György Galántai and Júlia Klaniczay, eds., “Artpool: The Experimental Art Archive of East-Central Europe” (Book Review)

ARTPOOL THE EXPERIMENTAL ART ARCHIVE OF EAST-CENTRAL EUROPE, GYÖRGY GALÁNTAI AND JÚLIA KLANICZAY, EDS., BUDAPEST: ARTPOOL, 2013, 536 PP.(The PDF version of the publication can be downloaded free from: http://www.artpool.hu/2013/Artpool_book_en.html.)

The importance of this long overdue autobiographical volume by Artpool, the Budapest “Experimental Art Archive of East-Central Europe” is hard to overestimate. Archivists György Galántai and Júlia Klaniczay, who double as the book’s authors and editors, account for both a Hungarian and widely international presence in and around Artpool’s orbit. Art historian Kristine Stiles strikes a personal and professional chord in her pithy and highly appreciative Introduction, rightly calling the book “a milestone in the history of art for its documentation of a remarkable period,” and points out that Artpool is both an artwork and an archive (p. 8).

It is an ongoing project, indeed, further developed and sustained by Galántai and Klaniczay, who have been shaping Artpool’s profile by organizing and navigating its international network. They developed personal contacts and long-lasting friendships with such partners as Anna Banana (b. 1940), Ken Friedman (b. 1949), Ben Vautier (b. 1935), Michael Bidner (1944-1989), Guglielmo Achille Cavellini (1914-1990), Ugo Carrega (b. 1935), Adriano Spatola (1941-1988), Ray Johnson (1927-1995), Peter Frank (b. 1950), and hundreds of other alternative artists on the international scene. Their collaboration with mail art, performance, and Fluxus artists and critics bears the archivists’ personal touch as well. The great number of Hungarian artists, critics, and theorists they brought together include Miklós Erdély (1928-1986), Tamás Szentjóby (presently called St. Turba, b.1944), Géza Perneczky (b. 1936), Endre Tót (b. 1937), János Vet? (b. 1953), and countless others, whom they also integrated into the international network, facilitating the exchange of ideas and research. Their inventing, organizing, and documenting of events were priceless contributions to the Hungarian neo-avant-garde scene throughout the 1970s, and up to today. The collection of writings and documents in this volume stretches from the prehistory of Artpool to a year-by-year illustrated account of the archive from 1979 to 2011, ending with a list of practical information that indicate the archive’s present vitality, continued activities, and standing invitation for all creative minds to participate.

It is Galántai and Klaniczay’s intense personal presence and guardianship that gives Artpool its unique character, which also comes across in the present documentary volume. As Stiles underlines, Artpool is a unique institution in more than one way. It grew out of its founder, artist György Galántai’s passion to document the elusive events and artistic production resulting from the alternative artistic activities in Hungary since the late 1960s. This initial documentation was Galántai’s response to the alternative artists’ fugitive status during the Cold War era. His efforts to preserve, at least, the memory of those countercultural activities that would, otherwise, have disappeared without a trace, was a triumph. In “A Personal Account” (pp. 16-21), Galántai relates that the origins of the archive began with the documentation of the events at the Chapel Studio at Balatonboglár, one of the most important chapters of dissident art in Hungary. Galántai operated the Chapel Studio from 1970 to 1973 as an art space. He first reached out to an international group of mail artists in 1978.

Renting an out-of-use funeral chapel and the surrounding lot was a unique initiative that tested the boundaries of legitimacy in communist Hungary. Galántai signed a lawful contract and abided by it, which gave him the right to use the rented space at his discretion. However, when he invited experimental artists, theater groups, and musicians (eventually also from neighboring countries), these activities came under police scrutiny and were forcefully banned in 1973, accompanied by a derogatory article in the leading Hungarian daily paper, titled “Happening in the Crypt,” that depicted Galántai’s undertaking as creepy and sick. In fact, the short time of the Chapel Studio’s existence went a long way to sustain the experimental artists’ community in Hungary. Its detailed history is the subject of a previous publication,(Klaniczay, Júlia, Sasvári, Edit, eds., Törvénytelen avantgárd. Galántai György balatonboglári kápolnam?terme 1970-1973 (Illegal avant-garde. The Chapel Studio of György Galántai at Balatonboglár 1970-1973), Budapest: Artpool-Balassi, 2003.) so it suffices to note here that it has come down in memory as a fascinating golden moment of free experimentation and self-expression shared by a very diverse crowd of artists at a place they felt was safe and innovation friendly.

