Aesthetics and Politics: Critical Art in Hungary Today (Article)

Critical art practices (once also labeled avant-garde) have been playing out their death throes ever more dramatically in recent years.(For a historical and theoretical reconstruction of the death throes of avant-garde art in the 20th century, cf.: Paul Mann, Theory-Death of the Avant-Garde (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991).) On the one hand, this might be so precisely because more and more artists, curators, and collectors have taken an interest in them; but on the other hand, if they do die out definitively, then the real danger exists that there will be no alternative at all to global techno-capitalism in the art world and entertainment industry. As for Hungary, Miklós Erdély and Ákos Birkás already buried the avant-garde in the early eighties, its tombstones still lurking in the shadows of T?zoltó Street, its ideals hovering over the exhibitions of Liget Gallery, Trafó and M?csarnok/Kunsthalle. However, based on the inaugural AVIVA Prize nominations in 2009 and the AICA Prize a year before, one might presume that critical art once again (or rather, finally?) prevails.(The AVIVA Prize was founded by the AVIVA insurance company in cooperation with M?csarnok/Kunsthalle in 2009. It offers the largest monetary prize (five million forints, appr. 15.000 Euros) in the Hungarian art scene. All AVIVA Prize nominees must be under forty. The AICA Prize has been awarded by the Hungarian Association of Art Critics since 2008.) Moreover, owing to Tranzit (tranzit.blog.hu), “critical art” can now become a significant factor in the Hungarian critical scene, based on the theory of, for instance, Jacques Rancière and Irit Rogoff, as well as the activity of young Hungarian curators.(For instance, Hajnalka Somogyi’s 2008 exhibition Try Again. Fail Again. Fail Better at the M?csarnok/Kunsthalle, or Nikolett Er?ss’s 2009 Vacuum Noise at the Trafó Gallery.)

If we simplify things, critical art shows two different and almost completely contradictory trends that nevertheless blend into each other. One trend is associated with Clement Greenberg; the other with Guy Debord. In vulgar materialist terms, in Greenberg’s case, the means is the end, while in Debord’s the end justifies the means. For Greenberg, the zenith of art was the aesthetic purification of the medium based on its specific characteristics (e.g. the material of painting, or its two-dimensionality); for Debord, on the contrary, art was at best a device that could be appropriated in order to expose the author’s committed critique of ideology. Even though both thinkers at one time professed Marxism in some form, Greenberg believed in the artwork and its autonomy, while Debord rejected aesthetic autonomy and deeply despised the exploitative capitalist industry of the spectacle (that is, practically everyone other than him). Greenberg was fascinated by apolitical, aesthetic subversion defined in contrast to kitsch, while Debord was not even interested in such an aesthetic of subversion, as for him it was bad enough if something had any aesthetic features at all.

The death of the avant-garde smothered the Greenbergian tradition of medium-specific art in Budapest in the eighties, and “medium-specificity” still remains occluded by the locally applied labels of media art and conceptual art.(Neo-avant-garde art, with its focus on issues related to the media, has been equally criticized after its live burial by new sensibilities (the European version of the “populist” postmodern) and the neo-conceptual critical art of the 1990s. Thanks to the democratic transition in Hungary and Central and Eastern Europe, the problem of ideology came to the forefront in the ’90s, replacing other issues concerning the medium in post-socialist social critique and feminist critique alike.) All the more so since in Hungary excessive interest in the medium itself (its materiality) can provide grounds for charges of “commodity fetishism” by critically and politically engaged artists. And this accusation implies serious risks in an anti-capitalistic and post-Marxist international scene. Meanwhile Debord’s interpretation of critique has seen a global renaissance since 2011. With the September 11 attacks and the images from Abu Ghraib and the war on terror, Hardt and Negri’s Empire has manifested itself in a form that gives new and distressing meaning to late capitalism as well as to the pictorial turn. A generation away from the state-socialist anti-capitalism of the Kádár-era, the critique of the prevailing “imperialist” world order and of the “exploited” modern subject has, for now, become fashionable in Hungary as well. The 2009 nominations for the first “Hungarian Turner Prize” (the AVIVA Prize) showed the growing popularity of critical art on the younger scene (under forty).

