Markéta Othová (Online Gallery)

BIO | GALLERY | EXHIBITIONS | ARTIST’S STATEMENT | CRITICAL APPRAISAL

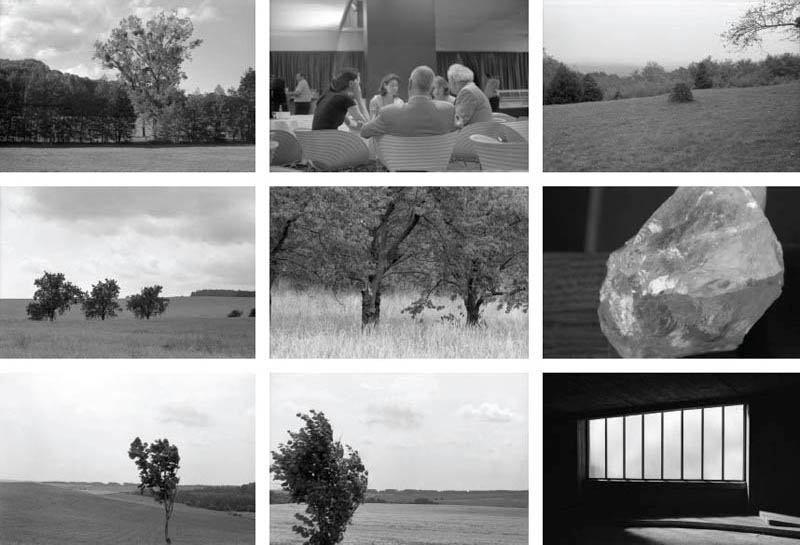

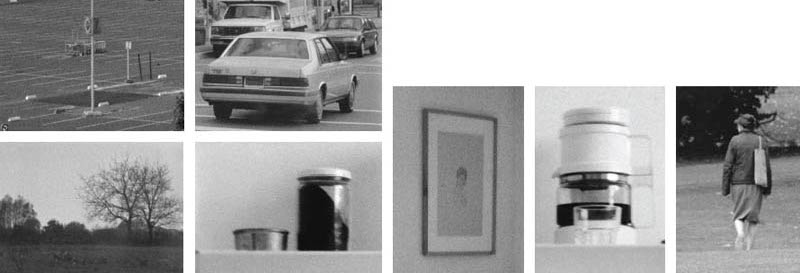

ARTMargins is pleased to show a series of recent photographs by Markéta Othová. Othová studied at the University of Applied Arts in Prague. She has worked with photography since the early 1990s and lives and works in Prague. Her work reflects the strong Czech tradition of avant-garde photography, yet she does not follow that tradition blindly. Othová’s photographs are usually black and white, large-scale, and informed by a strong emphasis on structuralrelationships. This emphasis on relational structure contrasts with the seemingly casual subject matter of her photographs – interiors, street scenes, landscapes, and still lifes. Low in resolution, unframed and pinned to the wall, her images are often arranged in series and divided into groups of corresponding photographs. Literature, music, and film inform Othová’s work as much as the history of photography itself, and in some of her recent works she has been concerned, in particular, with the temporal aspects of photography. For instance, Return (Návrat) (2000), a series of 12 photographs, captures a woman walking her dog up and down a suburban street. In Utopia (2000), a group of children play seemingly undisturbed next to a building. Othová has exhibited at various national and international venues.

