Edi Hila: To Paint in the Eye of a Storm

Edi Hila: Painter of Transformation, Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw, March 2-May 6, 2018

Since its foundation in 2005, the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw has been engaged in an intellectually challenging attempt to reevaluate the artistic practice of several artists from post-war Eastern Europe whose works have so far mostly escaped under the radar of major Western art institutions. Shows by such artists as Andrzej Wróblewski, Ion Grigorescu, Alina Szapocznikow, Július Koller, Mária Bartuszová, among others, strived to move beyond the usual Cold War-era binaries of East and West, communism and capitalism, in order to show a more deeply complex and entangled reality. The exhibition of Albanian postwar painter Edi Hila continues this line of inquiry by putting forward the first comprehensive solo show of the artist’s works outside of his native country so far.

Hila’s artistic practice spans across several decades of Albania’s history starting from the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, to the transition period of the 1990s, and the years of stabilization in the 2000s. While he is regarded as a master figure in his country, his works have only recently gained recognition and visibility in the circuit of Western art institutions with the most decisive breakthrough coming in 2017 when a large selection of his paintings was included in Athens and Kassel as part of documenta 14. However, this rediscovery has yet to be followed by a more rigorous and focused historical research that highlights the idiosyncrasies of his practice. In fact, according to the curators of the show (Kathrin Rhomberg, Erzen Shkololli and Joanna Mytkowska), putting the exhibition together was a considerable challenge as Hila’s extensive artistic production, spanning more than four decades, has yet to receive in-depth critical attention from art scholars. This lack has prompted the curators to adopt a straightforward, chronological approach to the exhibition by dividing it into two blocks: one including Hila’s early works from the ‘70s, and the second, much more voluminous in terms of the number of pieces, focuses on paintings from the ‘90s and 2000s.

The first part of the show focuses on Hila’s early sketches and drawings from the 1970s and ‘80s after the artist graduated from the Academy of Fine Art in Tirana. Those decades were marked by a tightening of the political regime in the country. In 1958, Enver Hoxha broke off relations with Soviet Russia and formed a political alliance with Maoist China, which led to Albania’s total isolation both from Western and Eastern Europe. While such countries as Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia experienced in the second half of the 1950s a bigger degree of political and artistic freedom, Albania witnessed a new wave of repressions. Those factors resulted in an almost unprecedented artistifc isolation of the counfpoutry whose art education system for decades remained deeply rooted in nineteenth-century academic studio painting. In an interview Hila poignantly recalls how his main artistic inspirations in the ‘70s were coming almost entirely from Renaissance art albums smuggled from Italy.(Edi Hila, “We’re wasting a lot of time” interview with Angelika Stepken, Villa Romana, Florence 2007, https://www.villaromana.org/front_content.php?idcat=265&idart=333&lang=2 , access April 29, 2019.)

Edi Hila, “Planting of Trees,” 1972, oil on canvas. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw.

In 1972, the artist painted a large piece entitled Planting of Trees as a commission from the Albanian National Assembly that would prove to be decisive for both his later life and artistic career. The painting – dominated by vibrant greens and blues – represented a popular socialist motif of a group of young men and women planting new trees in an orchard. However, the work was denounced by the Albanian National Assembly in 1973 – the so-called Black Plenum because of its tragic outcome for Albanian artists and intellectuals – as degenerate art influenced by Western ideology. Hila claims that the accusation took him by surprise. However, if we compare the work to other pieces from the Albanian Socialist Realist canon we can better comprehend why it was deemed inappropriate by the party officials. While other official painters – such as Zef Shoshi or Spiro Kristo – represented workers frontally and statically to underline the importance of their historical role, Hila portrays the act of planting trees as an ecstatic dance, full of èlan vital, rather than a time of physical effort and labor. Indeed, the painting bears some resemblance to the Italian Renaissance painting the artist was getting acquainted with at the time. In a surprising historical twist, the Albanian revolutionary youth working in the orchard echoes the figures of nymphs and angels from Filippino Lippi’s wall frescos.