I won’t hail Miklós Mécs as a local superstar since he doesn’t even have any “real” artworks to show for himself. Of course, if he did then he would be making a mistake since he is not a conceptual artist but a Situationist. For that reason — he should not make any kind of fetishized object. I would prefer if for his next prize, instead of drawing himself a Hitler-moustache that reads “BEUYS,”(The pronunciation of “Beuys” is very close to the Hungarian word of moustache (bajusz).) he would write a commentary on the famous parody of the SZ.A.F-manifesto,(SZ. A. F. (AMBPA) is an abbreviation for the Association of Mouth and Brain Painting Artists, established by Mécs shortly after he graduated in 2007, together with Judit Fisher. The practice of mouth and brain painting suggests conceptual thinking, on the one hand, and the critique of painting associated with popular image production, on the other.) which would mean to pay tribute to Guy Debord. Or, he could at least evoke the prominent Hungarian post-Situationist artist Miklós Erhardt instead of the ever-so-distant Joseph Beuys. Parenthetically, and for the sake of sobriety, I should note that one need not have read The Society of the Spectacle in order to have anti-capitalist ideas.(Guy Debord’s works (The Society of the Spectacle, 1967; and Commentaries on the Society of the Spectacle, 1988) were translated into Hungarian by Erhardt, who also embedded them in Hungarian artistic life through various exhibitions.)

I won’t hail Miklós Mécs as a local superstar since he doesn’t even have any “real” artworks to show for himself. Of course, if he did then he would be making a mistake since he is not a conceptual artist but a Situationist. For that reason — he should not make any kind of fetishized object. I would prefer if for his next prize, instead of drawing himself a Hitler-moustache that reads “BEUYS,”(The pronunciation of “Beuys” is very close to the Hungarian word of moustache (bajusz).) he would write a commentary on the famous parody of the SZ.A.F-manifesto,(SZ. A. F. (AMBPA) is an abbreviation for the Association of Mouth and Brain Painting Artists, established by Mécs shortly after he graduated in 2007, together with Judit Fisher. The practice of mouth and brain painting suggests conceptual thinking, on the one hand, and the critique of painting associated with popular image production, on the other.) which would mean to pay tribute to Guy Debord. Or, he could at least evoke the prominent Hungarian post-Situationist artist Miklós Erhardt instead of the ever-so-distant Joseph Beuys. Parenthetically, and for the sake of sobriety, I should note that one need not have read The Society of the Spectacle in order to have anti-capitalist ideas.(Guy Debord’s works (The Society of the Spectacle, 1967; and Commentaries on the Society of the Spectacle, 1988) were translated into Hungarian by Erhardt, who also embedded them in Hungarian artistic life through various exhibitions.)

