Ostalgia at the New Museum (Review Article)

Ostalgia, The New Museum, New York, July 14-October 2, 2011

Nostalgia has many guises – homesickness, yearning, desire, melancholia. Susan Stewart defines nostalgia as a “social disease,” a “sadness without an object,” a narrative that is fundamentally ideological. “Hostile to history and its invisible origins . . . ,” she argues, “nostalgia wears a distinctly utopian face, a face that turns toward a future-past, a past which has only ideological reality.”(Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (Baltimore and London: John Hopkins University Press, 1984), 23.) Walter Benjamin wrote about Leftist Melancholia as a kind of nostalgia that opposes true revolutionary thinking. But more recently, Viktor Misiano and others have proclaimed a progressive or radical nostalgia that sees the positive effects of memory in understanding the traumas of history.

The narrative of nostalgia defines the exhibition Ostalgia, an unconventional survey of more than 50 artists from various countries in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Republics, whose “main protagonist,” states curator Massmilano Gioni, is “the overarching ideology of Soviet Socialism.” The show’s title is taken from the German word Ostalgie or “nostalgia for the East” that emerged in the early 1990s to describe a longing for Germany pre-unification, and later elsewhere in Eastern and Western Europe as a collective mourning for the communist past. Shunning distinct geographical, temporal, even thematic delineations, Ostalgia presents viewers with an idiosyncratic and intentionally fragmentary portrait, or rather series of portraits, of life under socialist domination. At its heart is the role of the artist – and art –within and in response to this political condition, a position of both resistance and preservation.

Within the context of the New Museum, Ostalgia is very much intended for Western audiences, although artists such as Miroslaw Ba?ka, Anri Sala, and Roman Ondák are well known internationally, as are the handful of West European artists also included (Thomas Schutte, Simon Starling, Susan Philipsz, Phil Collins), whose individual works connect to the exhibition’s theme. Filling the entire fifth-floor gallery is a graphic timeline by the Petersburg-based collaborative Chto Delat? (What is to Be Done?), a kind of history lesson that marks the rise and fall of Cold War era socialism, beginning with the Yalta Conference in 1945 and ending with the dissolution of the Soviet Union on December 26, 1991. Placed within this timeline are three video projects: the Learning Film Group’s Vysocany Congress (2008), a re-enactment of the infamous congress that took place in 1968 in a factory in Prague two days after the Soviets invaded, and Dmitry Vilensky’s Perestroika Chronicles (2008), a montage of documentary films chronicling political reforms of the 1980s. Also included is Chto Delat?’s own Partisan Songspiel: A Belgrade Story (2009), a Greek tragedy of sorts that comments on the politics of present-day Serbia.

Within the context of the New Museum, Ostalgia is very much intended for Western audiences, although artists such as Miroslaw Ba?ka, Anri Sala, and Roman Ondák are well known internationally, as are the handful of West European artists also included (Thomas Schutte, Simon Starling, Susan Philipsz, Phil Collins), whose individual works connect to the exhibition’s theme. Filling the entire fifth-floor gallery is a graphic timeline by the Petersburg-based collaborative Chto Delat? (What is to Be Done?), a kind of history lesson that marks the rise and fall of Cold War era socialism, beginning with the Yalta Conference in 1945 and ending with the dissolution of the Soviet Union on December 26, 1991. Placed within this timeline are three video projects: the Learning Film Group’s Vysocany Congress (2008), a re-enactment of the infamous congress that took place in 1968 in a factory in Prague two days after the Soviets invaded, and Dmitry Vilensky’s Perestroika Chronicles (2008), a montage of documentary films chronicling political reforms of the 1980s. Also included is Chto Delat?’s own Partisan Songspiel: A Belgrade Story (2009), a Greek tragedy of sorts that comments on the politics of present-day Serbia.

