The Intermedial Scattering of the Aura

Poetry & Performance: The Eastern European Perspective, Shedhalle, Zurich, August 16–October 28, 2018

The center of the spacious exhibition hall of Zurich’s Shedhalle was empty. Tomáš Glanc and Sabine Hänsgen, curators of the exhibition Poetry & Performance: The Eastern European Perspective,(Curated by Tomáš Glanc and Sabine Hänsgen, in corporation with Dubravka Djurić, Emese Kürti, Claus Löser, Pavel Novotný, Branka Stipančić, Darko Šimičić, Mara Traumane) purposefully arranged the exhibition’s artworks in a circular progression enclosing this empty center, and with the following sections: Writing-Reading-Performance; Audio Gestures; Interventions in Public Space; Body Poetry; Cinematographic Poetry; and Language Games. The device of the empty center facilitated the nonhierarchical and democratic character of the arrangement. The exhibition, which is currently touring parts of Central and Eastern Europe, presents more than 150 works by more than 50 artists from roughly a dozen countries, from the 1960s to today. Although during roughly half of this period the Soviet Union imposed political dominance over most of Eastern Europe, the artistic world explored in Poetry & Performance is diverse and knows of no center.

Shedhalle is a German word for a type of industrial building with a sawtooth roof that creates an especially bright influx of light without casting shadows. The “heavenly” atmosphere of the Shedhalle was bolstered by the predominantly white exhibition architecture of Prague architects RCNKSK. Works were hung on the walls of the hall, put in glass cabinets, shown on old-fashioned video screens, and in video booths. The booths had been constructed by covering welded cubic metal structures with paper. The works’ installation created open dialogues that due to the Eastern European artists’ embeddedness in the unofficial milieus of Socialism had never taken place in real life. As the curators argue, the parallel evolution of oftentimes similar artistic approaches and strategies not only took place “behind the Iron Curtain,” in relative separation from the West, but was also characterized “by barriers among those Eastern European cultures themselves.”(Tomáš Glanc, et al, Poetry & Performance. The Eastern European Perspective. Supplement to the exhibition, np.) Cleary, the appropriation of the artistic heritage of Eastern Europe by the global art market and Western institutions of knowledge production has been similarly unfit to create a unified cultural space, as these once peripheral cultures are now oriented towards this center, while the many ties between them are rarely activated.

Reading the exhibition title Poetry & Performance without further knowledge of its subject, one might think that it refers to the performance of poetry. The figure of the poet equipped with aura and authenticity was indeed common throughout the twentieth century, especially in Russia. This included, for example, Joseph Brodsky who embodied the spirituality of Russian literature in his American exile, or the bard Bulat Okudzhava who personified the post-Stalinist Soviet citizen’s newly acquired possibilities to express herself more freely. Glanc and Hänsgen tell the story of a different, complementary strain of avant-garde art: the intermedial existence of performance art as a unity of verbal utterance, subjectivity, and bodily presence.

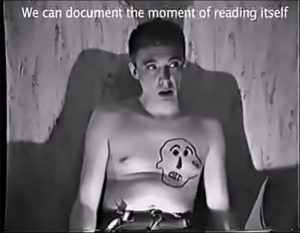

Andrei Monastyrski, “Conversation With the Lamp,” video still, 1985. Image courtesy of Hirt/Wonders.

Conversation with the Lamp by Andrei Monastyrski, on view in the opening section (Writing-Reading Performance), is central to the understanding of the exhibition. Monastyrski was one of the founding members of the Collective Actions Group, arguably the best known contemporary Russian art collective whose beginnings date back to 1976. Hänsgen, herself a long-time member of the group, filmed this performance with her Blaupunkt-VHS-Camera in 1985.(Günter Hirt and Sascha Wonders, Konzept – Moskau – 1985, Wuppertal: Edition S-Press. Digital Re-edition forthcoming (2019). ) The piece is, on the one hand, a positioning of Hänsgen herself as a “participatory observer,” and on the other, an example of how deeply poetry has transgressed into performance art. The setting of the film is rather intimate: young Monastyrski, naked from the waist up, sits in front of a wall onto which a lamp casts his shadow. He reads his free-verse poem “I hear sounds” (“Ya slyshu zvuki”) from a samizdat (underground publication).

