Andrey Kuzkin, Conceptualist Son (Series “New Critical Approaches”) (Article)

It does not take more than a fleeting glance at much of contemporary art practice to realize that Conceptual art is still with us. The similarities go beyond stylistic continuity. Conceptual art’s concern with fundamental questions of artistic meaning and interpretation has endowed art with an awareness of its own conditions and its relationship with a wide range of social life. Indeed, most art today is indebted to the efforts of Conceptual artists in the 1960s for breaking the spell of Greenbergian modernism and opening up a wider range of issues than had previously been accepted.

Russia experienced its own influential Conceptual art movement in the 1970s and 1980s, but the issues raised in that movement’s wake are slightly different from those of the Anglo-American context. Anglo-American Conceptual art set out to strip art to its essence, often to a linguistic proposition, a gesture with profound anti-institutional implications. In contrast, Conceptual art in Moscow gathered all the resources at its disposal to fashion the very institutions that it had been denied and outside of which it found itself in those decades. As Boris Groys has noted, Moscow’s Conceptual artists, like their Anglo-American counterparts, made extensive use of language, incorporating text within pictorial space and raising commentaries and descriptions of actions to the status of artworks.(Boris Groys, “Communist Conceptual Art,” in Total Enlightenment: Conceptual Art in Moscow, 1960–1990 (Madrid: Fundación Juan March; Frankfurt: Schirn Kunsthalle; Ostfilden: Hatje Cantz, 2008), 28–35.) However, aside from a few specific cases, Conceptual art in Moscow was not the radical project against visuality that had emerged in the mid-1960s in the Anglo-American milieu.

The subject of this article is an exhibition by the Moscow-based artist Andrey Kuzkin, entitled ZhZN, Everything I Wanted to Say but Found Myself Unable To, organized in winter 2008 by the late Olga Lopukhova at the ArtStrelka-projects gallery in Moscow. The installation, which served as the artist’s first solo show and received overwhelming attention and praise, made numerous explicit references to the history of Conceptual Art in that city. I examine the nature of Kuzkin’s appeals to this legacy and the attraction of such an artistic return in Moscow today.

Andrey Kuzkin (b.1979) came on the scene two years ago among a cohort of young practitioners working in a sometimes retrospective conceptual-poetic key. Their work has prompted comparisons to such heroes of Moscow Conceptual art as Ilya Kabakov, Viktor Pivovarov, and Andrei Monastyrski.(Among this cohort might be included Haim Sokol, MishMash (the duo Mikhail Leykin and Maria Sumnina), Irina Shteinberg, Natasha Zintsova, Andrey Malyshkin, and others.) In the short time since then, Kuzkin has worked in a variety of modes, staging performances and producing drawings, objects that are transformed in the course of a journey or encounter, and projects that inhabit a gallery space or register its history. His installation at ARTStrelka-projects, ZhZN—the Russian word for “life” with vowels left out—brought together all of these strands and quickly made Kuzkin a household name.(The abbreviation also brings to mind ZhZL, Zhizn’ zamechatel’nykh liudei (The Lives of Remarkable People), a series of popular biography books.)

ZhZN opened on January 31, 2008 in two large rooms of the ARTStrelka cultural center. On entering the space, viewers encountered dozens of planchettes—a common Soviet-era art material made of sheets of paper fastened to cardboard—arranged to lean against the walls, either directly on the floor or on low wooden shelves around the rooms’ perimeters. Books, small toys, and pieces of dusty electronic equipment were tucked into corners, conjuring the feel of an artist’s studio. Meanwhile, Kuzkin himself lay curled up beneath a blanket, turned to the wall and with his slippers and a collection plate on the floor below.

In one room, a wooden trunk was piled with sheets of fine-art paper containing scribbles and messages that viewers could leaf through at their leisure. (A sign requested that they not be taken, promising that the artist would be happy to give them away after the show.) Near the entrance of the first room, a reception table was heaped with plastic cups and bottles of multi-colored liquids labeled “boiled oil,” “acetone,” or “urine,” but actually containing ordinary refreshments of wine, vodka, juice, and cola.(This part of the installation was entitled The Power of the Word.) A hand-made banner with the words “ALL THAT EXISTS IS MINE” was hung outside the gallery entrance.