EXHIBITIONS

2009 The oldest Art of Centrale Europe, NF Gallery, Ústí nad Labem

2008 Hiya Nan, Divus Unit 30, London

2007 You don’t know me, but I know you, Mücsarnok Kunsthalle Budapest

Leçon de photographie, Nicolass Krupp Gallery, Basel

Mayday, Josef Sudek Studio, Prague

2006 Talk to Her, Jiri Svestka Gallery, Prague

Pardon?, The Photographers’ Gallery, London

2005 Belongings, Place, Adriena Šimotová, Markéta Othová, Caesar Gallery, Olomouc

Emergent View, with Michal P?chou?ek, Die Kommunale Galerie im Leinwandhaus,

Frankfurt am Main

2004 L’ île de la tentation, Nicolas Krupp Gallery, Basel

Markéta Othová und Yoshimoto Nara – Fotografien, Neues Museum Nürnberg (from

NMN Collection)

A Good Idea, with Ivan Vosecký, NoD. Roxy Gallery, Prague

2003 Next Year in Marienbad…, with Ján Man?uška, Czech Centre New York

Best of, Jiri Svestka Gallery, Prague

2002 Different Voices, ?eské Budzojvice House of Arts

2001 French Connection, Pierre Daguin, Markéta Othová, Czech Centre Gallery,

London

While You Were Sleeping, Czech Front Gallery, Los Angeles

Utopia, Nicolas Krupp Gallery, Basel

2000 Claudio Moser, Markéta Othová, Kunsthalle Basel

1999 Power of Destiny, Moravian Gallery Brno, Pražák Palace

1998 A Perfect World, Institute of Contemporary Art, Dunaújváros

Her Life, The National Gallery in Prague, Veletržní Palace

Team Spirit, Pierre Daguin, Markéta Othová, Václav Špála Gallery, Prague

1997 Fire for Pockets!, The Brno House of Arts

A Perfect World, Gallery Alain Gutharc, Paris

1996 Apollo 13, Pierre Daguin, Markéta Othová, Ruce Gallery, Prague

Old Sources, The Prague City Gallery, Old Town Hall, Prague

1994 Other Weapons, British Council, Window Gallery, Prague

ARTIST’S STATEMENT

I have been taking photographs since 1986, thanks to a school assignment I had to do, and I exhibited my first set of photographs in 1994. For this I chose the largest format (110×160), which was determined by the width of a roll of photographic paper, as I wanted to force photography to cease being an object and to becomean image. From then on I took pictures of lots of things, more or less all the time. I would archive these images, and after a while I would go back and select some to create various sets—a style I worked in for years, up until about 2004. At the beginning I saw my unwillingness to concern myself with the formal aspects of photography — all I wanted to do was deal with the contents of the series – as an advantage. However, gradually this turned into an obstacle. I overcame this format by making cut-outs from finished blow-ups. While I continued applying this method, I began to think about the means of photography itself. This was a digression from journal-like testimony (even though I didn’t perceive it as such at the time) and a move towards attempts to process something that was set beforehand, or at least towards a desire to do something of the kind. This method yields both great uncertainty as well as pleasure, and in this I have been dwelling.

(Translation from Czech by V?ra Chase)

CRITICAL APPRAISAL

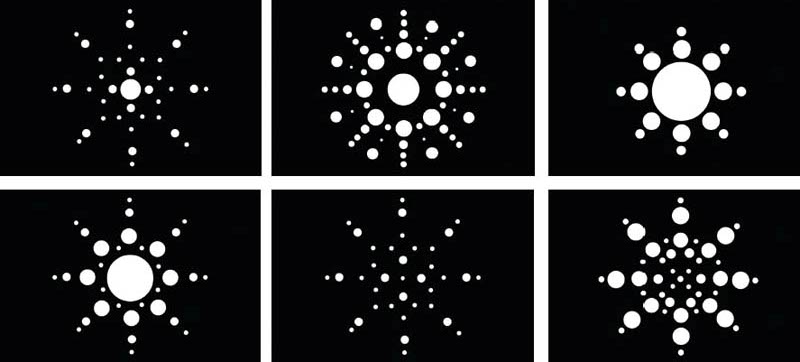

The movement inscribed into Markéta Othová’s works evokes an instinctive descent through the history of photography. Her point of departure has turned out to be the 1990s “archival turn”: beginning in 1994, the artist started to mine an extensive archive of her own snapshots, made primarily during trips abroad, putting together photographic installations of such a nature that the significance of the particular pictures was specified only by the syntax of the whole. Towards the end of the decade, Othová then shifted to the technique of temporal series, recorded sequentially – which put her close to the use of photography as we know it from 1970s Conceptual Art. And in her latest works, she is more focused than ever on the composition of particular images, now shot (in clear contrast to her previous cycles) exclusively in the lab environment of a photographer’s studio – so that, in her trajectory through the history of photography, she has now arrived at the experiments of the photographic avant-garde from the 1920s and 1930s: similar to the avant-garde’s representatives, Othová is also questioning the very nature of the photographic medium and the stability of the visual world.

