Interview with Jelena Vesić About her Show Political Practices of (post-) Yugoslav Art: Retrospective 01

In this interview we discuss the exhibition Political Practices of (Post-)Yugoslav Art: RETROSPECTIVE 01 (hereinafter referred to as PPYUart that Jelena Vesi? co-curated with a group of independent curators, theorists, researchers, artists and activists, andwhich was presented at the Museum of Yugoslav History in Belgrade in 2009. The project was initiated by four independent organizations: the new media center kuda.org (Novi Sad); the curatorial collective WHW (Zagreb); Prelom kolektiv (Belgrade); and SCCA/pro.ba (Sarajevo).

Nikola Dedić/Aneta Stojni?/ARTMargins Online: I would like to start with a question about the exhibition title, which is long and difficult to remember on the one hand, but also very precise and “mathematical” on the other. Can you tell us a few words about the title?

Jelena Vesi?: The title contains in itself a certain kind of mathematical-linguistic-ideological formula, which can be broken down into its constitutive parts, and thus put into a relations with each other.

1. The first part can be the notion of Political Practices of Art, which is used here in two directions: in the sense of making political art, that is, relation of art production in the realm of realpolitik, and in the sense of making art politically, that is, interests in reflection of collaborative interpretative and other circumstances of production and reception of art, including interests in the form.

2. The second part can be the notion of Yugoslavia, which is also used in a twofold manner. On the one hand, it is realpolitical metaphor that signifies certain revolutionary and anti-fascist politics that can be named as Yugoslavia. On the other hand, the title represents a concrete, historical, chronological and geo-political category. Historically speaking, speaking, we concentrated mostly on the period between 1941-1980, when the overture for the dissolution of the country already started.

3. The third part can be the prefix “post,” presented in brackets as it alludes to the “post-socialist condition as ideology”, an ideology that is deeply inscribed in the contemporary understanding of art and culture in the former real-socialist countries. The ideological phenomenon of the “post-socialist condition” is extensively elaborated in Boris Buden’s essay “Two Left Shoes in the Museum of Communism” and in Pastko Mo?nik’s fND/AMOus text “The East.”

4. Finally, the fourth part of the title is the notion of the “retrospective”, which in our case meant a sketch for a new historical perspective.

ND/AS/AMO: What methodological approach did you take with PPYUart, especially in terms of working collectively?

ND/AS/AMO: What methodological approach did you take with PPYUart, especially in terms of working collectively?

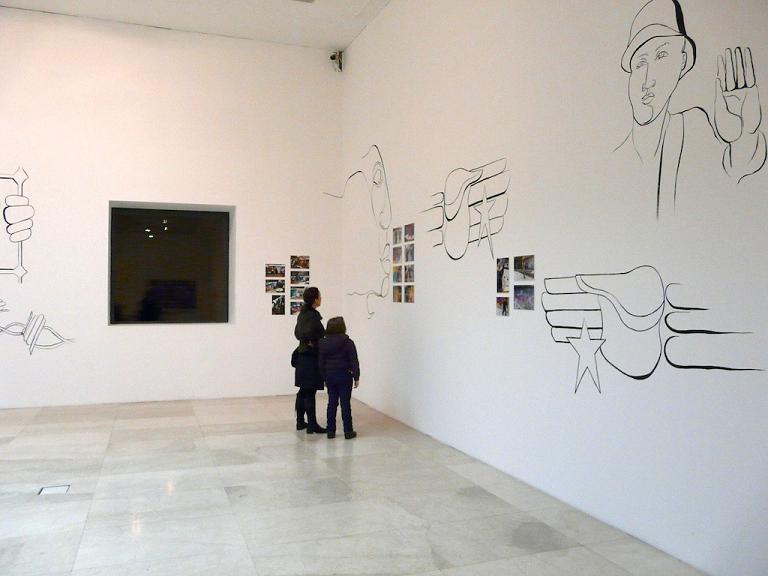

JV: It is important to point out that the concept of the retrospective developed as an open collective form, as opposed to the closed, individualist form of the traditional museum retrospective. The exhibition was developed as a network of autonomous investigative units (nine exhibiting sections and six art works), which at the same time expressed and marked the process of networking and the immediate cooperation of all protagonists towards formulating a collective statement in the form of an exhibition. I would like to mention here all the exhibiting sections of PPYUart:Retrospective 01 – their titles sometimes directly recall their contents – but also the people who created these sections and their interpretative contexts.

