Un-Doing Monoculture: Women Artists from the “Blind Spot of Europe” – the Former Yugoslavia

Since the 1970s, critical practices of women artists in the region of the former Yugoslavia have proven that these women are not only subjects to ideology imposed on them. Their works actively participate in politics of representation: by refuting simplified notions of self-representation, these artists contribute to the feminist critique of identity politics.

This paper deals with feminine (self)representations that challenge viewers’ expectations in many different ways. Specifically, I am interested in bringing into focus self-representations by the artists that deal with notions of feminine beauty and body image, as they are perceived in ideological and media environments of the specific cultures in Yugoslavia from the 1970 to the present.

Following the concept of un-doing monoculture, the artists I examine challenge hegemonic power structures – global as well as local. These artists successfully undermine at least two monocultures: first, ideologically oppressive, traditional Balkan, patriarchal, xenophobic monoculture; and second, dominant Western feminist monoculture. The insight into a specific region has, one should hope, an even more critical role in global context. Ironically, the continuing technological and communicational advances in our globalized present do not guarantee equal opportunities for all.

Instead of generating a “trans-national community with a shared set of aesthetic and perceptual foundations,”(J. Crary, in N. de Oliveira, N.Oxley, M. Petry, Installation Art in the New Millennium: The Empire of the Senses, New York: Thames & Hudson, 2003, p.i.) the art world remains structured as a set of multiple hegemonic systems. Situated on the margins of these power systems, practices by these women artists show repeatedly they are not belated reverberations of global trends; more often they are insightful and powerful critical practices in their own right.

Although critical interventions against what has been called “hegemonic feminism” – the Western brand of feminism that has dominated theory and art practice since the late 1960s – have recently appeared in feminist discourse, paradoxically, the practices of women artists from South-Eastern Europe (the former Yugoslavia) do not belong anywhere: neither to the developed (Western) European Union, nor to the so-called “Third World.”

At the same time, women artists from the region are widely represented on the global art world scenes in big international shows. Often, their work is instrumentalized to illustrate “belated feminism.” Impossible to interpret via binary oppositions – progressive vs. backwards, Eastern vs. Western, European vs. Exotic – this region is a true blind spot of Europe. In order to point to certain misconceptions in the West about artists from the region, my paper interprets works by artists from this region who have had an impact on the global art scene: Milica Tomic, Tanja Ostojic, Sanja Ivekovic, and Jelena Tomasevic.(Sanja Ivekovic (b.1949) and Marina Abramovic (b.1946) began their carriers in the 1970s and were both very much at the forefront of the most radical art of the time, and they are still active on the international art scene. Milica Tomic was born in 1960 and became internationally recognized in the 1990s, while Andrea Kuluncic, Tanja Ostojic, and Jelena Tomasevic, all born in the 1970’s, are producing art from late 1990’s until today.)

The Blind Spot of Ideology – The Serbian Body/European Body

The biggest republic in the former Yugoslav Federation (Socialist Federate Republic of Yugoslavia 1945-1991), Serbia and Montenegro is now a country in which part of the population desperately seeks entry into the European Union, while the other part is highly suspicious of the international community. The body of the nation feels the consequences of having chosen Slobodan Milosevic’s regime, mainly responsible for the civil war in the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s. Coincidentally, the body of the nation is now exhausted by ruthless economic transition from a ruined socialist model state economy to globalized late capitalism, which it does not and cannot fully comprehend.

Serbian artist Tanja Ostojic recreates Courbet’s iconic image L’Origine du monde (2002) by showing the European Union flag on her panties.

Thus, she denies the viewer’s gaze into her sex, pointing instead to another site of power – the emblematic yellow-star-circle. The artist stages Serbian inherent ambiguity towards Europe – its cultural supremacy and economic power. Ostojic, who belongs to the generation formed during the isolation of Serbia in the 1990s, uses different representational strategies than the body artists of the 1970s.

Thus, she denies the viewer’s gaze into her sex, pointing instead to another site of power – the emblematic yellow-star-circle. The artist stages Serbian inherent ambiguity towards Europe – its cultural supremacy and economic power. Ostojic, who belongs to the generation formed during the isolation of Serbia in the 1990s, uses different representational strategies than the body artists of the 1970s.

