The 46th International Film Festival in Karlovy Vary 2011 – An A-Festival with a Human Face (Film & Screen Media)

The Beginnings in 1946

Both have an art deco touch: the chunky gold-plated Oscar and the elegant brass statue of a female figure holding a glass globe. The Chrystal Globe, the Karlovy Vary Film Festival award, in its current shape was created only 11 years ago, but harks back to the decorative style of the first decades of the 20th century.(According to the festival dossier in the Czech monthly euro 27/6/2011, 77. The globe is produced by the traditional Moser glass factory (Karlovy Vary).) The festival is among the oldest in Europe.(It is the third oldest film festival after Venice (1932) and Moscow (first edition 1935, second in 1959).) It officially started out in the summer of 1946 in connection with the recent nationalization of the Czechoslovak film industry. Jindriška Bláhová, in her groundbreaking history of the festival, decribes its early “nationalistic” period dissolving into a “(pan)slavic” one in 1947.(J. Bláhová, “National, Transnational, Global: The Changing Roles of the Film Festival in Karlovy Vary, 1946–1956,” in: P. Skopal / K. Lars (eds), Film Industry and Cultural Policy in GDR and Czechoslovakia, 1945–1960, 2012 (in print).) After World War II, the Western Bohemian spa region which had a predominantly German-speaking population until 1945, needed an economical boost. A distinctly Czechoslovak event should claim back the area; no doubt, a film festival based on a nationalized cinematography was ideally suited for marking a “symbolically” new era with sympathy for socialist ideas and a strong orientation toward the USSR.

In the first years, the films were shown in two towns: Karlovy Vary (aka Karlsbad) and Mariánské lazn?, the former Marienbad(“In addition to the films presented by the nationalized film industry, films from countries with a strong movie making tradition like England, Sweden, the USA, and France were included. The number of films in the modest program (each day one film was screened three times at the Festival Theater in Mariánské Lázn? and was then shown the next day at the new Open Air Cinema in Karlovy Vary) was compensated for by the quality of the movies selected and by the accompanying program of social events.” (http://www.kviff.com/en/about-festival/festival-history/)) – a name which in 1961 would become well-known in cinephile circles through Resnais’ L’Année dernière à Marienbad / Last Year at Marienbad. From 1949 on, the festival only happened in Karlovy Vary. The first competition took place in 1948; this was also the year when the Grand Hotel Pupp (which was subsequently renamed “Moskva”) became the festival center. In 1978, the festival moved to the “Thermal” hotel.

1948: The “Alternative” Festival Becomes “International”

In 1948, the still rather local (that is: national respectively “Slavic”) festival metamorphosed into an arena of transnational political strategies. Bláhová shows how the Soviets’ lack of interest, still evident in 1947, (Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Alexandrov, Orlova, and film minister Bolšakov did not follow the Czechoslovak invitation and went to Venice instead (Bláhova 2012). In 1948 this situation turned around: in the wake of the Cold War the USSR started boycotting Venice and Cannes for allegedly “discriminating” against Soviet film production.) was transformed into a heightened interest in the Czechoslovak festival a year later. Suddenly the festival was called “international,” and in the following years, it was loaded with ideologemes like “peace” and “people” which went nicely with the pre-1948 stress on the aspect of “presentation of work” (“pracovní festival”). The Czechoslovak festival was now competing with Cannes and Venice on an ideologically level as well, showing the best film “work” made in the “peaceful” countries of the Socialist People’s Republics.

The “Brief Festival History” on the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival (KVIFF) website states that “the Communist takeover in February 1948 gave a new direction to the organization of the Karlovy Vary festival that lasted for several decades [.…] The program was put together with an awareness of the propagandistic strength of film and the importance of this medium as a tool in the ideological struggle against the West. Films included in the program had to reflect the new ‘film map of the world:’ space was given to film industries that were young and either just starting out or in revival.” http://www.kviff.com/en/about-festival/festival-history/

Interestingly, the festival tried from the very beginning to develop a profile that would set it apart from its Western peers. Bláhová describes how this “alternative model” increasingly became part of the Soviet strategy to contain American film business in Europe. From 1948 until the 1990’s the full-fledged Karlovy Vary Festival tried to find its identity somewhere between a niche in Soviet geo-political strategies and a “national” festival reaching out internationally.