The text read by Monastyrski recalls performances by important Russian poets of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, yet the focus continuously shifts away from the poets’ performance towards an incidental detail of the artistic space: the observer. This shift is being described by Monastyrski as an act of aggression towards these poets – and the “myth” around them – as well as being a conceptual starting point for the Collective Actions Group. Ironically the apparent destruction of the poet’s aura lies in its dislocation. Notwithstanding its silliness, Monastyrski’s speech is poetic: it demonstrates musicality and flow, and the diction is flawless. (Monastyrski is the most mythical and charismatic figure of Moscow Conceptualism.) The scattered aura of the poet is here consigned to the storage medium. As Walter Benjamin observed in “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” “cult value does not give way without resistance” and “the aura emanates from the early photographs in the fleeting expression of a human face.”(Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,”in Joanne Morra and Marquard Smith, eds.,Visual Culture, Vol. IV: Experiences in Visual Culture (London: Routledge 2006), p. 120. ) Similarly, in the film showing Monastyrski’s performance, cult value emanates from the pixelated black-and-white pictures of Hänsgen’s VHS recording.

Tamás Szentjóby, “Darkening Poem,” typescript, 1967. Courtesy of Tamás Szentjóby, acb Gallery, Budapest.

What became clear in the exhibition is that in the Socialist countries, the performativity of poetical practice emanated from unofficial culture. Unlike the West, the purpose was not to compete with consumer society and produce marketable works of art, but rather to subversively engage with the never-ending flow of socialist ideology. Two works gave testimony to this: a photograph documenting the installation of Slogan (1977), a red banner set in the middle of a remote winter landscape by the Collective Actions Group; and samples of appeals typewritten on small pieces of paper by Dmitri Prigov, one of the best-known Russian Conceptualist poets, who would deposit these pieces in public places in order to address his fellow citizens.

The restricted reproducibility of the works in the show, due to censorship and to the lack of technical innovation, endowed them with a special processual and performative character whose traces were visible in the exhibition. A notable example was a series of typewritten visual poems by Hungarian performance artist and poet Tamás Szentjóby where the letters on the page seemed to be set in motion, or the writing, placed below the paper’s edge, was forever in danger of becoming illegible.

“Audio Gestures,” the show’s second chapter, highlighted the transcendence of word-based poetry into sound or phonic poetry. In this intermedial practice, audio gestures can be captured in a visual poem that can then serve as a notation for the “invention” of sonic/phonic poetry. On view were pieces by Czech poets Josef Hiršal, Bohumila Grögerová, and Václav Havel, as well as West-German poet Gerhard Rühm who in 1969, during a “Semester of Experimental Creation,” created works at a radio studio in the remote North-Bohemian town of Liberec, just before the repressive order imposed after the Soviet invasion of Prague reached Czechoslovakia’s remoter parts.(The municipal museum of Liberec will be one of the next stops of the exhibition.)

As the exhibition demonstrated, sound poetry does not have to be limited to the reading of a poem. Katalin Ladik’s Phonopoetic (Phonopoetica) (1976), a breakthrough work in the field of sonic poetry, was an interpretation of the visual poetry of some of her fellow Hungarian poets. Typography in this instance served Ladik as a notation for musical intonation.(Emese Kürti, Screaming Hole: Poetry, Sound and Action as Intermedia Practice in the Work of Katalin Ladik (Budapest: acb Research 2017), p. 98. ) Musicality and, more concretely, notation also play a decisive role in Slovakian poet and artist Milan Adamčiak’s visual poetry, samples of which were presented at Shedhalle. In this intermedial practice, audio gestures can be captured as a visual poem that then can serve as a notation for the “invention” of sonic/phonic poetry. Visitors were able to listen to the works with headphones, while the video works were equipped with so-called “sound showers,” white pipes hanging from the ceiling under which the visitor could hear the respective soundtracks. This resulted in a veritable cacophony of voices and sounds that filled the space.