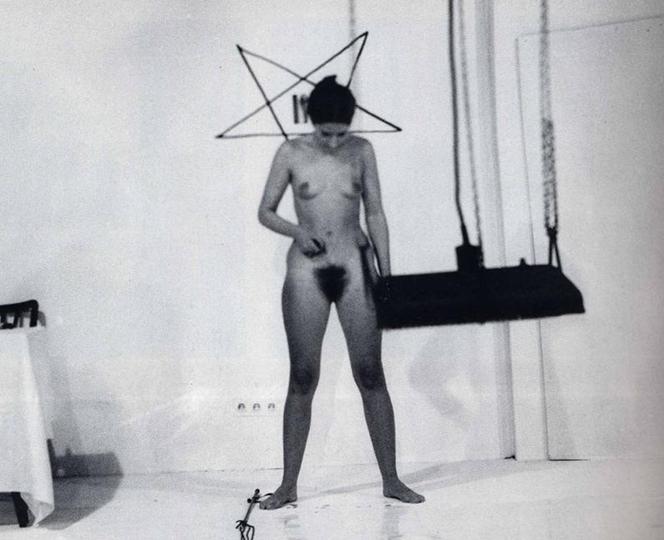

Pioneer performance artist Marina Abramovic, born in Belgrade, Serbia, carved a five-point communist star into her belly in her 1975 performance Thomas’ Lips.

Abramovic’s radical action emulated how ideology operates on the body of the individual. Thomas’ Lips’ ritualistic elements evoked the dramaturgy of a liturgical drama, or a passion play, by translating the eschatological dimension of the sacral into a subjective action. The artist consciously brought forward her own personal history, by using iconography both ideological and religious.

Abramovic’s radical action emulated how ideology operates on the body of the individual. Thomas’ Lips’ ritualistic elements evoked the dramaturgy of a liturgical drama, or a passion play, by translating the eschatological dimension of the sacral into a subjective action. The artist consciously brought forward her own personal history, by using iconography both ideological and religious.

Abramovic shows how ideology marks the body, and by making it so viscerally present, she points to the deepest layers of her own being.(Abramovic carved a communist five-point star into her own belly, and she suffered physical pain because of her own action.) By enacting this self-affliction, she complicates our perception precisely because it is a self-inflicted wound. Is she saying that, as a part of that socialist society, she willingly participated in its ideological rituals?

Ostojic, working some 30 years later, uses smoother representational operations – she points out to site of power by dressing up a socialist body in new garb. Finally, both bodies are marked by ideological signs: Abramovic’s with a communist star that made her bleed, Ostojic’s with European-Union luxurious panties – as a post-socialist belief in capitalist comfort.

The Post-Socialist Consumerist Body

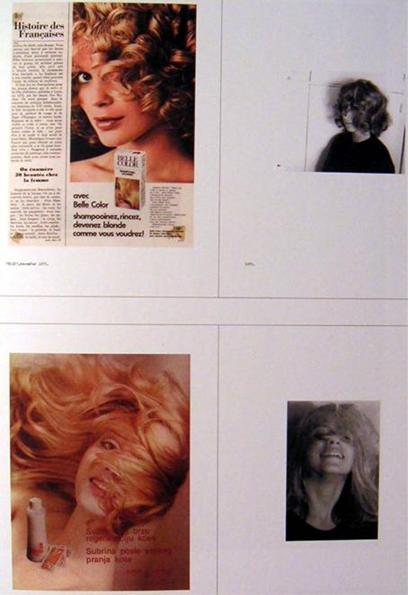

The Yugoslavian socialist government (1945-1991) practiced a strange combination of communist ideology with consumerist elements. As opposed to the countries under the Iron Curtain, Yugoslavian citizens could travel to the West and female citizens who were building a socialist, classless society could follow Western fashion trends. Croatian artist Sanja Ivekovic created a series Double Life in 1975 using fashion magazine advertisements juxtaposed with her private photos. She did not specifically pose for these in order to mimic magazine ads. However, Ivekovic had the intention of exposing fiction on both sides – the public and the private.(S. Eiblmayr, Personal Cuts, (exh.cat.), Vienna: Triton Verlag, 2001, p.14.) In the exhibition catalogue, Silvia Eiblmayr aptly observes:

