Art in Europe 1945-1968: Facing the Future

Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe, October 22, 2016—January 29, 2017

On January 29, 2017, the Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe celebrated the successful conclusion of Art in Europe 1945-1968: Facing the Future, a major exhibition dedicated to European art after the Second World War. Showcasing some 500 artworks by more than 200 artists, the exhibition was the collaborative effort of the Center for Fine Arts in Brussels (BOZAR), the Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe (ZKM), and the Moscow State Museum Exhibition Center (ROSIZO), and Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts. After stints in Brussels and Karlsruhe, the exhibition opened at Moscow’s Pushkin Museum on March 7, where it will run until May 21.(The exhibition was on view in Brussels June 24 – September 25, 2016, and in Karlsruhe October 22, 2016 – January 29, 2017.)

The exhibition traces the development of artistic neo-avant-gardes across the European continent from the end of the Second World War in 1945 until 1968—the year of student protests and the Prague Spring. In doing so, Art in Europe 1945-1968 offers a new perspective on the art of this period, challenging the usual East-West dichotomy to reveal commonalities and affinities within European artistic space that cut across political and ideological divides. In seeking to surpass the familiar art historical narrative of a continent split between Abstract Expressionism as a symbol of Western freedom, on the one hand, and Socialist Realism as marker of the authoritarian communist East on the other (a division that was itself a product of the Cold War discourse), curators Eckhart Gillen and Peter Weibel bring together an impressive and diverse selection of works to demonstrate that many of the art forms that emerged after WWII, from Pop Art to Conceptual Art, were common to Western Europe, the United States, the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. The rationale and urgency underpinning this effort to highlight the pan-European quality of post-War art is articulated as “an active plea for Europe,”(Peter Weibel, “Introduction,” in Art in Europe 1945-1968, The Continent that the EU Does Not Know, Supplement to the exhibition catalogue (ZKM Karlsruhe, 2016), 6.) with the exhibition registering its “opposition to the current economic and political tales that drive Europe apart,” and pointing instead to the continent’s shared artistic heritage as a force of unity.(Weibel, “Introduction,” 6.)

Organized around a chronological structure and divided into ten sections, the show outlines the formal evolution of visual arts after the War. After opening with various forms of figurative art depicting the scale of Europe’s post-War devastation, focus shifts to the subsequent break with representation and move towards abstraction, exemplified by the non-geometric abstraction of Art Informel and Tachisme, and also by works revisiting experiments in geometric abstraction by historical avant-gardes. The introduction of real objects into art as a substitute for representation is then explored, across a survey of phenomena including Nouveau Réalisme, Arte Povera, Pop Art and forms of Soviet and Eastern European non-conformist art. The exhibition also covers the incorporation of new technology into artmaking with Kinetic, Op and Cybernetic Art, before turning to the birth of Activist Art, the rise of Conceptual Art, and ultimately the emergence of Media Art. Importantly, these formal developments are framed by the curators in terms of the psychological processing of the trauma of the Second World War: from a state of crisis brought on by an inability to respond to the barbarism of war, art would gradually overcome this impasse by embracing new forms of expression. This framework underscores the exhibition’s argument for a pan-European reading of the art of this period, for trauma does not recognize an East-West divide, but functions instead as common ground for (and an explanation for the parallels within) artistic research that was to follow across Europe.

Organized around a chronological structure and divided into ten sections, the show outlines the formal evolution of visual arts after the War. After opening with various forms of figurative art depicting the scale of Europe’s post-War devastation, focus shifts to the subsequent break with representation and move towards abstraction, exemplified by the non-geometric abstraction of Art Informel and Tachisme, and also by works revisiting experiments in geometric abstraction by historical avant-gardes. The introduction of real objects into art as a substitute for representation is then explored, across a survey of phenomena including Nouveau Réalisme, Arte Povera, Pop Art and forms of Soviet and Eastern European non-conformist art. The exhibition also covers the incorporation of new technology into artmaking with Kinetic, Op and Cybernetic Art, before turning to the birth of Activist Art, the rise of Conceptual Art, and ultimately the emergence of Media Art. Importantly, these formal developments are framed by the curators in terms of the psychological processing of the trauma of the Second World War: from a state of crisis brought on by an inability to respond to the barbarism of war, art would gradually overcome this impasse by embracing new forms of expression. This framework underscores the exhibition’s argument for a pan-European reading of the art of this period, for trauma does not recognize an East-West divide, but functions instead as common ground for (and an explanation for the parallels within) artistic research that was to follow across Europe.