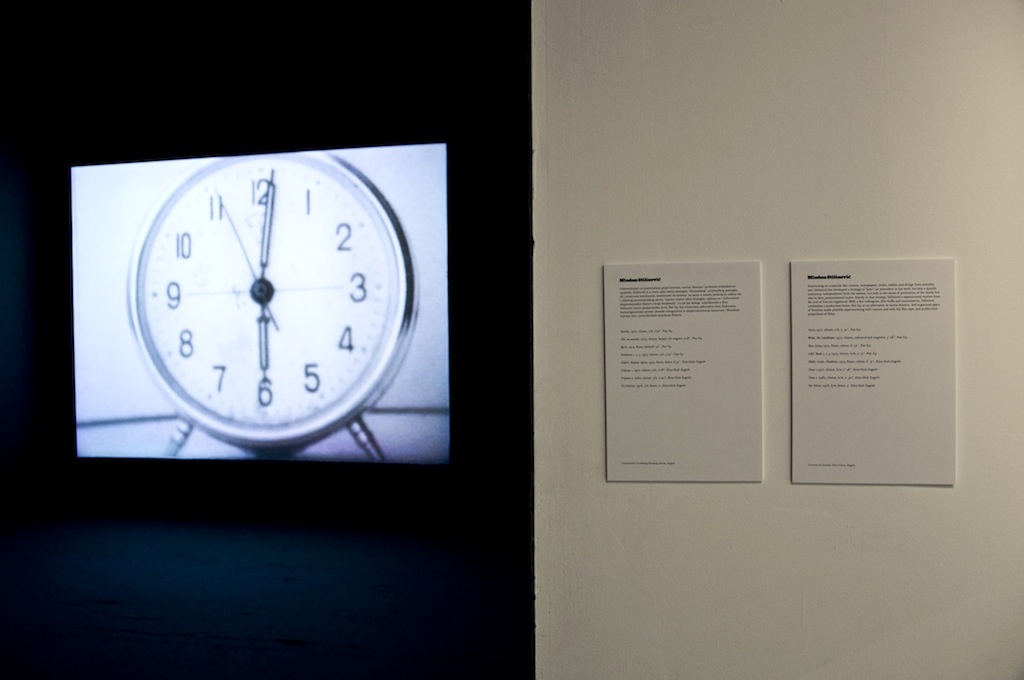

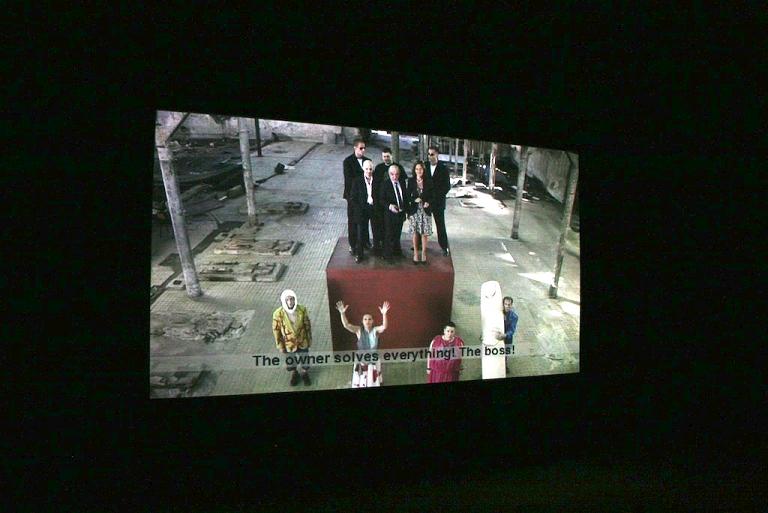

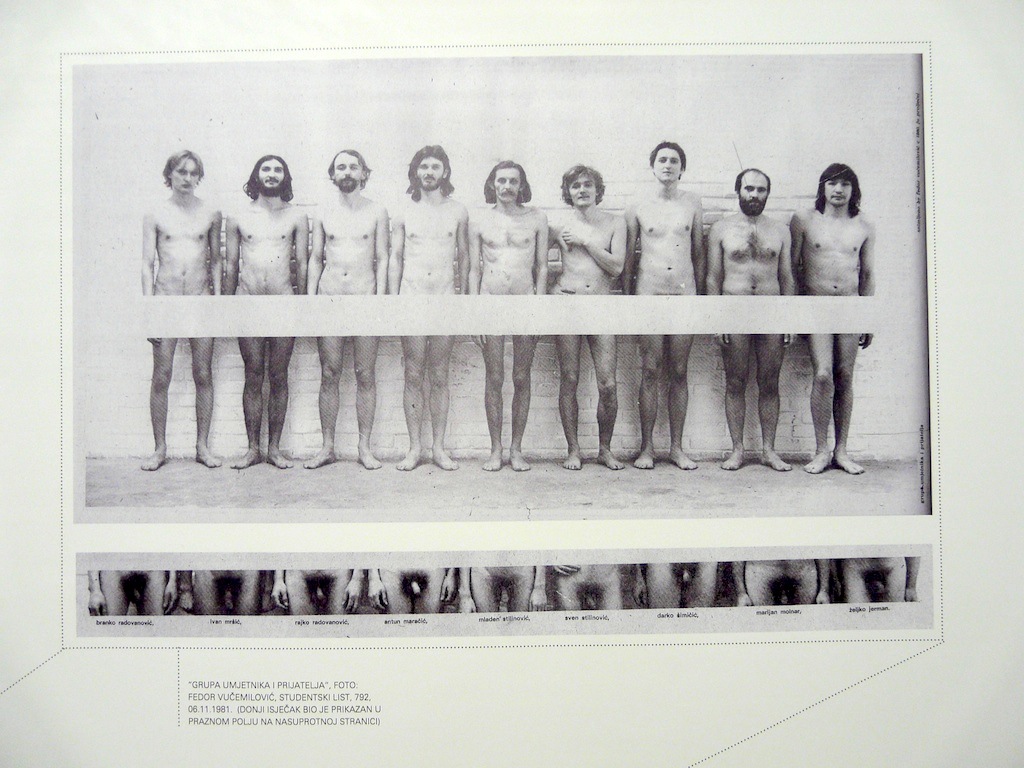

The sectional titles are: How to Think Partisan Art? (Miklavž Komelj, Lidija Radojevi?, Tanja Velagi?, Jože Barši); Didactic Exhibition (WHW), Vojin Baki? (WHW); As Soon as I Open My Eyes I See a Film (Ana Janevski); TV Gallery (SCCA/pro.ba, kuda.org, WHW); The Continuous Arts Class (kuda.org); Removed from the Crowd: Dissociative Association (DeLVe); Two Times of One Wall: The Case of the Student Cultural Centre in the 1970s (Prelom kolektiv); and Kunsthistorisches Mausoleum. Apart from this the exhibition presented a group of contemporary art works that correspond thematically and methodologically to the above mentioned sections: Retired Form by David Maljkovi?; Journal No.1 — An Artist’s Impression by Hito Steyerl; On Solidarity by Darinka Pop-Miti?; Black Peristyle by Igor Grubić; Partisan Songspiel. Belgrade Story by Chto Delat (in collaboration with Rena Raedle and Vladan Jeremi?); and The Path of Remembrance and Comradeship by Tanja Lažeti? and Dejan Habicht.

My role was to curate the retrospective exhibition, but unlike authorial/authoritative/individualist forms of curatorship, PPYUart was curated on behalf of and for our newly established collective, much like Vladimir Tatlin writes of the dialectical form as “initiative individual in the creativity of the collective” (in a text of the same title from 1919). Our common starting point with the PPYUart retrospective exhibition was an attitude that countered the dominant, one might also say canonical, historical representations of Yugoslav art and culture, as well as the historical and cultural-political status of contemporary art under the general circumstances of peripheral neoliberalism.

ND/AS/AMO: Within the PPYUart exhibition you reflect on the politics of the kind of historicization that creates our contemporaneity. How do you see the significance of this approach in terms of re-interpreting the representations of (post) Yugoslav art in the local and international context?

ND/AS/AMO: Within the PPYUart exhibition you reflect on the politics of the kind of historicization that creates our contemporaneity. How do you see the significance of this approach in terms of re-interpreting the representations of (post) Yugoslav art in the local and international context?