Chto Delat?, which takes its name from Lenin’s famous quote, is known for its projects that combine art and activism with aspects of Soviet history under the guise of “art soviets.” Its declaration in the timeline’s introduction, “Our relation to history remains retrospective, but also anticipatory,” points to the use of nostalgia as a subversive tool, a theme that subtly reverberates throughout the exhibition but is explored more overtly in the show’s catalog. For instance, Misiano’s essay points, again, to a “progressive nostalgia” (also the title of an exhibition he organized in 2007), or the “return of memory” experienced in the 2000s after a period of “historical amnesia” that occurred in the wake of 1989. (Viktor Misiano, untitled essay in Ostalgia, catalog of the exhibition (New York: New Museum, 2011), 74.) Contributions by Joanna Mytkowska and Boris Groys look to the emancipatory possibilities of nostalgia. Rejecting today’s globalized art market and disillusioned with the cultural present, they argue for a return to the alternative models of the past as a means to art’s re-politicalization.

While the essays provide a lens through which to view the works in Ostalgia, the artworks themselves are representative of the historical moment in which they were created (both during and after the Soviet era) and the political conditions each moment dictated. Thus, the establishment of alternative models of art production was a strategy of survival. Some of the exhibition’s most interesting moments belong to those artists who worked outside of the Soviet system by staging subtle interventions in public spaces. Several text and photo-based works (dating 1976-79) document the performances of Czech-artist Ji?í Kovanda, whose actions on the streets of Prague would often solicit unsuspecting passersby, as in his Attempted Acquaintance. I invited some friends to watch me trying to make friends with a girl. . ., or XXX, On a escalator. . .turning around, I look into the eyes of the person standing behind me. . . (both 1977). For Self Fashion Show (1976), a black-and-white film transferred to video, the Hungarian performance and body artist Tibor Hajas stopped ordinary people on the streets of Budapest and asked them to model in front of the camera for one minute while the artist directed them on how to pose.

Slovakians Stanislav Filko and Julius Koller each invented their own brand of performance that often alluded to unearthly worlds. According to the show’s didactics, Filko created what he called “Happsoc” (the words happening and society combined), and “defined the reality of the city to be a kind of readymade.” On view were works from his Reality of Cosmos and Associations series (prints on cardboard, 1968-69) based on the Cold War space race. Koller, on the other hand, created “anti-happenings,” ongoing projects versus discrete actions, such as his U.F.O.-NAUT J.K. (U.F.O), (silver gelatin prints ranging from 1987 to 1997), in which he casts himself as an alien by obscuring his face with a plate, for example, and other ordinary objects.