The Yugoslavian socialist government (1945-1991) practiced a strange combination of communist ideology with consumerist elements. As opposed to the countries under the Iron Curtain, Yugoslavian citizens could travel to the West and female citizens who were building a socialist, classless society could follow Western fashion trends. Croatian artist Sanja Ivekovic created a series Double Life in 1975 using fashion magazine advertisements juxtaposed with her private photos. She did not specifically pose for these in order to mimic magazine ads. However, Ivekovic had the intention of exposing fiction on both sides – the public and the private.(S. Eiblmayr, Personal Cuts, (exh.cat.), Vienna: Triton Verlag, 2001, p.14.) In the exhibition catalogue, Silvia Eiblmayr aptly observes:

The subversive tactic of Double Life does not reside in the practice of provocation so common in the Seventies but quite the contrary (and here Ivekovic anticipates Cindy Sherman’s concept) by seemingly accommodating to the social codes and conventions of everyday life informed by mass culture. Yet precisely in the deliberate presentation of the reproduction, the repetition, the lack of an original, Ivekovic succeeds in breaking open the phantasm associated with the “pleasure of resemblance and repetition (which) produces both psychic assurance and political fetishization.(Ibid.)

By choosing images from her private photo albums, Ivekovic is not trying to comply with the magazine images, she is showing the artificiality of enhanced beauty, especially in cosmetic ads. Ivekovic’s photographs do not and cannot represent her like women in magazines are represented: she is smilingly subverting their truthfulness. The series convey the message: “this is how a pretty girl can look, without professional help (fashion photographer, make-up artist, stylist), and the ad is a fantasy.”

Only here, she is subverting the consumerist logic incorporated in the logic of the ad – she, Sanja Ivekovic, will not look any prettier if she buys and applies beauty products. She will not participate in this economy, since she knows better. She admits their seductive power – but does not let them faze her. Her own self-representations are not pathetic imitations of the fashionable perfected image, they are a cheerful counter-balance to its oppressive authority.(Ivekovic also does not follow early feminist suggestions that women should not enhance their looks – she does it consciously.) The series title “Double life” seems to suggest that it is not Ivekovic who is doubling fashion models, but that the site of authentic place of resistance resides within random snapshots from her life.(The title “Double life 1959-1975” suggests the span of her private photographs – the first one is taken in 1959.)

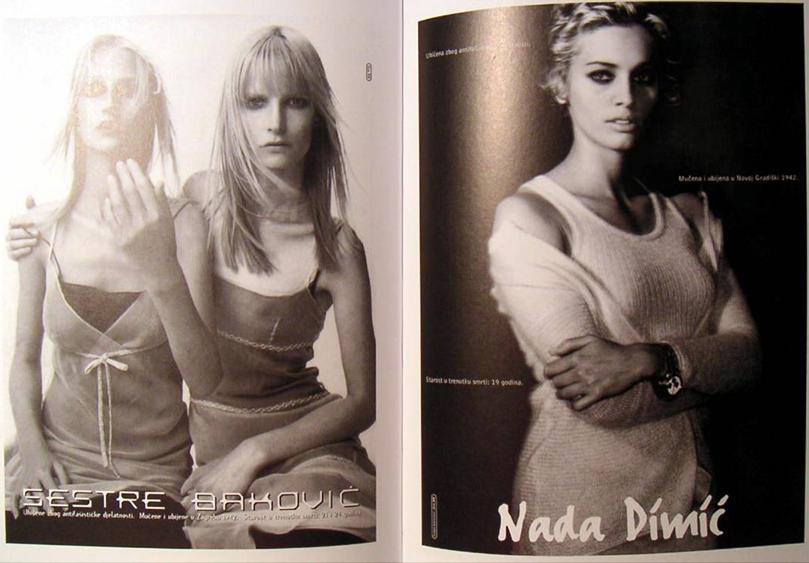

The debacle of communist ideology in the 1990s brought suspicion to all the elements of its heritage and marked the reign of the un-bound consumerism. In this context, Ivekovic relates “her critique of the politics of the visible as a driving force of consumer capitalism with the topos of the disappearance of the Socialist Republic of Yugoslavia by means of one of its mythic figures” – national heroines – “women who during the war were active in anti-fascist resistance, some at a very young, and were executed for this or driven to commit suicide.”(S. Eiblmayr, op.cit., p.15.)

