Hommage à Malevich: Black Square Continued

HOMMAGE À MALEVICH: BLACK SQUARE CONTINUED, MESTNA GALERIA LJUBLJANA, JULY 2 – SEPTEMBER 6, 2015

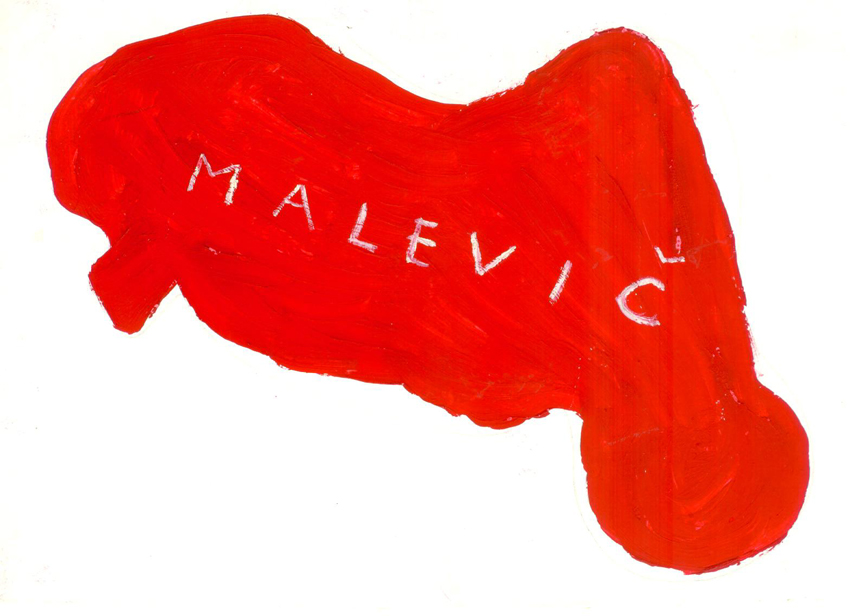

Curated by Mateja Podlesnik at Ljubljana’s City Art Gallery to mark the centenary of Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square (1915), Hommage à Malevich: Black Square Continued tracks artistic references to Suprematism from late-socialist Yugoslavia and its later independent former republics. The significance of this shared reference is found in two works by Vlado Martek, a Croatian poet and artist, that hang roughly at the midpoint of the exhibition’s first floor. Started in the same year that an anthology of the Suprematist’s writings appeared in translation,(Kazimir Severinovich Malevich and Slobodan Mijuskovi?, Kazimir Maljevi?: suprematizam, bespredmetnost: tekstovi, dokumenti, tuma?enja [Kazimir Malevich: Suprematism, Non-Objectivity: Texts, Documents, Interpretations (Belgrade, Student Publishing Center, 1980).) the series Artists, Read Malevich (1980–2002) is here represented by six framed pieces of paper on which Martek wrote that injunction in different languages. On an adjacent wall, Yugoslavia – Malevich (1984), a tiny tempera on cardboard, adds the Russian artist’s last name to a lumpy red representation of the country (fig. 1). As the protected color of communism, red could not be appropriated at will; Martek’s reclaiming of it for an alternative vision to the socialist modernism promoted by the state hints at how post-conceptual artists working across these territories in the early 1980s were in a better position to “read Malevich” than their American counterparts, who were largely drawn to the combination of reductive formalism and vague revolutionary potential.(For more details on Malevich’s American reception, see Alison McDonald and Ealan Wingate, eds, Malevich and the American Legacy, exh. cat. (New York: Gagosian Gallery, 2011).)

In this sense, Hommage à Malevich is the ideal complement to Zdenka Badovinac’s ambitious retrospective of the Neue Slowenische Kunst (NSK) running almost concurrently at Ljubljana’s Museum of Modern Art. With few exceptions, the selected works (by Martek, Goran Djordjević, Bojan Gorenec, (the Belgrade) Kazimir Malevich, Dragoljub Raša Todosijevi?, Mladen Stilinovi?, Radenko Milak, IRWIN, Dimitry Orlac, Ištvan Išt Huzjan, Tanja Ostoji?, Igor Grubić, Duša Jesih, and Vladimir Nikoli?) show how the memory of Suprematism helped these artists develop common critical strategies that challenged ideological systems, from the state’s repressive structures to inherited artistic traditions from the East and West alike.