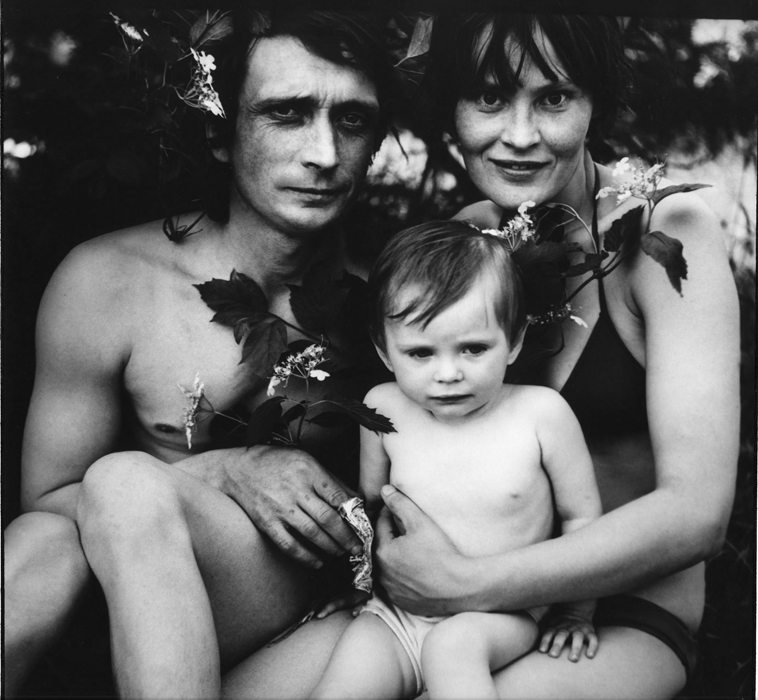

Other artists negotiated the realms of both the official and the unofficial. The Ukrainian Boris Mikhailov, for example, made films and photographs for the factory where he worked as an engineer. During the 1960s and ‘70s, he began taking nude photographs and was fired from his position when he used the factory’s darkroom to develop his images. On view were 84 chromogenic color prints from his Suzi Et Cetera series, comprised of erotica and other candid images of everyday life. Nikolay Bakharev similarly took photographs for an official arm of the factory where he worked in southern Russia. In order to earn some extra money and challenge himself artistically, he covertly solicited portraits on public beaches, one of the few places where one could expose one’s body openly. Bakharev began his project in the 1970s and continued over the course of several decades, eventually creating nude portraits as well. Fifteen gelatin silver prints from his Relationship and Type series were included here, and reveal an honesty and eros seldom witnessed.

The body as a subjective rather than an objective entity, free from political control, is unveiled in Evgenij Kozlov (E-E)’s The Leningrad Album (1967-73), 150 erotic drawings of male adolescent fantasy created when the artist was a teenager living within the close confines of a St. Petersburg communal housing complex. Feminist counterparts (and perspectives in general) are few in this exhibition, although Aneta Grzeszykowska offers a photo album of some 200 photographs taken while growing up in Warsaw during the 1970s and ‘80s. At first, images of childhood milestones and holiday celebrations appear indistinguishable from those found elsewhere, but when one discovers that the artist has digitally erased her image from each picture, a more complex narrative about the role of memory (and nostalgia) materializes.

The body as a subjective rather than an objective entity, free from political control, is unveiled in Evgenij Kozlov (E-E)’s The Leningrad Album (1967-73), 150 erotic drawings of male adolescent fantasy created when the artist was a teenager living within the close confines of a St. Petersburg communal housing complex. Feminist counterparts (and perspectives in general) are few in this exhibition, although Aneta Grzeszykowska offers a photo album of some 200 photographs taken while growing up in Warsaw during the 1970s and ‘80s. At first, images of childhood milestones and holiday celebrations appear indistinguishable from those found elsewhere, but when one discovers that the artist has digitally erased her image from each picture, a more complex narrative about the role of memory (and nostalgia) materializes.

More evocative are those works that look to the quotidian aspects of everyday existence, in which the rituals of private life reveal either psychological states of duress or subtle acts of resistance. In Armenian Hamlet Hovsepian’s silent, black-and-white video works from the 1970s, one witnesses anonymous figures engaged in the most mundane activities – a man scratching his back, another man yawning, a woman biting her nails –each performed within an empty, private world of tedium and entrapment rather than freedom from the politics of public life.

Vladimir Arkhipov’s Contemporary Russian Folk Artifacts (1960s/2011) is a photographic archive of tools and domestic items handmade by ordinary people that the artist collected while traveling throughout Russia. A radio receiver is reconstructed from scraps of metal, for example, and a TV antenna from bent forks; a shovel handle is cobbled from a wooden crutch. While the work speaks to the scarcity of basic household and consumer objects under socialist rule, it also pays homage to the utility and ingenuity employed for human survival, a handicraft of necessity Arkhipov likens to folk art. Conversely, Slovakian Roman Ondák’s ironical performance Good Feelings in Good Times (2003) underlines the hardship and, often, futility of waiting in line for food and other goods. Re-enacted for Ostalgia, various “actors” posing as common citizens would cue throughout the spaces of the New Museum, although what they were waiting for remained unknown.

Vladimir Arkhipov’s Contemporary Russian Folk Artifacts (1960s/2011) is a photographic archive of tools and domestic items handmade by ordinary people that the artist collected while traveling throughout Russia. A radio receiver is reconstructed from scraps of metal, for example, and a TV antenna from bent forks; a shovel handle is cobbled from a wooden crutch. While the work speaks to the scarcity of basic household and consumer objects under socialist rule, it also pays homage to the utility and ingenuity employed for human survival, a handicraft of necessity Arkhipov likens to folk art. Conversely, Slovakian Roman Ondák’s ironical performance Good Feelings in Good Times (2003) underlines the hardship and, often, futility of waiting in line for food and other goods. Re-enacted for Ostalgia, various “actors” posing as common citizens would cue throughout the spaces of the New Museum, although what they were waiting for remained unknown.