Undoubtedly, the largest role in ZhZN was played by the gallery space itself, where the overstuffed walls and floors appeared to merge an artist’s private studio with the public spaces of artistic reception and potential commerce in a chaotic textual and tactile total installation. What’s more, the now defunct ARTStrelka-projects gallery, a not-for-profit exhibition space that had served as an important site for innovative projects and early-career shows in Moscow since 2004, endowed the show with instant credibility. Located adjacent to the Red October Candy Factory (home to the posh Baibakov Art Projects), and directly across the river from the opulent Church of Christ the Savior, ARTStrelka was considered among the city’s last truly successful holdouts against the spread of commerce into contemporary art.

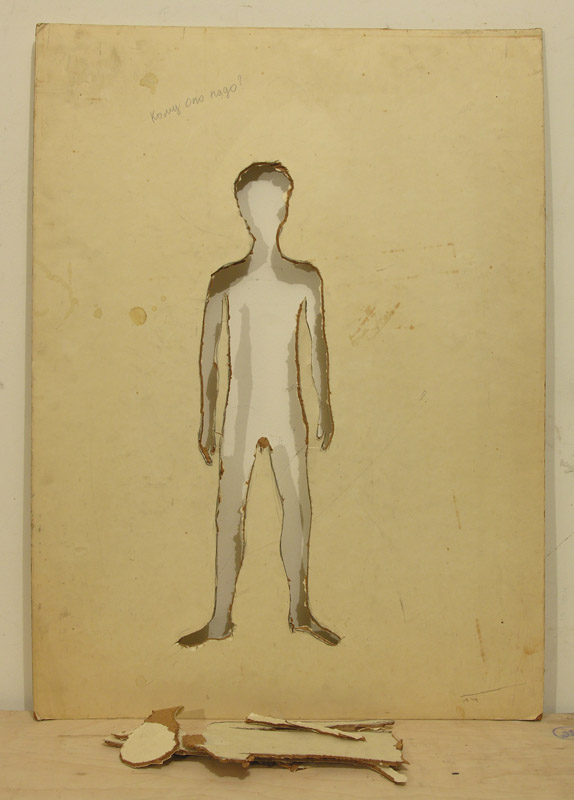

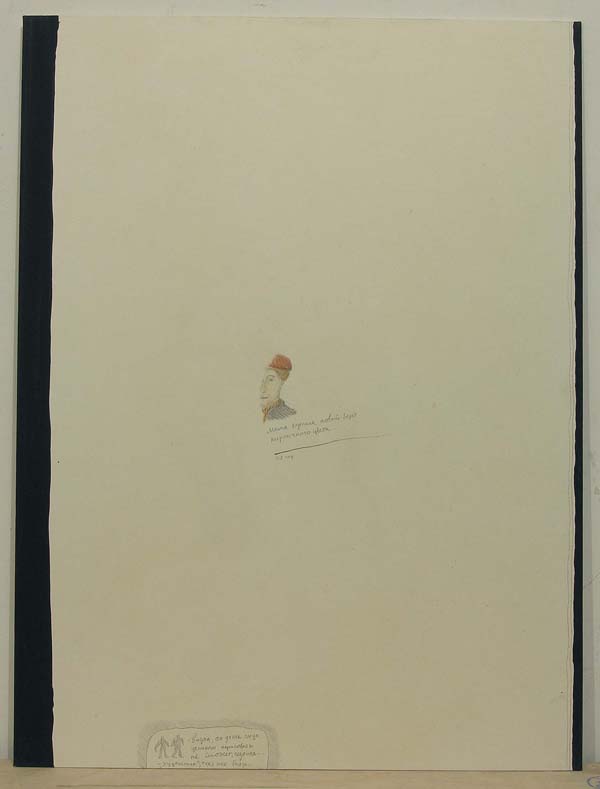

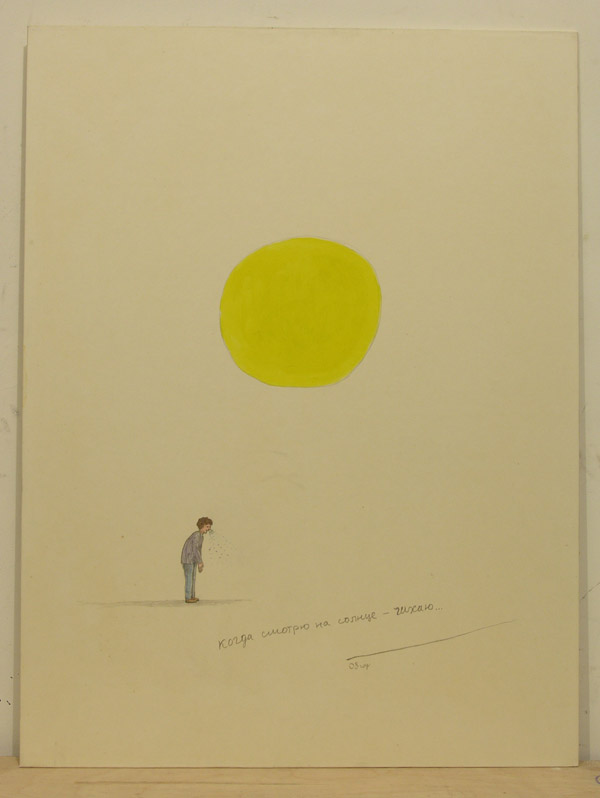

The ZhZN installation alluded to the legacy of Conceptual art in Moscow both explicitly and in more subtle ways. One work (Who Needs It?, 2008), a white planchette with the cut-out silhouette of a man in the center, recalls the missing-artist character from Kabakov’s installation The Man Who Flew into His Picture (1981–88; Museum of Modern Art, New York). Two others, Mother Bought a New Brick-Red Beret (2008), a simple drawing of a woman’s face above the title caption, and I Sneeze When I Look at the Sun (2008), a child-like drawing of a sneezing figure below a giant yellow sun, echoed the spare, emotionally resonant images and texts of Pivovarov’s albums.