JV: Within the framework of the reigning discourse of today that follows the development of “regional” art histories, the representation of the art of Socialist Yugoslavia is articulated in two different, yet interconnected ways. On the one hand, on the global level, it is presented as a part of something that could be called the dissident art of Eastern Europe, a narrative of brave artists that function as the voices of a rebellion against “the totalitarian Communist system” – fighters for the basic human right of individuals to freedom of expression. On the other hand, on the local level, Yugoslav art is fragmented and (re)arranged into a sequence of national art histories that are based on the “liberation” of individual artistic contributions from the “Communist yoke” and their “return” under the aegis of a native national culture. This makes an integral part of the process consolidating the newly established nation-states a process lasting from the wars of the 1990’s onwards. Such frameworks and interpretations of the past establish ideological narratives that are projective in relation to the concept of “contemporary art;” in other words, they frame the historical reality in relation to which contemporaneity is to be produced and into which it has to fit. What we have here are narrativizations of the past which, in a broader social sense, actually serve the purpose of strengthening the dominant anti-Communist consensus, even uniting seemingly opposed political views such as pro-European democracy and ethno-nationalism.

In that sense, the exhibition PPYUart was an invitation to investigate, or at least to question the dominant notions of Yugoslav art, culture and social-political system. The exhibition didnot represent a well-rounded historical overview of the cultural and social life of our former common state, nor was it a partial archive of some artistic movements and practices that up to now have been insufficiently historicized; rather, its aim was primarily (self-) educational, in the sense of setting up models for independent research into lesser known histories that could give us a different perspective for positioning and acting within the framework of today’s situation.

Of course, whenever we speak about the past, the issue of nostalgia comes up. Svetlana Boym nicely defined the phenomenon of nostalgia as “history without guilt,” and I must also say here that the exhibition PPYUart, is firmly opposed to that what is today called Yugo-nostalgia, a kind of return to the “good old times.” Although the material basis of the current nostalgia for socialist times is still the living memory of the period when the majority of the local population enjoyed a better standard of living and considerable social welfare, Yugo-nostalgia fits perfectly into today’s model of cultural industries. From Yugo-nostalgia, socialism presents an image of a consumerist paradise, spiced with ideological totalitarianism and an exotic life. In a certain way, we can also read in this image that its imminent realization is promised by the advent of neo-liberalism, and this is precisely the kind of future PPYUart critically presented.

ND/AS/AMO: You often speak about a conceptual approach to exhibition making, which means something more than just “exhibition” in its final form. How do you see the interventionist potential of exhibition practices in this particular case?

ND/AS/AMO: You often speak about a conceptual approach to exhibition making, which means something more than just “exhibition” in its final form. How do you see the interventionist potential of exhibition practices in this particular case?

