GoEast: The 12th Festival of Central and East European Film in Wiesbaden

GoEast: The 12th Festival of Central and East European Film in Wiesbaden, held in April 2012, devoted its symposium section to a thorough and scintillating reevaluation of Lenfilm, entitled: RealAvantGarde – With Lenfilm Through the Short 20th Century.

About the Lenfilm Studio

Jeremy Hicks

Lenfilm, the first Soviet studio to be founded after the revolution, but perpetually the second studio of the USSR exerted enormous influence at crucial periods of Soviet and Russian film history: from its contribution to the 1920s avant-garde with the FEKS films and innovative animation, to its era-defining Chapaev and Maxim trilogy in the 1930s, through less famous, but no less crucial contributions to Thaw cinema, genre cinema, Brezhnev-era realism, concluding with a revisiting of experimentation in the Perestroika era. While the studio’s future is far from clear, GoEast: The 12th Festival of Central and East European Film in Wiesbaden, held in April 2012, devoted its Symposium section to a thorough and scintillating reevaluation of Lenfilm, entitled: RealAvantGarde – With Lenfilm Through the Short 20th Century. One of the great merits of the symposium, curated by the protean talents of Barbara Wurm and Olaf Müller, was its emphasis on the lesser known and less recognised dimensions of the Lenfilm catalogue, so that there was no screening of the FEKS films or Chapaev. Instead, there was a consistent attempt to push beyond the boundaries of the obvious to discuss neglected names or disregarded dimensions of the studio’s production. To aid this, each of the four days coupled morning lectures with afternoon and evening screenings of films discussed there. The effect was intellectually stimulating and unprecedentedly popular for the GoEast festival symposium.

2012 – The Year of Soviet Studios

Natascha Drubek

In May 2012 the Russian online journal openspace.ru published an extensive article by Ivan Chuviliaev on Soviet film studios — some of them still working, some closed down.The article by Ivan Chuviliaev, “Soviet Film Studios: Whatever became of them?” also contains clips from the film which were made in the studios http://os.colta.ru/cinema/projects/70/details/37038/?attempt=1 (14/5/2012) There is a growing need to understand the institutional aspects of Soviet cinema. This has been an important part of cinema studies in the West where the phenomenon of the American studio has been under the scrutiny of film historians for many decades. By contrast, there has been little continuous tradition of research into Soviet cinema history that focuses on the studios.

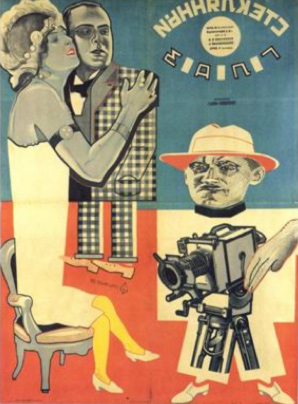

One has to be all the more gratified that in 2012 there have been several film retrospectives devoted to Soviet film studios. This started with a grand retrospective of films produced by the Mezhrabpom-Film studio at the 62th Berlinale in February.The Kinofest NYC in New York celebrated the anniversary of the Soviet Ukrainian studio VUFKU which dates from 1922. VUFKU, the most prolific Soviet film studio of the silent film era, produced cinematic milestones – Oleksandr Dovzhenko’s Arsenal (1928) and Dziga Vertov’s The Man with a Movie Camera (1929). http://www.kinofestnyc.com/history.html Entitled “The Red Dream Factory. Mezhrabpom-Film and Prometheus 1921—1936”, the festival showed 43 films produced by Mezhrabpom-Film. The studio was a joint venture set up in 1922 by Soviet producer Moisei Aleinikov and German communist Willi Münzenberg, initially called Mezhrabpom-Rus’. It produced approximately 600 films between 1922 and 1936. At the height of Stalinism it was transformed into a studio for the production of children’s films.Highly recommendable is the book accompanying the retrospective: Günter Agde, Alexander Schwarz (ed.): Die rote Traumfabrik: Meschrabpom-Film und Prometheus (1921–1936). Berlin: Bertz + Fischer 2012. http://www.bertz-fischer.de/product_info.php?cPath=1_36&products_id=374 After Berlin, the retrospective travelled to MOMA in New York: http://www.moma.org/visit/calendar/films/1264

Lenfilm, another important (and still active) studio was presented during the Lenfilm retrospective and symposium at the 12th GoEast Festival in Wiesbaden in April 2012.Tat’iana Vol’tskaia: Will Society Decide about the fate of Lenfilm? http://www.svobodanews.ru/content/article/24704454.html – 11/9/2012 This symposium made speakers and audiences realize how important the legacy of Soviet film history for Russian cinema today. The studio now has become a talking point in the Russian media.

