“The Soros Center was a Perfect Machine”: An Exchange between Aaron Moulton and Geert Lovink

The following exchange, over email, between Dutch media theorist and Internet critic Geert Lovink and Aaron Moulton occurred on the occasion of the exhibition The Influencing Machine at Galeria Nicodim in Bucharest, which closed on April 20, 2019. The show, curated by Aaron Moulton, was an anthropological investigation into the macroview of the Soros Center for Contemporary Art (SCCA), an unprecedented network of art centers that existed across twenty Eastern European capitals throughout the 1990s. A survey of historical and contemporary artwork that explored ideas of influence, revolution, colonialism, and cultural exorcism, the Bucharest exhibition included a large archive covering the SCCA network that allowed first-time research into the institutionalized strategies of curatorial practice in the early years of the SCCA network, trajectories of influence that lead to specific kinds of cultural production.

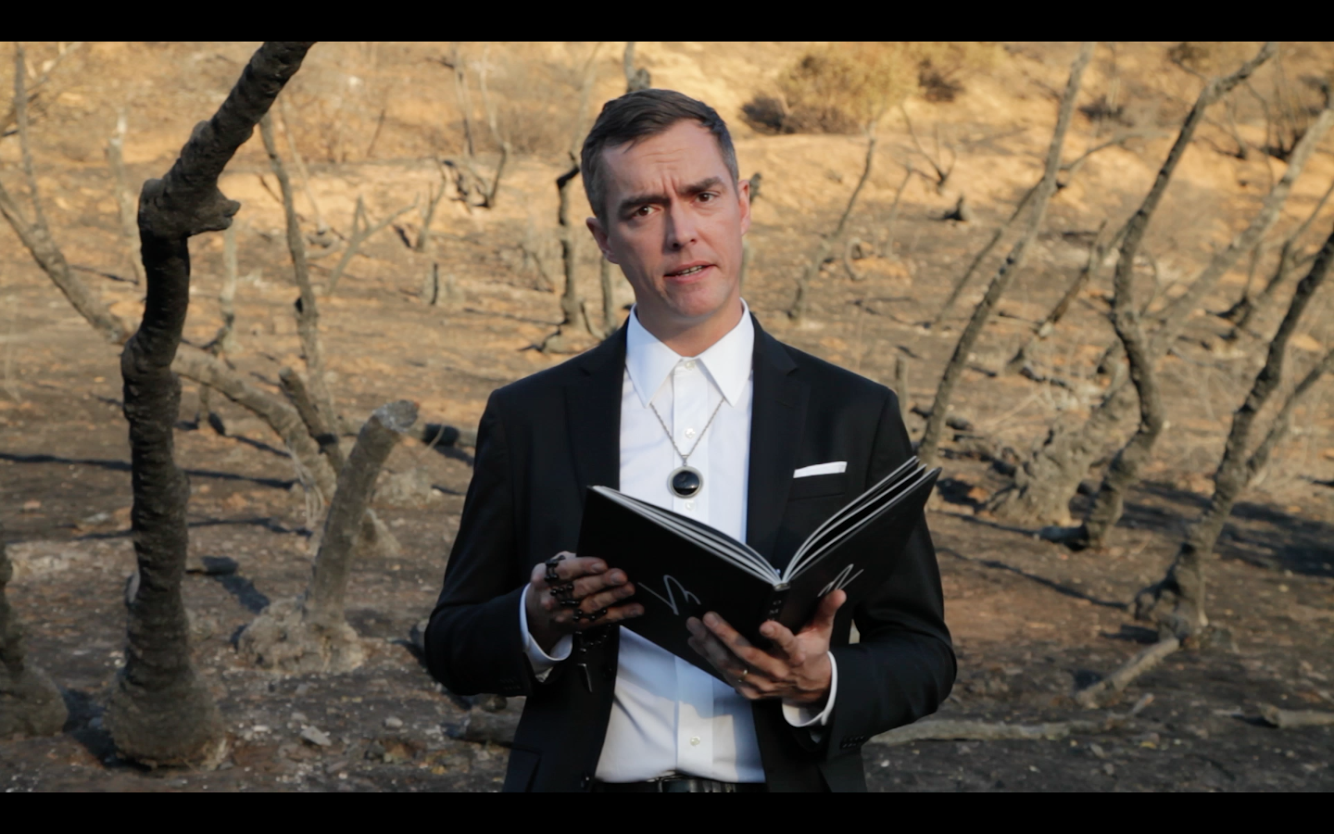

Installation view of “The Influencing Machine”. Galeria Nicodim, Bucharest. Photograph courtesy of Dan Venzentan.