It was widely known at the time that censorship in Hungary focused on Budapest and the “grands arts,” while in small towns exciting new experimental textile art and ceramics emerged already in the late 1960s. Going to sleepy, lakeside Balatonboglár, which was not on the official radar (at least for some time), was therefore a congenial idea – a summer vacation for all participants in every sense. This was possible only during those post-1968 years when Hungary’s political leadership was divided about having participated in the invasion of Czechoslovakia. They issued contradictory messages that condemned the Czech reforms and, at the same time, suggested that Hungary was also following the path of such reforms, but less “drastically.” The forceful closing of the Chapel Studio marked the return to hardline politics in Hungary in the wake of the November 1972 resolution by the ruling party, and it was a prelude to the emigration of artists, philosophers, and sociologists whom the political system wanted to get rid of rather than sanction them at home. From this point on, Galántai and the 1979-founded Artpool archive operated in illegality.

Illegality, however, did not mean hiding. On the contrary: in May 1980, Artpool appeared in Budapest’s Heroes’ Square, the most visible point in the city that Galántai rightly calls “the nation’s theater” (p. 54). Galántai and Klaniczay, clad in white, posed as the striding worker-and-peasant pair of Soviet sculptor Vera Mukhina’s emblematic 1937 Moscow statue, in stark contrast to the circle of historic kings of Hungary behind them. While the artists were holding high a book with a reproduction of Mukhina’s original statue, in which a worker and peasant woman hold a hammer and a sickle, fellow artist Guglielmo Achille Cavellini was busy writing the names of outstanding artists on their white clothes. Turning Socialist Realism inside out, this performance epitomized the satirical and independent stance of Artpool, which has been critical, rebellious, and nonviolent ever since.

Galántai realized early on that participation in the international mail art movement required an institutional identity, hence the name Artpool, a term that “refers to the act of collecting from diverse artistic spheres and endeavors” (p. 17). While corresponding with foreign artists was not unlawful in Hungary, every international activity was closely monitored. Artpool used the postal service as its medium, but it had to do so carefully. First, Galántai sent out hundreds of mailings in one package to Michael Scott in Liverpool, who could distribute them out of England. Later and mindful of the police’s attention, Galántai mailed letters from many different Budapest mailboxes, careful not to send too many from one location.

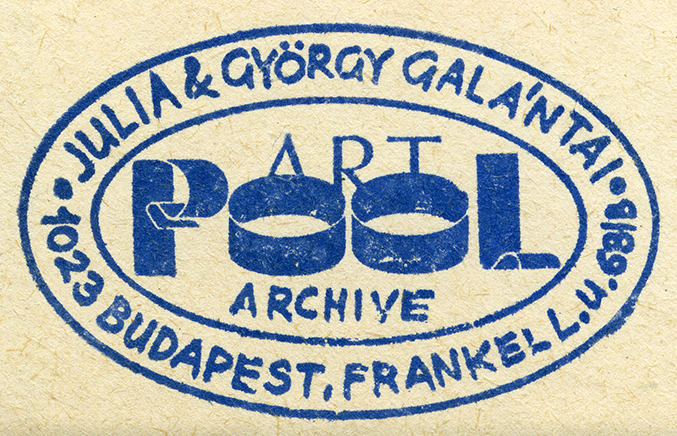

Mail art created an invisible, new dimension in the pre-Internet era. It was a continuously growing network with a flow of mail inserted into the international postal service’s circulation that it used for creating its own alternative space. Imaginative and playful rubber stamps, often many on the same envelope were designed and became a staple of mail art. Artpool’s own announcements came with their beautiful, oval-shaped rubber stamps on envelopes that I personally cherished and collected. A look at such an envelope was enough to see that Artpool had its own identity.

