Shifting Perspectives on Curatorship (Article)

Introduction

A filmmaker, visual media artist, writer, teacher, curator and co-editor of ARTMargins, Allan Siegel has been involved in the experimental film movement and is one of the founding members of the documentary film collective Newsreel. He has taught at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, has exhibited work in New York, Chicago, London, Montreal, Pécs and Budapest, and is currently a lecturer in the Intermedia Department at the Hungarian University of Fine Arts.

In Hungary, prior to the political changes of 1989 (and then still for a good number of years afterwards) the practical opportunities for curating exhibitions independent of state policy or institutional prerogatives (linked often to the personal friendships and the personal outlook of an institution’s director) were severely limited. In this sense, and in parallel to the country’s other samizdat cultural movements, the beginnings of an independent curatorial practice could only gestate with partial visibility, waiting for openings that would only begin to appear in the 1990s. In a sense what happened after 1989 was the beginning of a mostly constructive interdependence of artists, on the one hand, and curatorial practice, on the other, that manifested itself much more confidently in the last years of the twentieth century. It would be a mistake to view this mature interdependence as simply a by-product of increased access to and mobility within the Western art world (although these are certainly factors); rather, it represents a series of reformulations, discoveries, and new critical perspectives on Hungary’s own cultural index.

Consequently, while it may be convenient to simply view the curatorial voices presented here within a context familiar to Western art institutions and curators, there are some significant distinctions. The “westernernized” framework, as a result of complex and developed relationships between museums, galleries, and collectors, reflects the realities of an art environment in which distinctions between the market place and museum-propelled curatorship are often blurred. In pre-1989 Hungary and similarly, by degree, in other former Eastern bloc countries, the art market was a marginal part of the cultural environment; it only began to emerge fully after the political changes of 1989. Therefore, market-driven curatorial devices appear later and even then they carry a distinct historical legacy.

What comes to the surface after 1989 are curatorial initiatives both outside and within institutional structures, which are themselves in transition. Within this messy conundrum of priorities and commodifications it is not surprising that it is frequently the more alternative exhibition sites and curatorial projects that represent new voices and critical frameworks within which an evolving praxis can be brought into the foreground and given the substance of a visible discourse. Along this trajectory, the unconventional as well as the established institution provides a laboratory within which these new voices can find an audience.

The young curatorial voices represented in this section of the ARTMargins Hungary Focus clarify processes of sifting through the past for linkages and continuities as well as forms of introspection and critical examination that flesh out a curatorial language that is often distinctly reflective of both Hungarian regional and global cultural realities.

Allan Siegel (Budapest)

Lívia Páldi

Lívia Páldi is currently a PhD candidate at the Institute for Art Theory and Media Studies, ELTE in Budapest. Since 2007, she has worked as chief curator of the M?csarnok / Kunsthalle Budapest. She was the curator of Other Voices, Others Rooms – Attempt(s) at Reconstruction. 50 Years of the Balázs Béla Studio, M?csarnok / Kunsthalle, Budapest (2009).

Lívia Páldi is currently a PhD candidate at the Institute for Art Theory and Media Studies, ELTE in Budapest. Since 2007, she has worked as chief curator of the M?csarnok / Kunsthalle Budapest. She was the curator of Other Voices, Others Rooms – Attempt(s) at Reconstruction. 50 Years of the Balázs Béla Studio, M?csarnok / Kunsthalle, Budapest (2009).

The last thirteen years that mark the period of my involvement in contemporary art have gone hand in hand with the recognition, interpretation, and reflection on what institutional work and a curatorial career might mean, and how they are responsible for initiatives and their enactment in different artistic/cultural environments in Hungary.

Starting in the second half of the 1990s, I spent a year at the SCCA-Budapest as assistant curator, which resulted in a partnership with my collegue János Szoboszlai. I became a co-founder and co-director of the Institute of Contemporary Art in Dunaújváros, a town founded by political motivations and called Stalin City between 1950 and 1960. Curatorial work there not only meant discussions about constructing a new type of institution, but the development of a program that engages in local issues (architecture, memory politics, etc.) and is able to connect with similar regional and international initiatives. Experimentation with an exhibition’s potential as a medium and a site of artistic production and presentation was given a special focus, and this enhanced the then-evolving debates around curatorial practice.

In Hungary, towards the second half of the 1990s, there was a strong commitment to map out the possible ways of overcoming the deficiencies in the mainstream art system and of taking stock of the types of missing or underrated agendas, practices, and functions that a contemporary art institution should and could have in a given environment.

At the time, mainly small or midsize institutions (mostly supported by international funds) practiced criticism through activity.(The League of Non-Profit Art Spaces (LIGA) was launched as a three-year long project in the form of a foundation with the substantial support of the Pro Helvetia Swiss Cultural Foundation. It incorporated six institutions, four of which were Budapest-based: Bartók 32 Gallery, Liget Gallery, Studio Gallery, Óbudai Társaskör and Cellar Gallery; and two operated outside of Budapest: Institute of Contemporary Art, Dunaújváros and First Hungarian Art and Artifact Repository Foundation, Diszel. It encouraged international and local collaborations, organisation of exhibitions, and publishing.) They not only proposed new strategies, questioning the effectiveness of those employed by central institutions (M?csarnok / Kunsthalle Budapest, the Ludwig Museum–Museum of Contemporary Art, etc.), but also implemented new approaches via international exchanges and long-term collaborations, and by creating channels to introduce issues like the notion of public art, gender issues, or activist practices, all with the aim of enhancing a wider discussion.(Among the many examples of this second wave, the activities of the tranzit network, the founding of the Erste Bank Collection, or the project Subversive Practices: Art under Conditions of Political Repression 60s–80s / South America / Europe in the Württembergischer Kunstverein Stuttgart could be mentioned. Apart from that what comes to mind is the ongoing research, exhibition and publication project The Former West, a contemporary art research, education, publishing, and exhibition project (2008-2013).)

