Joanna Malinowska in Conversation with Magdalena Moskalewicz

Polish-born, Brooklyn-based visual artist Joanna Malinowska works mainly in sculpture, video, and performance art. Her projects are often inspired by interest in cultural anthropology and cultural clashes – she traveled to the American Far North to make a video documentary on Jimmy Ekho aka Arctic Elvis – an Inuit folk singer and Elvis Presley impersonator. In one of her early video explorations, Malinowska impersonated a stereotypical Polish cleaning lady and cleaned apartments of New York intellectuals in exchange for private lessons in philosophy. Malinowska’s work has been presented in many solo and group exhibitions in the United States and Europe, most recently as a part of the Whitney Biennial 2012. She is graduate of Yale School of Art /Sculpture Department (MFA 2001) and a recipient of several high profile awards including a 2009 John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship.

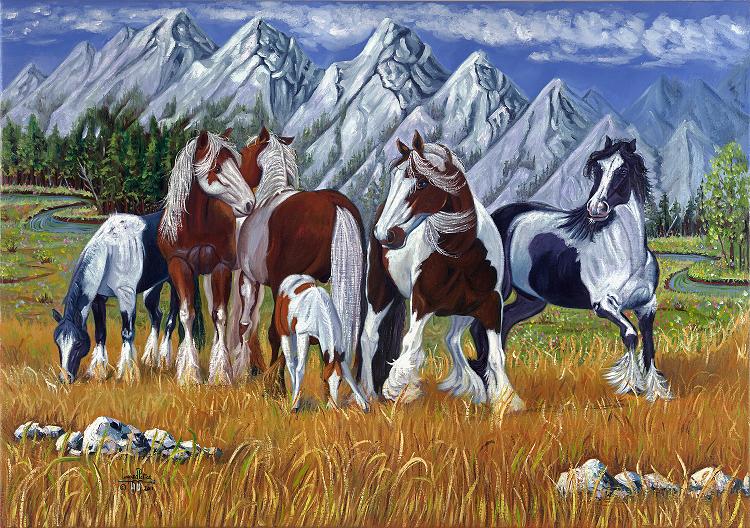

Magdalena Moskalewicz: At the 2012 Whitney Biennial of American Art, in which you participated, you extended your invitation – so to speak – to include a work by Leonard Peltier in your exhibition. A Native American activist and a member of American Indian Movement, Peltier has been imprisoned under a life sentence since 1977, for the alleged murder of two FBI agents. You showed a painting of his featuring wild horses depicted in a realistic manner, which for Peltier are a symbol of much desired freedom. This work stood out in the Whitney Museum galleries.

Joanna Malinowska: I have a different opinion of this piece than most painting experts. I don’t find it as ridiculous and unappealing as many art critics, but the painting in itself was not so important. I was mainly interested in bringing attention to the matter of Peltier’s imprisonment, the way Marlon Brando did in 1973 when he received the Oscar for his performance in The Godfather.

MM: What did he do?

JM: He sent Sacheen Littlefeather, an Apache actress to accept or actually decline the award. It was during a time of protests from the American Indian Movement, and Brando was very supportive of them.

MM: Was there also a link to the Peltier case?

JM: I don’t think there was a direct link to this case. I think it was rather the occupation of Wounded Knee that took place in 1973. This was the site of an infamous massacre that happened there in 1890, where so many people were killed, including children and women. It is one of the most tragic events in the history of America. In the early 1970s there were a lot of riots in this area, and Peltier was one of the leaders of the movement that started it all.

MM: And how did you learn about Peltier in the first place?

JM: I’ve been interested in Native American culture for a long time, even before I came to the United States. So I did extensive reading. Unfortunately, though, the American Indian Movement is not hugely covered in the press, and really only now are certain things coming to light. There is a book, In the Spirit of Crazy Horse written by Peter Matthiesen, that documents the whole story and tries to prove that Peltier was imprisoned unjustly. I do realize this is a complex matter and, in the end, no one knows who really killed those two FBI agents. There are different arguments speaking for Peltier, one of them being that even if hypothetically he had killed these agents the riots that were taking place on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation at the time were almost a war against the American government, and people do get killed in war. A lot of people died on the other side as well. But I personally believe that he didn’t do it because there was a lot of framing going on. There were a lot of trials where they just tried to put somebody in prison just to “get the justice done,” and a lot of corruption, and corrupting witnesses. There is a ton of evidence pointing to Peltier’s innocence.