Some of the “alternative” traits dating back to the early postwar period described by Bláhová still persist: a special attention to small film countries (mainly but not only in Eastern Europe); less “festival-like” (“festiválení”) (Bláhová quotes 1948 articles from the Czech press where parties and the presence of film stars and celebrities are considered a negative model which should be absent in this festival, which concentrates, in her words. on “work” and the social impact of film.) than other comparable festivals; and the lack of a film market. Compared to Berlin and Cannes, the festival today still does not see itself as a major player in international film business.

From Cinematic Staliniana to the First “Free” Festival in 1990

From 1959 to the early 1990’s, the Karlovy Vary Film Festival alternated with the then-revived Moscow International Film Festival.(The second edition of the Moscow festival was held after a long pause, in 1959. At that time the „International Federation of Film Producers’ Associations” granted only to Moscow. The Moscow Festival now precedes KVIFF by a couple of weeks.) To the great dismay of the Karlovy Vary Festival, the Kremlin in the late 1950s decided to have only one “A” festival for all the socialist countries. Effectively, this meant a downgrading of Karlovy Vary accompanied by a suspension of the coveted “A-Status”. Nevertheless Karlovy Vary, which was close to the West German border, remained an excellent venue for presenting film productions from Eastern Europe. The relatively large spa town not only could accomodate a high number of visitors, but the location also made it easier to attract guests from the West than was the case with the Moscow Festival.(Among the guests of the first five years were directors Abel Gance, Luis Bu?uel, Andrzej Munk, Giuseppe De Santis, Anthony Asquith, Sergei Gerasimov, Paul Strand, Joris Ivens, Mikhail Romm, Slatan Dudow, Jerzy Kawalerowicz or Alberto Cavalcanti. Film critics such as?Georges Sadoul and?Jerzy Toeplitz attended, and other guests included the actor Horst Buchholz and the poet Pablo Neruda. http://www.kviff.com/cz/o-festivalu/historie-rocniky/1948/hoste/#menu)

In its first decades, the Karlovy Vary festival had a clear geo-political task: it was a showroom mainly for ideologically sound filmsfrom the Eastern Bloc. After prizes for Wanda Jakubowska’s WW II drama Ostatni etap/The Last Stage (Poland) and Wiliam Wyler’s The Best Years of our Lives in 1948, the winners of the Crystal Globe in the subsequent years until 1956 were all from the USSR, starting in 1949 with V. Petrov’s Stalingradskaia bitva/The Stalingrad Battle. Mikhail Tchiaureli Was twice received a prize in Karlovy Vary. One prize, in 1950, went to his notorious docu-fiction epos Padenie Berlina/The Battle of Berlin 1&2 (this film, shot partly on trophy Agfacolor stock, was a present for Stalin’s 70th birthday).(http://www.kviff.com/cz/o-festivalu/historie-rocniky/1949/. In 1951 it was Yu. Raizman’s Kavaler zolotoi zvezdy/Knight of the Golden Star; in 1958 Tikhii Don by S. Gerasimov; in 1960 Seriozha/Splendid Days/A Summer to Remember by G. Daneliia and I. Talankin (for a clip from the ceremony, see http://www.youtube.com/user/HawkeyeMacLeod#p/search/18/UO7utc5_LXE)) The first prizes for domestic feature films came rather late. They were for Obžalovaný/The Accused (1964) by Ján Kádár, and Ji?í Menzel’s Rozmarné léto/Capricious Summer in 1968. Films like Pasolini´s Accattone and Tony Richardson´s A Taste of Honey were among the winners of 1962. In 1964, Elia Kazan came, and Karel Reisz was a member of the jury. In the second half of the 1960s, the festival started changing: “In a year of political regeneration peaking with the so-called Prague Spring, the organization of the festival fundamentally changed. Festival regulations were reworked: the traditional competition was not held and in place of the international jury three independent juries were set up (creative, acting, and technical).” (http://www.kviff.com/en/about-festival/festival-history/)

In the period of “normalization,” the festival suffered from the stifling atmosphere in a country where the experiment of “socialism with a human face” ended in August 1968 with a military intervention. “At the time, standards were only maintained in the informative section where viewers still had the opportunity to see key movies from world-renowned filmmakers, as well as films awarded at other festivals.” (http://www.kviff.com/en/about-festival/festival-history/).