Let me recap the story of Mécs’ success and let us see what a critical artist can do with the various state-funded and privately founded awards he/she receives, and which are a measure of his or her success. Mécs’ artwork, entitled Achilles and the Tortoise, was literally made out of the 2007 Prima Primissima Prize. This led to the nomination for the AICA Prize. In the meantime Mécs’s partner, SZ.A.F., pocketed the Herczeg Klára Prize.(Sándor Demján, one of the most influential businessmen in Hungary, funds the Prima Primissima Prize. The Studio of the Young Artists’ Association awards the Herczeg Klára Prize.) In 2009 came the AVIVA Prize nomination, which in itself was equivalent to an award, and the rejection of which brought the artist a Major János Prize. This was courtesy of Tamás St. Auby who presumably valued the critical gesture of his disciple highly and who perhaps also liked the fact that Mécs had presented him with his most famous work to date (or at least with the value-less part of it, the part that could not be converted to cash), a flipbook made from banknotes.(Szentjóby established the Major János Prize from his own Munkácsy Prize (a national award), naming it after a forgotten Hungarian avant-garde graphic artist, still alive at the time.) For that work Mécs drew different parts of the legendary race between Achilles and the Tortoise onto 100 each of 50-euro banknotes he received with the “bourgeois” Prima Primissima Prize. He then proceeded to cut them into half in such a way that the bigger halves (the ones showing Achilles) could still be exchanged at a bank, while the smaller halves (the ones with the tortoise) were made into a flipbook. This accomplished, Mécs and SZ.A.F. went on to celebrate with what they called an immediatist potlach at a non-profit gallery in Budapest, in the refreshing shadow of Hakim Bey’s nomad philosophy.(A selection of Hakim Bey’s writings (among them Immediatism, which has inspired SZ.A.F.) was published in 2008 in Budapest.) It would be an understatement to say that the exhibition turned out to be ephemeral. It did at least evoke the best-known theoretician of ontological anarchy (Bey) who, like Debord, saw media and mediatization as the worst curses of globalized capitalism.

Let me recap the story of Mécs’ success and let us see what a critical artist can do with the various state-funded and privately founded awards he/she receives, and which are a measure of his or her success. Mécs’ artwork, entitled Achilles and the Tortoise, was literally made out of the 2007 Prima Primissima Prize. This led to the nomination for the AICA Prize. In the meantime Mécs’s partner, SZ.A.F., pocketed the Herczeg Klára Prize.(Sándor Demján, one of the most influential businessmen in Hungary, funds the Prima Primissima Prize. The Studio of the Young Artists’ Association awards the Herczeg Klára Prize.) In 2009 came the AVIVA Prize nomination, which in itself was equivalent to an award, and the rejection of which brought the artist a Major János Prize. This was courtesy of Tamás St. Auby who presumably valued the critical gesture of his disciple highly and who perhaps also liked the fact that Mécs had presented him with his most famous work to date (or at least with the value-less part of it, the part that could not be converted to cash), a flipbook made from banknotes.(Szentjóby established the Major János Prize from his own Munkácsy Prize (a national award), naming it after a forgotten Hungarian avant-garde graphic artist, still alive at the time.) For that work Mécs drew different parts of the legendary race between Achilles and the Tortoise onto 100 each of 50-euro banknotes he received with the “bourgeois” Prima Primissima Prize. He then proceeded to cut them into half in such a way that the bigger halves (the ones showing Achilles) could still be exchanged at a bank, while the smaller halves (the ones with the tortoise) were made into a flipbook. This accomplished, Mécs and SZ.A.F. went on to celebrate with what they called an immediatist potlach at a non-profit gallery in Budapest, in the refreshing shadow of Hakim Bey’s nomad philosophy.(A selection of Hakim Bey’s writings (among them Immediatism, which has inspired SZ.A.F.) was published in 2008 in Budapest.) It would be an understatement to say that the exhibition turned out to be ephemeral. It did at least evoke the best-known theoretician of ontological anarchy (Bey) who, like Debord, saw media and mediatization as the worst curses of globalized capitalism.

But what should an artist who is critical of the emphasis on media and their materiality do in this impossible situation, a situation that proclaims intimacy and immediacy as the only acceptable human and artistic alternative? Well, they have two choices. They can either relax as SZ.A.F. admirer Tibor Horváth did at Budapest’s Liget Gallery with his show O2 (Outsiders Out, 2009). Or, they can eject any aesthetic element from art and turn it into something solely political. This is what Miklós Erhardt did with his heart wrenching and depressing Retrospective a few weeks later in the same venue. As a good Situationist, Erhardt took political commitment very seriously (for this is the only way it can and should be done) and he showed where the radical critique of a society of spectacle can lead, namely to the fetishization of both artworks and artists.(Erhardt’s and Dominic Hislop’s Big Hope projects (e.g. Re:route or Talking About Economy) have always been directed at socially relevant issues such as impoverishment, homelessness and immigration.)