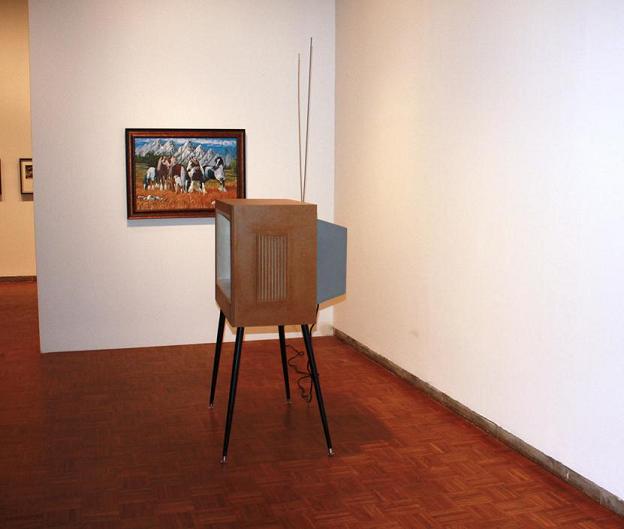

MM: So in order to draw attention to Peltier’s case, you built a wall inside of the gallery and hung his painting there, one of the paintings he now produces in prison. This act is like a statement, as if before there had been no wall in the Whitney that could have accommodated his works.

JM: This wall was just a strategic trick. I wasn’t sure how the curators would react to Peltier’s piece in the show. By having this special wall erected as a part of my installation, I felt I was establishing a piece of a territory where I can do whatever I like. But in the end, the curators actually liked the idea and the painting, so there was no problem.

JM: This wall was just a strategic trick. I wasn’t sure how the curators would react to Peltier’s piece in the show. By having this special wall erected as a part of my installation, I felt I was establishing a piece of a territory where I can do whatever I like. But in the end, the curators actually liked the idea and the painting, so there was no problem.

MM: How did you choose the painting? How did you contact Peltier in the first place?

JM: It was complicated. When I became interested in the whole matter, Peltier was put into so-called “solitary confinement.” There was some story about someone sending him ten British pounds, and it is illegal to send money to prison. It is a rather strange story, but whatever happened, he was kept during the hot summer in solitary confinement without air conditioning, so it was impossible to contact him. It is even very hard to get in touch with him when he is in the general population prison. But there is a strong group of supporters who work for him, who continue to fight for his rights, and I have been in touch with Dorothy Ninham, the chairwoman of the Leonard Peltier Defense Offense Committee.

MM: This is the woman who was contacted through Skype during your performance at the Whitney Museum, and she spoke for him.

JM: Yes. I am slightly disappointed that this matter did not get any attention, other than from a journalist at Bloomberg.com who wrote that the Whitney had a convicted felon in its show.

MM: And that if Larry Gagosian flexed some muscle he might be able to get him out and sell his art.

JM: I feel this is a little bit sad. I don’t know what it says: does it show a state of total insensitivity on the part of American society?

MM: For the same event you arranged for a group of people to howl like wolves following a Skype conversation, and a performance of Moonlight Sonata on two toy pianos. The audience really engaged in the idea and all the people gathered in the lower space of the Whitney howled for some 15 minutes, as if evoking the ambiance of the prairies.

JM: I feel that there is something special about howling. It’s a form of antidepressant, an intense expression or release of something unsayable. Although I wish the howling at the museum had been even louder and lasted longer.