At the time, mainly small or midsize institutions (mostly supported by international funds) practiced criticism through activity.(The League of Non-Profit Art Spaces (LIGA) was launched as a three-year long project in the form of a foundation with the substantial support of the Pro Helvetia Swiss Cultural Foundation. It incorporated six institutions, four of which were Budapest-based: Bartók 32 Gallery, Liget Gallery, Studio Gallery, Óbudai Társaskör and Cellar Gallery; and two operated outside of Budapest: Institute of Contemporary Art, Dunaújváros and First Hungarian Art and Artifact Repository Foundation, Diszel. It encouraged international and local collaborations, organisation of exhibitions, and publishing.) They not only proposed new strategies, questioning the effectiveness of those employed by central institutions (M?csarnok / Kunsthalle Budapest, the Ludwig Museum–Museum of Contemporary Art, etc.), but also implemented new approaches via international exchanges and long-term collaborations, and by creating channels to introduce issues like the notion of public art, gender issues, or activist practices, all with the aim of enhancing a wider discussion.(Among the many examples of this second wave, the activities of the tranzit network, the founding of the Erste Bank Collection, or the project Subversive Practices: Art under Conditions of Political Repression 60s–80s / South America / Europe in the Württembergischer Kunstverein Stuttgart could be mentioned. Apart from that what comes to mind is the ongoing research, exhibition and publication project The Former West, a contemporary art research, education, publishing, and exhibition project (2008-2013).)

Now, a decade later when the protagonists of this transformation hold leading positions in official, central institutions and should be able to implement the strategies developed during the preceding debates ona higher institutional and policy-making level, they have instead met with the recurring problem (a phenomenon partly inherited from Socialist times) that institutions are increasingly subject to (or victims of) new commercially infused political/ideological expectations.

The balancing of the different positions over the last two decades is far from satisfactory. Some of the main issues remain: the remote-controlling presence of the cultural administration; the lack of international experts; few long-term international cooperations and, last not least, the lack of a workable cultural policy (including the revision of support for the arts and its distribution; institutional reforms; cultural engagement of private parties, etc.). All these issues have resulted in an uneven, partially stagnating institutional/museum structure that supports isolated and in many cases provincial thinking, and which promotes a sporadic and fragile international presence and exchange without effective communication. All this nurtures and promotes a remote, isolated type of cultural existence in Hungary.

The strategies of examining social/human and power dynamics or of interrogating the past within a context of contemporary art differ quite significantly in the post-Socialist countries. In Hungary, apart from a few artistic and curatorial projects, artists focus more on formal issues and on the recycling of the neo-avant-garde tradition, and thus deal with the new social reality from an aesthetic point of view. A readiness to revisit and discuss the problematics of understanding personal and cultural remembrances, the politics of memory, the legacies of the two World Wars, the Holocaust, the (cultural) political and intellectual environment of the Socialist times and the transition period following 1989, appears explicitly only in isolated examples. The artistic discussions about history, identity, the body, and the construction of gender difference have been touched upon but have not become topics of major importance. Only a few artists have been willing to consider the complexities and politics of such engagement or to undertake projects based on in-depth research.(A few recent examples: Arthur Zmijewski, Radical Solidarity: http://www.trafo.hu/programs/1281 or Joanna Rajkowska, http://www.trafo.hu/programs/1489 or the group shows: Revolution I Love You http://www.trafo.hu/programs/1456 and Revolution is Not a Garden Party http://www.trafo.hu/programs/758 all produced/curated by Trafó Gallery.)

My curatorial interest and practice have largely been defined by issues of memory politics and the linking of the processes of memory and narration. For me, the interrogation of history via artistic projects has become a decisive line to follow in the last six years while I worked both as a freelancer and as a curator at M?csarnok. My show Second Present (2005) at Trafó Gallery combined different approaches that examine the official versus individual and subjective strategies of commemoration. Dealing with notions like authenticity, truth, objectivity, manipulation, and responsibility, the selected works drew attention to segments rarely discussed in historical representation. Almost all the participating artists worked with archival or appropriated archival materials. They showed the conflicts born out of different technical/theoretical and ideological approaches and the differences between the research and presentation strategies allowed and applied in science and the arts.

Shows like History Continued-Deimantas Narkevicius (2007) or !REVOLUTION? (2007/2008 together with Ulrike Kremeier) pointed to the need to reinvestigate norms and forms of preservation, cultural restructuring, cultural memory and identity, but within the changing parameters and demands of artistic and curatorial practices. These projects also strengthened my interest in the archive as a space/site where self-reflexiveness, responsible selection, mediation, and the experimentation with different methodologies and rules are all of crucial importance.

Prior to the recurring interest in the context and cultural-political strategies of the Cold War and their impact on the ”After-the-Wall” condition, the last decade gave impetus to the inventory and re-contextualization (and post-canonization) of less well-known Eastern European neo-avant-garde practices of the 1960s and ‘70s, which also helped open up the local cultural-social history of Eastern Europe to a wider discussion.