The ZhZN installation alluded to the legacy of Conceptual art in Moscow both explicitly and in more subtle ways. One work (Who Needs It?, 2008), a white planchette with the cut-out silhouette of a man in the center, recalls the missing-artist character from Kabakov’s installation The Man Who Flew into His Picture (1981–88; Museum of Modern Art, New York). Two others, Mother Bought a New Brick-Red Beret (2008), a simple drawing of a woman’s face above the title caption, and I Sneeze When I Look at the Sun (2008), a child-like drawing of a sneezing figure below a giant yellow sun, echoed the spare, emotionally resonant images and texts of Pivovarov’s albums.

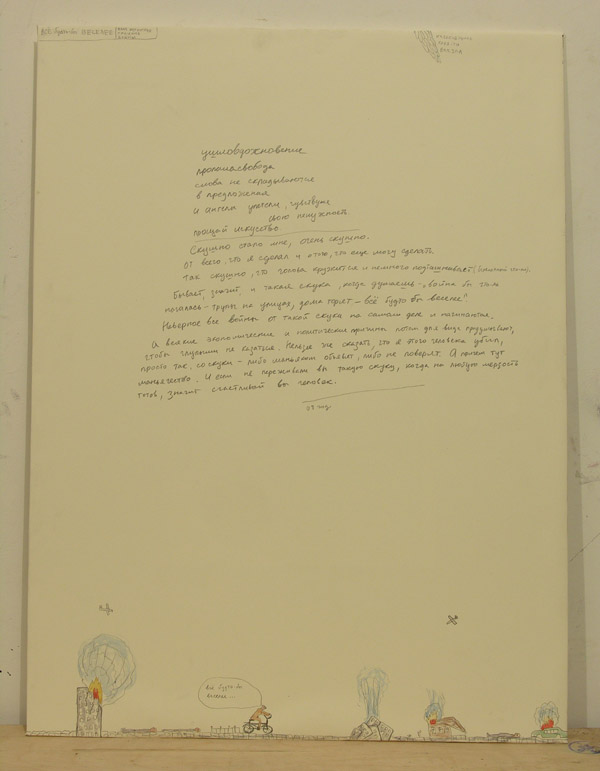

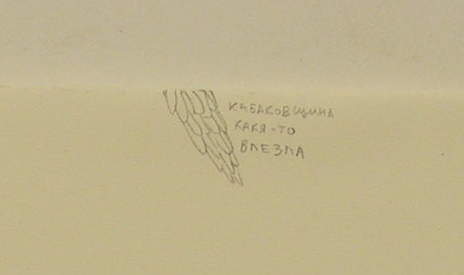

Arranged below eye-level, Kuzkin’s planchettes invite not so much lofty contemplation as casual perusal, as, for example, one might have leafed through artist albums in friends’ apartments in the 1970s. Such maudlin references, however, are not without a hint of irony in Kuzkin’s installation. As soon as one begins to recognize a familiar Conceptualist gambit, another work acknowledges the air of sentimentalism associated with such sources; a feathery angel’s wing in the corner of Everything Seems Merrier, or The Real Cause of War (2008) is qualified with the faux-apologetic quip, “some kind of Kabakoviana has gotten in.”(Compare, for example, to Kabakov’s Wings (How to make yourself better, or how to become an angel) (1999).)