First shown in 1915 at The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0.10 in a private Petrograd gallery, Black Square reappears in multiple guises here. For Malevich, the painting stood for the ideal of zero form yet was never associated with entropy, becoming instead a limitless space where all readymade structures were cleared away. Along with the circle, cross, and other non-objective motifs, the square provided Djordjević witha recognizable modernist unit that was easy to copy and make a key element in a story about the copy. Indeed, any account of Yugoslav appropriation begins with the former Belgrade artist, who is here represented by six projects including “K.M.” Copies (1980), a salon-style hanging of ten deliberately amateurish copies painted off-center on larger pieces of hardboard (fig. 2). In Electronic Gallery (1983), a television monitor broadcasts more of the same, this time generated by a computer program that Djordjević wrote during his time at MIT’s Visible Language Workshop. Emerging from Belgrade’s conceptualist scene in the mid-1970s and exhibiting copies of Mondrian and Malevich in New York and Washington, D.C., in the early to mid-1980s, Djordjević completely disappeared from the art world by 1985. His approach to the copy was, thus, more iconoclastic than, for example, that of Sherrie Levine, the New York-based artist of the Pictures Generation who first exhibited her more delicate and market-friendly copies after Malevich and his student Ilya Chashnik in 1984 at a commercial gallery in New York’s East Village.

First shown in 1915 at The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0.10 in a private Petrograd gallery, Black Square reappears in multiple guises here. For Malevich, the painting stood for the ideal of zero form yet was never associated with entropy, becoming instead a limitless space where all readymade structures were cleared away. Along with the circle, cross, and other non-objective motifs, the square provided Djordjević witha recognizable modernist unit that was easy to copy and make a key element in a story about the copy. Indeed, any account of Yugoslav appropriation begins with the former Belgrade artist, who is here represented by six projects including “K.M.” Copies (1980), a salon-style hanging of ten deliberately amateurish copies painted off-center on larger pieces of hardboard (fig. 2). In Electronic Gallery (1983), a television monitor broadcasts more of the same, this time generated by a computer program that Djordjević wrote during his time at MIT’s Visible Language Workshop. Emerging from Belgrade’s conceptualist scene in the mid-1970s and exhibiting copies of Mondrian and Malevich in New York and Washington, D.C., in the early to mid-1980s, Djordjević completely disappeared from the art world by 1985. His approach to the copy was, thus, more iconoclastic than, for example, that of Sherrie Levine, the New York-based artist of the Pictures Generation who first exhibited her more delicate and market-friendly copies after Malevich and his student Ilya Chashnik in 1984 at a commercial gallery in New York’s East Village.

In 1989, Goran Djordjević reappeared briefly under the pseudonym “Adrian Kovacs” to initiate Moscow Portraits (1991), a collaborative copying project that involved amateur painters from Moscow and Belgrade, as well as NSK’s painter-group IRWIN, Marina Grzinic and Aina Šmid, and Mladen Stilinovi?, among others. Reading from a Malevich catalogue with Eight Red Rectangles reproduced on the cover, Kovacs posed for six painters that worked on Moscow’s Arbat Street, then returned to Belgrade to solicit six more copies from amateurs in the local cultural group “Jedinstvo,” producing a pool of twelve “originals” in color and twelve black-and-white copies. Kovacs’s collaborators responded to the assigned motif in media as varied as painting and video, though the results are represented here only through a small catalogue and photographs of the Zagreb and Ljubljana exhibitions. Marking the collapse of post-Titoist Yugoslavia as a common national identity, Moscow Portraits anticipates IRWIN’s later mapping of a “retro-avant-garde” network along similar lines that would posit the Belgrade Malevich as no less crucial a reference than his Russian counterpart.(This refers to the 1994 exhibition “Retroavantgarde” at Visconti Fine Arts Kolizej in Ljubljana that featured IRWIN, Stilinovi?, and the Belgrade Malevich.)