This is the context where one of my latest projects, Other Voices, Other Rooms–Attempt(s) at Reconstruction: 50 Years of the Balázs Béla Studio (BBS)(Other Voices, Other Rooms—Attempt(s) at Reconstruction. 50 Years of the Balázs Béla Studio, M?csarnok/Kunsthalle Budapest, December 16, 2009–February 21, 2010. Coorganizers: Hungarian National Film Archive, Béla Balázs Studio Foundation. Curated by Lívia Páldi with screenings and collateral events organized by Sebestyén Kodolányi.) explicitly defined itself as a cultural memory montage. It presented micro (hi)stories of the studio, highlighted by carefully selected pieces of documentation. These were taken primarily from the sub-cultural Hungarian neo-avant-garde and counterbalanced by excerpts from the history of the main official exhibition venue of the Kádár era, M?csarnok/Kunsthalle Budapest.

Positioned both inside and outside of the official sphere, BBS was a unique phenomenon. Its members kept pushing and circumventing the boundaries defined by the cultural apparatus while promoting reforms in both experimental and documentary filmmaking. The BBS films also provide insight into and offer a critique of Socialist ideology and its various manifestations. With its selection of over forty films, the show was pre-occupied with drawing a map (though only partial) of the networks and communities that existed within or in close proximity to the Studio. We used (documentary) photography, facsimiled documentation, and special groupings of artworks in order to (re)connect the forgotten or vanished spaces of sub-cultural life and production.

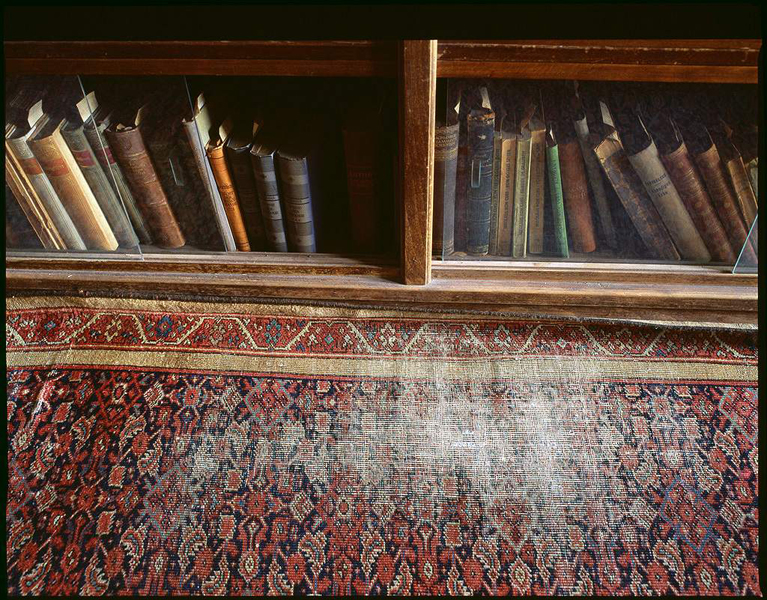

The key word was (re)construction, and the BBS show started as an inventory that presented fragments from different archives. It revisited some issues I have been involved with from the beginning of my practice: the imaginative potential of the exhibition as a tool and environment for the re-interpretation of cultural and political legacies. The show also presented photographs from an ongoing documentation of the Georg Lukács Archive–in collaboration with the artist and photographer Gabriella Csoszó–that forms the basis of the international exhibition and publication project Agitators, which will be presented in installments in 2011/2012.

Eszter Lázár (Translated by Zsófia Rudnay)

Eszter Lázár is a student in the Cultural Studies PhD Program at the University of Pécs. She has worked as a curator at the Hungarian University of Fine Arts and as an assistant lecturer in the Theory of Fine Arts Department at the same university. Lázár was the co-curator of the Over the Counter and The Phenomena of Post-socialist Economy in Contemporary Art exhibition at M?csarnok in Budapest (2010).

Eszter Lázár is a student in the Cultural Studies PhD Program at the University of Pécs. She has worked as a curator at the Hungarian University of Fine Arts and as an assistant lecturer in the Theory of Fine Arts Department at the same university. Lázár was the co-curator of the Over the Counter and The Phenomena of Post-socialist Economy in Contemporary Art exhibition at M?csarnok in Budapest (2010).

A few years back, at the invitation of the online journal Exindex, I wrote a short introduction to Jan Verwoert’s essay “Lessons in Modesty – The Open Academy as a Model.”(Jan Verwoert, “Lessons in Modesty–The Open Academy as a Model” Metropolis M (No. 5, 2006). http://www.metropolism.com/magazine/2006-no4/lessen-in-bescheidenheid/english (accessed 26 July 2010).) In his essay, Verwoert discussed the constraints imposed by the academic tradition of art education; the untapped opportunities–and the problems surrounding–the teaching of contemporary art, and the dark side of the institutionalization of “ideal models.”

It was no accident that I chose Verwoert’s text; I am interested in the often ambivalent relationship between contemporary art and education, not only with regard to my work at the Hungarian University of Fine Arts, but also as a curator. Back then, as an outsider lacking experience in teaching, I reflected on the points raised by Verwoert. After some years, with my experience in teaching, his ideas and the problems of education have taken on a new and more personal meaning for me.