Arranged below eye-level, Kuzkin’s planchettes invite not so much lofty contemplation as casual perusal, as, for example, one might have leafed through artist albums in friends’ apartments in the 1970s. Such maudlin references, however, are not without a hint of irony in Kuzkin’s installation. As soon as one begins to recognize a familiar Conceptualist gambit, another work acknowledges the air of sentimentalism associated with such sources; a feathery angel’s wing in the corner of Everything Seems Merrier, or The Real Cause of War (2008) is qualified with the faux-apologetic quip, “some kind of Kabakoviana has gotten in.”(Compare, for example, to Kabakov’s Wings (How to make yourself better, or how to become an angel) (1999).)

Kuzkin’s reprisal of tropes from Kabakov and Pivovarov, or his own father, Aleksandr Kuzkin—a graphic designer and artist who produced mail art and small, witty works on slips of paper—is both humorous and nostalgic, and demonstrates a fond respect for the tradition of Moscow Conceptualism, which itself developed over several generations of practitioners. From roughly the 1960s to the 1980s, art not explicitly in the service of the Soviet state maintained an underground existence. As a self-structuring network of artists and audiences, Conceptual art in Moscow (along with the alternative community more broadly) took on the institutional functions of galleries, collectors, and the critical press in the desire to shape the course of modern Russian art.

Unlike the generation of the 1960s, who fashioned their careers in Khrushchev’s Thaw and for whom public recognition was a meaningful goal, the Conceptualist generation of the 1970s did not, for the most part, protest its marginal status or actively seek to overturn the status quo. Moreover, without a market or museum structure that acknowledged non-state art, and with state institutions (book publishers, theaters, or television studios) often providing a source of income, the kind of institutional critique that became a trademark of Conceptual art in the West simply did not exist.

What did exist among the circle of Conceptual artists and poets, however, was a sustained tradition of dialogue and commentary between the members of the circle themselves that permeated the very structures of Conceptual art and poetry—what Lev Rubinshtein called “the art of relationships.”(Lev Rubinshtein, “Predvaritel’noe predislovie k opytu kontseptual’noi slovesnosti,” [Preliminary Forward to the Study of Conceptual Literature], Iskusstvo 1 (1990): 48; quoted in Bobrinskaya, “Moscow Conceptualism: Its Aesthetics and History,” in Total Enlightenment, 51.) The presence of such textual material in works like Kabakov’s Answers of the Experimental Group (1970–71), a painting juxtaposing several “ready-made” objects with statements by imaginary Soviet citizens, or the performances of the Collective Actions group, which often ended with group discussions, functioned as both artistic (specifically Conceptual) strategies and means of fostering a tradition outside of official institutional structures.(For Collective Actions materials, see Kollektivnye deistviia, Poezdki za gorod [Trips to the Countryside] (Moscow: Ad Marginem, 1998) and Kollektivnye deistviia, Poezdki za gorod, 6–11 (Vologda: Biblioteka kontseptual’noi shkoly, 2009).)

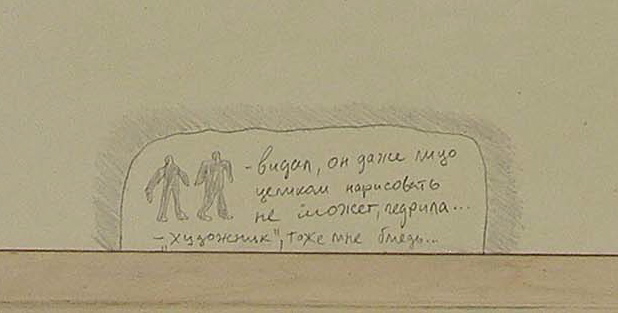

This point was not lost on Kuzkin, whose works adapt the “commentary from the audience” device to the conditions of artistic reception and criticism today. In this role, a pair of dark figures appears in the margins of various works through whom Kuzkin unleashes the voices not of Kabakov’s armchair philosopher, communal apartment dweller, or other late-Soviet types, but of the common philistine of Russia in the late-oughts. Thus below the portrait of Mother and her new beret, the two “art critics” let loose an obscenity-laced critique of the author’s drawing skills, calling into question his artistic credentials. In other works, the philistine-critics resurface to doubt the works’ sincerity, relevance, and worthiness of public exhibition space, and lament the absence of “anything sacred,” demanding that the artist be beaten.