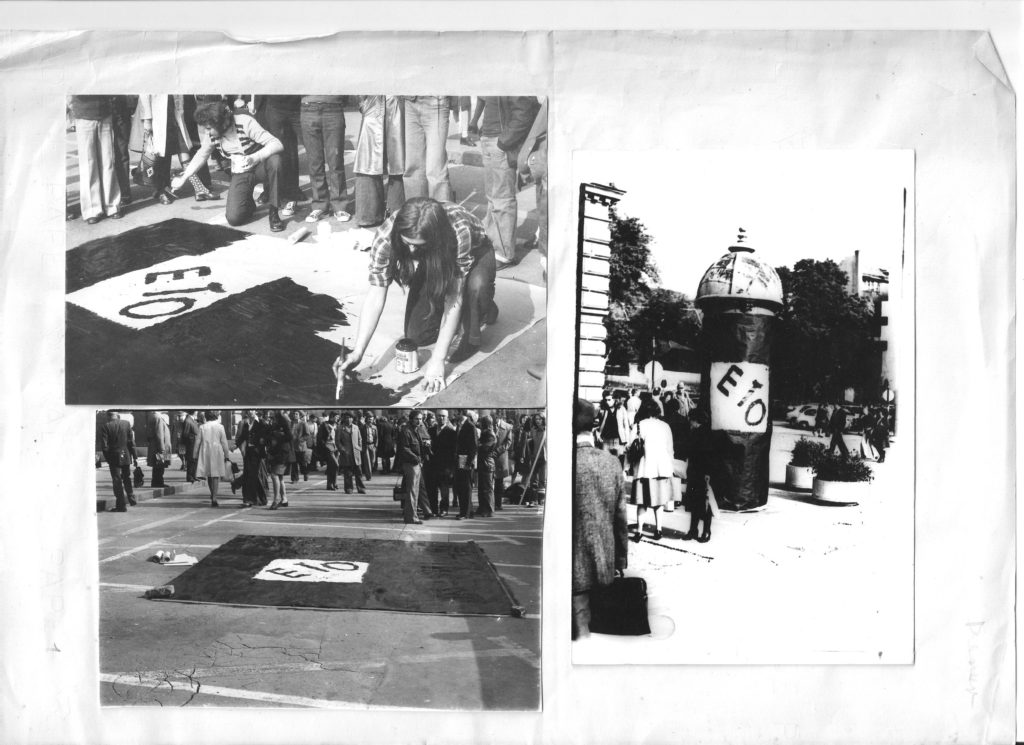

Boris Demur (exhibition action, Group of Six Artists), “Eto” (“Ecce”), black-and-white print, 1975. Image courtesy of Collection Darko Šimičić, Zagreb.

The first of several video booths served as a link between the sections “Writing-Reading-Performance” and “Interventions in Public Space.” Presented on the inside of one booth was a performance by Dmitry Prigov wearing a police hat on his head while reading poems in his role as a Soviet policeman (a militiaman, or, in Prigov’s colloquial rendering “militsaner”). In this famous reading-performance (published in 1985 alongside the above-mentioned work by Monastyrski), Prigov reads from his flat in the Moscow district of Belyaevo, on the periphery of the nation’s capital. Speaking in a not entirely ironic way, he creates the persona of the “poet-militiaman,” a mythical figure of higher moral authority safeguarding the “Muscovite cosmic order.” Shown on the outside of the booth was Pussy Riot’s action The Militiaman Enters the Game as performed during the finale of the 2018 Football World Cup in Moscow, documented here with an agency photograph and the group’s social media statement. The fact that this art-activist group would refer to such an example of subversive intelligentsia-tactics in a mass-media action, i.e. by deploying streakers in uniform, is quite curious. At any rate, the contrasting of these two very different documentary practices by means of a spatial metaphor was stark: inside, Hänsgen’s “insider-documentation,” originally distributed in a VHS edition and no longer available; on the outside, mass media sports coverage.

Tomislav Gotovac, “Degraffiting” 1990. Photo by Damir Alter. Image courtesy of Collection Sarah Gotovac, Tomislav Gotovac Institute, Zagreb.

Public actions from the 1970s by the Zagreb-based Group of Six Artists and the Voivodina-based group Bosch+Bosch, presented in the section Interventions in Public Space, bore witness to the fact that the freedom to perform publicly on the streets of Socialist Yugoslavia was unmatched in the rest of Eastern Europe. In Poland, for example, the Solidarity movement fostered experiments with language within the framework of activist and artistic happenings, as in Ewa Partum’s Hommage à Solidarność (1983) or Orange Alternative’s slogan “Away with the heat”(1987). In his photograph Degraffiting (1990), Croatian performance artist Tomislav Gotovac whitewashes a wall in the Croatian beach town of Fažana on the eve of Croatian Independance in 1989, as if to give “his fatherland” the possibility to begin a new chapter in national history. Needless to say, the palimpsest of graffiti is showing through the paint, and the job remains unfinished.