In a series of appropriated fashion ads titled Gen XX (2000), the artist juxtaposes supermodels from contemporary fashion magazines with names and short texts describing how a particular heroine was killed.

Thus, the face of Linda Evangelista is “robbed of the messages attributed originally to her, namely to the logos of the company”(Ibid.) and now bears the name of the communist heroine: “Ljubica Gerovac, because of her anti-fascist activity was captured; during capture committed suicide; age at the time of death: 22.”(The text from the photo, see illustration, translated by J.S.)

Thus, the face of Linda Evangelista is “robbed of the messages attributed originally to her, namely to the logos of the company”(Ibid.) and now bears the name of the communist heroine: “Ljubica Gerovac, because of her anti-fascist activity was captured; during capture committed suicide; age at the time of death: 22.”(The text from the photo, see illustration, translated by J.S.)

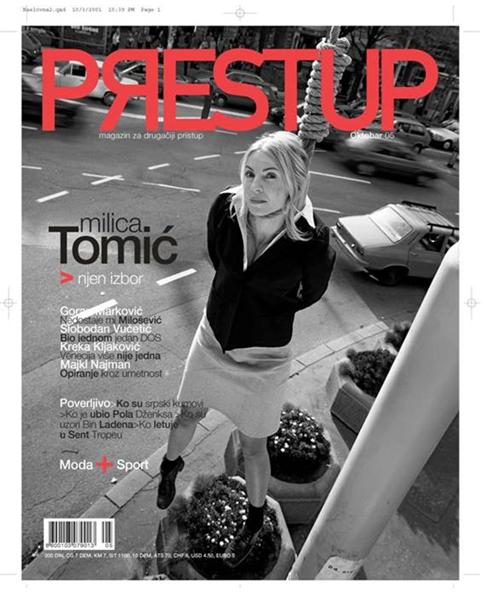

During the same period of post-socialist transition, Serbian artist Milica Tomic wanted to embody an anti-fascist resistance communist heroine herself. When asked by a typical post-socialist glossy lifestyle magazine to be photographed for a cover, she staged a photo of herself with title Belgrade Remembers (2001) on the Belgrade main street, hanging from a lamppost.

She evoked the anti-fascist resistance activists who were hung in 1941 by German troops, while Belgrade citizens were walking down the street not paying attention to the dead bodies hanging above their heads.(This interpretation of a historic event is purely anecdotal, as artist’s states, she heard it from her father’s friend. However, it is a historic fact that some people were hung in 1941 when Germans occupied Belgrade. See magazine “Prestup,” summer 2001.)

She evoked the anti-fascist resistance activists who were hung in 1941 by German troops, while Belgrade citizens were walking down the street not paying attention to the dead bodies hanging above their heads.(This interpretation of a historic event is purely anecdotal, as artist’s states, she heard it from her father’s friend. However, it is a historic fact that some people were hung in 1941 when Germans occupied Belgrade. See magazine “Prestup,” summer 2001.)

By inhabiting and appropriated the dying woman’s perspective, artist returns that disinterested gaze, and, in 2001, points to her own time. This is the time when both nations, Serbian and Croatian, built nationally-pure separate countries when Yugoslavia dissipated, and both renounced heritage of the anti-fascist resistance since it was closely linked to the communist past that the new regimes wanted to forget. Tomic invokes it purposely, in an act of resistance to collective amnesia. It can only be read as a critical comment on uncritical forgetfulness and ethical numbness of her fellow citizens.

Tomic’s seductive outfit can also be interpreted as a critique of the highly polished fashion photographs published in the same magazine of which she is on the cover. While her beauty can lure the viewer, the directed gaze of a hung woman will most probably deny pleasure. Tomic chose to speak from the position of the wound, from the “blind spot” of the dead.

Her dead heroine possesses the affectation of the made-up persona needed to be alluring on the cover of the magazine, making her transgression ever more visible. The presence of cleavage and her turning of the gaze right at the viewer signal the strategy of shifting power from a desirable model to the unbearable revenge of the victim.