These existential meditations contrast with the many works that directly appropriate the icons of Soviet ideology, including several compelling collages by artists working in the late 1960s and ‘70s who manipulated the words and symbols of official propaganda as a form of political opposition. However, the inclusion of contemporary artists whose practice similarly uses the images and monuments of the Soviet past suggests something less oppositional, but rather a “nostalgia for the belief [once held] that change is possible and necessary.” (Joanna Mytkowska, untitled essay in Ostalgia, 76.) For example, Scottish-artist Susan Philipsz performs a haunting eulogy for the utopia socialism promised in her sound piece The Internationale (1999), a lilting rendition of this well-known anthem of international socialism.

In Lithuanian Deimantas Narkevicius’s video Once in the XXth Century (2004), a toppled sculpture of Lenin appears to be re-installed in a public square in present-day Vilnius. In actuality, the artist reversed footage of independence protests from Lithuanian national television. Both works intimate the loss of purpose and unity that defined different revolutionary movements, or, as Charity Scribner suggests in her Requiem for Communism, the “lost object mourned by many Europeans is the collective itself – collective labor, collective memory.” (Charity Scribner, Requiem for Communism (Cambridge and London: MIT Press, 2003), 98.)

In Lithuanian Deimantas Narkevicius’s video Once in the XXth Century (2004), a toppled sculpture of Lenin appears to be re-installed in a public square in present-day Vilnius. In actuality, the artist reversed footage of independence protests from Lithuanian national television. Both works intimate the loss of purpose and unity that defined different revolutionary movements, or, as Charity Scribner suggests in her Requiem for Communism, the “lost object mourned by many Europeans is the collective itself – collective labor, collective memory.” (Charity Scribner, Requiem for Communism (Cambridge and London: MIT Press, 2003), 98.)

The role of the media in documenting the political changes of 1989 and in shaping the collective imagination is explored in other works, including a video installation by Jonas Mekas, a pioneering figure of American avant-garde cinema. An émigré from Lithuania, Mekas culled over four hours of American news coverage of Lithuania’s declaration of independence from the USSR in 1990, which is streamed across four large monitors. One witnesses this historic event from both the perspectives of the drones of the nightly news and through the distant eye of an artist in exile. Auditions for a Revolution (2006), a film by the Romanian-born, Chicago-based Irina Botea, is a re-enactment of the 1989 revolution in Romania based on televisioncoverage, as well as video projects by Harun Farocki and Andrei Ujica. Botea enlisted students from the University of Chicago to impersonate various players involved in the events (members of the media, protesters, government officials). None of the actors knew Romanian, thus they read their lines phonetically, underscoring the disconnect between what is presented as reality by the media and what is actually remembered or understood.

This tension between reality and memory, between regressive and recuperative forms of nostalgia echoes throughout the exhibition, but one wonders if Ostalgia isn’t sometimes guilty of trafficking in the mental state it seeks to uncover. Missing is any critique of nostalgia and the dangers it portends, as evidenced by the return of conservative politics in many countries of the region. That said, there are a few works that address the rise of ethnic nationalism, such as Jasmila Zbanic’s video After, After (1997) that documents the effects of the Bosnian war on school children. The unresolved conflicts of the Chechen Wars are addressed by Romanian Andra Ursuta in her ink drawings of dead Chechen rebel soldiers based on images taken from the Internet. Russian David Ter-Oganyan’s makeshift bombs sited throughout the New Museum comment on continued acts of violence and terrorism.