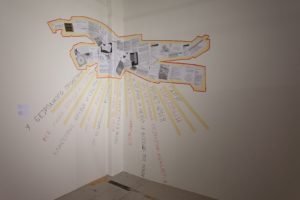

Today’s vivid Russian art and poetry scene is evidence to the fact that the digital world has become the new public sphere, while the streets and other physical spaces have become secondary venues for confronting the public, or merely rhetorica commonplaces. It is here that the poet-artist can engage in avant-garde “life-building.” It is also in the digital world that the artist and poet Roman Osminkin becomes the “flying proletarian” referred to in his mixed-media installation of the same title: a figure devoted to the “proletariat,” with equal parts moral fervor and self-ironic desperation.(See Mark Lipovetsky: “Mezhdu Prigovym i LEFom: performativnaia poetika Romana Osminkina”, in: NLO 2017/3.) The installation consists of his similarly-titled poem applied directly to the wall with a marker, together with the outline of a human figure giving the communist salute (reminiscent of superman in flight) and printouts of web pages.

Roman Osminkin, “The Flying Poetarian,” multi-media installation: mural painting, paper prints, sound, 2018. Photo by Jan Říčný. Image courtesy of Roman Osminkin, RCNKSK.

In contrast to the digital work above, the backward technical conditions in Eastern Europe under Socialism resulted in intense forms of poetry, as seen in the section Cinematographic Poetry. As the basic Super 8 cameras used by artists were unable to create a synchronized audio track, film material documenting performances of poetry is rather rare. Examples of Super 8 films from the former GDR (by Else Gabriel/Via Lewandowsky, Gino Hahnemann, Jörg Herold, Gabriele Stötzer) show how liberating the asynchronous use of words and pictures could be. Especially impressive was Hahnemann’s 1986 experimental film September September. Here, several verses on the nature of film are repeated several times in different expressive registers on top of a montage made up of found footage, East Berlin cityscapes, and “intertitles” (the film’s title is only given once in written form).

Katalin Ladik, “Poemim,” performance video, 10’42”, 1980. Video by Bogdanka Poznanović. Video still courtesy of Katalin Ladik, acb Gallery, Budapest.

While some of the works on view might be mere cursory ligaments of poetry and other media, Katalin Ladik’s oeuvre, occupying a major part of the “Body Poetry” section, clearly manifests a historical development. In her shamanistic performance UFO Party (1970), this artist from the Hungarian minority in Serbian Voivodina accompanied her poetic performance, half-naked, with a bagpipe and a drum. Along the way, Ladik’s Hungarian, in itself incomprehensible to the majority of her Yugoslav compatriots, dissolved into sonic poetry. As the photo series Experiment with Katalin Ladik (Attila Csernik, 1971) and Body Poetry (Csernik/Ladik, 1973) show, Ladik was willing to put her body as material at the disposal of male artists. Rather than Ladik’s overtly feminist performances deconstructing the male gaze (as seen in Black Shave Poem, 1978), it is the sheer virtuosity and power of the female artist that make her case for gender equality. (Dragomir Ugren, Miško Šuvaković: The Power of a Woman: Katalin Ladik: Retrospective, 1962-2010. Exhibition catalog, The Power of a Woman. Katalin Ladik. Retrospective, 1962-2010, The Museum of Contemporary Art Vojvodina in Novi Sad, November 26-December 15, 2010], Novi Sad: Muzej savremene umetnosti Vojvodine. ) In her video work Poemim, Ladik is shown in frontal view as she performs her sonic poetry, and then a series of manipulations of her face. Ladik’s control over her voice and body are truly impressive.