Mail art created an invisible, new dimension in the pre-Internet era. It was a continuously growing network with a flow of mail inserted into the international postal service’s circulation that it used for creating its own alternative space. Imaginative and playful rubber stamps, often many on the same envelope were designed and became a staple of mail art. Artpool’s own announcements came with their beautiful, oval-shaped rubber stamps on envelopes that I personally cherished and collected. A look at such an envelope was enough to see that Artpool had its own identity.

With the overuse of rubber stamps in tongue-in-cheek seriousness, mail art mimicked the state bureaucracies. “Stampart” and “stampartist” were new terms for the designers of new, artistic stamp sheets that were used as decorations and exhibition objects: nonofficial entities that appeared as alternatives to officially issued stamps. Mail art was a triumph over the many actual and symbolic borders that separate the countries of the world, the system of exit and entry visas, the particular difficulties involved in traveling out of Soviet Bloc countries, and the geographic distances that were not easy to overcome at the time.

No matter how circumspect, Galántai repeatedly drew the attention of the authorities. The Hungarian secret service conducted investigations in order to control his activities through embedded informers, by bugging his apartment and phone, and by censoring his correspondence. The informers’ observations were quite often so revealing that today they almost read as acknowledgments. In 1983, Galántai launched one of his periodicals, AL (abbreviation for Aktuális Levél or Actual Letter, but also understood as Alternative Letter, Artpool Letter). A “top secret'” report by a police informer stated:

During the period between 1970 and 1973, when Galántai was active in Balatonboglár, he was already playing a decisive organizational, community-forming role. He brought together and connected the divided and isolated “avant-garde” groups from the fine arts and to a lesser degree from theater, film, music and literature. On occasion, this activity even extended to Hungarian artists abroad (e.g. in Yugoslavia). However, the publication titled AL far more efficiently performs this task. […] The various gatherings are forgotten […] but the new periodical keeps 200-250 individuals in contact with one another on a permanent basis. […] News of events, which would otherwise remain the private affairs of 3-4 people, now reach hundreds and their ripple effect gives rise to further debates. […] The information published in AL will increase the number of meetings between individuals, and – setting in motion a chain reaction – it will forge together the avant-garde circles which until now have been dispersed. (See, pp. 113-114).

Below, a surprisingly accurate police report, dated September 1983, also offers an assessment of Artpool that clearly acknowledges its merits:

In Hungary, Artpool is a unique documentation, which, if objectively analyzed and made more broadly available to a wider audience and, indeed, to circles of researchers and art historians, could provide the opportunity for a thorough survey of the fine arts’ aspirations in Western countries. The work that Galántai has invested in the development, organization and obtaining of the pieces of the collection is significant in regard to both quantity and quality… (See, p. 115).(Translated by Krisztina Sarkadi-Hart.)

The report ends, as is to be expected, by declaring that the publication of AL is hostile to the cultural policy of Hungary and helps the political opposition; it is, however, remarkable, that the in-depth interest of the secret service in oppositional artistic and intellectual activities during the 1980s seems, in retrospect, to have had a documentary, rather than retaliating purpose: some of the police reports read like items from a different, parallel archive.

After the fall of communism in 1989, Artpool received state support and moved into its present location in a central part of the city, a move made possible, in 1991, by Budapest’s liberal mayoral office. Fully legitimate and highly visible, since then the archive has developed a great deal and expanded its activities. Galántai has carried out an impressive number of curatorial projects that have taken the form of exhibitions and festivals in various media including, among others, mail art, mail film, sound performance, and symposia. The characteristic visual form of Artpool’s exhibits has been consistently playful, Dada-like, and mixed media: rich in print, photo, video (both analog and digital), and in found objects. The shows have also been idiosyncratic, disorderly, intransigent, cartoonish, absurd, repetitive, happenstantial, and often organized in series.

