reprinted so far, and the work has been shown in two other places in the region since its first presentation at the City Gallery in Bihać in July 2019. So, it is still circulating in the territory relevant for it. For each of these iterations, an educational billboard with a set of illustrations was set up in Bihać, on the road by which large numbers of people travel towards a better future.

The conversation was conducted over email in June 2020, and lightly edited.

Download the Didactic Wall Handbook as a pdf