Vision and Communism: The Films of Aleksandr Medvedkin and Chris Marker at “The Film Studies Center, Chicago” (Review Article)

The Films of Aleksandr Medvedkin and Chris Marker, The Film Studies Center, University of Chicago, October 12, October 19, November 2, 2011

In connection with the exhibition Vision and Communism at the Smart Museum of Art, Chicago, the films of Aleksandr Medvedkin and Chris Marker were shown at the Film Studies Center at the University of Chicago. Both the exhibition and the films are a part of the Soviet Arts Experience, an extensive series of 100 programs and events devoted to Soviet art and culture in twenty-six venues across Chicago. The massive nature of this experience demands attention to how Soviet art is perceived today. Although it is beyond the range of this discussion to offer a wholesale overview of Soviet or Communist art, this essay will focus on the relevance of Medvedkin and Marker as representatives of active, political filmmaking.

Presented thematically and over the course of three nights, this series spanned several decades of filmmaking and political developments, and included films ranging in time and place from the Soviet Union in the early 1930s to Washington, DC, in 1967 to Paris in 1968, and beyond. Thus, the spectator is required to make sense of these distinct historical moments and their representations. Since these films appeal for spectators to be critical viewers, one must consider the origin of these filmmakers’ concerns, for both Medvedkin, who is Russian, and Marker, a French Leftist director and filmmaker, share a mutual interest in audience reception.

Medvedkin and Marker met at the Leipzig Film Festival in 1967. Marker was drawn to the Russian director after he came across Medvedkin’s Happiness (Schast’e, 1934). Four years later, in 1971, Medvedkin came to Paris. He helped Marker and his collaborators organize a release of Happiness in France. Projections of the film were accompanied by Marker’s documentary The Train Rolls (Train en marche, 1971), which introduced Medvedkin’s Happiness, and also featured an interview with the Russian director. The Train Rolls begins with a montage sequence showing the impact of the Russian Revolution on film and other arts, after which Marker describes the organization of the film train and the crew’s activities in addressing social problems. The notion of film as fact, which is implicit in the notion that documentary filmmaking can provide proof of fact that will lead to social change, is emphasized by Marker’s direct, hand-held footage of Medvedkin (Catherine Lupton, Chris Marker: Memories of the Future (London: Reaktion Books Ltd, 2005), 128.). Marker’s film links the two men formally through choices that consciously acknowledge the filmmaking process and also intimately, on a personal and collaborative level. Unfortunately both The Train Rolls and The Last Bolshevik (Le Tombeau d’Alexandre, 1992), Marker’s ode to his departed friend, are noticeably absent from the Vision and Communism film series. While these films would have further informed viewers, their exclusion compels spectators to generate their own links between the films and filmmakers.

The thematic organization of the film series excludes biographic connections in favor of conceptual ones. The Film Train, the first installment of the series, included eight films that Medvedkin and a collective of other Russian filmmakers made aboard a specially equipped train in the 1930s, as well as one of Marker’s documentaries Class of Conflict (Classe de Lutte, 1968). Among other things, these films show involvement of the audience in the process of filmmaking. International, Intimate, the second set of films, including three films by Medvedkin and two by Marker, brought together varying approaches to political rhetoric and different appeals to the spectator. The film series concluded with Marker’s A Grin Without A Cat (Le Fond de l’air est rouge, 1977), which eulogized the Left that lay ruined in the wake of May 1968. The film incorporates a host of competing voices into a mosaic structure of images and narrative (Lupton, 143.). Reality is fragmented into different particles, moments, and images and the spectator is challenged to recognize some level of narrative substance.