Lenfilm, which was founded in 1918, is in debt and in danger of being closed. The land on which the studio stands is very valuable as it is in the center of St. Petersburg, not far from the Fortress of Peter and Paul. Until recently there were three groups who fought for their ideas for the future of the studio. The first group wanted to transform it into a production center (According to other sources initially this group had plans to turn the studio into something called Lenfilm-Park which would be a Disney World on the Neva). The second option, put forward by a company that planned to turn the property into a business park, was withdrawn recently. The third option would be to modernize the Lenfilm studio to the standard of a contemporary film studio, and to retrieve the rights of past Lenfilm productions lost a decade ago. This concept has been put forward by director Aleksandr Sokurov who wants to revive a specialized production profile in the studio, and add an educational center. It now seems that Sokurov and his group were not successful.

1. Gaby Babic

John Riley and Natascha Drubek interview Gaby Babic, Director of the GoEast Festival and symposium.

2. Barbara Wurm & Olaf Möller

John Riley and Natascha Drubek interview Barbara Wurm and Olaf Möller, curators of GoEast Festival and symposium.

3. Shostakovich in Film

John Riley, film scholar and author of Dmitrii Shostakovich: A Life in Film talks about Shostakovich’s approach to film music and its relation to the Lenfilm tradition. In the second part of the interview, John Riley talks about Shostakovich’s use of song in Grigorii Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg’s Alone (Odna, 1931). In the symposium, Shostakovich’s film music was represented in particular by his contributions to Mikhail Tsekhanovsky’s animated films as well as to Kozintsev and Trauberg’s more widely known The Youth of Maxim (Iunost´ Maksima, 1934).

4. The Discovery of Evgenii Cherviakov

Petr Bagrov, film historian at State University of Film and Television. St. Petersburg, and an unrivalled authority on Lenfilm, discusses the significance of the discovery of Evgenii Cherviakov’s film My Son (Moi syn, 1926) fragments of which he previewed at the symposium. Cherviakov’s Cities and Years (Goroda I Gody, 1930) was also screened at the symposium.

5. The Place of Studios and the importance of Fridrikh Ermler

Sergei Kapterev, of Moscow’s Film Research Scientific Institute and the State Institute of Cinematography, is a film historian recognised equally in the English and Russian-speaking worlds. He discussed the place of the studio in Russian film history, and the unique contribution of director Fridrikh Ermler, whose 1965 film, Before the Judgment of History (Pered sudom istorii) was screened at the Symposium.

6. Sergei Kapterev

Jeremy Hicks interviews Sergei Kapterev on Fridrikh Ermler and the Thaw.

Jeremy Hicks is a Senior Lecturer in Russian at Queen Mary University of London (UK). He is the author of Dziga Vertov: Defining Documentary Film (London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 2007) and First Films of the Holocaust: Soviet Cinema and the Genocide of the Jews, 1938-46 (University of Pittsburgh Press, forthcoming December 2012).

Jeremy Hicks is a Senior Lecturer in Russian at Queen Mary University of London (UK). He is the author of Dziga Vertov: Defining Documentary Film (London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 2007) and First Films of the Holocaust: Soviet Cinema and the Genocide of the Jews, 1938-46 (University of Pittsburgh Press, forthcoming December 2012). John Riley is a writer, lecturer, curator and broadcaster. His books include Dmitri Shostakovich: a Life in Film (I.B Tauris, 2005). He has contributed to books on film published by Cambridge and Oxford University presses, Routledge, Praeger, British Film Institute (BFI) Publishing and others. As a curator he has worked with the BFI, the BBC, the Barbican and others.

John Riley is a writer, lecturer, curator and broadcaster. His books include Dmitri Shostakovich: a Life in Film (I.B Tauris, 2005). He has contributed to books on film published by Cambridge and Oxford University presses, Routledge, Praeger, British Film Institute (BFI) Publishing and others. As a curator he has worked with the BFI, the BBC, the Barbican and others. Natascha Drubek is Heisenberg Fellow at the University of Regensburg, Germany. She co-edited Das Zeit-Bild im osteuropäischen Film nach 1945 (2010). Her book Russian Light. From the Icon to Early Soviet Cinema (Cologne, Böhlau Verlag) will be published in the end of 2012. She is film and screen media editor of artmargins.com.

Natascha Drubek is Heisenberg Fellow at the University of Regensburg, Germany. She co-edited Das Zeit-Bild im osteuropäischen Film nach 1945 (2010). Her book Russian Light. From the Icon to Early Soviet Cinema (Cologne, Böhlau Verlag) will be published in the end of 2012. She is film and screen media editor of artmargins.com.