Manuals for Public Space: An Investigation and Intervention into Public Space

Since 2006, Matej Vakula has researched and documented the increased surveillance and politicization of public space throughout the globe, from Slovakia, Poland, and the Czech Republic to Boston and New York City. Observing how public space serves the interests of the public less and less, and how spaces that were once public are now claimed and held by private and government factions, Vakula was inspired to create Manuals for Public Space (MfPS). Rooted in open-source philosophy, MfPS is a participatory multi-platform project (based in Brooklyn and Slovakia) that includes interventions, an interactive blog and website, and printed manuals that outline ways to reclaim spaces that are no longer public, and to make existing public spaces more accessible and respondent to community needs. In the following text, Vakula writes about MfPS and the historical roots of the project.

The idea for Manuals for Public Space took shape in 2011, but the roots of the project go back to 1996 when I was a young graffiti artist. It was during this time that I started to realize the connections between having space and making art. In art school, around 2006, I naturally started to think about public space in wider perspectives, in relation to information, history, politics, the environment and the social. I grew up in a country (Czechoslovakia, and later Slovakia), where notions of public and private space and property and human rights changed due to the political circumstances brought about by the wars, the years of Communist rule, and finally the Velvet Revolution in 1989. This has included changes in thinking about the natural environment, which has gone from being perceived as a space that was relatively open and free to one that is controlled by government and private interests.

Living in a time of accelerated privatization, I am exploring and observing, through my work, how this privatization is influencing public space as well as how public space is influencing its dwellers and users. My work on the project includes research about specific sites that have been in the process of being privatized. I am also interested in the process of commissioning and placing public art. A research project produced under the Manuals for Public Space umbrella was Out and Up to Date. It concerned the openness and fairness of public art commissions by cities and government in Slovakia, and will soon be published on the MfPS website. In a related project, “Prize for the Best and for the Worse Public Artwork,” I organized a panel of museum curators, art center directors and writers as part of a two-day conference/discussion in Bratislava, which was open to the public. We had round-table discussions about major public art pieces throughout Sovakia and then named the worst and best public art, along with explanations of what makes good public art. This has made what was once a closed process transparent. The system originally operated in the same way that it did during communism, with commissions given to a few pre-chosen artists who abide by certain rules and tastes. “Prize for the Best and Worse Public Artwork” resulted in a countrywide effort among arts professionals to create an open system for selecting artists for public art commissions.

Living in a time of accelerated privatization, I am exploring and observing, through my work, how this privatization is influencing public space as well as how public space is influencing its dwellers and users. My work on the project includes research about specific sites that have been in the process of being privatized. I am also interested in the process of commissioning and placing public art. A research project produced under the Manuals for Public Space umbrella was Out and Up to Date. It concerned the openness and fairness of public art commissions by cities and government in Slovakia, and will soon be published on the MfPS website. In a related project, “Prize for the Best and for the Worse Public Artwork,” I organized a panel of museum curators, art center directors and writers as part of a two-day conference/discussion in Bratislava, which was open to the public. We had round-table discussions about major public art pieces throughout Sovakia and then named the worst and best public art, along with explanations of what makes good public art. This has made what was once a closed process transparent. The system originally operated in the same way that it did during communism, with commissions given to a few pre-chosen artists who abide by certain rules and tastes. “Prize for the Best and Worse Public Artwork” resulted in a countrywide effort among arts professionals to create an open system for selecting artists for public art commissions.

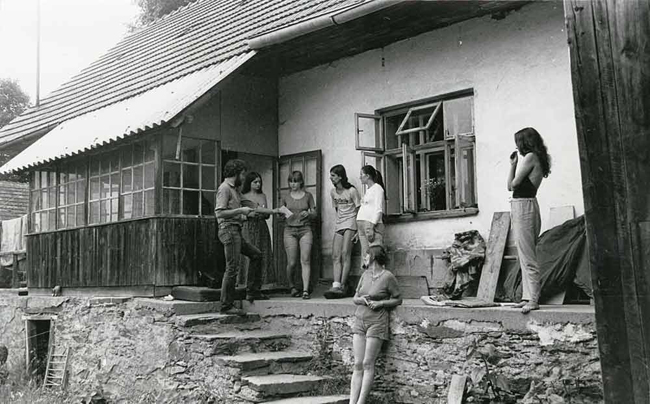

Observing the role played by the community and the sense of commonality between people, I see a division between the former Eastern and Western Europe. In the West, the community, or a sense of commonality, exists more often than in Eastern Europe, an area that is still, in many ways, recovering fromyears of rule under an oppressive communist regime that destroyed almost all community with a shared purpose. (One by-product of communism, however, was the formation of a new community of dissidents.) This had an impact on how people used and thought of public space. In towns and villages, people’s use of public space was restrained, where in the mountains, woods, and the countryside people felt more free and safe from the watching eyes of the secret police. In the countryside, artists produced exhibitions and black-listed musicians held concerts. In the former Czechoslovakia there was an organized system for presenting illegal rock concerts in rural locations. The countryside and woods were places of dissent and, therefore, were also politicized.