The focus on audience reception on the part of Medvedkin belongs to a wider movement in Soviet Cinema of the 1920s that sought to “destroy” the passivity of spectators and to shape their perception. Early in his career, Medvedkin turned to what Nikolai Izvolov calls “man’s rough elegance,” a turn that produced a symbiosis between art and life. (Nikolai Izvolov, “Aleksandr Medvedkin i traditsii russkovo kino: Zametki o stanovlenii poetiki,” Kinovedcheskie zapiski, Number 49, Winter 2000, 25.) Medvedkin developed his approach to communicating with spectators during his time as a frontline cinematographer and theater worker during the Russian Civil War. His search for effective means of communicating with the ordinary citizens, workers and peasants who made up the Red Army led Medvedkin to combine various techniques and devices, including comedic turns and borrowings from folklore. The specially equipped “film train” actualized Medvedkin’s goal of direct engagement with the ordinary citizen. With the capability to process, edit, and screen films, the train brought cinema to the peasant masses and included the ordinary citizen in the filmmaking process. In these films, “every potential subject of the (camera’s) gaze could also be a potential viewer.” (Izvolov, 27.) For this reason, Izvolov defines Medvekin’s train films as belonging to a lived history, actively functioning in their viewing environment.

The short film pamphlets made aboard the film train addressed viewers directly and encouraged participation and self-awareness. These films were thought of as weapons, meant to give rise to debate. The crew organized small screenings in hostels, waiting rooms, and outdoor camps. Medvedkin’s ideal size for a screening was between seventy to 100 spectators (Emma Widdis, Alexander Medvedkin (London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 2005) p. 29.). According to Medvedkin, a group this size would allow spectators to undergo a shared experience while facilitating the organization of a targeted discussion. Medvekin’s film Mind Your Health (Beregi zdorov’e, 1929), for example, utilizes the combination of humor and medical facts to convey the necessity of personal hygiene on the part of the Red Army soldiers. The film is divided into mini-episodes that feature anecdotes related to health that rely on humor to communicate with the viewer. It features a bald private who grins and grimaces for the camera, usually framed in a close-up shot. In a more ominous scene, a squad of Red Army soldiers is cynically substituted for crosses, which represents the cost of bad hygiene.

Marker’s participation and organization of the work of the Société pour le Lancement des Oeuvres Nouvelles or SLON group also evinces attention to audience reception and collaborative filmmaking. The collective initially came together to make the omnibus film Far From Vietnam (Loin du Vietnam, 1967), which included segments from Jean-Luc Godard, Alain Resnais, Agnes Varda, Claude Leloch, William Klein, Michele Ray, and Joris Ivens. From this initial collection of filmmakers, Marker organized a collective of mainly technical workers along cooperative and nonhierarchical lines. The collective regarded itself as a tool “to help in the production of films made from a Left political perspective that would not otherwise exist.” (Lupton, 118.) In 1967, Marker was invited to the town of Besançon to observe the workers strike at the Rhodia textile factory. Marker recorded a three-hour interview with the striking workers and later, with members of SLON, made a film entitled Hope to See You Soon (A Bientôt, j’espère, 1968) about the strikers. (Lupton, 115.)

When the film was screened for the Rhodia workers some resented being represented as victims and thought that the film “gave a wholly pessimistic impression of their existence.” (Lupton, 117.) Others argued that the film depicted the workers as romantics by focusing on those seized by revolutionary fervor rather than depicting their daily struggle. Marker’s second film about striking workers, Class of Conflict, addresses the earlier criticisms of the Rhodia workers by focusing on a young union leader, Suzanne Zedet, who struggles for workers’ rights. The woman is first presented in 1967, isolated in her attempts to politically organize workers, and then again in 1968, as a more confident union leader ready to confront the management. Zedet’s transformation, represented through interviews and shots of her in action, suggests that Class of Conflict presents a particular focus on the intimate life of a political worker. The difference between the two factory films can be understood as a direct response to audience perception.