After 1989, the audiences of the Karlovy Vary Festival were eager to see Czechoslovak films from the archives. In the 1990’s, the festival started shaping its future independently from outside influences; the first year when it stopped alternating with Moscow was 1995.

KVIFF and The Barrandov Studios

The ties between Soviet film production and post-war Czechoslovakia were not only political ones; a significant part of the prime production of the second half of the 1940’s was produced in the Barrandov studios in Prague. These are canonical examples of cult-of-personality films,(Oksana Bulgakova: Herr der Bilder – Stalin und der Film, Stalin im Film, in: Agitation zum Glück. Sowjetische Kunst der Stalinzeit. Bremen 1994, 65-69, N. Drubek-Meyer: Obszöne Rüschen russischer Giganten. Zum Kino des Spätstalinismus, n: P. Choroschilow, J. Harten, J. Sartorius, P.-K. Schuster (eds): Berlin – Moskau / Moskau – Berlin 1950-2000, Kunst aus fünf Jahrzehnten. Heidelberg 2003, 47-8.) like the mentioned The Fall of Berlin, the comedy Vesna/Spring with Soviet mega-stars Liubov Orlova and Nikolai Cherkasov, or Tchiaureli’s pseudo-religious Kliatva/The Vow (1946).

The Barrandov studio is a fascinating topic, although it is not very well researched in film studies. Thestudio south of Prague was created in the early 1930‘s by Miloš Havel, the uncle of ex-president Václav Havel. In its time, it was among the best European sound studios, and as such it became a coveted object. First, it was used after 1938 by the German UFA, with Havel struggling to keep up the number of Czech productions. Right after the war, it housed Soviet cinema productions.

Great expectations were created by the advertisements of the exhibition of 80 Years of the Barrandov Studios, which opened during the festival in the local art gallery (http://www.barrandov.cz/en/aktualita/barrandov-studios-80-years-exhibition). The show – displaying some of the pretty Cinderella costumes – was not only very small, but disappointing concerning the history of the studio. The curators of the exhibition obviously did not think it necessary to shed light either on the Nazi years or the Soviet use of the studio.

Serious Czech film historians, although they are generally enthralled by an empirical approach, to this day have hardly started to delve into the history of Czechoslovak film studios following the war. This history is yet to be written. It would also need to explore the connections between Soviet and Czechoslovak film production and exhibition, which appear still to be a taboo. The animosity towards the Soviet era has left this area under-researched.

The Festival in 2011

The main prize of the Karlovy Vary Festival is called the Grand-Prix Crystal Globe, and this year it went to an Israeli debut (Restoration, dir. by Joseph Madmony, 2010), based on a script which had won the Sundance Screenwriting Award 2011. More prizes in the main competition went to actor David Morse in another debut, Collaborator (Canada/USA 2010), by Canadian Martin Donovan, and to actress Stine Fischer Christensen in Die Unsichtbare / The Invisible (D 2011, dir. Christian Schwochow).

Although approximately 30 films are produced in the Czech Republic each year, no Czech film made it into the full-length feature film competition this time. Czech commentators saw in this outcome a weakness of Czech film producers to “profit from the glamour” of “Vary”(Marcela Alföldi Šperkerová and Adam Junek from the Czech journal euro were wondering why this is the case („Promarn?ný lesk,” in: euro 27/6/2011, 3).) (as Czechs call the town as well as the festival). Ji?í Bartoška, the Festival`s president, hints at another problem of this Western Bohemian spa town. Karlovy Vary finds it hard to attract other similarly high powered events during the rest of the year. Probably the low-key exploitation of the potential grandeur of the location is exactly one of Karlovy Vary’s, and also the festival’s, attractions. Although it is an excellently programmed and highly diversified festival and better organized than most other European counterparts, it still retains a comfortingly human face. By keeping the ticket prices low (the ratio to other festivals is between 1/5 – 1/3), KVIFF in even its 46th edition managed to be both a major international event and a festival accessible to regional audiences. “Region” here means cinephiles and young film fans from Central Europe who form a considerable part of the audience and who are able to share the spa water colonnades with John Turturro or chat with John Malkovich after his “Technobohemian” (http://www.technobohemian.it/) fashion show. Budgetwise, it is, of course, a small festival ($ 7,6 Mill.), which seems only logical as the Czech Republic is not a big country (it hasas many inhabitants as the urban area of Paris, that is 10.5 million).