But what should an artist who is critical of the emphasis on media and their materiality do in this impossible situation, a situation that proclaims intimacy and immediacy as the only acceptable human and artistic alternative? Well, they have two choices. They can either relax as SZ.A.F. admirer Tibor Horváth did at Budapest’s Liget Gallery with his show O2 (Outsiders Out, 2009). Or, they can eject any aesthetic element from art and turn it into something solely political. This is what Miklós Erhardt did with his heart wrenching and depressing Retrospective a few weeks later in the same venue. As a good Situationist, Erhardt took political commitment very seriously (for this is the only way it can and should be done) and he showed where the radical critique of a society of spectacle can lead, namely to the fetishization of both artworks and artists.(Erhardt’s and Dominic Hislop’s Big Hope projects (e.g. Re:route or Talking About Economy) have always been directed at socially relevant issues such as impoverishment, homelessness and immigration.)

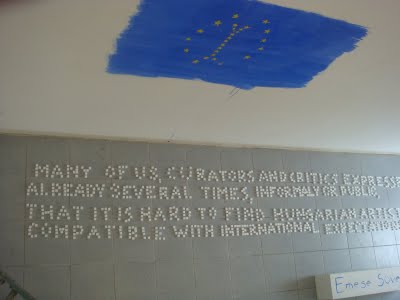

At his O2 show Horváth invited his artist companions-Sándor Bodó, Miklós Mécs, Csaba Uglár, Tamás St.Auby-to joke about the social and professional expectations we bring to art. In the same year, Emese Süvecz wrote a controversial blog in which she argued that Hungary lacked contemporary artists who conformed to international expectations. Reflecting on this, Horváth set the following citation from Süvecz in sugar cubes on the floor at his O2 exhibition: “Many of us, curators and critics expressed already several times, informally or public, that it is hard to find Hungarian Artist compatible with international expectations [sic].”(At a later exhibition the piece was given the somewhat vulgar title, EU-conform Butt.) The metaphor of the “centaur’s horse” describes well the artistic medium that was denounced by Mécs and Horváth, and that was sublimated by Erhardt into a political philosophy. Art historians in the meantime find it hard to abandon the presumption that something can be considered art only as long as it reflects social reality through its own particular medium. Therefore, the centaur is a centaur specifically by virtue of its (partial) nature as a horse. In other words, it is the “lower” part of his or her body that changes the human into a centaur. We can ground the age-old oppositions of subject vs. medium; spirit vs. matter; and philosophy vs. crafts in this composite being. The emphasis in the controversial phrase “critical art” should be on art and not on critical theory, however sublime it may be. If we subtracted all ideological content from the philosophical poetry of Szentjóby or from his film Centaur (1975), or if we took the cultural politics of the group Société Réaliste away from its work Cultural States, then what is left to see would be very close to the kind of culture of the spectacle from which these works were born.(Szentjóby’s emblematic film Centaur (1975) was finally screened at the 11th Istanbul Biennial, curated by WHW. Another Hungarian participant in this rather Brechtian biennial, Societé Réaliste (Ferenc Gróf and Jean-Baptiste Naudy), presented one of its most voluminous works, Cultural States (2008), which reflects on twentieth-century European political and social history via enormous and decorative illustrative maps.)