A section entitled Trauma and Remembrance serves as a powerful opening gambit, bringing together images of devastation and mourning from a series of watercolors of Berlin in 1945 by Alexander Deineka—composed as the artist entered the city with Soviet troops—to Hans Richter’s imposing Stalingrad, Victory in the East (1943-1944), a five-meter long collage of newspaper clippings reporting on the decisive Soviet victory over the Germans. Dominating this section are works that contemplate human sacrifice, most powerfully expressed in a paring of Pablo Picasso’s studies for Man with Lamb (1942), with its Christian symbolism of the sacrificial lamb on the one hand, and Vladimir Tatlin’s little known canvases Meat (1947), and Skull on the Open Book (1948-1953), both evoking the quiet still lives of Dutch masters and their memento mori theme, on the other. Here, two titans of European avant-garde, artists who obliterated all traditional notions of art during the 1910s and 1920s, seek recourse in European classical heritage as a way of reckoning with contemporary horrors. Stylistically diverse, these works succeed in portraying a tension brought on by the realisation that existing visual language struggled to depict a wartime experience of such unparalleled and perverse magnitude.

Faced with a crisis of representation (and, by extension, a crisis within easel painting), artists turned to abstraction. This move would encompass a wide range of responses, including works such as Fire (1948) by Polish artist Jerzy Nowosielski, in which a set of geometric shapes and lines floats against a white background reminiscent of the abstract art of historical avant-gardes. Elsewhere, the effort to dismantle representation went beyond the focus on painterly means of representation—point, line, surface and colour—and sought in fact to physically destroy them. Here, the image retreats as the canvas becomes a battlefield: Yves Klein sets it ablaze in his fire paintings (1962), while Lucio Fontana rips it apart in Space Concept (1963), as the experience of violence and destruction of meaning is reenacted.

Faced with a crisis of representation (and, by extension, a crisis within easel painting), artists turned to abstraction. This move would encompass a wide range of responses, including works such as Fire (1948) by Polish artist Jerzy Nowosielski, in which a set of geometric shapes and lines floats against a white background reminiscent of the abstract art of historical avant-gardes. Elsewhere, the effort to dismantle representation went beyond the focus on painterly means of representation—point, line, surface and colour—and sought in fact to physically destroy them. Here, the image retreats as the canvas becomes a battlefield: Yves Klein sets it ablaze in his fire paintings (1962), while Lucio Fontana rips it apart in Space Concept (1963), as the experience of violence and destruction of meaning is reenacted.