Turning back to the “regional” films in the competition, a Slovak-Czech co-production about the Roma living in Slovakia (Cigán; directed by arthouse veteran Martin Šulík, this time choosing a no-frills style) was awarded the special jury prize, its young lead amateur actor, Ján Mižigár, receiving a special mention. One of the recently finished Czech films, which due to its national topic might have stood a chance,(Ibidem. Lidice is the name of the village which was totally destroyed by the Nazis as revenge for the Czech-British attack on leading SS man Heydrich. The burning of Lidice was carried on 10 June 1942.) Lidice (dir. by Petr Nikolaev), was released a month before the start of KVIFF, disqualifying it from participation. The pressing question is: why do some of the Czech films not have their premiere in Karlovy Vary? If one asks the programmers, there are two answers to be found. In an interview given to A. Junek and M. Alföldi Šperkerová, it seems that some film makers indeed „have a different festival in mind.”(Alföldi Šperkerová / Junek: “Hv?zdy si neplatíme,” in: euro 27/6/2011, p. 69.) Here, what does come into play is the fact that KVIFF does not have a regular film market, an important feature of its big regional competitor, Berlin’s Berlinale where a lot of Central and East European Films are screened.

Addressing this unpopular question, one could take into account the Czech mentality, which displays strong patriotism and self-deprecation at the same time. Some Czech filmmakers and their producers seem not to think very highly of their own local(Alföldi Šperkerová/Junek (“Promarn?ný lesk,” in: euro 27/6/2011, p. 3) use the word “provincial in the best sense of the word” by differentiating it from the “yearly merry-go-round of film business in Cannes or Berlin”.) festival, although their particular films might not succeed in any other cultural environment,(The reason for local (or: national) boundaries of many recent good films is often being explained with the most popular genre of Czech film, comedy. And comedies – especially if they are based on cultural specificity or puns untranslatable into other languages – allegedly do not travel very well. Especially if that culture does not belong to one of the English speaking ones…) and even though the KVIFF belongs to the so-called “A” festival category, making it part of the club of the big names like Cannes, Venice, or Berlin.

In 2011 this circumstance led to the fact that the audience was confronted with a surprisingly high number of very solid regional productions, such as Viditel’ný svet (The Visible World, 2011, dir. Peter Krištúfek) or Dom/The House by Zuzana Liovás (2011). However, both of these films are from Slovakia and both ironically feature first class Czech actors (Ivan Trojan and Miroslav Krobot). Whereas The Visible World had its world premiere in the Karlovy Vary City Theatre and competed in the highly observed section “East of the West,” The House had been shown already at the Berlinale in February. This film by a young Slovak director was chosen for “Variety’s Ten European Filmmakers to Watch.”

The competition “East of the West”has turned into a rather influential showcase of talent from Eastern and Central Europe,(This is why Eastern Europe delegates from other festivals (e.g. Nikolai Nikitin, the selector for Eastern Europe at the Berlinale), curators from the US and cinematheques prefer to come to Karlovy Vary to enjoy the preselection of films from the Eastern European, Post-Soviet (including the Baltic states and Central Asia) and Balkan areas.) which can be explained by its clear outline and branding, compared to popular, but „foggy” section titles like “Horizons” or “Forum.” Some of the “East of the West” films are cutting-edge and more deserving of attention than the films in the main competition. This was the case with last year’s „Special Mention” by the “East of the West” Jury, The Temptation of St. Tony (Püha Tõnu kiusamine, 2009) by Estonian director Veiko Õunpuu. This self-taught film-maker managed to add an Estonian flag to the European map of film countries. The dark Temptation of St. Tony seems to drive all Lynchean nightmares home in a (Post-)European country governed by rampant capitalism, incarnated in a severely hopeless black-and-white Estonia. The story of an odd couple (an Estonian business man and his randomly acquired Russian girlfriend) ends in a lethal club called Das Goldene Zeitalter (sic!). The film is an excellent example of a film with a truly global concern displaying a highly local feel. One could say the same about the two mentioned Slovak contributions in 2011 by Krištúfek and by Liová, only that they are less acutely interested in economical/national catastrophes but rather in the breakdown of Central Europe’s shrine of intimacy, the family.