At his O2 show Horváth invited his artist companions-Sándor Bodó, Miklós Mécs, Csaba Uglár, Tamás St.Auby-to joke about the social and professional expectations we bring to art. In the same year, Emese Süvecz wrote a controversial blog in which she argued that Hungary lacked contemporary artists who conformed to international expectations. Reflecting on this, Horváth set the following citation from Süvecz in sugar cubes on the floor at his O2 exhibition: “Many of us, curators and critics expressed already several times, informally or public, that it is hard to find Hungarian Artist compatible with international expectations [sic].”(At a later exhibition the piece was given the somewhat vulgar title, EU-conform Butt.) The metaphor of the “centaur’s horse” describes well the artistic medium that was denounced by Mécs and Horváth, and that was sublimated by Erhardt into a political philosophy. Art historians in the meantime find it hard to abandon the presumption that something can be considered art only as long as it reflects social reality through its own particular medium. Therefore, the centaur is a centaur specifically by virtue of its (partial) nature as a horse. In other words, it is the “lower” part of his or her body that changes the human into a centaur. We can ground the age-old oppositions of subject vs. medium; spirit vs. matter; and philosophy vs. crafts in this composite being. The emphasis in the controversial phrase “critical art” should be on art and not on critical theory, however sublime it may be. If we subtracted all ideological content from the philosophical poetry of Szentjóby or from his film Centaur (1975), or if we took the cultural politics of the group Société Réaliste away from its work Cultural States, then what is left to see would be very close to the kind of culture of the spectacle from which these works were born.(Szentjóby’s emblematic film Centaur (1975) was finally screened at the 11th Istanbul Biennial, curated by WHW. Another Hungarian participant in this rather Brechtian biennial, Societé Réaliste (Ferenc Gróf and Jean-Baptiste Naudy), presented one of its most voluminous works, Cultural States (2008), which reflects on twentieth-century European political and social history via enormous and decorative illustrative maps.)

The creative distance between the signal and noise (as the technophile and anti-humanist Friedrich Kittler would say) that characterizes innovation and progress is much more marked in works by Tamás Kaszás and István Csákány. At the AVIVA Prize exhibition (at Budapest’s M?csarnok), Csákány exhibited the concrete statue The Worker of Tomorrow. The statue presents “empty” firefighting gear that has been prepared for deployment, while the title evokes the Pharisaic rhetoric of multinational firms (the “worker of the month”). Kaszás in his turn has researched socialist culture for a long time, and this is why it was refreshing to see him build, at the same exhibition, a utopian piece inspired by Russian constructivism (Yakov Chernikov). The piece – made from plants and exhibition waste found inside the M?csarnok building-is entitled Conference of the Plants, which refers to the spiritual ecological philosophy of the early twentieth century.

The creative distance between the signal and noise (as the technophile and anti-humanist Friedrich Kittler would say) that characterizes innovation and progress is much more marked in works by Tamás Kaszás and István Csákány. At the AVIVA Prize exhibition (at Budapest’s M?csarnok), Csákány exhibited the concrete statue The Worker of Tomorrow. The statue presents “empty” firefighting gear that has been prepared for deployment, while the title evokes the Pharisaic rhetoric of multinational firms (the “worker of the month”). Kaszás in his turn has researched socialist culture for a long time, and this is why it was refreshing to see him build, at the same exhibition, a utopian piece inspired by Russian constructivism (Yakov Chernikov). The piece – made from plants and exhibition waste found inside the M?csarnok building-is entitled Conference of the Plants, which refers to the spiritual ecological philosophy of the early twentieth century.

The greatest success among the medium-conscious artists at the AVIVA Prize exhibition was Emese Benczúr who showed a beautiful and well thought-out work. The medley of dots of which it was made-paper circles of approximately 5 cm in diameter hanging on strings-showed its random aesthetic when you looked at them from up close, while from an elevated vantage point at the other end of the hall they revealed a written message: “find your place.” Ádám Kokesch’s work, on the other hand, lacked any such vantage point. His glass paintings and photographs are intentionally enigmatic and medium-conscious. The devoted spectator might think initially that it is precisely the blind spot between theory and politics to which these objects point, as they positively dispel any meaning. Meanwhile, one might be aware that not only are they descendants of non-figurative painting and image architecture, they also expressly draw on the late modernist cult of high-tech and design. In other words, Kokesch’s objects are very much political, as they are both post-Marxist and anti-capitalist. Compared to this, Little Warsaw’s cultural politics is too direct, while their avant-garde aesthetics (for instance, the “reconstruction” of Szentjóby’s neo-avant-garde action) is perhaps not tangible enough. Play best gun games site. (Tamás St.Auby (aka Tamás Szentjóby) performed his action again in 2005 at Little Warsaw’s studio. The event was documented. The photograph is entitled Reconstruction and it was the first piece in Little Warsaw’s Tableux Vivant project.) I understand that they work with a subtle shuffling of meaning and context (overemphasized by the simplifying mass media and the uninformed large public), but the legendary Expulsion-Exercise–Punishment-Preventive Autotherapy (1972) will remain Szentjóby’s iconic work either way, while Qualities (2001) keeps losing more and more of its post-socialist charm.