Aaron Moulton: In our panel, you said the following: “The SCCA had to be set up instantaneously because artist unions with their traditional structures were in crisis and nobody expected them to do anything. This was an instantaneous alternative, not something you build up in five or ten or twenty years. Some months after Suzy Meszoly arrived, the SCCA opened and the practice was happening. In that sense it was an activist undertaking. In the years after the fall of communism, people did not sit down and write policy papers first. That would have been a very different approach, to have a long-term vision. Whereas this was done overnight.”

There is something seductive about viewing the SCCA enterprise through a history of propaganda, nestled right there, in between the CIA’s interest in Abstract-Expressionism during the Cold War and the 2016 Russian Trolling of the American elections. It becomes more about the tactical weaponization of visual culture, but in ways less obvious to our usual triggers for understanding how propaganda works with visual culture, i.e. fascism or socialist realism. And in this respect, it is more about being able to witness beta-testing and experimenting with unpredictable results. I somehow see the SCCA as more like a privately funded neoliberal PSYOP.

Taking this all into account, could you reflect on your early role in the SCCA and the development and application of your ideas around tactical media? Obviously, the SCCA was an experimental space for pushing things, but I wonder if the use-value of that work and its successes and failings looks differently when refracted through this lens, especially thinking about it today within the evolutionary narrative of weaponized aesthetics.

Geert Lovink: Let’s travel back thirty years ago. I encountered the Internet for the first time in August 1989. As a thirty-year-old editor of the Dutch media arts Mediamatic magazine, I took notions such as cyberspace, virtual reality, and the “second self” with me in my luggage when I left Amsterdam and visited Romania, for the first time, in early 1990, two months after the fall of Ceausescu. No doubt there was a “ground zero” atmosphere in the air. However, my encounters with the Eastern Bloc date back earlier. I visited Prague, Budapest, and East Berlin throughout the 1980s and made friends there. The critique of “real existing socialism” was important for me, as was the study of Stalinism. As an anarchist squatter, I never had any sympathy for communist rulers. My politics at the time was probably comparable to that of Michel Foucault: I was—and still am—suspicious of any type of power. But how can such a radical position not render you incapable of acting?

In regards to the SCCA exhibition, if I were to position the work of Soros and the Open Society Institute, I would stress the minority position in Eastern Europe of Western progressive liberalism back then (and even now). The idea that this was a hegemonic force that simply moved in after communism collapsed in order to claim supremacy is simply not the right image. Is neo-liberal globalism what people wanted after they had done away with communism? There was no desire for globalization. What started to flourish on the ruins of communism was nationalism and xenophobia in all shapes and sizes, the return of religion, and the return of communist officials as democratic neo-liberal politicians.

It was a privilege for me to work in the SCCA context as I was neither an American nor of East European descent. Inside SCCA, your background mattered. The national identity question was implicitly present, even in this context. Passports matter anyway. The American presence was perceived as something real. The EU was weak and divided and had no clue about all these different countries and people. The British, French, Spanish and the Italians showed no interest and left Central Europe to the Germans and Austrians. This was a Europe before Maastricht, Schengen, and the Euro: weak, deindustrialized, and in permanent recession.

At the time, I used to speculate about what it would mean to go beyond a fixed retro-identity and design. Not just radically new identities but also artificial heritage where history no longer is that fateful burden one carries and has to escape from, but where it becomes a fluid space of possibilities. At the time, Eastern Europe was going in the reverse direction: a proto-regression state of what we now experience everywhere. I experienced this as a return to nineteenth-century Europe when liberation and emancipation were closely related to the rise of ethnic nationalism. We thought that history was a nightmare you wanted to escape from. It seemed such an odd anomaly to desire to go back in time in the age of the Internet, globalization, and the EU. This made the experience even more exotic, like traveling in a time machine (which is, of course, the wrong metaphor to start with). Our collective, Adilkno, wrote about this in an essay titled “Reality Park Romania,” a reference to the rise of reality TV, virtual reality, and the desire among Westerners to have “real” experiences in an authentic offline setting.