In 1985, Kazimir Malevich reappeared after being dead for 50 years to restage his contribution to The Last Futurist Exhibition in a Belgrade apartment, albeit with slight changes—for example, visitors here encountered needlepoint versions of Black Square and Eight Red Rectangles (1915), as well as a classical Discobolus statue with a black cross painted on his white discus (fig. 3). The display, which travelled the following year to Ljubljana’s ŠKUC, is here accompanied by a letter published in a 1986 issue of Art in America where the Belgrade Malevich responds with surprise at the recent influx of imitators in New York galleries (including the Chinese-American David Diao), and wonders how a single installation photograph could become more important than the pictured artworks.(Kazimir Malevich, “A Letter from Kazimir Malevich,” Art in America (September 1986), p. 9.)

In 1985, Kazimir Malevich reappeared after being dead for 50 years to restage his contribution to The Last Futurist Exhibition in a Belgrade apartment, albeit with slight changes—for example, visitors here encountered needlepoint versions of Black Square and Eight Red Rectangles (1915), as well as a classical Discobolus statue with a black cross painted on his white discus (fig. 3). The display, which travelled the following year to Ljubljana’s ŠKUC, is here accompanied by a letter published in a 1986 issue of Art in America where the Belgrade Malevich responds with surprise at the recent influx of imitators in New York galleries (including the Chinese-American David Diao), and wonders how a single installation photograph could become more important than the pictured artworks.(Kazimir Malevich, “A Letter from Kazimir Malevich,” Art in America (September 1986), p. 9.)

Through a strategy known as the “retro-principle,” IRWIN’s long-running series of paintings in Was ist Kunst? (1984– ) juxtaposes countless signifiers from clashing aesthetic and political regimes of meaning. Whether modernist or classicist, communist or fascist, these mutually deconstructive signifiers never settle into any kind of semiotic order. Although none of these paintings are on view at the City Art Gallery, many can be seen at the concurrent NSK retrospective. Here, one finds instead IRWIN’s The Corpse of Art (2003), a mixed-media installation described by the artists as a “[r]econstruction of Kazimir Malevich in his coffin, made according to Suetin’s plan, as he was exhibited at the House of the Union of Artists in Leningrad in 1935.” The centerpiece is the wax likeness lying in the open Suprematist coffin; decorated with a black square and circle, the coffin’s lid rests against the wall to the effigy’s right, while a dying lily arrangement has been placed to its left (fig. 4). The Black Square hangs directly above its head. As IRWIN’s Borut Vogelnik explains on a didactic panel, The Corpse of Art retroactively completes Malevich’s unrealized vision for a funeral-turned-installation: “Malevich’s corpse found itself at the crossroads of two symbolic fields—the ritual of a burial ceremony, and the ritual of an exhibition opening—and the set of principles and rules that formulate these two fields.” Complicating the narrative further, Hommage à Malevich places loosely related contemporary work by Radenko Milak before IRWIN’s installation. Titled 15 May 1935 (2015), two delicate black-and-white watercolors from Milak’s 365 series, also called Images of Time, reproduce the famous photograph of Malevich lying in state and a photograph of IRWIN’s reconstruction. Adapting his hyperrealist approach to a challenging medium, the Travnik-born Milak gives visual form to the temporal interval between the funeral and its recognition as a work of art.

Through a strategy known as the “retro-principle,” IRWIN’s long-running series of paintings in Was ist Kunst? (1984– ) juxtaposes countless signifiers from clashing aesthetic and political regimes of meaning. Whether modernist or classicist, communist or fascist, these mutually deconstructive signifiers never settle into any kind of semiotic order. Although none of these paintings are on view at the City Art Gallery, many can be seen at the concurrent NSK retrospective. Here, one finds instead IRWIN’s The Corpse of Art (2003), a mixed-media installation described by the artists as a “[r]econstruction of Kazimir Malevich in his coffin, made according to Suetin’s plan, as he was exhibited at the House of the Union of Artists in Leningrad in 1935.” The centerpiece is the wax likeness lying in the open Suprematist coffin; decorated with a black square and circle, the coffin’s lid rests against the wall to the effigy’s right, while a dying lily arrangement has been placed to its left (fig. 4). The Black Square hangs directly above its head. As IRWIN’s Borut Vogelnik explains on a didactic panel, The Corpse of Art retroactively completes Malevich’s unrealized vision for a funeral-turned-installation: “Malevich’s corpse found itself at the crossroads of two symbolic fields—the ritual of a burial ceremony, and the ritual of an exhibition opening—and the set of principles and rules that formulate these two fields.” Complicating the narrative further, Hommage à Malevich places loosely related contemporary work by Radenko Milak before IRWIN’s installation. Titled 15 May 1935 (2015), two delicate black-and-white watercolors from Milak’s 365 series, also called Images of Time, reproduce the famous photograph of Malevich lying in state and a photograph of IRWIN’s reconstruction. Adapting his hyperrealist approach to a challenging medium, the Travnik-born Milak gives visual form to the temporal interval between the funeral and its recognition as a work of art.