MM: Along with the painting by Peltier you also showed two of your own pieces at the Whitney. One was a bottle rack assembled from mammoth and walrus tusks, a play on the heritage of American/ Western modernism. The other is a video of Joseph Beuys and Hugo Ball appearing to you, as if in a vision, after you drank some kind of magic potion. Did you actually make this potion for the sake of the movie? Or is the cooking that one witnesses in the film staged?

JM: I really made it and forced myself to drink it.

MM: Is it a magic, secret recipe, or something you just found online?

JM: It is a common indigenous drink in the Amazon and some other parts of South America. There is nothing unusual about it. It’s basically fermented manioc or yuca, a local moonshine. The only extraordinary thing is its preparation: chewing and spitting. In order to cause the fermentation process, it’s necessary to mix the cooked manioc with human saliva.

MM: Is this why you eat this thing, chew it, then spit it out?

JM: Yes. I’ve been fascinated by the repulsiveness of this culinary practice. I’ve seen the whole process of making chicha de yuca in some documentaries. Even Werner Herzog refers to it in one of his films. What is also curious about yuca root is the fact that it’s poisonous before it is cooked, so there is that strange element of danger.

MM: And then Beuys appeared to you, as if in relation to his work I Love America and America Loves Me. Even your dog is present, almost acting for the missing coyote. However, the Native American connection is not that obvious to me in the appearance of the second artist Hugo Ball.

JM: There is no direct, straightforward connection. Well, perhaps the fact that the Dadaists incorporated a lot of elements from non-Western cultures.

MM: Why did you title this video This project is not going to stop the war?

JM: Around the time when The New York Times published this frightening article about the possible bombing of Iran I had a conversation with the friend in the video who plays the roles of Ball and Beuys. We talked about the artist’s responsibility to engage in political activism. Normally, I’m convinced it’s a very individual, very personal choice and I’m against lynching artists who prefer to paint naked ladies or flowers instead of solving the problems of the world. But on that particular day I felt guilty, I felt that it was pretty indulgent of me to spend my time mastering a recipe for Amazonian moonshine, yet at the same time I felt that art is inherently pretty powerless.

JM: Around the time when The New York Times published this frightening article about the possible bombing of Iran I had a conversation with the friend in the video who plays the roles of Ball and Beuys. We talked about the artist’s responsibility to engage in political activism. Normally, I’m convinced it’s a very individual, very personal choice and I’m against lynching artists who prefer to paint naked ladies or flowers instead of solving the problems of the world. But on that particular day I felt guilty, I felt that it was pretty indulgent of me to spend my time mastering a recipe for Amazonian moonshine, yet at the same time I felt that art is inherently pretty powerless.

MM: Were you disappointed that the work actually did not stop the war, metaphorically speaking? No one apart from the art critics reviewing the Biennale took up the topic of Peltier? That it did not cause any reaction on the socio-political site?

JM: I was sincerely hoping that something good may come out of it for him.

MM: What was the reaction from the Leonard Pelteir Defense Offense Committee? They took part in the performance.

JM: This was also a rather organic process. People engaged directly in his case are really focused on getting him out of prison. They are political activists for whom a museum is presumably a bit of an unnecessary luxury; it’s off their radar. The whole idea started with a catalogue. Basically, the curators at the museum asked me to prepare a contribution for the catalogue many months in advance. They said that this does not have to be the work that is going to be shown in the Biennale, it could be anything. So this is a personal story again: I was driving from Canada back to New York, and I think I drove through several territories that were autonomous Native American territories and reservations. It was an interesting experience for me to see how the United States is all layered with these strange, separate entities inside of the whole country. And I was thinking, I wanted to establish something similar, this kind of weirdly neutral land in my catalogue pages. So the starting point was to donate my pages to Peltier. In the beginning, I did not think that I also wanted to bring in his paintings. But this collaboration with the people was wonderful, but for them the grand Whitney Biennial was a completely irrelevant event for their struggle. They were hoping for some kind of sale to fund their activities and I was hoping that the museum would offer to buy the work, but they did not.