It is too easy to state that the Open Society project was merely facilitating the import of the neo-liberal ideology of globalization. However, this is simply not true, as the work of Soros, and our work, was to fight the last war against authoritarianism. Soros always stressed the importance of Karl Popper’s Open Society and its Enemies (whereas I would have brought up Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism in that context, as both were published around 1950). Freedom of movement, for minorities, and freedom of speech were not a joke, they were—and are—vital, in particular for the arts. In my understanding, this freedom would not primarily be a legal framework, and here I differ from the constitutional line of Soros and other “civil society” NGOs. Freedom cannot be defended by lawyers; it is worthless if it exists only in the form of a constitution on paper. If you’re in court, you’re already too late. For us and from day one, it had to be embodied in a lively culture of real existing diversity and dissent that would thrive on ideas, controversies, and debate. A lived and expressed freedom, not one that is merely secured by institutions.

It is in this context of lived freedom that I locate the SCCA network. It is cynical to say that contemporary art has only prepared the ground for capitalist expropriation and exploitation. If you blame yourself for gentrification, then you’re on the wrong side anyway. To ask why this billionaire, George Soros, would support this kind of contemporary art is to ask the wrong question. He was convinced to do so by people around him (such as Suzy) who told him that liberty had to be embedded in a culture with an explicit political and social context in order to prevent white cube elitism and instrumentalized state art. “Difference” wasn’t just a fashionable French philosophical concept that postmodern thinkers and feminists were fooling around with. Democracy, if it was to have any chance in Europe, would have to be a lived, shared experience, both mediated and embodied, with the aim to push the boundaries of aesthetics and perception.

Besides these larger societal contexts, there was the rise of (new) media. The possibilities to build up new media arts/activism infrastructures, institutions, and practices in Eastern Europe coincided historically with the arrival of the personal computer and laptop, the spread of video recorders, satellite TV receivers, as well as xerox and fax machines—all of them cheap consumer electronics produced in Asia. That’s the material base of what is called “tactical media.” In the early 1990s it was primarily video, but tactical media quickly expanded to include multimedia and eventually computer networks.

The question of why one would side with a Wall Street billionaire was discussed back then as well. This is obvious, also taken my anarchist-autonomous squatters background (in the early 1990s I again lived in a squat in Amsterdam). The answer was pretty straightforward: it was a classic case of a Gramscian historical compromise against the reactionary nationalist forces. In the early 1990s, freedom of the press in Cluj, Sibiu, andBucharest meant reprinting fascist and ethno-nationalist nostalgic journals and books. The return of nationalism, anti-semitism, and authoritarian rule in Europe after 1989 was overwhelmingly visible. Once the threat of the Soviet army was contained, violence was in the air, and it was anticipated to come from within.A few months after my first visit to Romania I was beaten up by neo-Nazis in East-Berlin (this was right before German reunification). A year later the civil war started in the former Yugoslavia, a bloody conflict that dominated the entire 1990s—not just my own political activities, but also those of the SCCA network, operating as it did during its entire existence in the shadow of the greatest armed conflict in the history of post-war Europe.

Soros was by no means the only American charityfoundation that was active in Eastern Europe in the 1990s. He operated on the liberal side of the spectrum, however from a European perspective he was fairly mainstream. This also explains Soros’ initial support for Orban and Fidesz.

But in post-communist Eastern Europe, these “liberal” positions had different meanings. For a good part of the past decade, there were no (green) “leftist” or even social-democratic positions, let alone new parties with such a signature. There was a “civil society,” meaning it was neither nationalist nor post-communist. The big threat came, and still comes, from the ethnic and nationalist right-wing (sometimes disguised as post-communist)—that is in reality a pro-Russian, local mafia that privatized state assets for themselves and successfully dismantled state sectors that took on neo-liberal “market” positions. All this was not done by Soros’ book—or Brussels’s, for that matter. With this inevitable corruption came a dislike for “openness,” and then things turned from bad to worse: media censorship, authoritarian rule, anti-semitism, and resentment against refugees.