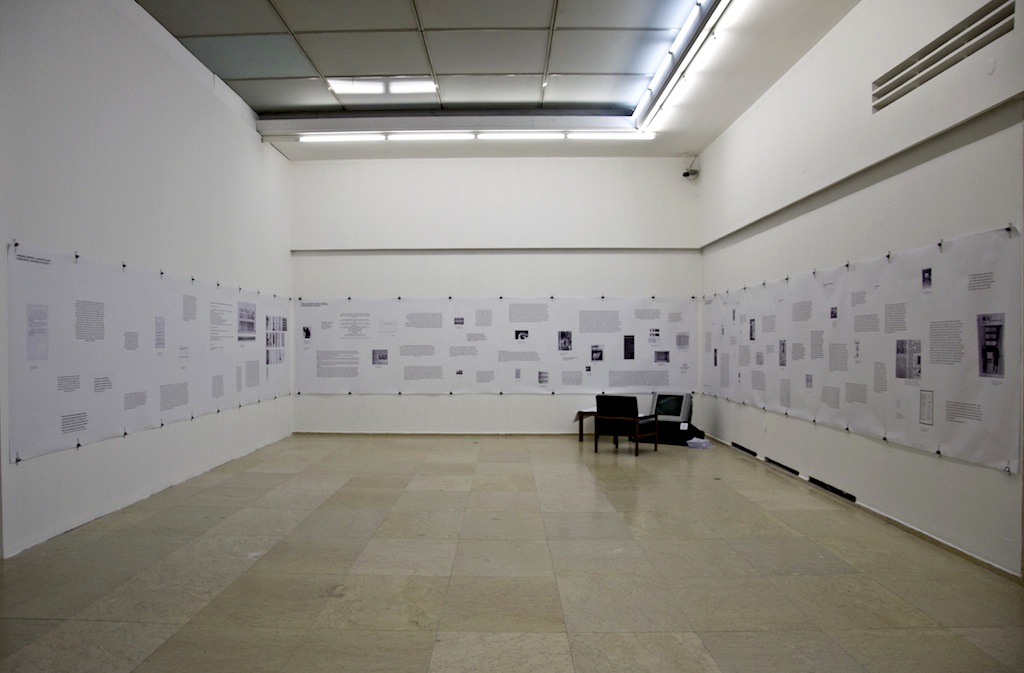

JV: I see the potential of PPYUart in the fact that its internal narrative was the politics of historicization itself. That is, history or the history of art was presented as the exhibition’s material and the material for artistic work. The display was made up not of artworks (in the narrow sense of the word) or “curatorial pieces,” but of historical narratives – that is to say, of the critique of hegemonial historical narratives.

When Griselda Pollock spoke of a critique of the historical-artistic canon, she formulated it from her own feminist perspective, and through the concept of intervention, or a “lateral approach” to something we might call an institutional reproduction of the authority and the truth of art history. According to this interpretation, an intervention represents an act which “comes from the inside,” from one part of the whole, and which, in the context of contemporary culture, points to the structural problems of academic disciplines and exhibition politics, and their connections with the material and social practices that surround us. Griselda Pollock also made another important point: even when an intervention speaks the language of a minority, of the local or the particular, its effects are universal. In other words, it can be said that an intervention is not characterized by “filling in empty spaces,” or by “supplementing history” with something that was previously left out, missed, or which is less well known. Rather, an intervention is characterized by questioning, pointing to, and naming the canon; that is, by something that is omnipresent in the narration, evaluation and categorization of artistic activities.

In this context, the exhibition PPYUart with its use of contemporary art exhibition (rather than academic) discourse could also be described as a critique of the dominant politics of historicizing theYugoslav past. The exhibition is a “concise form of speech” in relation, for example, to studio and academic writing, and it is here used as a medium and a means of intervention within the framework of the canon of art history. It is precisely this immediacy of appearance afforded by the medium of exhibition (again, in relation to the duration and process-character of art-historical work) that we could describe as the spatial-temporal characteristic of the exhibition discourse, a characteristic furthermore that enables a condensed counter-attitude towards the “entirety” of art history. Certainly what we are talking about here are geopolitical readings of peripheral art histories that have been the focus of critical examination for the past two decades.

PPYUart emphasizes a radical, subjectivist and subjectivizing reading that approaches history as a “sphere of struggle” and is closely related to Benjamin’s concept of “historicity as actualization”.

ND/AS/AMO: The specificity of the exhibition of PPYUart is that it establishes and reviews three historical references, or three forms of critical thinking in the sphere of art, as developed within the framework of Socialist Yugoslavia, also known as a precursor of the actual political concept of Yugoslavia: “Partisan Art;” “Socialist Modernism;” and “New artistic Practices.” Can you tell us more about the choice of these specific references?

JV: The concepts of Partisan Art; Socialist Modernism; and New Artistic Practices are presented as historical references that we may take into consideration as relevant for today’s conceptualization of politics within the sphere of contemporary art. These references are used both in the thematic sections of the exhibition and in individual art works, and in a manner in which they have not been used until now, and which is not to be “expected” within the framework of the established “canons of historicization.”

The term “Partisan Art” points to the historical example of uniting art and social-political engagement in a joint gesture. It is a new historiographic notion that appears within in the “vacant space” of socialist realism. Partisan Art assumes positions contrary to the visions of artistic activity within an autonomous cultural sphere, and it is close to the avant-gardist concept of art as a revolutionary vanguard. What we are dealing with here are certainly not majestic images of the struggle of the partisan forces, as in the dominant ideological representations of the Yugoslav socialist state. What is at stake is rather a questioning of the relationship between politics and art, conceived through the simultaneity of art and resistance, action and thought, or the ability to think outside the boundaries of the existing social rationality.