MM: Your actions for the Whitney were strongly political: allowing for a Native American to be exhibited in a space he would never be invited to. But at the same time, you do not consider yourself to be a political artist. If Artur ?mijewski was to ask you to define yourself for the sake of his Biennial…

JM: I trust the idea that every artist is political, no matter what you do. Even if you are completely indifferent. I am a little bit scared to speak with such a high moral imperative because such attitude requires being a model citizen, and I am not. I believe that instead of telling people what to do, maybe it is better to actually do something. My involvement in politics is reflected in my life outside of art: I vote. I work for example with a group of homeless alcoholics and get them involved in making art projects.

MM: You were born in Poland, and lived there for almost 20 years. You speak Polish as your first language. You have been based in New York for over 15 years now, and was invited to participate in the Whitney Biennale of American Art. Before you worked on Native American issues, in a few of your pieces you touched upon Polish issues in the U.S., collaborating with Polish alcoholics from Greenpoint or impersonating a Polish cleaning lady in exchange for private lessons in philosophy from local intellectuals.

JM: I think it took me a long time to realize I can work with issues relating to American culture. And now again, I think maybe I can’t. I heard that my gallery had a lot of comments from people who asked, “Why is she doing this?” This is a tricky situation, and makes me think maybe I am not entitled to address such issues. But I am interested. I recently watched this interesting conversation with Joan Jonas, who did this wonderful piece The Shape, The Scent, The Feel of Things. This was based on the diaries of Aby Warburg who visited the Hopi Indian territory in the 1890s. Jonas went to the region and wanted to translate her experience into her work, but she felt that she couldn’t draw directly from the American Indian culture. She said she had felt that these people experienced so much pain, so much injustice, so much was taken away from them, that she simply couldn’t from an ethical standpoint.

MM: Do you think that this makes a difference, being a Polish artist, and therefore not being able to draw on the legacy of Native Americans?

JM: Poland is very homogenous and xenophobic, and who knows what else. Of course, I am from the outside, so maybe I am not directly involved. But from a certain point of view I could be seen as a privileged white European woman.

MM: You not only translate experiences, you also translate forms. You created this piece from feathers that was based on Hans Arp’s work, but you crafted it in a way that was specific to the indigenous peoples of the Amazon. Similarly, for the Whitney Biennale piece, with its mammoth tusks, it seemed as if you were translating Western modernist forms into a different, non-Western medium, as if they had been created by the Inuit.

JM: Ironically, I had more fun producing these particular pieces than anything ever before – this meditative, slow process connecting feathers of various colors, and with reference to those very resonant traditions.

MM: You have had some very direct contact with the Inuit people. You made this documentary about an Inuit singer, who called himself the Arctic Elvis.

JM: Unfortunately he passed away. This story is really sad.

MM: How did you find out about him?

JM: I met him when I was doing this project with the boom box in the snow for In Search of the Miraculous, Continued… Part 2.” I met him in Iqaluit, the capital of Nunavut Territory. I was amazed by him, so I decided I needed to come back a few months to talk to him more.

MM: In the film he seems so happy, that finally he has found somebody to tell his story to, and perform in front of the camera.

JM: Yes, he definitely was excited about it, and I was also excited about it. It was a very symbiotic relationship. But actually, I was thinking of the film Nanook of the North because I would like to make a project about this. I have this crazy idea to watch this movie together with this woman who is called Pema Chodron. She is originally a New Yorker who became a really big authority on Tibetan Buddhism. She is one of the highest spiritual leaders, and she is fantastic. It is my dream to watch this film with her.

MM: In order to hear her comments?

JM: It would be cool to even watch this with her in silence. She speaks a lot about forgiveness. I am reaching a very difficult topic, maybe I am shooting myself in the foot by speaking about it. I am interested in gaining some kind of forgiveness for the crimes of colonialism. Chodron is a very interesting person to listen to; her teachings are so open. I like this kind of convoluted situation because this is, again, a white person who became an authority in a religion that comes from the non-Western world, and she devoted her life to studying mindfulness and forgiveness. So it interests me, this passive act of watching this film with her. Nanook of the North, regardless of the political incorrectness of its making – basically a staged white folk fantasy about the exotic guys who live up in the North — is also what Buddhism aspires to. It is a fantasy about the simplicity of life; living close to nature. So I like all of the subtexts this action could involve.