AM: Why in your mind is it too easy or even improper to interpret the SCCA legacy as a colonial one? History tells us this time and again when we look back. When thinking about the role of lobbying within our trusted institution, it would seem cynical to not question the motives of the SCCA or Soros himself. Would you not say that the SCCA bureaucratized the political nature of their activities in the name of art? From the nurturing of meta-revolutionary discourse to the degree to which artists were encouraged to engage in bureaucracy, situational interventions, political triggers, and new media tactics involving advertising and other distribution networks. There are distinct moments of activism stimulated and rationalized as art. As former SCCA Chisinau Director Octavian Esanu said to me in a conversation, contemporary art’s true function was as the “watchdog” of culture. In comparison to the previous communist culture or the kind of cultural production that was naturally emerging in Eastern Europe, there was suddenly, with the SCCA, a militaristic sense of the avant-garde as something that will experiment with and discover the boundaries of democracy as well as the potential limits of a NGO’s mission.

GL: Yes, SCCA “imported” certain kinds of art discourses from Vienna, Berlin, London and New York, the ones we can read in Texte zur Kunst, Frieze and Artforum. It was an attempt to connect Eastern and Western art scenes under one ideological umbrella that I would still consider counter-cultural rather than hegemonic. The link with the big money that circulated within the art market simply wasn’t there. Soros’s aim was to establish an “autonomous” art sector that would feed off social-democratic liberal state funds. In the absence of a generous ministry of culture or related funds, Sorosstepped in to fill the gap.

AM: Seeing the program histories of the different SCCAs in those important early years gave me a lot of insight into monitoring the exact moment of influence, i.e. seeing the adoption and adaptation of language/practiceas an emergent behavior in a cultural vernacular across the network. From 1993 to 1994, for instance, there was Polyphony and four other very similar, and arguably autonomous, shows that happened. This was an unlikely velocity (especially for early 1990s museum culture in Eastern Europe), when we consider everything that has to happen for such projects to mature, from the gestation of an idea, its application, to the unprecedented level of bureaucracy each of these shows would generate. It leads me to question whether an institutionalized implementation of this idea was in motion well before Polyphony would emerge as a concept to be then “tested and copied.”

We know the SCCAs required artists to sign a contract specifying that the money they received could not be used for propaganda purposes, for interfering in a democratic election, in legal processes (lobbying), or in promoting a particular political agenda. However, this contradicted the premise of many curatorial frameworks for seminal exhibitions staged by the SCCAs, including Polyphony and Alchemical Surrender. After all, these shows were celebrated for how context and cultural production should be politicized, weaponized. For example, Polyphony’s subtitle in English was “Social Commentary in Contemporary Hungarian Art,” whereas the Hungarian version was “Social Context as Medium in Contemporary Hungarian Art,” both of them quite contrary positions for the kind of (active or passive) roles art should take up in society. The show Alchemic Surrender took place on an active duty battleship in a naval yard in the Crimean Sea in 1994.Both these shows were Cold-War-era efforts to destabilize, reinvent, and apply cultural hierarchies.

Andra Szantos, the adviser for Polyphony and a longtime adviser to the OSI, and Soros himself comment on the idea of “emergence” as a cause or a symptom, ideas which negate the artificial nature in this case of origin . It was unlikely that socially engaged practice would emerge in a place like Budapest, let alone in the unprecedented and militarized way it did. In that sense, Polyphony literally appeared out of nowhere. Even at the Polyphony symposium in 1993 and in the catalog of Polyphony, the editors comment on how unprecedented and unnatural it was, even in its moment of emergence.

