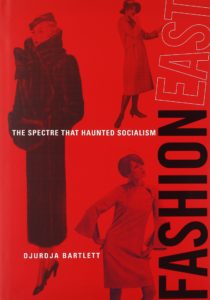

Djurdja Bartlett, “Fashion East: The Spectre that Haunted Socialism”

DJURDJA BARTLETT, FASHION EAST: THE SPECTRE THAT HAUNTED SOCIALISM, CAMBRIDGE, MASS.: THE MIT PRESS, 2010, 344 PP.

Impressive in its scope, beautifully illustrated, and admirable for its depth and breadth of archival research, Djurdja Bartlett’s sumptuous book Fashion East: The Spectre that Haunted Socialism does not in any way disappoint the reader looking for a survey of sartorial history in the Soviet Communist bloc. Bartlett does a magisterial job in traversing the cultural space of Soviet fashion from the 1920s “avant-garde” to the late Soviet era. Extraordinary also is Bartlett’s deftness at integrating the post-WWII fashion histories and discourses from all major East-Central European Soviet nations: East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, and Yugoslavia under the aegis of “socialist sartorial narratives.” Under this umbrella, Bartlett constructs a chronological triad that moves from “utopian dress,” the avant-garde interventions of the 1920s, “socialist fashion,” an era Bartlett imagines running from the 1930s in the Soviet Union and from the 1950s in the Eastern bloc until the 1960s, when, Bartlett claims, “everyday fashion” undermined its master narrative. “Everyday fashion” functions as the hero of Bartlett’s own master narrative; for her, its “do it yourself” attitude overcame the stultification of “ontological conservatism” and championed the socialist woman’s individual creativity.

Within the bounds of this useful but, at times, overly restrictive sequential history, one Bartlett culls first and foremost from Soviet history, the author introduces her research into “East Europe” in Chapter Three by stating that the same grand narrative attends to the Soviet satellites, with the “utopian dress” era occurring in the 1940s. In doing so, she vitiates the value of indigenous socialist avant-gardes of East-Central Europe in the 1920s and 1930s. Though some attempt is made to discuss historical specificities from nation to nation, for example how East Germany, Poland, and Yugoslavia cultivated consumerism in the post-Stalin 1960s, a generally homogenizing story is maintained in Fashion East: “Yet in all East European countries, an essential element of thedeals struck between the regimes and their new middle classes was that freedom and consumer practices should not bring the nature of political rule into question” (184).

The argument of the book is many pronged and relies on a hefty number of claims, questions, and suppositions accumulating to a thesis that ultimately repeats the book’s subtitle: fashion is an open system, a “permanently incomplete phenomenon” (12), socialist discourse a closed one; never could the twain meet. As ever-evolving fashion, for Bartlett, resists the hegemony of a static and stultifying ideology such as “socialism,” of all the many ghosts fashion might be for “socialism,” it seems to me the poltergeist is most fitting, though Bartlett does not carry her metaphor this far.

The dilemma here is in the myriad, sometimes necessary but not sufficient, grounds for this overarching and yet somewhat pat claim. Bartlett acknowledges the establishing work of Roland Barthes in her inquiry, and yet his Fashion System (1967, 1983) makes clear the dangerous closures and snaps of fashion, the bourgeois ideology of its language: “Calculating, industrial society is obliged to form consumers who don’t calculate; if clothing’s producers and consumers had the same consciousness, clothing would be bought (and produced) only at the very slow rate of its dilapidation” (Barthes xi). Beyond the bravura of the thesis claim, Bartlett does, indeed, place more critical pressure on “socialist” and “bourgeois” systems when she identifies the predicament the growing middle class in Soviet post-war society posed for the State, especially given its constitutive heterogeneity—”the new socialist middle classes comprised disparate social strata, mainly those with only a limited knowledge of culture and of its diversified practices” (186). As emblematic as such a moment is of Bartlett’s fluency with her material, it also sets in relief the problematic use of the term “socialist” in Bartlett’s argument. Bartlett relies quite heavily on the term, to the point of constructing her book around a midsection on “socialist fashion,” which she claims was the most perduring and tenacious of three practices, the others being “utopian dress” and “everyday fashion.” The problem with the term “socialism” is that it manifests itself quite early in Bartlett’s treatment and never seems to be settled enough to allow the reader to understand fully the pith of such a term or never fully unsettles enough to allow the reader to apprehend its innate dubiety. With a claim such as “Although socialism eventually invented its own fashion, it was not the genuinely new socialist dress style that the constructivists had dreamt of in the early 1920s” (x), one is left to wonder which socialism is “real,” if Bartlett is arguing for an “authentic socialism” as opposed to a constructed one, and, further, where the line is drawn between fashion as a semiotic system or structuring structure/discourse and fashion as an essentialist phenomenon.