MM: Weren’t we speaking about your works with the Polish alcoholics? In the collective show Knight’s Move that took place at the Sculpture Center in New York in 2010, you showed two pieces that linked your fascination with the community of Polish alcoholics and magical rituals. In the Mists is a video of the Virgin Mary walking through the park in Greenpoint and blessing the alcoholics. The second piece, In Search of Primordial Matter, contained a washing machine filled with various objects that supposedly, in some cultures, possess magical powers.

MM: Weren’t we speaking about your works with the Polish alcoholics? In the collective show Knight’s Move that took place at the Sculpture Center in New York in 2010, you showed two pieces that linked your fascination with the community of Polish alcoholics and magical rituals. In the Mists is a video of the Virgin Mary walking through the park in Greenpoint and blessing the alcoholics. The second piece, In Search of Primordial Matter, contained a washing machine filled with various objects that supposedly, in some cultures, possess magical powers.

JM: They were being “accelerated.” This was referring to the famous Large Hadron Collider in Geneva, and the Higgs particle. I was hoping to cause a collision with these magical objects.

MM: Was there any collision? I always wonder with those pieces where the viewer can’t be sure if the thing is really there, like with Manzoni’s cans of shit. I was wondering whether you really placed these objects in the washing machine, the way they appear on the accompanying “laundry list.” I do remember the sound; one could tell that there really was something in there that was spinning.

JM: I did put these objects into the washing machine, but some of them were hardly tangible. For instance, on the list there was a repetition of Zbigniew Warpechowski’s performance and things like “a handful of darkness.” There was also a reference to Beuys because there was a hare that knows a lot about art.

MM: Did you really put a hare inside?

JM: I put a taxidermied hare into the machine and convinced myself that he knew a lot about art.

MM: So when you opened the washing machine, a month or so into the show, did anything happen?

JM: Well, who knows what happened? It is a tricky thing. One can believe in the theory that the flapping of the wings of a butterfly in China can cause a hurricane in another hemisphere. Who knows?

MM: You play a lot on this idea of objects being totems, possessing secret powers, or some kind of magic. Do you really believe that they do? Or is it more an investigation into various beliefs that don’t seem rational?

JM: I want to give things the benefit of doubt. It’s a complicated matter — magical thinking, I guess. I wouldn’t call myself a person who firmly beliefs that objects possess some special powers. But on the other hand, it seems there is some nostalgia even in the recent currents in the art world – like this recent show on animism by Anselm Franke. I read a bit about Graham Herman’s theory of the autonomous existence of objects. He is this contemporary theorist who tries to bring back the idea that matter has power to it, not just us humans. I feel I almost need to sign up for courses in philosophy, for now I navigate this territory mostly intuitively. But I am trying to do this with humor; it is not that I am deadly serious about everything. Of course, again, it goes back to anthropology and ethnography, and studying different cultures and different beliefs. Plus coming from Poland, I feel inherently prone to analyzing things from the perspective of a believer, whether I am one or not.

MM: You also recreate these objects. You paint on the skins of animals, and you embed things with feathers. You create these things that relate to traditional crafts.

JM: A little bit. Although I feel this is still something I am testing. I think the way I work is that I take risks and I experiment with things that might be ridiculous. I do not know if I should admit it, but I always have this soft spot for the aesthetics of non-Western cultures. I am just crazy about those beautiful textiles from Peru, for example.

MM: What risks are you taking right now?