Observing the role played by the community and the sense of commonality between people, I see a division between the former Eastern and Western Europe. In the West, the community, or a sense of commonality, exists more often than in Eastern Europe, an area that is still, in many ways, recovering fromyears of rule under an oppressive communist regime that destroyed almost all community with a shared purpose. (One by-product of communism, however, was the formation of a new community of dissidents.) This had an impact on how people used and thought of public space. In towns and villages, people’s use of public space was restrained, where in the mountains, woods, and the countryside people felt more free and safe from the watching eyes of the secret police. In the countryside, artists produced exhibitions and black-listed musicians held concerts. In the former Czechoslovakia there was an organized system for presenting illegal rock concerts in rural locations. The countryside and woods were places of dissent and, therefore, were also politicized.

There has been a rebirth of this escapism into nature today, influenced by the economic, social and ecological situation. This escapism is an “unspoken manifesto of the spiritual atmosphere of current society,” write curators Katarína Slaninová and Vanda Sepová.(Katarína Slaninová and Vanda Sepová, “Bonaj Lokoj,” 2013, exhibition at Prádelna Bohnice, Bohnice, Czech Republic, http://www.pradelnabohnice.cz/?p=267.) With both positive and negative connotations, escapisms “are also acts and activities pushing the state of society, as a catalyst of progress, forward. And it is art that could become one of these tools of change.”(Ibid.) In this way, nature can become a gathering place where knowledge or information is shared and then transformed into action that might help restore and preserve the environment.

There has been a rebirth of this escapism into nature today, influenced by the economic, social and ecological situation. This escapism is an “unspoken manifesto of the spiritual atmosphere of current society,” write curators Katarína Slaninová and Vanda Sepová.(Katarína Slaninová and Vanda Sepová, “Bonaj Lokoj,” 2013, exhibition at Prádelna Bohnice, Bohnice, Czech Republic, http://www.pradelnabohnice.cz/?p=267.) With both positive and negative connotations, escapisms “are also acts and activities pushing the state of society, as a catalyst of progress, forward. And it is art that could become one of these tools of change.”(Ibid.) In this way, nature can become a gathering place where knowledge or information is shared and then transformed into action that might help restore and preserve the environment.

Today, the biggest challenge in Central and Eastern Europe is, I believe, rebuilding a sense of commonality and creating new communities that, in turn, are able to re-engage with public space. Many of the groups who participate in my workshops are producing manuals that detail ways to create or protect green spaces in the city through interventions in unused public spaces. For example, in the Czech city of T?ebo?, a workshop led to a manual and then the construction of a garden for senior citizens living in a cluster of apartment blocks, giving this community the ability to spend meaningful outdoor time together taking care of and harvesting plants. This action also created a sense of commonality and community, which is a hopeful sign that individuals and public space can have a positive impact on each other. In each of the MfPS workshops I have discovered that people desire to come together under a unified purpose to make a meaningful contribution to their city or town, illustrating what is, perhaps, the most important aspect of the MfPS project: creating a public space that is, by design, a place where communities come together and produce change at a local level. By sharing information, plans and results, I hope to create a wave of small actions around the globe that encourage society to create, maintain, and protect new public spaces, helping to put an end to the trend of privatization that has contributed to the shrinking of public space around the world. ??????????? ????????? ????? – ???????????? ??????? ????????? ?? 4,5 ?????? ?? ?????, ????????.

Today, the biggest challenge in Central and Eastern Europe is, I believe, rebuilding a sense of commonality and creating new communities that, in turn, are able to re-engage with public space. Many of the groups who participate in my workshops are producing manuals that detail ways to create or protect green spaces in the city through interventions in unused public spaces. For example, in the Czech city of T?ebo?, a workshop led to a manual and then the construction of a garden for senior citizens living in a cluster of apartment blocks, giving this community the ability to spend meaningful outdoor time together taking care of and harvesting plants. This action also created a sense of commonality and community, which is a hopeful sign that individuals and public space can have a positive impact on each other. In each of the MfPS workshops I have discovered that people desire to come together under a unified purpose to make a meaningful contribution to their city or town, illustrating what is, perhaps, the most important aspect of the MfPS project: creating a public space that is, by design, a place where communities come together and produce change at a local level. By sharing information, plans and results, I hope to create a wave of small actions around the globe that encourage society to create, maintain, and protect new public spaces, helping to put an end to the trend of privatization that has contributed to the shrinking of public space around the world. ??????????? ????????? ????? – ???????????? ??????? ????????? ?? 4,5 ?????? ?? ?????, ????????.

Matej Vakula is a Slovak artist and educator, exhibiting internationally, including in the United States. He was Fulbright scholar at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design and at MIT (2009-2011). In 2012, Vakula was one of the few Slovak artists to represent Slovakia at the Sixth International Prague Biennial of Contemporary Art. He has taught at the Academy of Fine Arts in Bratislava, Slovakia and also contributes critical writing about art and culture to art magazines. Vakula’s artwork has been published in books about Slovak contemporary art. He lives and produces work between Brooklyn, New York, and Žilina, Slovakia. See http://vakula.eu/photodocumentation.html.

Matej Vakula is a Slovak artist and educator, exhibiting internationally, including in the United States. He was Fulbright scholar at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design and at MIT (2009-2011). In 2012, Vakula was one of the few Slovak artists to represent Slovakia at the Sixth International Prague Biennial of Contemporary Art. He has taught at the Academy of Fine Arts in Bratislava, Slovakia and also contributes critical writing about art and culture to art magazines. Vakula’s artwork has been published in books about Slovak contemporary art. He lives and produces work between Brooklyn, New York, and Žilina, Slovakia. See http://vakula.eu/photodocumentation.html.