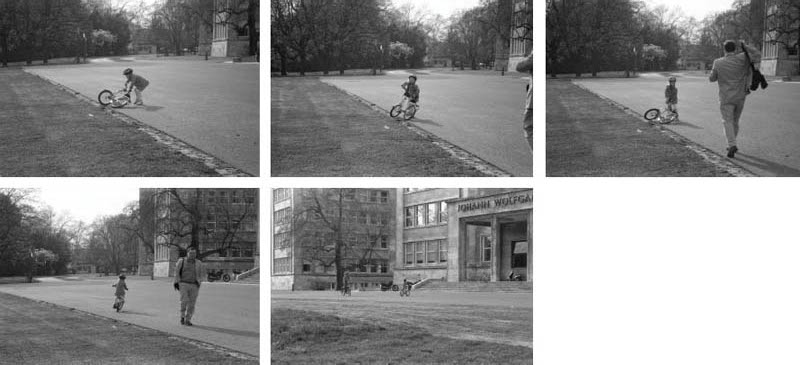

Even though the Untitled cycle of 2005 was made just as mechanically as Return, their respective orientation is different. There are only five shots here, each of which, however, represents a completed stage in the overall development. The first four images were taken from an almost identical position. First, a small girl lifts a bike from the ground; second, she is looking straight at a man who enters the image from the right; third, the man approaches her and the little girl stops trying to lift the bike; fourth, each protagonist leaves in another direction. From a broader viewpoint, presented by the fifth shot, we see the little girl turning to an older girl who is riding by. The series captures a clash of the child’s “small world” with the “big world” of the adult. However, it does so only indirectly, as the final montage omits the clash itself, concealing it in the temporal and spatial gap between shots no. 3 and no. 4, only confronting us with the result of the encounter: each figure going their own way. Whereas the little girl goes where she wants, the man, who was in a rush at first, goes back slowly, as visible in image no. 4, with his hands in his pockets.

Untitled thematises the reversibility of montage and de-montage. Initially, continuous action has been decomposed into static shots; thereafter, it is recomposed into a phased sequence. However, the resulting series is inscribed with the dual power of de-montage: not only a source of knowledge, but also the cause of destruction of the decomposed thing or action. While it is certainly possible to decompose the entire situation and analyse it step-by-step, the essential recedes in an irretrievable fragmentariness. The mischievous ambivalence of de-montage is a privilege of the “small world” of the child, for it is capable both of reviving dead things in play and of destroying them to explore their parts. The “small world” of the child is not enclosed in the “big world” of the adult. It is not as if the girl’s movements were enchained on the basis of any rational cuts that would link them in a natural way.(Cf. Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2: The Time-Image, translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta, London: The Athlone Press 1989, pp. 270–279.) Her motion implies no physical reaction – it remains a purely optical situation. All it does is link up with the view of an adult woman who has recorded the girl’s movements in her photographs. And from this adult woman’s perspective, it captures not only the continually passing present of a child, but also the cherished past of a childhood she lived through herself. Like a hidden self-portrait, the images from the “Untitled” cycle decompose into two simultaneous time currents that cannot be reduced to each other. Only through them can we be children and adults at the same time.