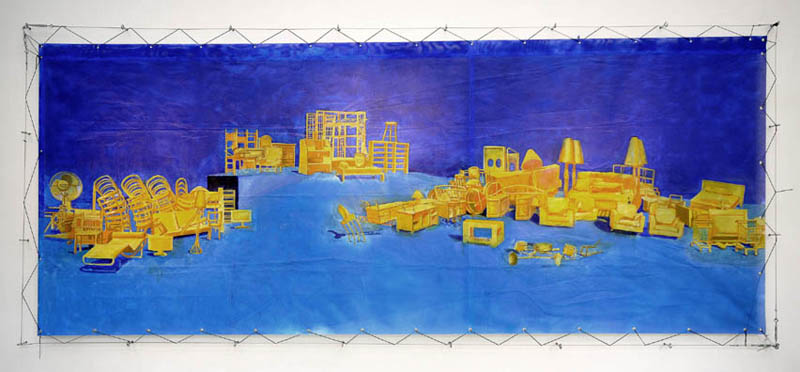

Let’s take a look behind the prize-giving machinery. Why was the winner of the AVIVA Prize so predictable? Tibor Horváth had opened a blog for betting on the winner of the AVIVA Prize, even assigning the odds. The prediction was that Little Warsaw was the most likely winner, offering the lowest multiplier. And they won. Perhaps today Little Warsaw are the most successful artists just under forty, they are the ones who represent “Hungarian contemporary art” most reassuringly.(By “reassuring” I mean that Little Warsaw’s cultural politics fit the European theoretical and artistic trends; at the same time their works mostly reflect the local quasi-national traditions of Hungarian art.) If there was really an international or even post-national standard, then I think Csaba Uglár would have received the prize. For me, his Arrival of the Furnitures and Kaszás’s Conference of the Plants were the most convincing. Actually, Uglár has been prolifically practicing criticism and subversion for almost fifteen years, but probably he did so in such a non-conformist manner that it has never yielded him as much as a Munkácsy Prize, let alone a grand international biennial.