What would you say was the vision for the artist and their career in all of this? What about all the criticisms regarding the SCCAs’ colonialism that were being voiced at the time, with their shows actively desecrating/consecrating monuments. I feel these criticisms are never given much agency

GL: Everywhere the bureaucratic reality of the modern art organization is in contrast with the intentions of the artworks on display and the intentions of the artists. This is by no means an East-European issue. Socially engaged art was imported from the West, that’s a fact, and we also say this of post-industrialism and conceptual art in general, including the large “concept” exhibition format with its strong emphasis on the statement of a “star” curator. What I find more interesting are new ways to develop and support subversive and avant-garde art movements that question conditions in society. Can such initiatives thrive entirely on their own? We do not see that happening. The level of self-organization has been declining for decades. Artists are more and more helpless creatures surrounded by assistants, technicians, curators, state bureaucrats, and critics, all of them constantly interfering with their work. The SCCA network, in that sense, was part of a wave of “professionalization” that took over the role of the former artist union.

AM: Can you address the emergent behavior aspect of the ideas being pushed across the system? There is a documented way in which artists capitulated to the SCCA system by changing their practice from painting to new media. But more importantly, there was also the unlikely velocity with which ideas moved across the region, through the SCCA network, through synchronized programming, influencing a certain kind of cultural production.

GL: As in any grant making scheme, no matter how “tactical” and temporary, there are formats and implicit exclusion mechanisms. Needless to say, this network favored experimental art forms that had been hidden or straight-out forbidden. Experimentation had to be done through very specific channels. This was a contradiction, as “freedom of expression” should have applied to the choice of both medium, content, and style. But this did not happen. Very soon a specific type of SCCA artist began to emerge, known elsewhere as the “biennale artist,” trained and domesticated by the roaming curator class. We should not be cynical about this. This is how any institution works: through selection and power. This is not what made the SCCA network unique, we find that everywhere. What made it particular was its claim that this young generation of East-European artists looked at contemporary issues and modes of expression in a fresh way. This is a McLuhan-type statement, namely that those who are first to utilize a new medium are the ones who see most clearly the inner logic of the perception of that particular channel. This is why artists want to the be the first to utilize a new medium—and it is why we are annoyed by the clumsiness of the techno-imagination and the pop-style of advertisements. What East-Europeans were supposed to bring in was their humanist touch.

Hortensia Mi Kafchin, “Clay Water Soros” (2019). Image courtesy of Hortensia Mi Kafchin.

AM: Bulgarian artist Luchezar Boyadjiev once used the term “curated democracy” as a way of talking about the Open Call, the SCCA’s Annual Exhibitions and the conceptual qualities of cultural production back then. Other terms that resonated with me in thinking about this anomalous pattern were “pedagogical evangelism” and “scripted avant-garde.” I believe my research has confirmed this, but I also know that I was looking for it. Does this all seem like a convenient form of confirmation bias afforded to me by retrospective viewing?

GL: Wherever we went, contemporary art and the specific ways in which it was administrated turned out to be the institutional leftover of the historical avant-garde. Instead of the state-crushing art movements under communism, “civil society” transformed itself into a well-meaning supporter of artistic currents, albeit with clear political and pedagogic guidelines. We’re not talking here about independent art groups that rage against the machine. The idea was to connect Eastern Europe to the Western art market under the guidance of tastes and discourses that we set in New York.

AM: Could you describe those guidelines that were set in New York? And when you say “we,” do you mean that you as a SCCA director also helped to set these terms that would define cultural production? Is my speculation regarding coordinated implementation an art historical fantasy, a true conspiracy, or a really great coincidence?

GL: There was, for instance, the SCCAs’ great emphasis on “documentation” at a time when so much had already become “virtual,” fluid, and immaterial, including performances, installations, videos, net art, network activities, and socially engaged art with local people. These art practices only existed in the form of documentation. Those documents had to be collected somewhere, not just for grant purposes but also for the benefit of critics and visiting curators from abroad. This cultural ritual, what I call “playing office,” was then turned into an artwork itself. This is what I would also call a New York-style conceptual turn. The idea was to leapfrog an entire region “from zero to hero” in a few months. This is how fast it went. In particular, young artists who had already graduated from art school were very keen, immediately grasped the format, and participated in the annual SCCA survey shows and the documentation processes that were instrumental for the next stage, including applications to overseas biennales, residencies, and educational programs. The SCCA was a perfect machine.