If abstraction was one way to deal with this crisis in representational art, another response—in a gesture reaching back to Marcel Duchamp’s readymades of the 1910s—was to substitute depictions with the real thing. In investigating this penetration by everyday objects and mass culture into the realm of art, a series of exhibition spaces demonstrate that this trend in post-War art, despite so often being exclusively associated with the appearance of Pop Art in Great Britain and the United States, was in fact a common European phenomenon. This shared “Pop sensibility”(Alexandra Danilova, “In the Gap between Art and Life, Pop Sensibility in European Art 1950-1960s,” in Art in Europe 1945-1968: Facing the Future (Tielt: Lannoo Publishers, 2016), 288.) would manifest itself in various ways across the continent (such as the Nouveau Réalisme and Arte Povera movements), with artists seeing in real objects both an opportunity to move away from abstraction, and also to comment on the terrors of the market economy and the emerging culture of waste.  Daniel Spoerri’s The Blue Table: Restaurant of Galerie J. (1963), consisting of a table mounted vertically against a wall—complete with plates containing remains of a meal—serves as a classic example of this trend in Europe. Importantly, this approach was also present across Eastern Europe and in the Soviet Union, where artists belonging to the unofficial or non-conformist scene similarly experimented with real objects and popular iconography in their artmaking to comment on the ruthless mass production not of consumer goods, but of Soviet ideology—as well as the dullness of socialist daily life. The presence of, for example, Oskar Rabin’s Russian Pop-Art No. 3 (1964), in which Andy Warhol’s Campbell Soup cans and Coca-Cola bottles are replaced with a bottle of vodka and a dried fish, and Mikhail Roginsky’s Matches (1960) and Wall with Socket (1965), which both zero in on the banal, support the exhibition’s argument of shared artistic sensibility more convincingly than the preceding section on abstraction.

Daniel Spoerri’s The Blue Table: Restaurant of Galerie J. (1963), consisting of a table mounted vertically against a wall—complete with plates containing remains of a meal—serves as a classic example of this trend in Europe. Importantly, this approach was also present across Eastern Europe and in the Soviet Union, where artists belonging to the unofficial or non-conformist scene similarly experimented with real objects and popular iconography in their artmaking to comment on the ruthless mass production not of consumer goods, but of Soviet ideology—as well as the dullness of socialist daily life. The presence of, for example, Oskar Rabin’s Russian Pop-Art No. 3 (1964), in which Andy Warhol’s Campbell Soup cans and Coca-Cola bottles are replaced with a bottle of vodka and a dried fish, and Mikhail Roginsky’s Matches (1960) and Wall with Socket (1965), which both zero in on the banal, support the exhibition’s argument of shared artistic sensibility more convincingly than the preceding section on abstraction.