In the Fall of 2009 the long anticipated Art Theory Program was launched at the Hungarian University of Fine Arts with fourteen students. The opening filled a gap that had affected the Hungarian art scene for decades. The course introduction on the university’s website states that “the program offers students basic and comprehensive training in art theory and curatorial practice… Since organizers of the contemporary art scene can only acquire the practical skills and knowledge necessary for exhibiting, archiving and documenting contemporary artworks from solely through their work experience, the B.A. scheme offers a program of study that offers comprehensive training in both the practical and theoretical aspects of this work.” Although it has been popularly referred to as a “curatorial studies program,” from its inception this three-year B.A. course is meant to lay the foundations for a soon-to-be-launched M.A. program in Curatorial Studies and Contemporary Art Theory. The Hungarian University of Fine Arts is one of the key educational institutes of contemporary art in Hungary. In international practice, the combination of art education and art expertise training is no new development (for example, the Royal College of Art and Goldsmiths College in London and the Hochschule für Gestaltung und Kunst in Zürich have already established precedents). Apart from a shared site of education, common curricular components, and the tangible results of “learning from each other,” this fusion provides a diverse and challenging testing ground for both sides. The scheme is expected to transform the basic, somewhat rusty, structure of Hungarian institutional systems and impact the mechanisms of Hungarian contemporary art, which are ripe for change. The common learning experience of art students and curatorial students and their jointly realized projects can also produce discourse-grounded collaborative projects.

In addition to my curatorial projects and my research with its aim to analyze critical approaches to art education (Models for a Fictional Academy, 2007; Visibility Works, 2008), as a member of a small but enthusiastic faculty I must also come to terms with the responsibilities and problems of teaching, as well as the challenges inherent in the complexity of the new task.

Verwoert, in his aforementioned text, takes the complicated and fundamentally non-consensual methodology of contemporary art education as the starting point of his discussion. His observations may prove useful in training future curators as well; as he writes: “one of the biggest dilemmas of teaching at an art school remains whether the right thing to do in order to support students is to help them to, figuratively speaking, clear their work up or to encourage them to embrace the unresolved conflicts of their work as a key to a more messy critical practice.”(Ibid.) This attitude not only requires more energy and a more highly focused self-reflexivity on the part of the students, it also demands continuous and sustained alertness in the teacher.

When establishing the basic principles for the Art Theory Program-together with János Szoboszlai (an art historian and chief curator at the Institute of Contemporary Art–Dunaújváros) and other experienced members of the faculty, it was our intention from the beginning to place a strong emphasis on a critical approach to practical training. This was designed to complement the specialized theoretical instruction with particular attention towards exploring the problems of visual art education, which comprises an important part of contemporary art. During the course of the first semester seminar, we worked on a subjective chronology of the history of the Hungarian University of Fine Arts, encompassing the period from its foundation in 1871 to an anticipated future date (2020). Instead of the “official” story of the institution, the students were asked to envision a special exhibition on the “rewritten” history of the University, based on freely chosen criteria and with the use of relevant dates, figures, and works.

During their first year, students became familiar with important sites of the Hungarian contemporary art scene. Leaders of museums and galleries introduced the mechanisms (mission statements, economic factors, collection concepts, temporary exhibitions, etc.) for the complex operations of these institutions. The lecturers invited for the Curatorial Studies course (József Mélyi, Nikolett Er?ss, Zsolt Petrányi, Edit Molnár, Hajnalka Somogyi, Barnabás Bencsik, Lívia Páldi, Gábor Ébli) spoke about their activities both in terms of their institutional background and within an international and historical curatorial context.

It is not only the students who are continuously learning: their questions and comments often raise points that were previously marginalized. Furthermore, in addition to contributing new approaches, “institutionalized” curatorial methods also became subject to reconsideration.

The practical part of the program is enriched by another special component: workshops that give students the opportunity to attend classes offered by the art programs (painting, sculpture, graphics, multi-media). Apart from giving students insight into the creative processes of visual art, a basic familiarity with the technical uses of fine arts media and graphic methods also gives future curators useful practical preparation.

In view of the experience gained in this first year I keep returning to a question that is also a fundamental component of Verwoert’s writing: what can be made of the position of authority we assume as soon as we begin to speak to others? Neither curatorial practice nor art practice has a comprehensive answer to this problem. Curating is a creative practice that requires theoretical grounding. While its guiding principles, methodology, and modes of realization might be givens, its points of departure, individual components, and contexts can produce varied solutions depending on the problems at hand.

One of the most crucial governing principles of curatorial practice also applies to teaching: instead of authority, which assumes a hierarchical type of relationship, curating presupposes mutuality and an equal partnership. There are no teachers who correct the students’ works; instead there are moderators who, after posing questions, allow space and time for potential answers, while also ensuring that the conversation can follow its course.

Discourse, like all projects, needs someone to speak up first, to seize the authority for questioning, to point to a problem and create the tension necessary for understanding what is at stake in the issue that is being discussed.(Irit Rogoff: ”Looking Away” in After Criticism, edited by Gavin Butt (Malden, U.S.A.; Oxford, U.K.; Victoria, Australia: Blackwell Publishing, 2005), 117-134.)

“How can you, as an artist, teacher, writer or curator, instigate and conduct a ceremony in which shared concerns are articulated through the joint effort of all present without tacitly assuming the role of the autocratic master of ceremonies?”(Verwoert.) Such authority should be limited to initiating the process, which is then carried on by the others.

The miracle of authority vanishes as soon as the teacher, the committed artist, or the curator recognizes that when faced with a problem his/her knowledge is just as insufficient as anyone else’s. This is the first step towards understanding that all participants have a role in finding a solution. In place of a hierarchical setup, this kind of situation creates a “momentary mutuality” that can only come into being when we tackle a problem or a conceptual/cultural challenge together.