And a dialectical character of this kind need not be limited to a sequence of images; a single image may suffice. This is the case with the 2000 photograph Something I Can’t Remember that captures the interior of the living space in a functionalist villa in Prague’s Hodkovi?ky neighbourhood. Since the widow of the building’s first owner, the film director Martin Fri?, maintained the villa in its original state, Othová’s 2000 photograph presents us with a view from 1935, the year the mansion was finished. It is only through the forgotten cover of the camera’s lens that the present is embodied in the photograph. Cognitive scepticism, expressed by the title, is likewise referenced by the image’s blind spot – a painting, hanging on the opposite wall, that is made invisible by a reflex. The blind spot constitutes the signifying focus of the image – as is also shown by the liminally cropped table at the lower image border. In the photograph, the empty space of the interior is captured as a still life in which things, assembled in a fixed composition, become immersed in their silent life. A thing I can’t remember emerges in our view as a déj`a vu, a memory of the present that embraces both of the constitutive features of time, so that the actual present is also always a virtual past. Thus, even this single image is of a dialectical nature, since it assembles mutually unconnected and inherently divergent times.(In dialectical image, cf. Walter Benjamin, „Zentralpark”, in Gesammelte Schriften, vol. I, no. 2, Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp 1974; and Georges Didi-Huberman, Devant le temps: Histoire de l’art et anachronisme des images, Paris: Minuit 2000, pp. 85–155.)

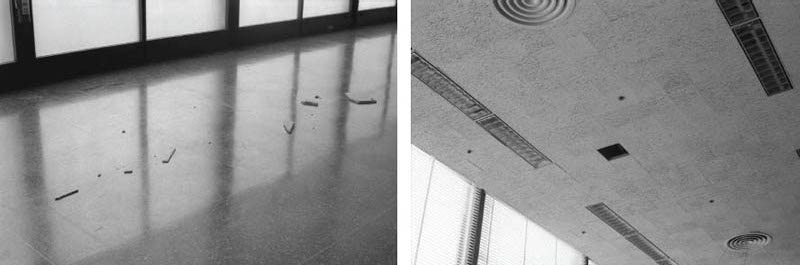

The complexity of every image is also explicitly thematised by the Untitled series of A4 cut-outs, made by Othová from her older photographs in the then-typical format (110 cm x 160 cm). The subject of the image – be it a parking lot, a landscape, a Chrysler, a drawing, a coffee-maker, or a woman in a park – is invariably focused at the centre of the photograph, whereas towards the frame the image becomes gradually neutralised so as to emphasise the manner in which it came into being. Besides the format and the strictly central focus, it is also the coarser grain of individual prints that testifies to the shared origin of these photographs. And its best evidence is their common temporal characteristics: “undated”. As physical cut-outs from photographic prints, these images do not capture an external, temporally determined reality. Rather than an interpretation of the represented reality, they are a severance thereof. Thus, indirectly, they also capture the photographic process itself as a mere framing of an already given configuration. The very reality of a world that is not inherently united is endowed with the nature of a sign. In advance, things themselves are permeated by photography.