Where IRWIN paradoxically envisions the “corpse of art” as something revitalized through its location inside the gallery, other artists frame their borrowed iconography in more sinister terms. For instance, in 1991, Dragoljub Raša Todosijevi? painted over a 1977 cover of Artforum that reproduces Malevich’s Hieratic Suprematist Cross (c.1920–21), adding a skull-and-crossbones flanked by flames, as well as the phrase “Gott liebt die Serben”—German for “God loves the Serbs”—in upside-down script at the base of the cross. In an autobiographical statement reproduced on the wall, the Serbian artist recounts being misunderstood by his professors at Belgrade’s Academy of Fine Arts, calling it a den of “mediocrities, sycophants and vainglorious oddballs,” and then waiting 30 more years to receive a studio from the state—one located on the site of a former German concentration camp, no less. Through the loaded mediation of the Artforum cover, Todosijevi? applies the old oppressor’s language to a nationalist slogan dripping in homegrown fascism, inverting Malevich’s secularized allusion to divine infinity into a protest against the rule of President Miloševi?.

In the next room, Mladen Stilinovi? deals with “dead” signs similarly infused with sinister life in 78 variously sized works on paper and cardboard that are hung salon-style on a single wall (fig. 5). Exploitation of the Dead (1984–2010) puts motifs like the black cross and red star on equal footing through an act of disassociation. The Croatian artist has described working with “not-my-pictures” and “not-my-words,”(Mladen Stilinovi?, “Footwriting [1984],” in Dubravka Djuri? and Miško Šuvakovi?, eds, Impossible Histories: Historical Avant-gardes, Neo-avant-gardes, and Post-avant-gardes in Yugoslavia, 1918–1991 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003), p. 573.) as he plunders the obsolete pictorial languages of “the Russian avant-garde, socialist realism, and the geometric abstraction that emerged in Yugoslavia in the 1950s.”(Kresimir Purgar, “Mladen Stilinovi?: Ideological Necrophilia,” Flash Art International 167 (November 1992), p. 64.) This might involve, for example, cutting up black-and-white images of industrial machinery and combining them with black and brightly colored polygons, crossing references to proletarian life with allusions to non-objective painting.

In the next room, Mladen Stilinovi? deals with “dead” signs similarly infused with sinister life in 78 variously sized works on paper and cardboard that are hung salon-style on a single wall (fig. 5). Exploitation of the Dead (1984–2010) puts motifs like the black cross and red star on equal footing through an act of disassociation. The Croatian artist has described working with “not-my-pictures” and “not-my-words,”(Mladen Stilinovi?, “Footwriting [1984],” in Dubravka Djuri? and Miško Šuvakovi?, eds, Impossible Histories: Historical Avant-gardes, Neo-avant-gardes, and Post-avant-gardes in Yugoslavia, 1918–1991 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003), p. 573.) as he plunders the obsolete pictorial languages of “the Russian avant-garde, socialist realism, and the geometric abstraction that emerged in Yugoslavia in the 1950s.”(Kresimir Purgar, “Mladen Stilinovi?: Ideological Necrophilia,” Flash Art International 167 (November 1992), p. 64.) This might involve, for example, cutting up black-and-white images of industrial machinery and combining them with black and brightly colored polygons, crossing references to proletarian life with allusions to non-objective painting.