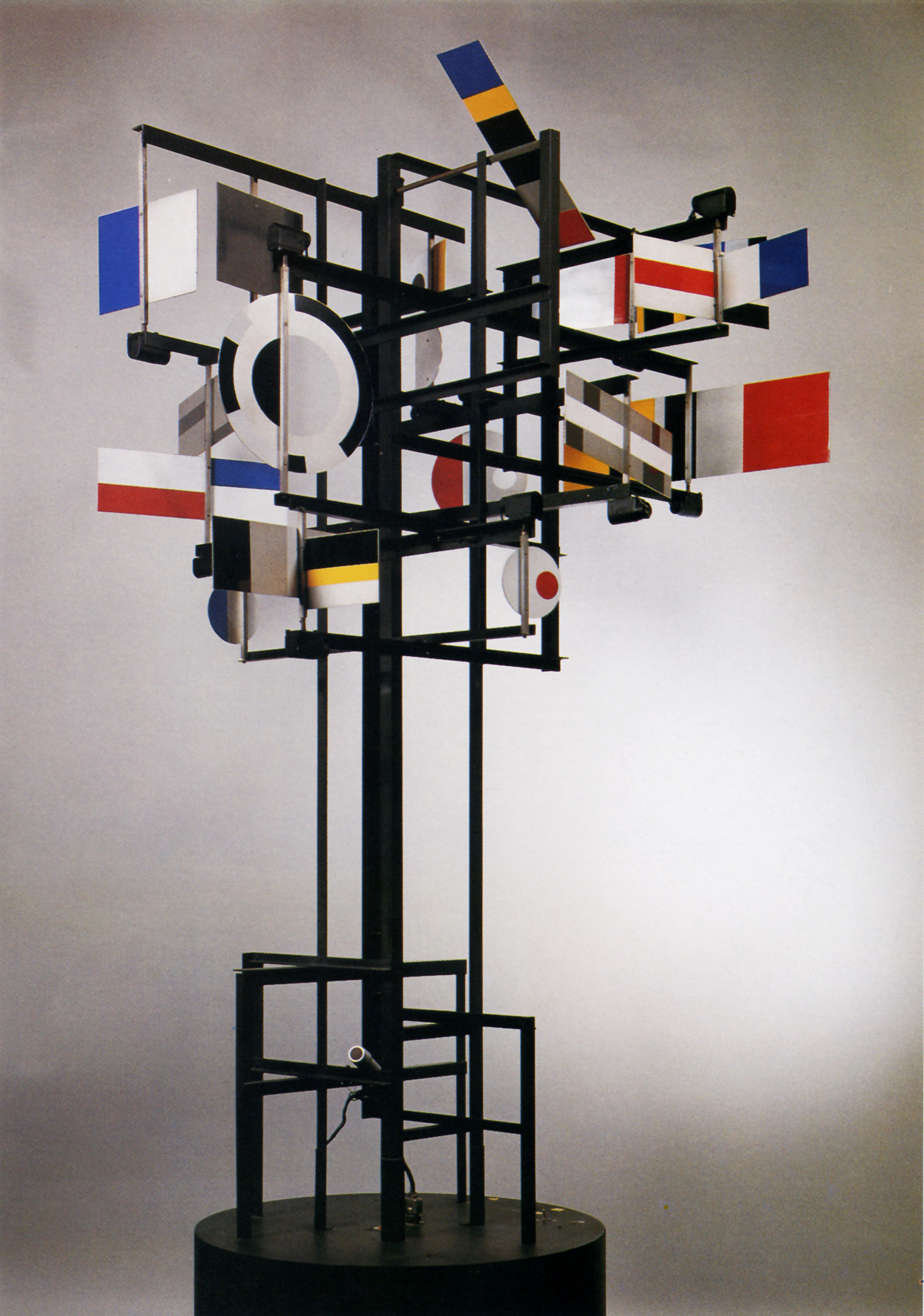

This engagement with real objects and everyday life paved the way for the discovery of new methods, new materials, and new media—and thereby fuelled a range of, as the title of the subsequent section has it, “New Tendencies” in art. In focussing on how science and technology—and a widespread fascination with space exploration—served as an important impetus for artistic research across Europe, this section begins by paying tribute to a series of exhibitions (also entitled New Tendencies) that began in Zagreb in 1961, and from which this new art began reaching larger audiences. A range of Op Art and Kinetic Art pieces, in which color, light and motion combine into dizzying visual effects is followed by a section dedicated to Cybernetic Art, a movement which saw computer technology emerge as both a tool and medium for art. Among the works on display, a photograph of the first cybernetic sculpture CYSP 1 (1956) by the father of Cybernetic Art, Hungarian-born French artist Nicolas Schöffer is a highlight: in this photograph we see the first artwork with an “electronic brain”—a sculpture that moved around on rollers, responding autonomously to changes in ambient light and sound.

The exhibited examples of Op, Kinetic and Cybernetic Art, which are today for viewing only but with which earlier audiences would have once engaged directly by touching, altering, moving or setting in motion to produce an associated effect, are presented as a step towards a more participatory art. This exploration of participatory artistic trends culminates in a section that considers the phenomenon of Action Art. Selected pieces explore the shift in focus from artwork to artist, such as in Joseph Beuys’s The Chief (1964), in which the artist—laying on the floor, wrapped in a felt blanket, and surrounded by the audience—made the growling sounds of a wounded animal for hours on end, recalling his pain after his plane had crash-landed during the War. Other works explore a new approach to the exchange between audience and artist, such as Actual Walk along Novy Sv?t – Demonstration for All Senses (1964) and Demonstration of the One (1964) by Milan Knížák, who would produce bizarre scenes in the streets of Prague to distract passers-by from their daily routines. Fuelled by student unrest and discontent with the dominant political and economic systems, artists across Europe engaged in Action Art to explore the tense relationship between art production and political action, and the possibility of transforming everyday life.