Tomic continued to stage her persona as a “partisan” – a communist woman who fought against the Germans in the second World War. In different projects in Germany and Austria, she inserted her partisan heroine persona in different contexts that involve historic memory in today’s Western Europe.(“Secession Project” in Vienna – a poster in whish she, dressed in a partisan uniform, with a hat with a communist star, while riding in a Porsche, “thinks about overpopulation.” This project directly brings one discursive field of historic heritage of Yugoslavia to clash with the other – one of globalized, late capitalist Western world.) Tomic continued to stage her persona as a “partisan” – a communist woman who fought against the Germans in the second World War. In different projects in Germany and Austria, she inserted her partisan heroine persona in different contexts that involve historic memory in today’s Western Europe. In this project, she inserted her feminine presence (again, dressed as a partisan) between the statues of Russian and German soldiers, making a powerful statement about the fact that Yugoslavia lost more than 1.5 million people in the WWII and at least half of them were women.

The Body in Economic Transition

Croatian artist Andreja Kuluncic articulated feminine representation in the exhausting processes of transformation of state-run economy in late 1990s. Her project Nama (2000) named after the most famous chain of department stores in the country, dealt with the troubled repercussions of dealing with insolvent socialist enterprises in economic transition – stories of individual demise in social turmoil. Kuluncic created a poster with the actual Nama worker face on it, with the text “Nama: 1908 employees, 15 department stores,” placed in advertising spots throughout the Croatian capital Zagreb.

Croatian artist Andreja Kuluncic articulated feminine representation in the exhausting processes of transformation of state-run economy in late 1990s. Her project Nama (2000) named after the most famous chain of department stores in the country, dealt with the troubled repercussions of dealing with insolvent socialist enterprises in economic transition – stories of individual demise in social turmoil. Kuluncic created a poster with the actual Nama worker face on it, with the text “Nama: 1908 employees, 15 department stores,” placed in advertising spots throughout the Croatian capital Zagreb.

The poster presents a person “sentenced” on economic instability, while at the same time it suggests certain qualities such as trust, security and stability in typical advertising language. The project points to the fact that the Nama‘s problem is not isolated, recalling workers from various enterprises which went bankrupt in the period of transition.(The project is posted online: http://www.andreja.org/nama/exhibit.htm)

As the artist herself stated, having been moved by the media stories about the desperate situation of the predominately female workers who were left with no work, she organized a forum to open a dialogue of the position on workers in the new economy. The image of the worker on the poster should be read as a simulation – of a fantasy of a satisfied, dressed-up and made-up female worker, its goal was to empower ordinary women caught in history.

The Special-Effects Body

Milica Tomic’s widely shown and critically recognized video “I am Milica Tomic” (1998) questions the nature of national identity, and reflected the traumas of Serbia’s nationalistic euphoria of the 1990s.(The video was shown on The 8th Istanbul Biennale “Poetic Justice,” curated by Dan Cameron in 2003.) Tomic is clad in a white dress, symbolically linked to purity and religious ceremonies. Her stunning well-proportioned features and golden braid suggests a wholesome image of a white

Milica Tomic’s widely shown and critically recognized video “I am Milica Tomic” (1998) questions the nature of national identity, and reflected the traumas of Serbia’s nationalistic euphoria of the 1990s.(The video was shown on The 8th Istanbul Biennale “Poetic Justice,” curated by Dan Cameron in 2003.) Tomic is clad in a white dress, symbolically linked to purity and religious ceremonies. Her stunning well-proportioned features and golden braid suggests a wholesome image of a white

woman. As she makes clear, this is both a self-representation, while at the same time a representation of her heroine – “Milica Tomic.” Her striking beauty helped emphasizing the profound anxieties that follow feminine representation in contemporary art. Artists coming from not-so-First World are so often exoticized. If the artist is using her own, rather spectacular image, that can be so easily misread as exploitation. As national identity is so often constructed according to media representation of stereotypes, “I am Milica Tomic” argues precisely against this kind of stereotypical representation of national identity, by exaggerating and relativizing it.

Whenever Milica confesses a new identity in this video, she suffers – a new bloody wound opens on her body while she utters: “I am Milica Tomic, I am Dutch, I am Milica Tomic, I am Spanish” and so on, claiming different identities in circa 30 languages.(This is the number of the languages she could get instructions on pronunciations while she was working on the video in isolated Belgrade in 1998. Interview with the artist, August 2004.)