This is the sort of comically vulgar, almost frighteningly hostile reactionary language one might expect to hear on a television reality show or a YouTube clip. Kuzkin’s deft use of the Conceptual trope of diegetic voices to anticipate the negative reactions of the hoi polloi (now amplified by the new modes of mass communication just mentioned) positions his own work as the offspring of late-Soviet Conceptual art. If the impassive voices of Kabakov’s experimental group staged an imaginary encounter between alternative art and a cross-section of late-Soviet audiences (still impossibly separate in the early 1970s), then Kuzkin’s farcical ones echo anxieties surrounding art’s present circulation in the public sphere, such as sincerity, criteria for judgment, and viewer hostility or misperception.

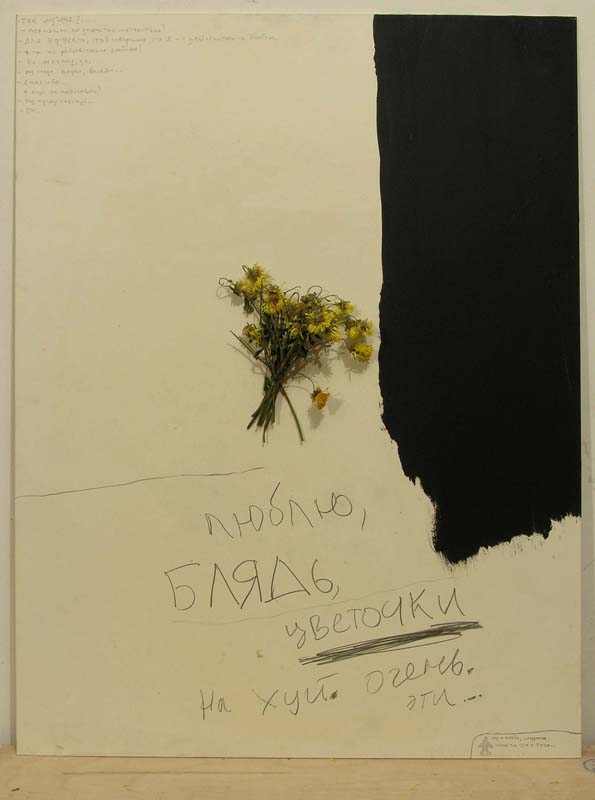

And yet, Kuzkin does not embrace the myth of the sincere vanguard artist, either. Instead, he mocks his own desire to be seen as such in Flowers (2008). A wilted bunch of dandelions hangs loose above the statement “DAMN, I love little flowers. Fuck. Like, a lot…” Immediately, another register of discourse materializes in the corner calling the statement into question. A voice asks the point of the obscenity. “For effect, so they believe me that I truly love them,” replies the artist-character.

And yet, Kuzkin does not embrace the myth of the sincere vanguard artist, either. Instead, he mocks his own desire to be seen as such in Flowers (2008). A wilted bunch of dandelions hangs loose above the statement “DAMN, I love little flowers. Fuck. Like, a lot…” Immediately, another register of discourse materializes in the corner calling the statement into question. A voice asks the point of the obscenity. “For effect, so they believe me that I truly love them,” replies the artist-character.

“But do you truly love them?” asks the voice.

“I think so, yes.”