The exhibited examples of Op, Kinetic and Cybernetic Art, which are today for viewing only but with which earlier audiences would have once engaged directly by touching, altering, moving or setting in motion to produce an associated effect, are presented as a step towards a more participatory art. This exploration of participatory artistic trends culminates in a section that considers the phenomenon of Action Art. Selected pieces explore the shift in focus from artwork to artist, such as in Joseph Beuys’s The Chief (1964), in which the artist—laying on the floor, wrapped in a felt blanket, and surrounded by the audience—made the growling sounds of a wounded animal for hours on end, recalling his pain after his plane had crash-landed during the War. Other works explore a new approach to the exchange between audience and artist, such as Actual Walk along Novy Sv?t – Demonstration for All Senses (1964) and Demonstration of the One (1964) by Milan Knížák, who would produce bizarre scenes in the streets of Prague to distract passers-by from their daily routines. Fuelled by student unrest and discontent with the dominant political and economic systems, artists across Europe engaged in Action Art to explore the tense relationship between art production and political action, and the possibility of transforming everyday life.

As Art in Europe 1945-1968 builds towards its conclusion, focus shifts from the performative turn in Action Art to the linguistic experiments of Conceptual Art, for which language became a critical medium. These final sections demonstrate the diversity of Conceptual Art. For example, works by British group Art & Language, in which the words “Painting” and “Sculpture,” written on two panels (in Painting Sculpture, 1968), are placed alongside Automatic and Chickens (1966) by Ilya Kabakov—one of the leading figures of Moscow Conceptualism—in which a Kalashnikov rifle is drawn in a naïve, childlike style above a pair of egg-shaped recesses containing baby chickens. Functioning as a throwback to the visual jokes and puns of Russian Futurism during the 1910s, Kabakov provides a commentary on Soviet underground artists preferring to fade into the background or remain down in a hole to avoid being shot at.

The embrace of new technologies and new media ultimately sees the canvas and indeed the image itself gradually give way to new methods and materials, culminating in the rise of Media Art. In its entirety, Art in Europe 1945-1968 traces the formal evolution of post-War neo-avant-gardes and, as this narrative unfolds, the exhibition insists that its story of artistic evolution demonstrates a psychological and creative approach to working through a shared trauma, rather than merely a return to strategies of historical avant-gardes. This approach is not without its problems: the ten section model used to present this story is sometimes difficult to follow, as categories that focus on formal aspects (like Abstraction or Action Art) are often mixed problematically with those that are more thematic (such as Trauma and Remembrance). Furthermore, the extent to which the exhibition successfully challenges the East-West divide in post-War Europeanart is questionable, especially as the historical context of art from the East is played down in favor of formal similarity with Western art. In addition, a large number of works from Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union are by artists associated with the unofficial (non-conformist) art scene, which hardly captures the full complexity of artistic development in these nations. Ultimately the exhibition leaves itself open to criticism that its structural categories were determined from a Western perspective, augmented with selected works from the East that fit the bill.

The curators, however, are upfront in acknowledging that their categorisation of selected works cannot capture the full diversity and complexity of the artistic landscape in this moment. Yet despite this challenge, Art in Europe 1945-1968 succeeds in highlighting a number of common post-war artistic tendencies across the continent. The Karlsruhe exhibition—which is the largest in the series—achieves this by bringing together such a vast array of pieces, and thereby providing the unique opportunity to see works by the likes of Oskar Rabin or Mikhail Rabinsky as part of a larger European story of Pop Art, or the role of the Yugoslav art scene in the evolution of Cybernetic Art. By demonstrating how commonalities in art across Europe evolved in response to shared trauma, the exhibition as a whole delivers a powerful message: against narratives that foreground divisions, it offers an alternative story of Europe as a common intellectual and cultural space. It is this principle of universality that, with our differences and intolerances fully acknowledged, has united Europe in an emancipatory struggle for some seven decades(Slavoj Žižek, “What Does Europe Want?” Art in Europe 1945-1968: Facing the Future, 487-493.) —an achievement that we must remember, and continue to pursue.