Symptomatic of the commotion of terms and concepts is, perhaps, the glaring lacuna of a discussion of men’s fashion. Illustrations, gorgeous as they are, are almost exclusively those of women’s fashion. The decision to omit any investigation into the “socialist” male sartorial narrative would be understandable, if Bartlett proffered a time-and-limit explanation for its absence, but the fact that she contends that men’s fashion does not evolve as deeply and provocatively as women’s, so it would not be worthwhile to discuss it in this work, does raise a dilemma. While there is a reference to Lenin having won the revolution in a Western suit, not much more is said of the visual icon of Lenin, or Stalin, or the visual discursive strategy under Stalin’s regime (viz, Vladimirov’s famous painterly phantasy, Lenin i Stalin letom 1917-go, where Stalin sits up straight and strong in his iconic militaristic “proletarian” gear beside an ailing Lenin, in his three-piece suit with a blanket thrown over his hunched shoulders). The argument of how much gender construction owes to clothing, a theme treated throughout the book, and how much nostalgia is intertwined with fashion’s changeability, are those that could be more thoroughly exfoliated by admitting men’s fashion into the fold. The discussions of the use of “ethnic and folk motifs” in dress and the eye-opening canvass of DIY fashion under Soviet scrutiny could have been even more significant with illustrations of men’s place in these trends. Revelatory too could be fashion stories from sources other than fashion magazines (cinema, for example), though these are, of course, the most crucial sites for sartorial narratives.

Perhaps one of the most intriguing dichotomies Bartlett constructs to feed her argument is that between myth and fashion. She is very assured in the claim that myth and fashion are mutually exclusive “ideologies.” Myth for Bartlett seems to be tantamount to “socialist” (read: Stalinist) iconography—stabilizing, controlling, conserving of the “Master discourse”—, while fashion is, once again, indeterminate, flexible, even subversive. To this matter, concerning also is the non-problematized binary between what Bartlett calls “modern” or “modernist” fashion and “conservative” dress, a discussion further mired by the lack of critical argument as to what these terms encompass, or even an acknowledgement of the rich controversy as to what constitutes the imaginary of “modernity.” (Bartlett appears to associate the modern with that which changes and is changeable and the “conservative” or traditional with that which preserves the status quo. See, for example, her discussion of “everyday fashion” (11). What is quite clear to the reader is that the “modern” is Bartlett’s undisputed hero, the savior of all closed ideologies qua mythologies.

In a way we’ve returned again to Barthes, this time to his collection Mythologies (1957). For Barthes, the process of myth creation is a conservationist, or conservative, one. Modern mythologies sustain the regnant ideology—”imperialist” or “socialist”—through the ruling class’s media outlets. Fashion, for Bartlett, “is a modernist fast-changing phenomenon immersed in everyday reality, while myth is conservative and traditional, preserving the status quo” (5); in her tale of the sartorial, fashion resists mythologization. Bartlett’s optimism for the fashion system (as a non-system?) is refreshing, but the reader might wonder if the opposition between fashion and myth is truly as hardy as she would have it.