The role of the teacher as a moderator and the discourse-based mutuality envisioned by Verwoert serve as the basis for the open-academy model. The institutional nature of universities, however, can often mean failure for even the most idealistic model as we face expectations and requirements such as a fixed curriculum, regulated quality requirements, and mandatory credit points. In spite of all this, inspiring conditions can be created even within an established framework. This cannot, however, be done without the support, participation, and activity of the students. It is in this way that view-altering perspectives can come into being, despite mandatory study times and exams; we become part of a learning process that cannot be measured in credit points.

The local and international community and network-building academic project I have outlined here may lay the foundations for the active membership of HUFA’s curatorial program and its students in the ever-changing international art community. It will also enable them to participate in the discussion of the issues with which the program is now confronted.

Beata Hock

Beata Hock is an independent researcher and curator based in Budapest. She holds a PhD in Comparative Gender Studies. In 2005 Hock published a book entitled Women’s Art and Public Art: Possible Interpretive Aspects for Two Kinds of Art Practice Emerging in the Past 15 Years.

Although I have had a few curatorial projects in the last five years or so, I cannot possibly call myself a curator, certainly not a full-time one. I also write, research, and teach. Furthermore, as the range of my current activities shows, my disciplinary background is fairly mixed, a fact that has important consequences for my curatorial and critical practice.

After earning my first degree in literature and aesthetics I began PhD studies at Budapest’s ELTEUniversity, exploring the historical “underground” sources of what later developed into experimental theater, performances, happenings, and related genres. Without being fully aware of it at the time, I embarked on what was actually a kind of counter-historicist research, trying to link these later forms of artistic expression to various cultural practices that largely remained unassimilated into larger narratives of canonical art history.

I later abandoned these studies for largely personal reasons, but the interest remained. As a holder of the national Ern? Kállai Grant for Young Art Critics and Historians, I spent three years researching, unearthing documents and building a digital database of Hungarian happenings, performance and action art of the 1970s and ‘80s at Artpool Art Research Center in Budapest. This period also brought with it inroads into the sphere of visual arts in general, but always with a focus on various kinds of “counter” practices of the 20th century.

A second MA (and later PhD) degree in Comparative Gender Studies consolidated another angle of inquiry for me: an interest in women’s creative activity and, more broadly, a gendered and explicitly feminist perspective on the sites, social conditions, and reception of cultural production. One would think that this approach fits a critical mind as this is where the contextual nature of both artistic and knowledge production comes into play.

Although feminist cultural critics consider their enterprise to be a political approach to reality-“a practice of constant theoretical provocation” (Griselda Pollock)-in the Hungarian context, women’s art is often viewed as just one of many fleeting artworld trends. Most of its practitioners and commentators actually avoid an uncompromisingly political and critical understanding of feminist practice. Some art historians do adopt the newly defined perspective, use its interpretive tools, and willingly prioritize gender in their aesthetic analyses. Meanwhile, artists explore gender codes and female identity in the de-politicized realm of the “personal.” For example, inquiring into links between feminism and the visual art scenes in non-Western European locations, Angela Dimitrakaki also noted an inability and unwillingness to articulate a radical consciousness in art and beyond.

I do not think, however, that the terms, thematic occupations and forms of feminist artistic practices in Central Europe have to be identical with the movement-like Western art practice of the 1970s and ‘80s, or with the “post-feminism” of later decades. In the “Second World,” the situation, discontents and demands-as well as the identity constructions-of women arguably were, and continue to be, different from those in Western capitalist democracies. This is where the recent show Gender Check painfully missed the mark inasmuch as it presupposed the identity of East-West political and gender identities, as well as unidirectional social-cultural processes.(Gender Check: Femininity and Masculinity in Eastern European Art; curated by Bojana Peji?. MUMOK, Vienna, November 13, 2009—February 14, 2010.) My impression was that the curator was looking for the emergence of readily recognizable “feminist” artistic rhetoric and subject-matter rather than leaving a more open space for the kind of gender-related critical interrogations that may emerge from within a different social and cultural context. Taking heed of Catherine Portuges’s warning of the risk of appropriating Second World realities by First World formulations, I am more interested in exploring the spaces (actual and virtual), the social voices, and the potentially different creative options available for feminist art production in our societies.

It partly follows from this that, unlike in my writing, women artists’ creative output does not usually occupy a central place in my curatorial practice, at least not in the form of women-only or women-focused single-issue shows. However, in my most recent project, Agents & Provocateurs (co-curated with Franciska Zólyom), individual and expressly gendered life strategies were posited as forms of opposition, redefining the private sphere as the terrain of resistance against social order.(Agents and Provocateurs featured over 30 international artists and was on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art—Dunaujvaros, Hungary (October–November 2009) and in Hartware MedienKunstVerein—Dortmund (May–July 2010); www.agentsandprovocateurs.net.) Thinking about women’s and men’s lives in this way, we did not isolate and elevate questions of gender beyond particular historical moments and societies, but instead engaged this category as it related, for example, to the strongly male-dominated and heteronormative, counter-cultural scenes of state-socialist countries. Presented with ample opportunity for preparatory research, we were able to locate such lesser-known artists and works as the Latvian Andris Grinbergs or the Hungarian Judit Kele, whose series of performances, I Am a Work of Art, was re-constructed and displayed for the first time in this exhibition.

It was this ability to combine the genres of research and exhibition that made Agents & Provocateurs something like a dream project for me. On this occasion, research results were publicized in a dialogical way, offering theoretically grounded ideas in an empirically explorable format. This ambience of a “study exhibition”, in addition to our methodologies, lent the project its interdisciplinary character.