If the exhibition’s first floor mostly tracked the more historical references to Malevich, the second floor connected this legacy with more recent developments. In Deflated Image (2014), Ištvan Išt Huzjan pairs a found wooden stretcher with a deflated inner tube from a bicycle. This Ljubljana-born artist interprets Suprematism’s zero form literally as he refers poetically to nostalgia for the first avant-garde. The rubber tube covers only the frame’s outer edges and, thus, cannot provide a painting surface. Yet even as a useful object now transformed into something useless, it still evokes Malevich’s pictorial morphology, calling on the viewer to imagine blowing into the tire’s valve to re-inflate the Suprematist picture and restore it to its lost utopian course.

In other works, the same motifs are inscribed directly on the body of the artist. Serbian Tanja Ostoji?, known for her explorations of gender and sexuality in the context of her country’s ongoing negotiations for EU entry, enacts her own corporeal form as a sexualized commodity that opens closed borders. In the black-and-white photo-series Personal Space (1995–96), Ostoji? covered herself in white powder and was shot from different angles with squares shaved into the back of her head (fig. 6). At the 2001 Venice Biennale, she reserved the black square shaved into her pubic area for Harald Szeemann’s eyes only; in an ironic bid for inclusion, she accompanied the director for the duration of the Biennale’s opening, acting as a kind of escort.

In other works, the same motifs are inscribed directly on the body of the artist. Serbian Tanja Ostoji?, known for her explorations of gender and sexuality in the context of her country’s ongoing negotiations for EU entry, enacts her own corporeal form as a sexualized commodity that opens closed borders. In the black-and-white photo-series Personal Space (1995–96), Ostoji? covered herself in white powder and was shot from different angles with squares shaved into the back of her head (fig. 6). At the 2001 Venice Biennale, she reserved the black square shaved into her pubic area for Harald Szeemann’s eyes only; in an ironic bid for inclusion, she accompanied the director for the duration of the Biennale’s opening, acting as a kind of escort.

In Black Peristyle (1998), Croatian Igor Grubić referenced Suprematism obliquely by responding to the legendary Red Peristyle (1968), an illegal intervention at Split’s Diocletian’s Palace where an initially anonymous local artist group painted the twelve squares of the main courtyard red in another reference to communism. Just as the earlier artists were condemned by both the authorities and the public for defacing a historical monument, Grubić’s then-anonymous use of black paint to make a circular stain in the same spot was no less provocative (fig. 7). The exhibition’s wall text clarifies that Grubić conceived of the Roman site “as a magic mirror [that] reflects the state of society’s conscience,” and of the action as a months-long “media game” that challenged him to “keep public interest in the protest alive.” A few months after the work was awarded second place at the 33rd Zagreb Salon in 1998, the artist’s identity became public knowledge, leading to a vandalism charge, later dropped when it was revealed that Grubić had used water-soluble paint, not the widely reportedly tar.

While Ostoji? would later reinvest Malevich’s non-objective forms with connotations of sexuality as the ex-Yugoslav woman’s ticket to “enlightened” Europe, Grubić turned Malevich’s freed circle into the traumatic stain of recent Croatian history. In a less confrontational register than either of these artists, Serbian Vladimir Nikoli? recodes Suprematism as a subtle form of institutional critique in Painting (2009), a roughly 11-minute silent video easily mistaken for a children’s program. Transforming a white studio into a three-dimensional painterly surface, Nikoli? was filmed from above as he manipulated large geometric cut-outs into familiar-looking compositions; the scene always ends with him crouching under the largest shape, as if to efface his own manipulations on the scene.

Nikoli? is clearly not alone in pointing to Suprematism’s use value as more than just another art-historical reference. For generations of artists working in Yugoslavia’s final decades and in the wake of its collapse, Malevich provided a means to revitalize the “corpse of art” as an anti-ideological tool rather than a formalist trope. Scattered across these shared territories and later separated by new political alignments, artists identified with Malevich as they dis-identified with the watered-down modernism being taught in fine-art academies, communism’s markers of officialdom, and the resurgence of old nationalisms and religious movements. Representing far more than a pictorial ideal of non-objective harmony, this common point of identification helped artists to develop unofficial yet durable networks in an environment without a proper art market and reliable institutional support.