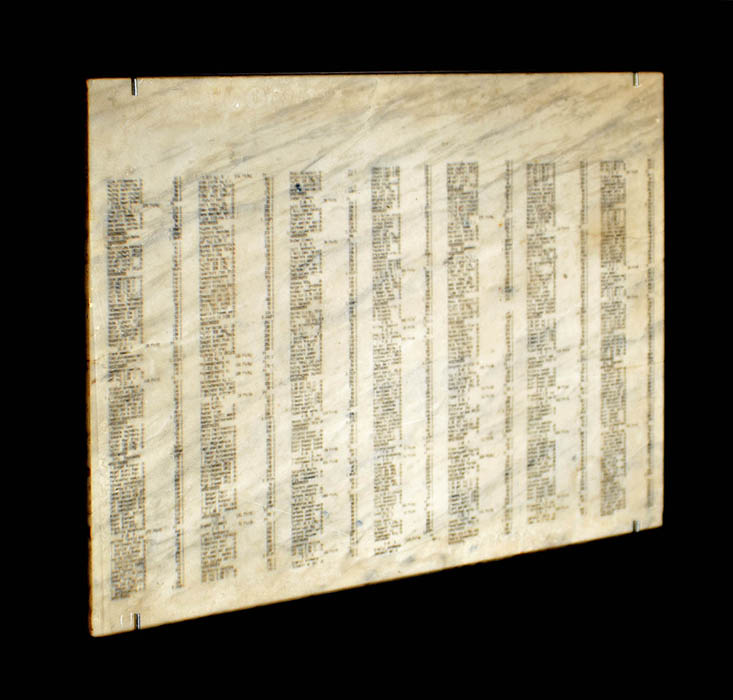

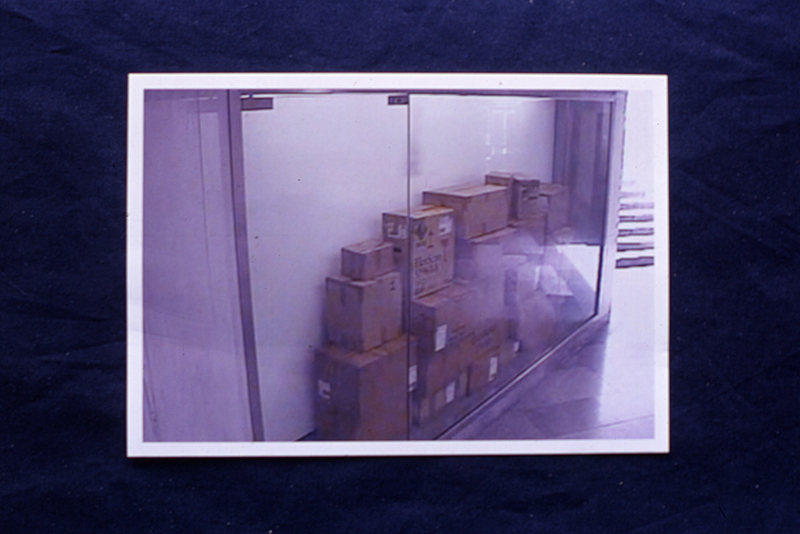

The problem may be that Uglár paints, which is not something a critical artist should be doing today. But even if we look at it from this perspective, Uglár doesn’t even paint that much! When he does paint, what he creates is often tricky. His untitled black paintings (1996), which have ball bearings added to the pigment, not only evoke such non-medium specific entities as the universe or heavy industry, they also criticize radical medium-specific painting while being at the same time its best (Hungarian) representatives. Uglár’s Arrival of the Furniture-a paraphrase of the panorama Arrival of the Hungarians, depicting seven legendary chieftains as they enter the Carpathian Basin in order to settle-is an excellent work both politically and aesthetically, calling to mind the cultural centers adorned with socialist panoramic murals. Courtesy of the Irokéz Collection much of Uglár’s oeuvre has recently been on display. His sculpture Hairy Girl and the installation Losers and Beautiful People (slot machines combined with solarium tubes) mark the frontiers of medium-conscious capitalist art vis-à-vis the abject and pop. In the meantime, a less widely known film and installation by the artist is entitled Abuse. The title is meant to evoke the Buddhist monasteries, the Ukrainian mafia, terrorism, the mass media, and obsessive self-documentation and deals with what film can do in art: it can convey ideals, record events, define capitalist culture in theory and practice. In terms of anti-capitalism and the post-Marxist subject,Uglár’s Monument to the Unknown Shopper (a supermarket receipt projected onto a marble plate) is a worthy match for Csákány’s The Worker of Tomorrow. The paradox of what Jacques Rancière calls the aesthetic regime and its compulsive autonomy is even more markedly manifested in Csákány, although both works go toshow that aesthetics and politics not only intertwine subtly and rhizomatically, but also elicit continuous reflection on the part of critical artists.(Jacques Rancière, Le Partage du sensible. Esthétique et politique (Fabrique, Paris, 2000).)