In the wake of the artistic and political scandal that surrounded the painting, Hila was convicted to a three-year-long “reeducation period” on a poultry farm. He was relatively lucky since other intellectuals, such as the writer Vilson Blloshmi, were sentenced to death. The verdict was a turning point for Hila who had to leave Tirana and move with his family to a mostly agricultural – and even more isolated – area in the south of the country. His practice was deeply affected by this change: starting from 1974, he largely stopped painting and turned instead to drawing and sketching smaller works. One of the artist’s most remarkable works from the second half of the ‘70s is the series Poultry (1975-1976), painted with pencil, tempera and black ink. The drawings can perhaps be best described as an artistic social reportage that engages with the life and working conditions at the poultry farm to which the artist was relegated. In this period, Hila appears to turn his back on his earlier style, establishing instead the foundations for a new artistic sensibility and method.

Edi Hila, “Women Workers” from the series “Poultry,” 1975, ink on paper. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw.

In the Poultry series, the painter’s main focus is on the farm’s workers, usually portrayed in larger groups while they carry out their chores, eat at the canteen or take a break, lying starched on piles of sacks. In contrast to Socialist Realism, which tended to portray the labor of the working class in terms of a heroic struggle, Hila does not romanticize his subjects: age, fatigue, harsh working and living conditions have all imprinted their marks on the workers’ bodies. The series also reflects the artist’s exceptional observation skills that allow him to capture an extensive array of subtle gestures, facial expressions, and idiomatic behavior. According to the artist, his main point of reference for these drawings were Gustav Courbet’s paintings portraying the life of French peasantry in the nineteenth century. Hila’s choice to engage with Courbet’s works can be seen as an attempt to recuperate the artistic and social potential of Realism in opposition to the already ossified canon of Socialist Realism in Albania. However, it should be remarked that the artist never considered his works “dissident art” – a label that Western art institutions are all too ready to apply to artists from (former) totalitarian countries.

Edi Hila, “Fight” from the series “Poultry,” 1975, acrylic on canvas. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw.

Surprisingly, in some of Hila’s works from the ‘70s we encounter an unexpected comical and satirical flair which seems to undermine both the direness of the artist’s individual situation and that of communist Albania at large. The oil painting Fight from 1975 portrays a brawl among two workers. However, in a surprising twist, the riot has an almost choreographic quality to it that is further emphasized by the use of white and blue hues. The two men seem to hover above the ground locked it what looks like an embrace rather than a fight. Furthermore, their pale faces – distorted by wide grins – echo the visual language of the Italian commedia dell’ arte. A similar satirical trait appears in the portrait Snitch from the Security Service from 1974. The man in the painting, dressed in a vivid yellow shirt, with a briefcase and an umbrella under his arm, seems to have directly stepped out of Nikolai Gogol’s satirical plays. His flushed cheeks, wide grin and a tie that comically blows in the wind all point out to a comical character. Meanwhile the man in the painting bears close resemblance to other Gogol characters: corrupt officials, shrewd apparatchiks and members of the local petit bourgeoise. As in the case of Fight, Hila portrays a potentially threatening situation in a lighthearted way further emphasized by the use of bright, brilliant colors. This comical flair is undoubtedly linked to the emergence of a specific form of satire and humorous ridicule in all countries of Eastern Europe and Soviet Russia under the authoritarian regimes.

The second part of the exhibition focuses on Hila’s more recent works from the ‘90s and 2000s, marked by the artist’s return to large format oil paintings. While many Albanian artists swiftly abandoned Socialist Realism after the collapse of the regime in 1991, Hila continued his engagement with figurative painting. However, in a certain way his works underwent profound changes. Starting from the early ‘90s a cool, analytical – indeed almost detached – approach starts to dominate the artist’s practice. His main subject shifts to architectural spaces and buildings, with the human figures often fading into the background. The painter takes on the role of an attentive yet estranged observer who dispassionately keeps a record of the ongoing changes in the country. His color palette echoes those changes: starting from the early ‘90s he makes frequent use of washed-out grays and sepias, ashy blues, and yellows. These muted colors further deepen a sense of detachment as if the things Hila portrays were happening behind thick glass or on the screen of an old TV model.