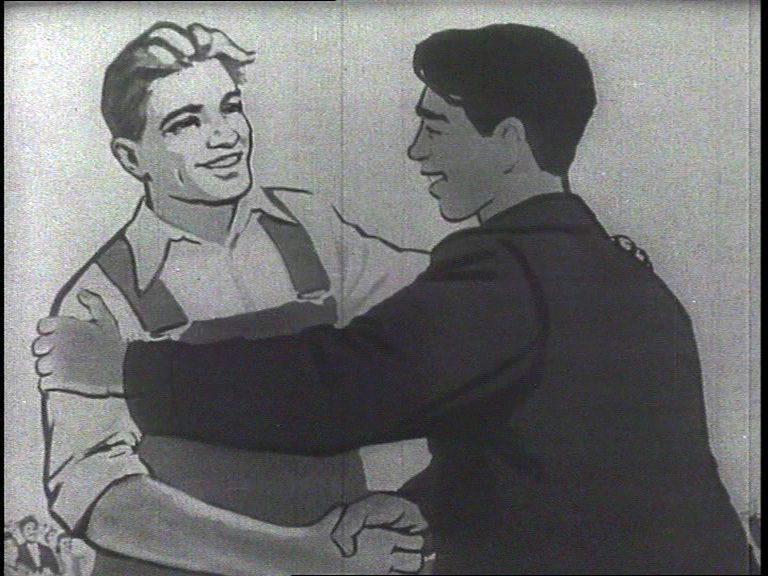

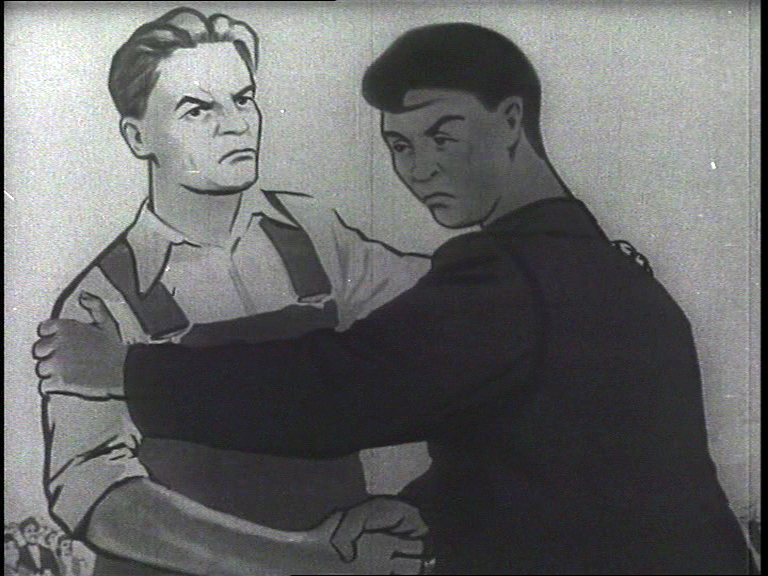

While Medvedkin’s train films and Marker’s films about the striking factory workers emphasize local and national concerns, the second series of films show their expanded interests in global issues. Medvedkin’s Law of Baseness (Zakon podlosti, 1962) positions the subjugated people of Congo in a history of capitalist exploitation. The film calls on theSoviet viewer to sympathize with the plight of the people of Congo. In this manner, Medvedkin’s documentary bears a resemblance to the posters of Viktor Koretsky on view at the Smart Museum of Art. Like Koretsky, Medvedkin also sought to construct an “Empathy Machine” that would pull viewers out of their daily existence as they identify with the pain and suffering of others. (Robert Bird, et al. Vision and Communism: Viktor Koretsky and dissident public visual culture, Exhibition Catalogue (Chicago: The New Press, 2011), 88.) Medvedkin’s documentary calls on the viewer to buy into the idea of shared sacrifice and humanist ambition, which is reliant upon the belief that this pursuit of world communism will ultimately be more invigorating, more life affirming, and more personally satisfying than a capitalist system of consumerism and desire for objects (Bird, 90.).

In The Sixth Side of the Pentagon (La Sixième face du Pentagone, 1967) and Embassy (L’Ambassade, 1971), Marker confronts the spectator with extensive handheld camerawork. The would-be occupation of the Pentagon by anti-war protestors in 1967 was filmed in the midst of the event and the handheld camerawork has a visceral and participatory effect. The spectator is pulled into these events by the camera’s proximity and intimacy. Marker further exploited this effect in Embassy, masking a fictional film as a documentary. The film mainly consists of cramped close-ups of a group of dissidents who seek refuge in an embassy after a coup d’état. It ends with an unmistakable shot of the Eiffel Tower, which alters the perception of the film but not the way spectators are asked to identify with the refugees in the embassy. Together these two Marker films remove the distance between the viewer and the object, utilizing the intimacy of the close handheld camerawork to involve the spectator in the event.