The installation dates from 1999 when Milosevic’s regime was in power, and just being Serbian was often perceived by the international community as a villainous act. That is why Milica (and her heroine) chose the world of special effects in which they can state their message – that they resist being found guilty only for belonging to a certain nation.(At the same time, the work was well received outside of Serbia, as Zdenka Badovinec explains in the catalogue of Arteast exhibition: Tomic denied to exist in Serbian context where the questioning of national identity was a wound in the nation’s healthy body. She could only speak openly from the position of the wound.) At the same time, artist shows her intimate identity, something she has not chosen for herself, is still part of her being and there is no point of simply giving it away. This is how she came to terms with it, using mediation and globalized means of mediation: digitized special effects. Mesmerizing is this sight of the wounding of a female body, dangerously exposed, yet superbly dignified.

Montenegrin artist Jelena Tomasevic, who, like Tomic lived through Serbian, and Montenegrin, nationalist paroxysms of the 1990s, represented her alter-ego, her rendering of a “national heroine” for the period of transition in her work titled “I heart Montenegro II” (2003). In this photograph, a corpse of a well-proportioned, model-like young woman, lies stiffly on her back in the woods. In a tight miniskirt, with her bare legs spread, and red-painted toe nails, her head is covered with a T-shirt emblazoned with words “I heart Montenegro” that serves only to deny the viewer a glimpse of the victim’s identity.

Again, as was the case with Tomic’s “heroine,” Tomasevic here willingly plays the victim. The created situation brings this photograph closer to performance territory, where the body-in-representation is also present. Tomasevic is present to demonstrate how national identity can be (literally) suffocating. The very title “I heart Montenegro” borrows the logo from and the slogan of the Italian brand Moschino (I heart Moschino) to bring into focus the fashion-obsessed consumerist culture that has been aggressively interjected in the country in the state of transition.(See S. Racanovic, Montenegrin Beauty, (exh.cat.), Budva, 2002, p. 54.) At the same time, a corps (which can be read as a sexualized life-size doll) brings into play the image of a woman-object in a drastically patriarchal society.

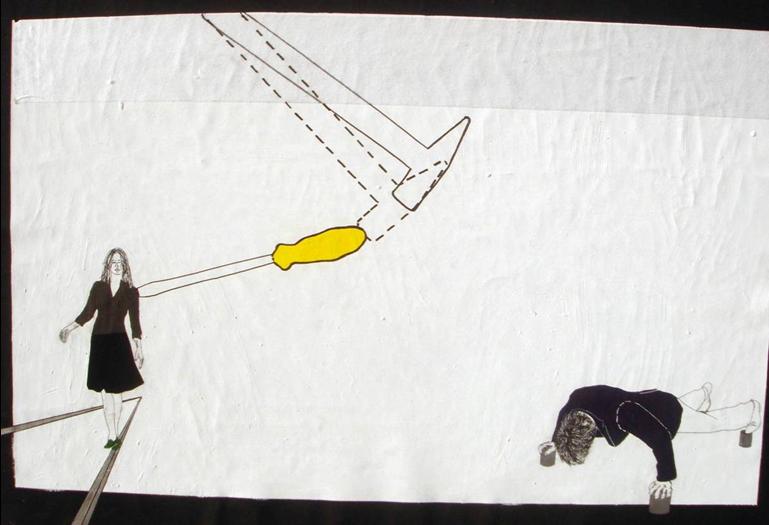

Tomasevic’s recent series of paintings titled “Joy of Life” (2004-5) represent female and male figures in disjointed time sequences within a white void of empty abstract spaces. All figures are visibly lacking any human emotions. They are actually not “real” representations: they are all replicas – copied from fashion magazines.

Tomasevic’s recent series of paintings titled “Joy of Life” (2004-5) represent female and male figures in disjointed time sequences within a white void of empty abstract spaces. All figures are visibly lacking any human emotions. They are actually not “real” representations: they are all replicas – copied from fashion magazines.

Thus, feminine representations are clad in stilettos and edgy outfits while engaged in strange, dream-like actions that suggest imminent violence. However, the perpetuator of the violent actions is never shown. In these ominous tableaux a woman in a little black dress is forced to her knees by a “mad” hair dryer.