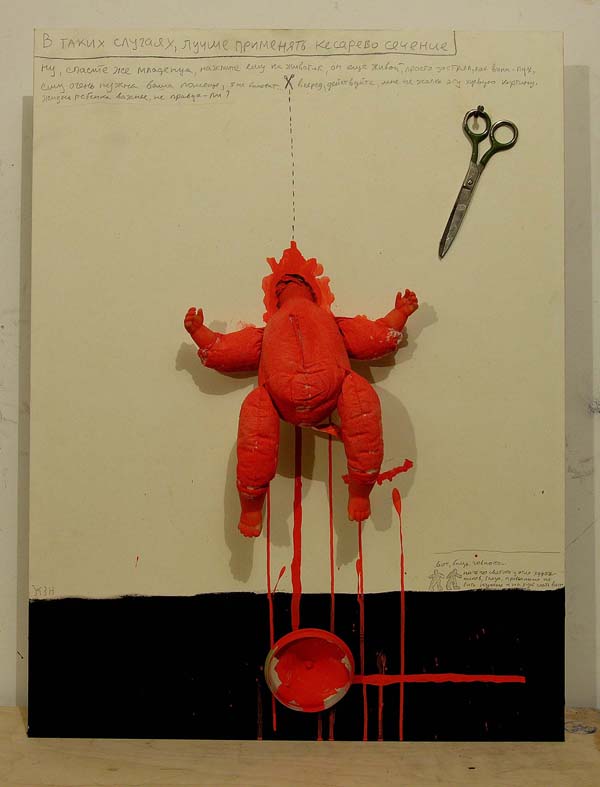

The ethical dimension of artistic production and consumption seems of particular concern in Kuzkin’s work. The work In Such Cases, It’s Better to Employ Caesarian Section (2008) announces it most urgently and farcically. There, below a dashed line and alongside a pair of scissors that hang on a nail like a Kabakovian tea kettle or vegetable grater, a paint-spattered baby-doll protrudes from a hole in the center of the picture, crying out “MAMA” when its belly is depressed. The text along the picture’s edge beseeches the viewer to disregard the artwork and act to save the baby’s life. If the ethics of late-Soviet Conceptual art were bound up in the deep social connections between its practitioners and audiences, then today, the work seems to say, these connections must be cultivated by the artworks and viewers themselves, within the public exhibition space. Yet while Caesarian Section, along with works like Flowers and Mother, seem skeptical about the capacity of Russian audiences to rise above regressive tastes and mindless consumption, they likewise mock the spectacle of an overt ethical imperative in art, staging it as the absurd choice between smelling flowers and saving children’s lives.

The ethical dimension of artistic production and consumption seems of particular concern in Kuzkin’s work. The work In Such Cases, It’s Better to Employ Caesarian Section (2008) announces it most urgently and farcically. There, below a dashed line and alongside a pair of scissors that hang on a nail like a Kabakovian tea kettle or vegetable grater, a paint-spattered baby-doll protrudes from a hole in the center of the picture, crying out “MAMA” when its belly is depressed. The text along the picture’s edge beseeches the viewer to disregard the artwork and act to save the baby’s life. If the ethics of late-Soviet Conceptual art were bound up in the deep social connections between its practitioners and audiences, then today, the work seems to say, these connections must be cultivated by the artworks and viewers themselves, within the public exhibition space. Yet while Caesarian Section, along with works like Flowers and Mother, seem skeptical about the capacity of Russian audiences to rise above regressive tastes and mindless consumption, they likewise mock the spectacle of an overt ethical imperative in art, staging it as the absurd choice between smelling flowers and saving children’s lives.

Against the institutional history of contemporary art in Moscow, Kuzkin’s performance of the homeless sleeping artist among the voices of his modest planchettes and ZhZN as a whole would seem to represent a nostalgic backward glance. If we trace this history from private studios and apartments, through the semi-public exhibitions of AptArt and KLAVA in the 1980s, the first galleries of the post-Soviet period, and finally to the more recent growth of the Russian art market, private patronage, and the proliferation of glamur (the term some use to denote glitzy, shallow, market-driven art), Kuzkin’s gesture appears to be a rejection of the present situation and a retreat into the private, underground spaces of three decades past. It is tempting, too, to see ARTStrelka itself as a relic of that time. It had a genuine, home-grown atmosphere, a thoughtful, loyal audience, and yet, despite its choice location, it wound up precarious, impermanent, and unable to resist the outside forces. It is a temptation that we should resist.