Both at the stage of conceptualization and later, when the exhibition was already underway, I was asked whether or not I felt uncomfortable as a curator about working with and proposing such clearly defined thoughts in an art exhibition. I have answers to this question—as a curator and as a critically minded individual. As a curator (and as a visitor of exhibitions, for that matter), I have never really understood this cautious avoidance of well-formulated concepts that seems to have become acceptable in the art context. No one can seriously believe that either a “good” artwork or the interpretive behavior of a “good” beholder can be fully exhausted or governed by highlighting some selected facets of a work. This sounds to me exactly wrong. Artworks have multiple layers and audiences approach them with interpretive horizons stretching beyond what any single person—The Curator—could possibly control. What this person can do, however, is offer a springboard or a path into her own take on a particular subject, whereby the beholder will then choose whether or not to accept and follow that path. (This argument relates primarily to thematic group exhibitions and might have lesser bearing on solo shows.)

As a critically minded individual, I do favor interdisciplinary inquiries that by definition preclude a purely aesthetic approach to works of art. Edward Said persuasively argues for interdisciplinarity as the ultimate key to criticality, whereas so many experts in the arts and the humanities tend to be content with delimiting their own fields of inquiry and action, steering clear of other walks of social life.(Said, in fact, (in 1982!) refers to policy making as one such other field.) If they do so, no matter how poignantly critical their thought projects might be, they will forever be merely serving the interests of the powers that be, as they voluntarily perpetuate an arbitrary fragmentation of knowledge, forsaking any ability to see and think beyond their immediate professional preoccupations.

Adèle Eisenstein

Adèle Eisenstein is a freelance curator based in Budapest. Since she relocated from New York to Budapest in 1990, she has worked with the Soros Center for Contemporary Art and the Balázs Béla Studio. Her most recent exhibition was Donumenta 2010–Ungarn (Regensburg, 2010).

When asked to contribute to the Hungarian issue of ARTMargins, I responded that I was in the midst of planning a large-scale survey of Hungarian contemporary art of the last several years, to be shown in Regensburg, Germany, this fall, and that my best response would be to have someone review the show for ARTMargins. But I didn’t get off the hook so easily. Co-editor Allan Siegel asked me to note my observations on planning the show, set within the context of what I have seen and experienced on the Hungarian art scene over the last two decades I have been living in Budapest.

The show that opened in Regensburg this past September is part of an on-going series, each year featuring the art and culture of another country along the Danube, including a large contemporary exhibition, as well as film, theater, dance, music, and literature. The subtitle of Donumenta 2010–Ungarn is “Liberation Formula,” and the title for the following series of observations takes its departure from my introductory text in the catalogue.(The artists shown in donumenta 2010–Ungarn: “Liberation Formula” are: Ádám Albert, Zsolt Asztalos, Erika Baglyas, Borsos-L?rinc, Mária Chilf, István Csákány, Attila Csörgi, Dániel Erdély, Róza El-Hassan & Salam Haddad, Dániel Horváth, Balázs Kicsiny, Szabolcs KissPál, Ádám Kokesch, János Korodi, Éva Köves & Andrea Sztojánovits, Gábor Arion Kudász, Adrián Kupcsik, Jen? Lévay, Little Warsaw, Ilona Lovas, Erik Mátrai, Csaba Nemes, Tamás Oszvald, Ákos Siegmund, Miklós Surányi, Ágnes Szabó, Dezs? Szabó, Eszter Ágnes Szabó, Péter Szabó, Kamilla Szíj, Beatrix Szörényi, Hajnalka Tarr, Zsolt Tibor, Gyula Várnai, Júlia Vécsei. The compilation of video works also includes those by: Sándor Bodó, János Borsos, László Csáki, Szacsva y Pál. Co-curator: Áron Fenyvesi.)

In an interesting twist of fortune, as I was considering what to write, I attended a discussion on Pál Gerber’s retrospective show (I’m Looking For a Choir that Still Sings and a Laundry that Still Washes) at the Ludwig Museum Budapest. On the one hand, the discussion refreshed my memories of the past; on the other, it made me realize that we may have finally come full circle, with some of Gerber’s works similar to a number of works by younger artists.

But to note where I began in putting together the list of artists and works to be shown in Donumenta, keeping in mind that most of the previous shows have also come from Central/Eastern Europe, I tried to focus on what was special about Hungary. I thought about what was interesting and surprising for me when I first arrived here from New York in 1990.

I quickly acquired a great vantage point, working at first informally with the Soros Center for Contemporary Art, and formally for the Balázs Béla Studio, which had been the only experimental film studio operating in Communist Hungary (as a workshop since 1959, and as an official production studio from 1961 onwards). I also soon began organizing shows and events in underground, “alternative” spaces. The first–“the smallest gallery in Hungary”–was what concretely connected me with the Danube in February 1991, the Folyamat Gallery, which operated together with experimental filmmaker Gábor Császári in the water-measuring house on the Danube next to the Chain Bridge (until 2000). My favorite project of all was the “Turkish Bath” space, which I ran together with artist Hilda Kozári in an abandoned copy of a Turkish Bath (built 1924, opposite the Lukács Baths), where we arranged mainly one-day events in the spring and summer of 1992-96.