Socialist modernism refers to a set of strategies, approaches and statuses of art that we encounter in the historical heritage of modernism. Its problems, conflicts, potentialities, and limitations are explored within the framework of Socialist modernism. Socialist modernism once represented a kind of a “trademark” of the specific nature of the Yugoslav state’s cultural policy, and the specific character of its socialist path, as opposed to the cultural policies within the Warsaw Pact in relation to the Western concept of modernism. The specific character of this artistic concept lies in its affirmation of the possibility of joining the political sphere and the language of art. Whereas in accordance with the general modernist viewpoint, the politics of art lies in its language, Socialist modernism paradoxically represents the adoption of the autonomy of art on the level of a state concept of Socialist Yugoslavia. It also points to the possibility of the abstract language of art becoming an exponent of official ideology. The term Socialist modernism, which has also been referred to as “Socialist aestheticism,” has often been interpreted as a form of neutralizing the language of art for the purposes of distinguishing the cultural policies of Socialist Yugoslavia from the propagandist methods of the USSR and the doctrine of socialist realism; it has also been seen as blocking the critical potentials of art that would eventually disclose the problems of a bureaucratized state system of culture and its reactionary effects.

In the course of the past several decades, not only in the local context but also on the international art scene, the modernist heritage and the entire artistic project of modernism has been revisited over and over. Many of these revisions were based on the retro-fashion of “new formalism” and the general “nostalgia for the 20th century” as a time of social projects and political events that have now disappeared over the horizon of “contemporaneity.” In this light, the exhibition PPYUart, by dealing with the politics of Socialist modernism, critiques the ideological and institutional constellations that have produced these nostalgic and romanticized images of the past. Exploring the practical manifestations and particular situations of the modernist heritage in Socialist Yugoslavia, PPYUart tried to single out progressive ideas based on the proximity of the universalism of modern art, on the one hand, and the universalism of social emancipation, on the other.

Finally, the term New Artistic Practice was established, in historical terms, through a global reading of conceptual art and formulated by art critics who were active in Yugoslavia in the 1970s. The term served as an intervention within the modernist paradigm of the “autonomy of art,” and as a radical turn in the sphere of artistic production. This radical turn presupposed shifting the mimetic function of art from the sphere of “representation” to the very ideological apparatus that establishes the criteria of evaluating art. In Yugoslavia, the New Artistic Practices made two fundamental contributions that are examined even today. One is a demystification of the process of artistic production that presented artistic work as a process, that is to say, as an open experiment, and not necessarily as a product. The other concerns the democratization of artistic practices, based on the gesture of “opening the code” of artistic production and presenting the actual artistic act as something that is accessible and possible for everyone rather than being closed up within the form of a stable art work understood as an exclusive object. It is a critical and political turn in art that is based on the dialectics of “first-person discourse” and self-organized collectivist action. Within this context, the project PPYUart laid the emphasis on questioning the “utopian projections” and “contemporary institutional assimilations” of the new artistic paradigm of the 1970s in the sphere of contemporary art.

Finally, the term New Artistic Practice was established, in historical terms, through a global reading of conceptual art and formulated by art critics who were active in Yugoslavia in the 1970s. The term served as an intervention within the modernist paradigm of the “autonomy of art,” and as a radical turn in the sphere of artistic production. This radical turn presupposed shifting the mimetic function of art from the sphere of “representation” to the very ideological apparatus that establishes the criteria of evaluating art. In Yugoslavia, the New Artistic Practices made two fundamental contributions that are examined even today. One is a demystification of the process of artistic production that presented artistic work as a process, that is to say, as an open experiment, and not necessarily as a product. The other concerns the democratization of artistic practices, based on the gesture of “opening the code” of artistic production and presenting the actual artistic act as something that is accessible and possible for everyone rather than being closed up within the form of a stable art work understood as an exclusive object. It is a critical and political turn in art that is based on the dialectics of “first-person discourse” and self-organized collectivist action. Within this context, the project PPYUart laid the emphasis on questioning the “utopian projections” and “contemporary institutional assimilations” of the new artistic paradigm of the 1970s in the sphere of contemporary art.

ND/AS/AMO: We have spoken about the relationship between the exhibition PPYUart and the art-historical canon; however, we might also see the show as a critique of the canon as an authoritative point of reference within the field of exhibition making. How would you describe canonical curatorial practices?