After nearly two decades of profound social, economic, and political changes, the history of Conceptual art in Moscow is still contested, its legacy unfixed. For young artists like Kuzkin, whose work is mediated by the institutional structures that have emerged since perestroika, issues of artistic legacy and the role played by public institutions can no longer be separated. This is why appeals to Moscow Conceptualist procedures today, despite that movement’s hermetic, originally non-public character, cannot but embody both of these concerns. Inevitably, it is these very appeals, the ways in which Conceptual art is figured in the work of Kuzkin and others, that subtly but surely come to write its history. It is for this reason that we must be cautious before making any conclusions about the meaning of Kuzkin’s allusive gestures, lest we end up resembling the jaundiced voices in the margins of his planchettes. To see his work as inherently backward-looking or nostalgic is to fail to consider the entirety of the situation; both Kuzkin’s citation of specific Conceptual practices and his own institutional location within a gallery in Moscow’s center. Rather than literally turning back on the development of artistic institutions in the last two decades, Kuzkin turns to the local history of Conceptual art and restages the encounter for the contemporary public. In this way, he avoids historicizing the recent past and instead performs what Nietzsche calls “critical history,” making the past useful for the present day.

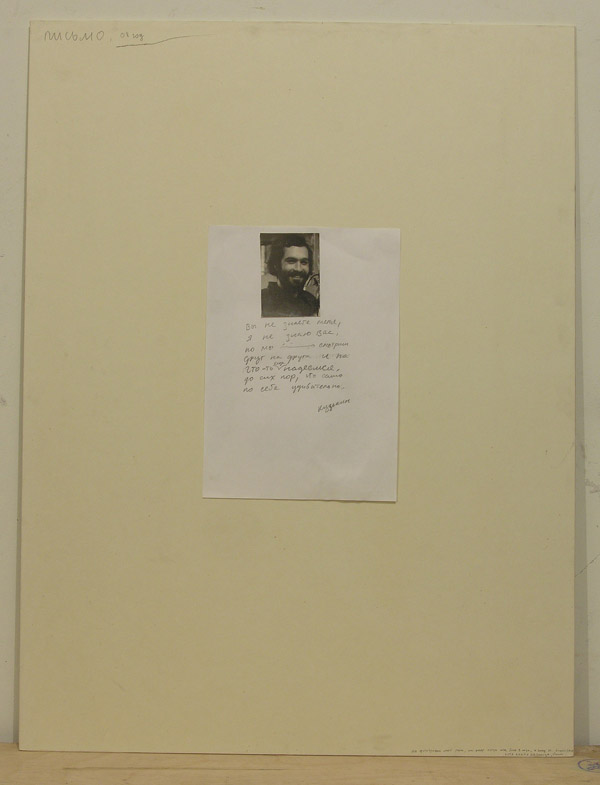

One work in particular, The Letter (2008), demonstrates this critical relationship of present to past in Kuzkin’s work. Below a picture of the artist’s father, himself an artist who died when Kuzkin was a young child, is an inscription reading “You do not know me, and I do not know you, but we look at each other and hope for something still, which is in itself extraordinary.” The second-person pronoun is the formal vy, suggesting that the words—be they from the elder Kuzkin or someone else—are addressed not the younger Kuzkin, as one might expect, but to the viewer in the gallery. In this way, Kuzkin avoids the easy path of staging an imaginary meeting between himself and the father he barely knew. Instead, personal history and the history of conceptual practice overflow their original sites and return from the past as voices of the future. While we cannot say that the legacy of Conceptual art in Moscow is univocal, the attempts to grapple with it today in the art of young artists like Kuzkin prove without a doubt that its strategies and traditions continue to pose questions to today’s “experimental groups.” gay lesbian movies list

One work in particular, The Letter (2008), demonstrates this critical relationship of present to past in Kuzkin’s work. Below a picture of the artist’s father, himself an artist who died when Kuzkin was a young child, is an inscription reading “You do not know me, and I do not know you, but we look at each other and hope for something still, which is in itself extraordinary.” The second-person pronoun is the formal vy, suggesting that the words—be they from the elder Kuzkin or someone else—are addressed not the younger Kuzkin, as one might expect, but to the viewer in the gallery. In this way, Kuzkin avoids the easy path of staging an imaginary meeting between himself and the father he barely knew. Instead, personal history and the history of conceptual practice overflow their original sites and return from the past as voices of the future. While we cannot say that the legacy of Conceptual art in Moscow is univocal, the attempts to grapple with it today in the art of young artists like Kuzkin prove without a doubt that its strategies and traditions continue to pose questions to today’s “experimental groups.” gay lesbian movies list

Further reading in the “New Critical Approaches” series:

Tanja Ostoji?’s Aesthetics of Affect and PostIdentity (Article) by Bojana Videkanic

Performatism in Contemporary Photography: Alina Kisina (Article) by Raoul Eshelman