Galántai’s annual special projects have inspired crowds of alternative artists to join the year’s theme. These curatorial projects developed during the newfound freedom have included retrospective and new projects, for example the reconstruction of the banned 1984 exhibition Hungary Can Be Yours!, a sarcastic demonstration in which Artpool falsified images in the manner of Hungarian officialdom that created images to popularize Hungary. When the fax machine became the new instant vehicle of communication, a “Decentralized Worldwide Networker Congress Budapest Session” was set up in 1992, with the publishing of Artpool Faxzine. The following year was “The Year of Fluxus at Artpool” featuring “one-man shows and group exhibits, meetings, art events, performances, lectures, and research on Fluxus” (p.147). These events were followed by: “The Year of Miklós Erdély (1994), “The Year of Performance” (1995), “The First Year of Internet at Artpool” (1996), “The Year of the Network ” (1997), and “The Year of Installation” (1998). “The Year of Contexts” (1999) was a farewell to the 20th century, while the year 2000, “the zero year of the 21st century,” was declared “The Year of Chance” and featured new projects and Artpool’sparticipation in international events. There was also “The Year of the Impossible” (2001) and the “Year of Doubt/Doubles” (2002), which played on a Hungarian pun. Meanwhile, 2009 was declared “The Year of the Last Number of Artpool.” (For a complete listing of yearly programs see the Artpool URL in footnote 1.) Play today at the best kizi games.

Creating a context for the archive, its contents, and experimental art was Galántai’s longtime pursuit. Talking of the nonfigurative artists of the 1960s, he once said that “they spoke of the need to build two bridges: one toward Europe, the other toward Hungary’s cultural heritage, with the latter entailing “as much [Lajos] Kassák’s constructivism and political non-conformism as the universal values and autonomy of the group called European School [1945-1948].” This was because “the Hungarian happenings of the mid-1960s and conceptual art of the early 1970s owed as much to the Hungarian Dadaists as to the international Fluxus movement” (p. 276).

The present volume offers a chronology of a large number of exhibitions, conferences, off-site activities, publications, concerts, and various other events that Artpool organized. Brief descriptions, reproductions of the exhibited artworks, original announcements of events organized by the archive and a great number of photos make up the chapters, together with the relevant web addresses. Artpool has digitized and posted most of its holdings online, including voice and video items, and prides itself on offering free Internet access to researchers on its premises. This volume is a book, and it isn’t: it’s the tip of an iceberg of data and documents. In light of its rich list of references, it serves as a massive, systematic blueprint of a databank that can back up any inquiry into Artpool’s activities and collections, most of which really only come to life when accessed online.

Artpool, as both an archive and an artwork, testifies to the necessity of creating a cultural space that is free, inclusive, noncommercial, open and independent, one that provides an alternative to most mainstream artistic activities and discourse, but also complements them. The media used in this art space include, to cite Hungarian conceptualist Endre Tót: “postcards, telegrams, letters, envelopes, stamps, rubber stamps, photocopies, faxes, objects, T-shirts, newspapers, electronic message boards, placards/posters, banners, boards, actions, graffiti, audiotapes, film and video” (this list, on p. 242 of the book, is from 1998, which is why it includes items that seem old-fashioned today). Here, aesthetics are subordinated to the artistic process, and experimental art is an umbrella term for most everything that is a product of a reflective or participatory attitude to the world. Claire Bishop calls this attitude the “return to the social, part of an ongoing history of attempts to rethink art collectively.”(Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells. Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship (London, New York: Verso Books, 2012), p. 3.) The art that Artpool collects, documents, and produces is positioned on the margins of this effort. Not activist, but socially alert; not interventionist, but reflective. Artpool, by way of preserving and maintaining a chronicle of experimental art, invites everyone to participate and enjoy the process of thinking, experimenting, making, and expressing.