Similarly, while the man’s head is about to be crushed with oversized pliers, a fashionably dressed woman is taking a photograph of the act. The representation reached here its zero degree, turning any possible empathy into a mediated spectacle. In the field of Tomasevic’s representations, the prevailing atmosphere of her protagonists’ blasé attitudes seem to mark the advent of the spectacle of late capitalism into Montenegrin wilderness.

Tanja Ostojic engages in critical actions of undoing racist and masculinist monoculture – within the context of economically and politically challenged, isolated art world of Serbia and Montenegro. In a recent performance project (2004), she created a “spiritual spa” for the Belgrade audience, in which she offered traditional Thai massage “to soothe the body of visitors” and a session with the artist “to calm their souls.” Playing upon the fact that Belgrade does not have any oriental spa salons, Ostojic uses a rather gentle (feminine) strategy to introduce another culture into a closed, xenophobic environment.

Ostojic also responds to the international art-world system of power relationships by staging web project series titled Strategies of Success: Vacation with a Curator (2002).

These photographs mimic the look of paparazzo tabloid photos of celebrities caught on the beach. She presents herself as a young, desirable, topless artist sunbathing with a male curator (who signifies the institutional bearer of power). Ostojic cynically implies that a female artist can succeed if she becomes involved with an influential curator who can help her succeed. The same critical stance was employed by Sanja Ivekovic as early as 1975, when the artist, following her practice of juxtaposing media images with her private ones, put together a photo of a celebrity and one of her own.

These photographs mimic the look of paparazzo tabloid photos of celebrities caught on the beach. She presents herself as a young, desirable, topless artist sunbathing with a male curator (who signifies the institutional bearer of power). Ostojic cynically implies that a female artist can succeed if she becomes involved with an influential curator who can help her succeed. The same critical stance was employed by Sanja Ivekovic as early as 1975, when the artist, following her practice of juxtaposing media images with her private ones, put together a photo of a celebrity and one of her own.

The title in a tabloid was ”She lost fifteen pounds” – and Ivekovic in the photo is showing how she lost weight, too. It is not accidental that this photo is chosen, as should it be read in the context of feminist critique of the dictated-by-media image of fashionable thinness that leads to success.

Post-historical Glamorous Body

Marina Abramovic recalls that in the 1970s it was necessary for a woman artist to dress like a man, and act rough, in order to be considered a serious artist: “If a woman artist would apply make up, or put on nail polish, she would not have been considered serious enough.” Only in the late 1980s, Abramovic, after splitting with her partner Ulay, decided to grow her hair long, and to wear high heels: she did not feel any longer the need to prove that she is tough, and she could “be what she considers she really is.”

It was then that she discovered “the desire for glamour.” Proscribed as merely a shiny surface that is itself a blind spot per se, glamour was banned from “serious” art. Now, it has returned, to expose that blind spot of (patriarchal) ideology can be fully illuminated through glamorous self-representations, as is the case with her new self-portrait Cleaning the Floor (2005).

It was then that she discovered “the desire for glamour.” Proscribed as merely a shiny surface that is itself a blind spot per se, glamour was banned from “serious” art. Now, it has returned, to expose that blind spot of (patriarchal) ideology can be fully illuminated through glamorous self-representations, as is the case with her new self-portrait Cleaning the Floor (2005).

Marina Abramovic also re-performed Thomas’ Lips as part of a series of performances titled Seven Easy Pieces at the Guggenheim Museum

in New York in November 2005. Re-performed 30 years later, this piece still had a powerful impact on the viewers: the artist showed that her communist heritage does not need to return as a traumatic memory. In her moving reenactment of the carving of the communist star, her own heritage stopped being a burden. It is what one cannot escape from, it makes one suffer, but, at the same time, empowers one to achieve authentic artistic existence.(Interview with the artist, November, 18, 2005.)

These women artists are indeed ‘self-positioned on borders,’ while constructing contemporary feminine identities in their cultures. Thus, exploring art practices at the southern and eastern boundaries of Europe that incorporate experiences of the disintegration of both the former Yugoslavia and the socialist project sheds light on the formation of feminine identities in the processes of fragmentation (“balkanization”). These practices also brought to attention the existence of manifold differences in feminine representations within larger European, and ultimately, global context.