In December 1990, Albania witnessed the collapse of the one-party system, followed by the toppling of Ramiza Alii’s pro-communist government. The next decade – in stark contrast to the expectations of Albanian people – didn’t bring an improvement of living conditions but quite the opposite. In 1997, unrest broke out in the country sparked by a crash of the financial system: demonstrations took place in all of Albania, often resulting in riots and violent clashes. During the six-month period of unrest there were more than 2,000 people killed. Ultimately, order had to be restored by a military intervention by the United Nations. All those events created a sense of profound disillusionment within Albanian society regarding the new neoliberal order and its leaders. The violence of the Albanian Civil War has led scholars and commentators to question the term “transformation in relation to the democratic changes in the country. Indeed, rather than a transformation, it was a violent rapture. As such, a question can be raised about the curators’ choice to entitle Hila’s show Painter of Transformation in order to underline the supposed similarities between Poland and Albania’s historical developments. In fact, what emerges from the exhibition and a more careful reading of Hila’s practice is the fundamental incomparability of the two realities that all too often get conflated in Western (and, apparently, Eastern) discourses.

Hila’s artistic practice was also deeply affected by the increasing presence of new media in Albania and Eastern Europe after 1990. Especially photography plays a key role in his more recent works. Hila often uses photos as his starting point, which he then “translates” into the language of painting. This artistic strategy places him in close relationship to other artists from the ‘90s who employed a similar strategy, such as Luc Tuymans or Wilhelm Sasnal. The parallel with Tuymans seems particularly apt as both artists use photography as a “distancing device” that allows them to take a step back from reality, while nevertheless maintaining a mimetic relationship to their subjects. This separation is necessary in order to develop an analytic coherence of vision in contrast to the constant overproduction of new images. Interestingly, this notion of necessary distance closely echoes Charles Baudelaire’s remarks in “The Painter of Modern Life” where he declares his skepticism as to whether photography is truly able to capture the spirit of modernity. It was rather painting – the author famously claimed – that possessed the necessary autonomy to offer judgments, a claim fully shared by Hila.

Edi Hila, “Street Scene” from the series “Paradoxes,” 2005, oil on canvas. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw.

According to Albanian curator Edi Muka, Hila reached his full artistic maturity around the 2000s. The Warsaw exhibition focuses extensively on this last decade, featuring, among others, the series Threat (2003-2009), Relations (2002-2014), Margins, (2010-2011) and Roadside Objects (2007-2010). Most of these series have Tirana as their subject, often portrayed as a place of perpetual tension and underlying threat, full of ambiguous or straightforwardly endangering situations. The painting Anticipation (2009), for instance, features a group of men waiting outside a low building, perhaps a train or bus station. We can’t be certain what they are doing there, but their body language – arms crossed, legs firmly planted on the ground, bodies slightly tilted forward – seems to imply potential aggression or violence. Similarly, in Street Scene (2005) several passersby surround a figure lying flat on the pavement. However, it remains unclear whether they mean to help the figure or if they prefer to only to passively observe. Interestingly, both paintings clearly show the Albanian painter’s longstanding fascination with Italian pittura metafisica. Indeed, Hila’s Tirana at moments echoes De Chirico’s paintings of classical piazzas populated with spectral figures and shadows. However, while De Chirico’s aesthetic was strongly rooted in Surrealism and psychoanalysis, Hila’s view of Tirana stems from a collective traumatic experience of history as experienced by Albanians over the last sixty years.

Color plays a central role in Hila’s mature artistic practice. His paintings from the last two decades are dominated by muted and cold hues: washed-out grays, lusterless blues, whites, and yellows. Starting from the ‘90s, his works are almost entirely devoid of brilliant colors – usually associated with the southern landscape – as if everything was covered by a thick layer of dust or sand. Hila paints with light, narrow strokes which further reinforces the effect of brittleness. As in Tuymans case, this radical reduction of color deepens the sense of separation and distance. This is also the case with Hila’s more recent Boulevard series (2015), featuring Tirana’s principal street: over the decades the boulevard has witnessed several successive authoritarian governments, from the monarchy and the Italian occupiers to the communists. Apart from their marked political and historical connotations, these paintings stand apart for their specific color scheme. Hila portrays the avenue and its concrete buildings using a narrow spectrum of dark grays and listless blue tones. Some parts of the paintings seem to verge almost on the monochromatic. Seamlessly, figuration morphs into abstraction. The presence of those flat surfaces infused with color confers on the works a specific quality that at times echoes the style of color field painting.

Edi Hila, “Street Scene” from the series “Paradoxes,” 2005, oil on canvas. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw.