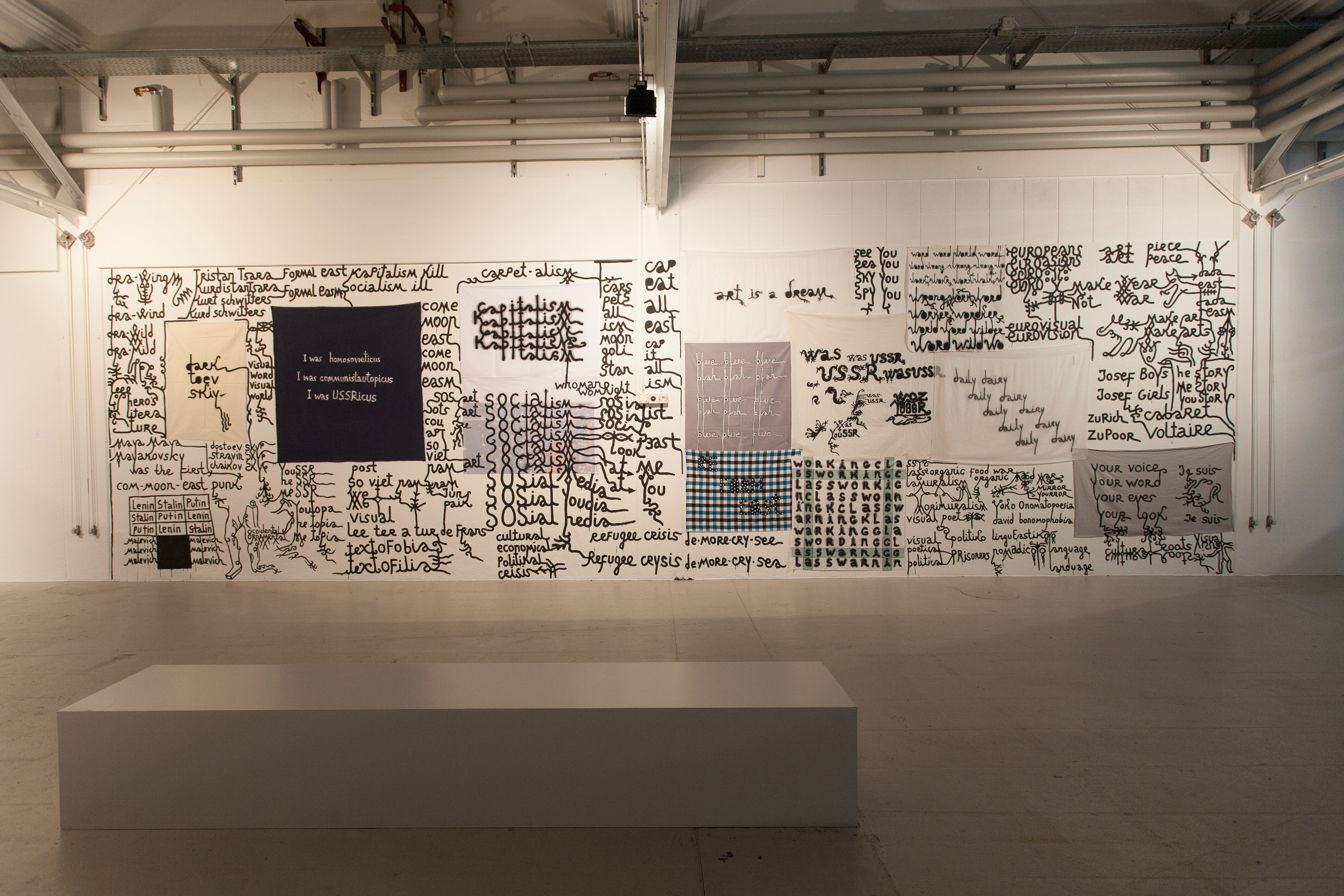

Babi Badalov, Installation view, mixed media: mural painting, cloth, 2018. Photo by Jan Říčný. Image courtesy of Babi Badalov, RCNKSK.

An almost monumental installation by the Azerbaijan-born, Paris-based artist and poet Babi Badalov was shown in the show’s last section, “Language Games.” Badalov sprays painted words onto a wall with an expressive gesture, oftentimes dissecting them into syllables and morphing them into other expressions and neologisms. This translation of glossolalia into writing created a typography that, from afar, reminded me of Koran surahs, an association sustained by the use of arrases (one reads, for example, “I was homosovieticus …”). Such works, indeed the last section as whole, prompted questions as to what the borders of Europe actually might be, given its own legacy of colonialism.

Poetry & Performance is a series of exhibitions, not a travelling exhibition. In each of its incarnations, the show adapts to local context.(In the case of Shedhalle, Egija Inzule, Julia Sippel, Daphni Antoniou.) While the thematic outline will remain the same, the changing composition of the works on display and the collaboration with local scholars and curators make Poetry & Performance a laboratory of continuous knowledge production.(To date, it was shown at the New Synagogue in Žilina (North Western Slovakia) December 23, 2017-March 10, 2018, and at Shedhalle in Zurich. The show opened at Dresden’s Motorenhalle on April 11, 2019.) One might argue that this research should be centered around questioning the essence of “performance” itself. While the exhibition’s reference to word-based poetry is substantial, it is at times perhaps not altogether clear what the curators mean by “performance.” One thing that does seem clear, also in view of the current show, is that the term cannot only be defined through its relation to a live audience (See Philip Ausländer: “The Performativity of Performance Documentation,” in A Journal of Performance and Art, Vol. 28, No. 3 (Sep., 2006), p. 6.), and that its authenticity and liveliness may be channeled by a documenting storage medium. The question is then how performance might be distinguished, more generally, from the inter-medial work of art.