One wonders why contemporary artists such as Israeli Yael Bartana and German Neo Rauch, whose videos and paintings, respectively, appropriate the aesthetic but not the politics of socialist realism as a new form of social critique, were not included in the exhibition. Especially given Bojana Pejic’s brief but poignant contribution to the catalog that seems to reject the idea of nostalgia altogether in favor of these kinds of critical practices. “I have focused my professional interests primarily on artistic positions that are critical of society, particularly the post-1989 democracies that embraced neoliberal concepts,” she states. “I strongly believe that political art, and feminist art in particular, offers the best possible social critique.”(Bojana Pejic, untitled essay in Ostalgia, 87.)

To that end, Anri Sala’s Dammi I Colori (2003) is well rooted in the social landscape of the present, and, thus, a bit at odds with the show’s overall premise. Mixing the best of political commentary and artistic intervention, the video profiles positive urban redevelopment in his native Tirana implemented under then mayor Edi Rama, a friend of Sala’s and an artist himself. The work tours Tirana’s transformation through the repainting of the facades of its worn buildings in a palette of vibrant colors. The entire city becomes a Mondrian-like painting, a monumental modernist grid, and an emblem of progressive artistic ideals. Click the photos to watch live sex on cam, or broadcast your own adult webcam by signing up for a FREE Watch hot Girl Alone shows on live sex cams Amateur Cams and Pornstars. Live Girls Languages English French Spanish Italian German Swedish Portuguese Dutch. We are pleased to welcome you on the best live sex cams site where you will find webcam girls from every corner of the world.

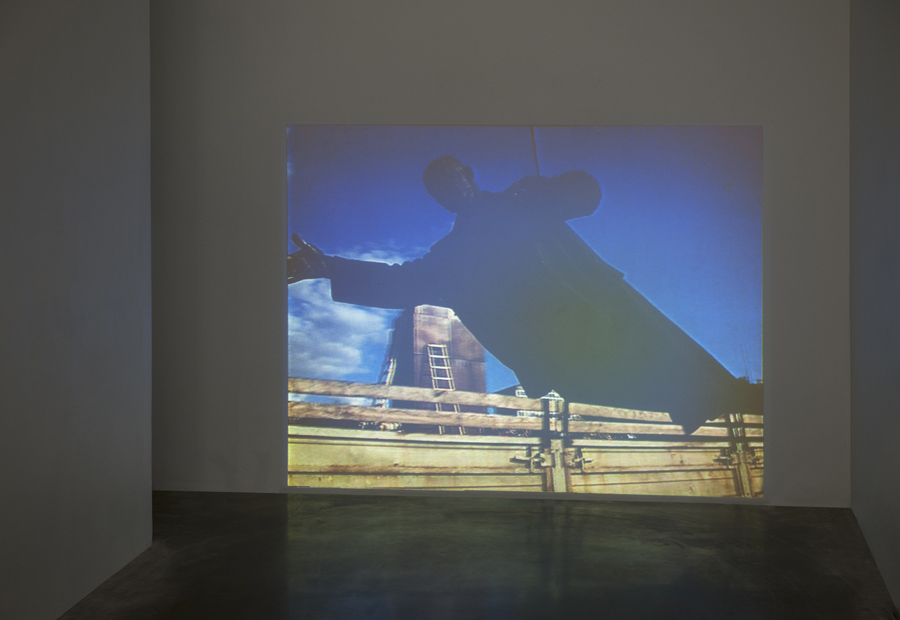

Ostalgia’s defining moment belongs to Phil Collins’s video projection marxism today (prologue) (2010), a series of interviews with women who taught Marxist-Leninist economics at universities and vocational schools throughout the former GDR. Each woman offers a candid account of her professional and personal life before and after socialism, sharing what was gained and what was lost. Interspersed throughout are archival segments centered mainly on pedagogy, as well as images from a contemporary university economics class. And while the challenges of the present seem to outweigh those of the past, the subjects’ reflections seem less nostalgic than simply honest. A similar dissatisfaction with the present post-communist condition is felt on both sides of the former Wall; Ostalgia offers a fascinating look back, whether or not one wears rose-colored glasses.

For another review of this show, see:

“Ostalgia At The New Museum (Review Article)” by Alise Tifentale