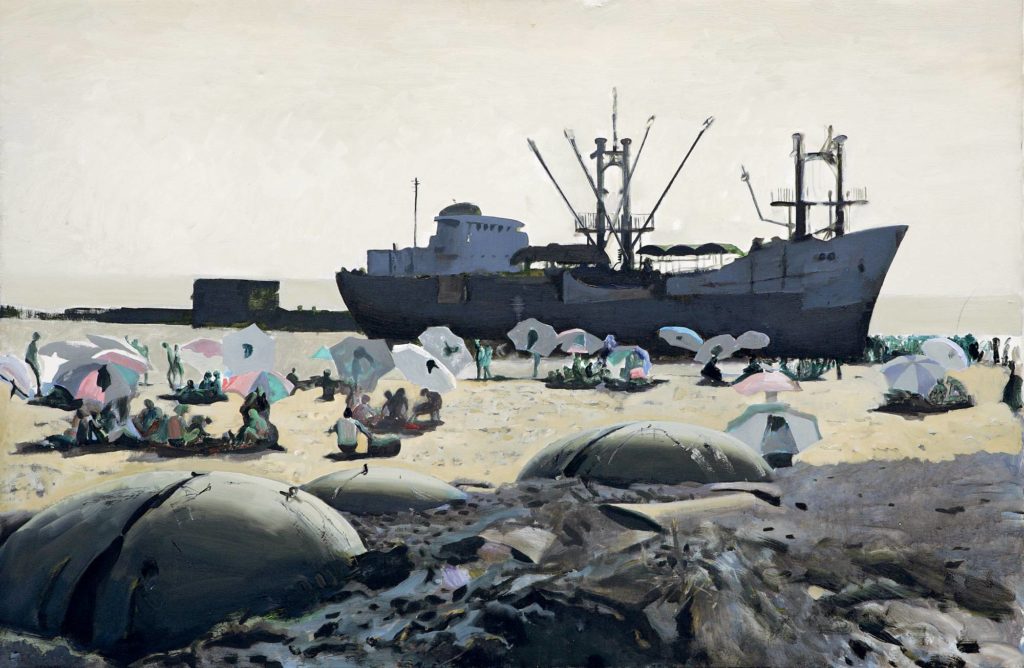

There can be little doubt that Hila takes a very critical stand towards the “transformation” process in Albania after 1990. However, some recent works also offer a more optimistic vision that echoes the vitalistic and comic flair of his earlier practice from the ‘70s and ‘80s. In the series Roadsides Objects (2007-2010) Hila records the things people put out on sale outside their houses, among them a wedding dress and an aquarium. Those paintings stand as testimonies to people’s resourcefulness, determination, and survival skills that allow them to come up with unexpected ideas and solutions. A similar case can be argued for the painting Under the Hot Sun (2005) that shows a beach with an old cargo vessel moored in the background. Among the dunes, there are several bomb shelters – a reminder that during Hoxha’s regime in Albania, more than 200 concrete bunkers were constructed. However, Hila’s main focus is not on those historical elements but rather on the people sitting under umbrellas or walking alongside the sea. The piece demonstrates that the painter’s primary concern is not history as such, but how people inhabit historical circumstances by making even the harshest conditions their own. In this sense, Hila’s artistic practice signals a deep belief in people’s tenacity and resilience even when confronted with decades of political oppression, poverty, and violence.

Edi Hila, “Under the Hot Sun” from the series “Paradoxes,” 2005, oil on canvas. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw.

The exhibition Painter of Transformation marks another step in the resurgent interest in Edi Hila. It can’t be stressed enough that this new visibility needs to go hand in hand with much needed academic research concerning his artistic practice both before and after 1990. Only a careful reconstruction of the historic and artistic context within which he operated can help to avoid curatorial and art historical clichés that often place artists from Eastern Europe under the usual labels of “dissident art” or “post-communist nostalgia.” This is especially true in the case of Albania whose historical and artistic development is in sharp contrast to those of other countries in the region. Furthermore, while some critical attention has been devoted to artists from Albania who emerged in the ‘90s, including Anri Sala, Adrian Paci and Edi Rama, little has been written in English about the older generation. Hila himself seems to be aware of this danger, claiming in an interview that “he wants to talk about his art, not the regime.” (Edi Hila, „I want to about my art, not the regime” in: Kosovo 2.0 Online magazine, https://kosovotwopointzero.com/en/edi-hila-want-talk-art-not-regime/, access April 29, 2019.)