JM: I am not sure if I am taking any risks right now. I was recently invited to an exhibition that takes place in this pristine archipelago in Norway, where nobody lives, and there are no trees and no plants; there is only minimal vegetation, and the islands are tiny. Every artist invited gets one island to produce a project. There are a lot of constraints regarding materials, because you cannot do a lot, for example, you cannot drill or otherwise permanently change the environment. It is a very temporary exhibition that takes place over a weekend. I felt very moved that I was invited to this exhibition. I always enjoy presenting my work among a group of people with whose work I relate strongly. They contacted me out of the blue and I already loved the title: Five Thousand Generations of Birds. For that show I decided to hire a local baritone to sing through a big megaphone. I want this person to sing songs by Franz Schubert, and maybe Schumann. I picked songs that are related to nature because there were a lot of them in the Romantic 19th-century repertoire. They are full of allegories, but instead of bringing us closer to nature I feel like they point to the fact that we are completely disconnected from that nature. We create those beautiful words, but they cannot exist without us, and nature doesn’t give a damn about our beautiful words. It is like speaking to nobody. Also, I found this gem of a song about a travel to distant land, where they describe Lap people or the Inuit as ugly, smelling of fish, and making squeaky sounds. I think some of this 19th-century racism adds an interesting touch. I think maybe here I can redeem myself for my “exploitations” of the non-Western cultures, and admit the fault of European males.

MM: Are you planning to return to the Polish topic at all?

JM: No, I would like to, but who knows. Right now I am thinking of getting into another strange subject matter. It is my dream to make a project with Imre Kertesz. I want to make a wax cast of him. I am about to write a letter to his wife, and I am afraid she will say no. He lives in Berlin, and I’ve been told he is in a rather frail state.

MM: You want to cast his face or his whole body?

JM: The whole body, sitting on a chair. This is not a political statement; it’s more personal. I find his book The Kaddish for the Child Unborn very compelling. Since I read it I have been obsessed with the idea of preserving some kind of tactile form of Kertesz. What I always found fascinating about him was this strange sense of peace, almost a weird form of enlightenment similar to Buddhism. When you endure so much, you become at peace with the world and you can explain it like nobody else can.

MM: Would you use plaster?

JM: I am not sure if it would be in plaster; there are more contemporary materials. I would also like to convince Robert Morris to finish his collaboration with Beuys that they had many years ago, an action/happening simultaneously at two different ends of the Atlantic. Beuys performed his part in Germany, but Morris did not do his part in the United States. So I want to convince Morris to do this now.

MM: Why did Morris not complete the piece? What is the story?

JM: There are different versions circulating. Some people claim that he did do it, but someone apparently asked him, and he said he did not. So I imagine this is a story about happenings in two different universes. There is this idea from Einstein’s relativity theory about twins who age at slightly different speeds. So I wanted to do this, a bit like Stanley Kubrick: a Morris piece that was supposed to happen thirty years ago happens now, as a result of being affected by “another element,” that is myself I am interested in the sheer poetry of Morris, who is an elderly man right now, wrapping himself in felt and performing something that he first agreed to—and then refused to do—many years ago.

MM: That’s a beautiful idea. Thank you for the conversation.

JM: Thank you.

Magdalena Moskalewicz is a Polish art historian and art critic based in New York City, where she works as a Mellon C-MAP Fellow at the Museum of Modern Art, focusing on postwar art from Central and Eastern Europe. Magdalena holds a Ph.D. in art history from Adam Mickiewicz University in Pozna? for her research on the modes of transgressing the painterly medium in Poland in the 1960s. She has published extensively on art from the People’s Republic of Poland, as well as post-1989, in various books, exhibition catalogues, and journals. Prior to her moving to New York in April 2012 she was the editor-in-chief of Arteon, a monthly magazine on contemporary art.

Magdalena Moskalewicz is a Polish art historian and art critic based in New York City, where she works as a Mellon C-MAP Fellow at the Museum of Modern Art, focusing on postwar art from Central and Eastern Europe. Magdalena holds a Ph.D. in art history from Adam Mickiewicz University in Pozna? for her research on the modes of transgressing the painterly medium in Poland in the 1960s. She has published extensively on art from the People’s Republic of Poland, as well as post-1989, in various books, exhibition catalogues, and journals. Prior to her moving to New York in April 2012 she was the editor-in-chief of Arteon, a monthly magazine on contemporary art.