JV: Canonical curatorial practices can be described by means of a certain chain of relations: institution/artists; theorists/organizers/technicians/sponsors/the media, etc. In this series the curator features as the moving spirit of the production, and his/her authorship consists in setting the “production line” inmotion. The way a bicycle chain enables the movement of wheels by engaging each cog of the cogwheel, a curator must engage each production. He/she must be connected to each and every one of them. The result of such a process of production is an organized and constructed exhibition space (an institutional space); a completed and designed relationship between objects and subjects (a restrictive, fixed relationship); and various animation practices (guided tours of an exhibition, programs for children, exclusive appearances of the artists, etc.).

In curating practice so far, the critique of canonical exhibition canons has been carried out mainly through formal “games” that violated, in one way or another, the established “chain of relations” in the production of an exhibition: violation of the unique authorial position of the curator (for example, within the framework of successive selection models: the selected becomes the selector in the next round); the exhibition as a sum total of various curatorial narratives (fragmentation of the common narrative of the exhibition); “opening the code” of art production (presenting ideas and sketches instead of finished works); an archival approach to the exhibition (presenting a large quantity of material from which the observer selects what s/he wants to view, thus creating his/her own version of the exhibition); taking the exhibition out into the street or some other “non-artistic space;” artists become curators and vice versa, etc.

However, the most radical critique of the curatorial canon would have to break the curator’s position as the moving spirit of production at the center of the institutional apparatus. This might concern the practice of maintaining museum programs, matching exhibitions, launching new generations of artists / new topics and maintaining the flow and rhythm of cultural production as such , all of which leaving us with the impression that things are “in order” and that everyone should remain “in his/her place.” A critique of the curatorial canon would thus, first of all, be a critique of the meeting place; of the facile attractiveness of current theory and current artistic production within an accessible curatorial synthesis presented in the form of a monumental exhibition. It would be primarily a critique of the view of the curator as a manager, as someone who manages things, who maintains a decent flow of the production and who fills all the roles and agencies that this mediating position affords him/her. Additionally, a critique of the curatorial canon would be a critique of overproduction, of facile, intriguing topics serving to entertain the culturized layers of society.

Finally, the critique of the curatorial canon would be a critique of the syntagm of “curating art,” as proposed by Peter Osborne (Manifesta Journal No 7). “Curating art” for Osborne is the only mode of the existence of curating. It is positioned as opposed to, towards and in connection with art in the sense of an artist or art work, and it by no means had and should not have its autonomy in terms of language, concept or form.

If one negates the existence of the language of exhibitions and the “authorship” of the curatorial gesture (this authorship should not confused with the “great curatorial names” created by the cultural industry), then we are talking about mere institutional management where curating is reduced to the function of ensuring the exhibition of art works and the unhindered development of museum programs following an established rhythm – in short, maintaining the institutional order. However, this view is not just the abolition of “authorship,” it is the abolition of a thinking position of interpretation, contextualization and referential discourse. If curating survives only within the syntagma of what Osborn calls “curating art,” then the curator is only an invisible servant ormanagerial representative of the art scene and its professional cultural institutions.

The exhibition PPYUart could serve as a good example of the relativization of this view, since it shows that curators, theorists and artists may be gathered together to pursue the “hidden task” of staging an exhibition, and that they may use the exhibition as a form in a manner that is different from the institutional differentiation of various positions, the professional division of work, and the assignment of fixed social roles.

- Focus Issue on Serbian Art in the 2000s

- Interview with Miško Šuvakovi? about Art in Serbia in the East European Context

- Interview with Nikola Dedić

- Interview with Ana Vujanovi?

- Interview with Aneta Stojni? About the Interdisciplinarity of the Arts

.jpg) Jelena Vesi? is an independent curator, cultural activist, art critic and editor. She was a co-editor of Prelom, Journal of Images and Politics (Belgrade 2001-2009), and founding member of Prelom Collective (Belgrade 2005-2010; http://www.prelomkolektiv.org/). She is co-editor of Red Thread – Journal for Social Theory, Contemporary Art and Activism since 2009 http://www.red-thread.org/

Jelena Vesi? is an independent curator, cultural activist, art critic and editor. She was a co-editor of Prelom, Journal of Images and Politics (Belgrade 2001-2009), and founding member of Prelom Collective (Belgrade 2005-2010; http://www.prelomkolektiv.org/). She is co-editor of Red Thread – Journal for Social Theory, Contemporary Art and Activism since 2009 http://www.red-thread.org/