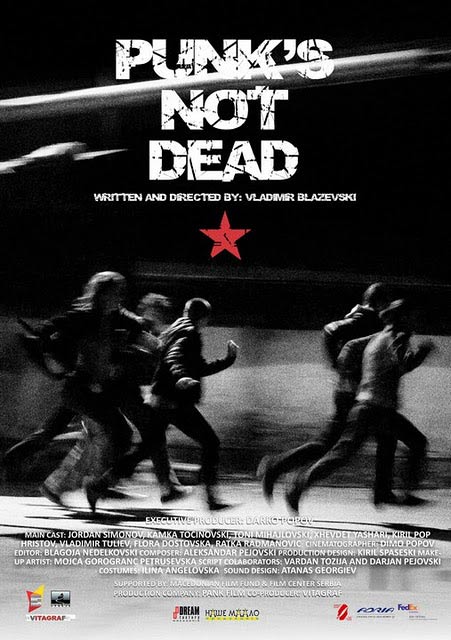

Many recent Czech films are set in the 1970’s: Ivan Trojan’s Identity Card and Pouta/Walking Too Fast by Radim Špa?ek. Osmdesát dopis? /Eighty Letters by Václav Kadrnka is set in 1987 (https://www.artmargins.com/index.php/podcast/119-interviews/647-vaclav-kadrnka-in-conversation-with-natascha-drubek). This year in “East of the West,” we find a Czech film that is not set in the past, Nic proti ni?emu/Nothing against Nothing (CZ, 2011). The debut of Petr Marek deals with the topic of adoption and NGOs. Here it should be mentioned that a third of all full-length features come from first directors, but in the section “East of the West” it rises to half. The prize in this section went to the road movie Pankot ne e mrtov (Punk´s Not Dead, Macedonia/ Serbia 2011, R: Vladimir Blaževski).

33 Women Directors and Judi Dench at the 46th Edition

Although venerated Eva Zaoralová stepped down from her post as artistic director, replaced by her colleague Karel Och, women directors stayed strong in KVIFF this year. Films by 33 women directors were shown (this makes 20%), among them Urszu?a Antoniak’s unsettling Code Blue (Netherlands/Denmark 2011, coproduced by Zentropa) which seems to be in dialogue with Temptation of St. Tony from last year. Antoniak’s figure is a fragile killer nurse; however, in the end, her lethal arts of intimacy have to succumb to the rather violent tastes of a man who shares her fondness of Doctor Zhivago. Both films chose scenes of sexual massacres as a representation of the state of the individual in (post-) European and Post-Soviet societies.

Most of these women directors are in their thirties and early forties, some even younger, including Ziska Riemann from Germany (her film Lollipop Monster, 2011, has been compared with the 1966 film Daisies by V?ra Chytilová, a female take on the Czech New Wave); Andrea Blaugrund Nevins with her documentary The Other F Word (USA 2010) about fathers in American underground music, which was a hit with the audience; young Lisa Aschan from Sweden with a film about malicious teenage girls Apflickorna/She Monkeys (Sweden 2011); Alex Stapleton with her enjoyable documentary on Roger Corman; Željka Suková with a semidocumentary hommage to her granny: Marijne/Marija’s Own)(This film was awarded the FEDEORA-Preis (Federation of Film Critics of Europe and the Mediterranean).), Alice Rohrwacher from Italy (Corpo celeste / Heavenly Body, 2011); Keti Machavariani from Georgia (Marilivit tetri / Salt White, 2011), and Zuzana Liová.

There are very few Czech women directors and they work mostly in the documentary genre, such as Erika Hníková who presented her film Nesvatbov / Matchmaking Mayor, CZ, SK 2010). The “matchmaking mayor” tries to improve the demographic situation in his village by cajoling its singles to choose a partner during Formanesque ballroom dances. A different type of matchmaker was film and theatre actress Judi Dench who said that now she found a “a wife” forher Oscar. She was talking about the female figure holding the Crystal Globe for Contribution to World Cinema, which was bestowed to her in Karlovy Vary in 2011.

The challenge for the festival is to keep the successful balance of local and international audiences, national and international cinema, and East and West. The 46th edition seemed to be fully aware of this role.