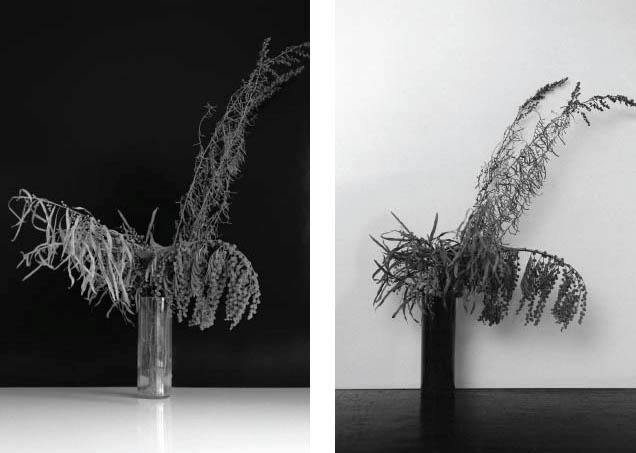

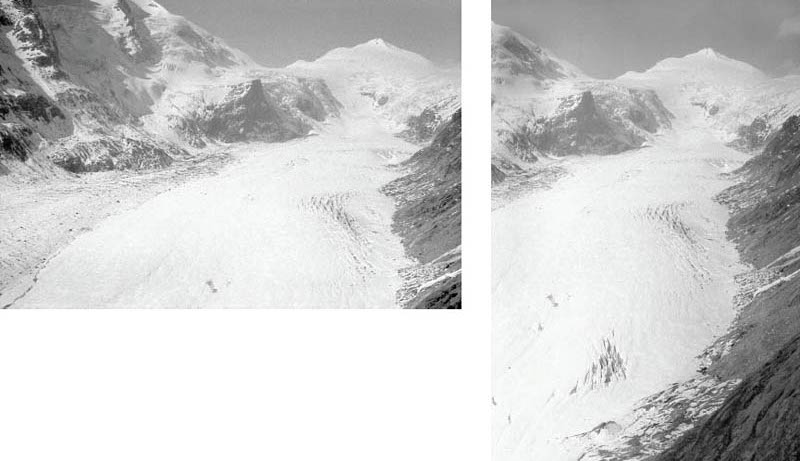

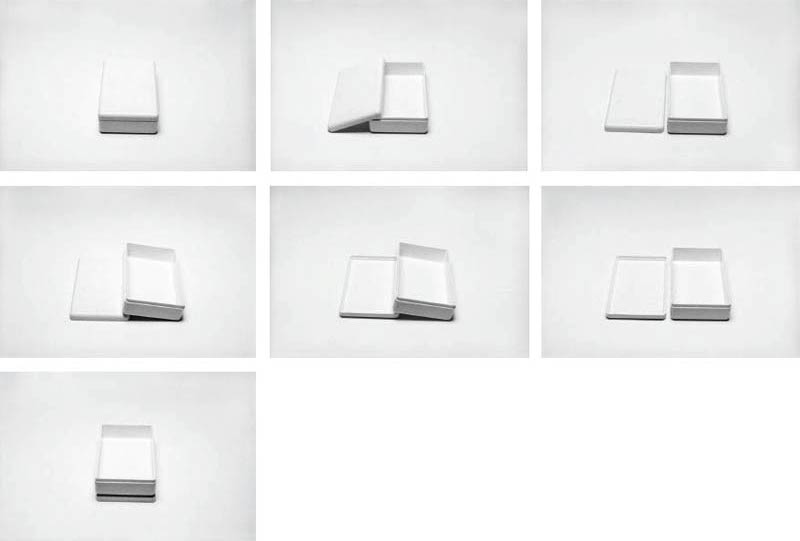

However, for a photograph, being indexical does not mean being faithful – as is clear from the pieces where, in her descent through the history of photography, Othová has come close to the experimental and reductive tendencies of the first decades of the 20th century. This is the case in the cycle Leçon de photographie from 2007, composed of seven pictures that depict a white box against white background. The colour of the captured object is no different from its surroundings, so that one would expect it to remain invisible – and yet it turns out to be set off by the shading that outlines its silhouette. Thus, we end up seeing the object in the photograph only due to the difference injected into it by photography. This is also made explicit in the Untitled diptych with a floral still life from 2008. Here, Othová has captured one and the same bunch of flowers, first against a dark and then against a light background, with the object thus being captured as light-coloured in the first photograph and dark-coloured in the second. Combined in a single installation, we will tend to consider these two independent images merely as a positive and a negative. Yet the stability of the visual world is most forcefully disrupted in another Untitled diptych, this time from 2000. Through repainting, Othová has linked two perfectly distinct photographs in such a way that we consider them identical. Othová has achieved this effect by means of a geometrically reductive repaint that leaves only a small cut-out in the middle of the first image – a segment that appears to fit into the blind spot in the second picture’s repaint.

— Karel Císa?

Reprinted with courtesy of Camera Austria, Graz, no. 106/2009, pp. 11–22.

(Translation from Czech: Martin Pokorný)