Aside from the direct connection to the Danube which is present in the show (Ádrian Kupcsik’s The Ten Longest Rivers in Hungary, or Ilona Lovas’s S.O.S., not to mention Péter Forgács’s Danube Exodus, which was shown in the film program), I thought about the significant role of science, invention, and mathematics–as well as the high number of world-renowned Hungarian photographers and filmmakers (especially in Paris, New York and Hollywood). I realized just how much this knowledge permeates daily life, as well as art, in a way that seems to be quite unparalleled. This is especially tangible in the oeuvres of Attila Csörgi and Gyula Várnai, who both seem to work more as alchemists or engineers than purely as fine artists. Csörgi carries out serious and extensive research employing the theorems of geometry and the laws of physics, engineering devices (cameras, optical apparati) on his own in order to then use them in his experiments. He visualizes phenomena that usually are imperceptible to the naked eye, mixing science with an approach that is at once playful and philosophical.

One section of the Donumenta show was subtitled “Underdog Genius: Math and Science in Hungarian Art.” The section for the first time places Csörgi’s works in the same context as those of Dániel Erdély. Erdély is originally a graphic designer who worked with his father, Miklós Erdély, in the various art/creativity/visuality groups led by the artist, but his creation of the space-filling Spidron began in a class taught by Ern? Rubik. The Spidron is a planar figure consisting of two alternating sequences of isosceles triangles which, once folded along its edges, exhibits extraordinary spatial properties.

Continuing from that pairing, we enter a sort of “laboratory” space which contains the microscopes and circuit boards of Zsolt Asztalos, the “Hatchery” of Ádám Kokesch, as well as Dezs? Szabó’s scattering of “sensors,” “satellites”, and photographs which portray catastrophe and its aftermath but which also represent a kind of “laboratory” setting. Rooms adjoining the “laboratory” contain works by Little Warsaw (a succinct, direct re-contextualisation of history) and Szabolcs KissPál, another artist who is part engineer and part alchemist.

János Korodi’s massive paintings deconstruct the space in which the viewer stands. A good example of innovation in photo and film are the collaborative multi-media installations of Éva Köves and Andrea Sztojánovits. Köves’s paintings and painting installations draw deeply on the Constructivist and Bauhaus traditions, which emphasize the geometry of the architecture. The recent collaboration between Sztojánovits and Köves’s is a natural successor and 21st century version of the school of László Moholy-Nagy, Walter Ruttmann and Viking Eggeling.

The exhibition featured a large section on socio-political current events in Hungary, with a special focus on the Roma question, as well as a glimpse of the transition to “democracy.” This political emphasis is where I find some hope for the future, even if the present is not looking so bright. While it might seem as if the political atmosphere now is at 180 degrees from where it was when I arrived in Hungary, I feel we have come full circle, in a strange way. To be more precise, I am heartened to see an increasing number of artists respond to political questions, and this time, not in a subtle code or underground, but out in the open. Aside from the dramatic swing to the right, particularly after this spring’s elections, there is the especially tragic Roma question, and a large number of artworks respond directly to current events in the news. For instance, Csaba Nemes’ Remake animation series can be seen as a reaction to the anti-government protests of 2006, while his series of oil paintings addresses the recent spate of Roma tragedies.

Of course, socio-political and economic current events, crises and disasters do not end at the borders of Hungary, and an increasing number of artists directly address global issues affecting us all. These include a large group of works by the artist pair Borsos-L?rinc, with new additions to their Mask series and a new portrait of the pope.

There is also János Korodi’s work Heliocentric, which is the reproduction of a real carpet woven in Afghanistan; and a series from Zsolt Asztalos, War in Gaza, is even more topical now than when it was produced last year. Also in this group belongs Róza El-Hassan’s latest piece (in collaboration with Salam Haddad) which is part of her video series of performances, R. thinking/dreaming about overpopulation. The series began in the fall of 2001 with an action to commemorate Yasser Arafat’s gesture of donating blood for the victims of 9/11 as a positive and compassionate gesture to combat the wars of the world.

Has the “formula” changed over the past twenty years? I would say that it has, although there is continuity as well. The Soros Foundation still exists, but with a greatly reduced role in arts funding; the C3 Foundation has also been transformed and the Museum of Fine Arts hosts high-visibility shows that cater to the city’s increasing tourist population. As for my own formula or strategy, I continue to work as a freelance curator, writer, editor and translator, as well as spending a good deal of my “free” time on the board of Amnesty International Hungary.

János Szoboszlai (Translated by Adèle Eisenstein)

János Szoboszlai has worked as a visual arts program coordinator for the Soros Center for Contemporary Arts, as director of the Institute of Contemporary Art–Dunaújváros, and as a special visiting lecturer for the MA in Arts Administration program at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Most recently, he has co-owned and run the acb Contemporary Art Gallery in Budapest (2003-2009). Currently Szoboszlai works as a Senior Lecturer in the Art Theory Department at the Hungarian Academy of Fine Art and as the Chief Curator at the Institute of Contemporary Art–Dunaújváros.

As a curator who became anart dealer and then returned to the public sector I have gained experience from observing the needs and wants of the public as well as those of the private sector. On the one hand, I see serious problems in the field of cultural policy in Hungary; on the other hand, I still consider myself an enthusiastic cultural worker despite the friendly fire that occurs everyday.

The private sector purchases and collects contemporary art and trusts in the arrival of the secondary market because it invests and hopes for profit, and quite rightly so. A small number of private individuals also practice patronage, likewise quite correctly. They support artists in their own philanthropic and bourgeois way because they can do so, and in this way they ensure a lasting position in cultural history for themselves and for their families. At the same time the private sector criticizes the institutional system that makes use of public money because it squanders, without much efficiency, public funds that do not amount to very much to begin with. According to these criticisms, the state collects very little and without a real agenda, and it carries out its domestic and international promotion of contemporary art rather badly. The private sector is absolutely right about this. Yet at the same time the public sector does contribute something through its financing of scholarly research, art periodicals, scholarships, universities, exhibition spaces, and museums. However, it must do all of this within the obsolete financing and methodological framework inherited from the former regime.