Looking back on the defeat of the Left in May 1968 on the streets of Paris and around the world, Marker’s A Grin Without A Cat also relies on his film’s ability to motivate the spectator to engage with the amalgam of voices and images his film represents. Marker claimed: “Each step of this imaginary dialogue aims to create a third voice out of the meeting of the first two, which is distinct from them.” (Quoted in Lupton, 143.) The film assembles a vast array of competing perspectives and events, which pushes the spectator to make sense of it all. But whereas Medvedkin takes up the position of earnest condemnation, Marker takes up “the very texture of received opinions.” (Lupton, 20.) Marker’s self-awareness is reflected in his sensitivity for the theater of political protest, which raises the dilemma of distinguishing between authentic revolutionary impulses and empty rhetoric. This sensitivity contributes to the effect of the film, which invites the spectator to recognize something sensible in the film’s assortment of narrative and visual segments, that is, to configure a historical plot line. In this manner, Marker leaves open the possibility of alternate endings and of history repeating itself.

Through Marker’s and Medvedkin’s varied approaches to the idea of Communism, their films raise questions regarding the relevancy of both the idea of Communism and Communist art today. In this regard, it is necessary to note that both the film series and the monumental Soviet Arts Experience coincide with a recent resurgence of the Communist idea, substantially represented by the volume of collected essays entitled The Idea of Communism, edited by Costas Douzinas and Slavoj Žižek. Alain Badiou’s contribution to this collection ends with a review of the current weak and dispersed state of political organization on the Left. In his introductory text, Badiou lays out the process by which an individual becomes incorporated in an ideological system. He emphasizes that a person first needs to be attracted to an idea before they make the decision to quit or commit, which is why reality must be exposed through fiction. ”Allegorical facts must ideologize and historicize the fragility of truth.” (Alain Badiou, “The Idea of Communism,” in The Idea of Communism, Costas Douzinas and Slavoj Žižek, eds. (London and New York: Verso, 2010), 12.) Thus for Badiou, works of art have the important function of circulating ideas. The Communism and Vision film series circulates the ideas of Marker’s and Medevdkin’s films and, following Badiou, they can be understood as attempts to deploy new possibilities. If their films are considered as presenting the still-active possibilities of failed ideas, then I argue one should view these films along the lines of what Žižek’s invites the Left to do in response to the 2008 financial meltdown and the massive bailout of banks, that is, ”to think – to think things through in a really radical way.” (Slavoj Žižek, First as Tragedy, Then As Farce (London and New York: Verso, 2009), 17.)

Žižek’s asserts that today’s Left needs a collective public hearing, where criticism can be voiced and faults admitted. Clearly the kind of event Žižek describes resembles the type of audience participation that Marker and Medvedkin sought to engender. In this regard, spectators should interrogate the feasibility of the kind of collective and active filmmaking represented in the early films of Medvedkin and Marker and the effectiveness of their later reliance on affect to motivate the spectator. The model of political action represented in these films, one of involvement, collaboration, and dialogue, and, most importantly, the communities they foster suggest an alternative to social relations mediated by images and dominated by commodities.

For a complete list of films and synopses, visit filmstudiescenter.uchicago.edu.

For more information on the Soviet Arts Experience see http://www.sovietartsexperience.org/.

Zdenko Manduši? is pursuing a joint Ph.D. in Slavic Languages and Literatures and Cinema and Media Studies at the University of Chicago. His areas of study are Russian/Soviet and Yugoslav cinema, film theory, and Russian and Southeast European Literature. He plans to write a dissertation based around the question of how the desire for innovation has inspired technological developments which has led to changes in film style and technique.

Zdenko Manduši? is pursuing a joint Ph.D. in Slavic Languages and Literatures and Cinema and Media Studies at the University of Chicago. His areas of study are Russian/Soviet and Yugoslav cinema, film theory, and Russian and Southeast European Literature. He plans to write a dissertation based around the question of how the desire for innovation has inspired technological developments which has led to changes in film style and technique.