The artist strives for success in intellectual and material terms, while the private sector would like to turn a profit–in the end these goals converge in that artist names that are well known on the international scene are also beneficial for business. In Hungary we still do not have such names, and investors rightly call the professional institutions to task regarding this absence. Since the political changes in Hungary, countless grievances as well as constructive proposals have been delivered to each successive minister of culture with the demand for institutional reform or, to use a more global terminology, a new and effective “cultural policy.” By now it is not only artists, curators and the leaders of exhibition spaces who make their voices heard. Business is also knocking at the door of state administration. In the best of cases, this is done to insist on collaboration but also, less elegantly, to ask directly for public money. Setting aside the concept of spending public funds, we must also take into consideration the fact that art lies within the sphere of interest of the private sector.

How should the relationship between contemporary art and business or more precisely a “public-private partnership” evolve in Hungary? Taking the above into account, I can only speak about the necessity of laying a foundation. While the state takes on the basic financing of contemporary art and its institutional framework, manages institutional functions (education, publication, collection, etc.) and promotes Hungarian art domestically and internationally, it does not wish to spend more on these activities than what it is currently spending. Therefore it is necessary to develop a concept for a coherent policy regarding contemporary art (read: financing). And in this, the ambitions of the private sector must be taken into account. An understanding of the big picture as well as expert knowledge in the field are necessary in order to realize a concept for practical cultural policy. A clear framework for financing must be a top priority. Here the interests of the business world must be allowed to assert themselves even though its activities should be suitably supervised. All decisions should be taken together with the institutions of the state sector on a professional basis.

In September 2009 I left the art market, where I had worked as a gallerist, to work as chief curatorat the Institute of Contemporary Art–Dunaújváros. Previously, I served as the institute’s first co-director (with Lívia Páldi), and later as its director between (1997-2001).

Dunaújváros was built for political and economical reasons in 1949, following a resolution passed by the Stalinist government of Hungary, the Central Directorate of the Hungarian Worker’s Party. In 1950 the Party decided to construct a massive new iron-smelting complex with a housing development next to it. The city–named Stalin City–with its 40,000 inhabitants and industrial complex was the product and incarnation of the industrialization of the 1950s, of its Socialist-Realist architecture and the utopian dreams of the totalitarian regime.

The Institute of Contemporary Art–Dunaújváros (www.ica-d.hu) has been organizing contemporary art projects since 1997, and its predecessor, Uitz Hall, did so since 1992. The municipal government ensures the Institute’s basic operational upkeep. Since its establishment in 1997 the ICA-D has always been a creative and innovative contemporary art center that acts as a multifunctional, non-profit institution which organizes and coordinates national and international art projects. The Center’s focus is on art production, exhibitions, residency programs, and its own collection. ICA-D has gained a good international reputation and a strong position in Hungary.

Since the beginning of 2010 we have been re-organizing and modernizing the ICA-D by launching new working structures andmethods, and by introducing a marketing and communication strategy. Instead of one person (the previous director, always an art historian) being responsible for practically everything (from curatorial work to fundraising, communication, organization, etc.), a curatorial team has been established consisting of two Hungarian curators, a non-Hungarian curator (with a term lasting for two years), and myself. Besides exhibiting and lecturing on aspects of the national and international scene, our goal is to build up and maintain a vigorous and productive cooperation with artists and theoreticians. We also aim to launch, coordinate and document analytical research on contemporary art as well as to exhibit and maintain the Institute’s collections and to initiate projects that might bring in new works of art.

Since 2009 the Institute’s new leadership has been preparing for a structural shift that would not only ensure more efficient project financing and communication, but also render possible more intensive local participation in the formation of the city’s cultural profile. Since the last general elections in 2010, the new national government enjoys the votes of more than two-thirds of Hungarian voters. The state administration responsible for culture is being re-organized, and a new director is being appointed to the National Cultural Fund. Thanks to news leaks, some troubling information has come to light regarding the reputation enjoyed by contemporary art-including theater, literature, film, music, and fine art–in official circles. Whatever the nature of the new government’s cultural policy, local policies will look precisely the same. This atmosphere naturally pushes us to intensify the push for an “educational turn.” The exhibition-making institutions are educational centers in themselves, but due to this new situation, the ICA-D must play a particularly active role in the city’s educational structure, providing art and art-related programs for students of the city. It must do so both in order to be more integrated into the organizations of Dunaújváros and to ensure the institution’s survival. In January 2010, the Municipal Government declared that this year the ICA-D has become unsupportable financially from the perspective of the municipal budget. The ICA-D then asked for solidarity from Hungarian and international professionals, as well as from the wider public and launched a website (www.help.ica-d.hu). By March 22nd 2010, more than 1500 signatures had been collected. It is still not clear why, but on May 25th the Dunaújváros City Council decided to continue the city’s support for ICA-D into the second half of 2010.

We can conclude from all this that any attempt to operate a cultural institution with public money makes that institution vulnerable since the reputation of contemporary artists, curators, and critics is highly negative among those who make the financial decisions. In short, it is high time that some light was shed on what “responsibility,” “expectation,” “priority” and “partnership” mean to our policy-makers. Since it seems that fulfilling the original mission of the ICA-D is not enough to ensure our political and financial stability, our center needs to launch new programs of public education, cultural tourism, and public relations.