Spirituality Is Embarrassing: On Zbigniew Libera

Zbigniew Libera belongs to Poland’s so-called lost generation of the 1980’s, to that generation whose most creative years fell with the barren and depressing time of Polish martial law. Added to the difficult socio-economic conditions were the philosophical and artistic crises brought about by the dominance of post-modernism with its confirmation of fragmentariness — a modern world no longer organized by any meta-narratives. This situation increased anxiety and fueled attempts at both the self-creation that would offer control of one’s own identity and the creation of private utopias. Within this fragmented world, it became necessary to ask the most primal questions about one’s own existence and spirituality. In his own way, by focusing his art on the basic processes of self-creation(It should be added that aestheticizing oneself and one’s own life was a paradoxical necessity in this kind of world, in which nothing was seemingly necessary. Nonetheless, in Libera’s art, this aestheticizing tendency had little to do with a fleeting, post-modernist faddishness of the 80’s (it was not “a dandy’s act of escape from the weakened social norms”), but it was more of a basic process of aestheticizing “the inner plasticity of the soul,” which is part of any human experience.), Libera has also responded to this challenge. His emphasis on a clearly metaphysical sense of one’s own singularity(Kierkegaard’s “truth of what is singular.”) and individual life energy, entangled in the “reality of influence,”(One of Libera’s favorite philosophers was Heidegger with his concept of a radical conditioning (“being thrown in”) of the self by the context of being.) is crucial to Libera’s art in the 80’s.

Zbigniew Libera belongs to Poland’s so-called lost generation of the 1980’s, to that generation whose most creative years fell with the barren and depressing time of Polish martial law. Added to the difficult socio-economic conditions were the philosophical and artistic crises brought about by the dominance of post-modernism with its confirmation of fragmentariness — a modern world no longer organized by any meta-narratives. This situation increased anxiety and fueled attempts at both the self-creation that would offer control of one’s own identity and the creation of private utopias. Within this fragmented world, it became necessary to ask the most primal questions about one’s own existence and spirituality. In his own way, by focusing his art on the basic processes of self-creation(It should be added that aestheticizing oneself and one’s own life was a paradoxical necessity in this kind of world, in which nothing was seemingly necessary. Nonetheless, in Libera’s art, this aestheticizing tendency had little to do with a fleeting, post-modernist faddishness of the 80’s (it was not “a dandy’s act of escape from the weakened social norms”), but it was more of a basic process of aestheticizing “the inner plasticity of the soul,” which is part of any human experience.), Libera has also responded to this challenge. His emphasis on a clearly metaphysical sense of one’s own singularity(Kierkegaard’s “truth of what is singular.”) and individual life energy, entangled in the “reality of influence,”(One of Libera’s favorite philosophers was Heidegger with his concept of a radical conditioning (“being thrown in”) of the self by the context of being.) is crucial to Libera’s art in the 80’s.

Libera started his artistic journey in 1981/1982, within that time period (beginning with the euphoria of Solidarity and ending with the depression of martial law) when “more interesting” things were happening in public spaces than in art galleries. The artist actively participated in these historic changes. Right after martial law was introduced (December 1981), in an act of “civil disobedience,” Libera began to design and print leaflets and posters protesting the army’smassacre in the Wujek coal mine. The iconography of Libera’s posters follows the models created in Paris during the students’ and workers’ protests of 1968.(The poster featured a ZOMO (military police) policeman’s head in a helmet as he was biting through an anchor with his huge teeth.) He plasters posters on walls in various cities. He also begins printing leaflets for Solidarity. Young and idealistic, Libera is convinced that, moved by the news of martial law, people would mobilize, protest, and overthrow the regime. The artist will be very disappointed to observe, in contrast, their mass conformity, acceptance of repressions, reification, and agreement to governance by force.(It’s worth mentioning that Libera began his career with decorating stores.)

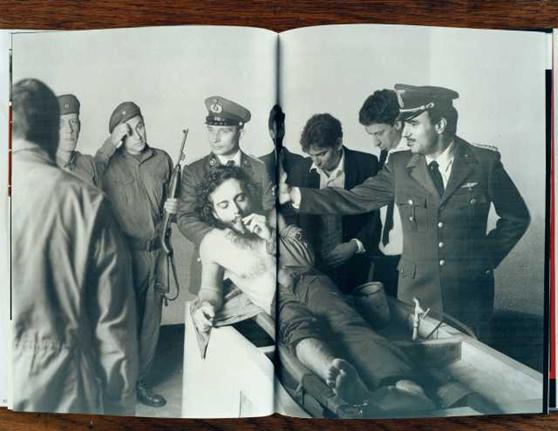

1982 was a crucial year in Libera’s “existential adventure”, generating a whole spectrum of radical feelings and psychological states. It began with his active participation in “the resistance movement”. It should be emphasized, however, that this participation was an expression of the artist’s individual protest, which simply got coordinated with the mass resistance of Solidarity. In the spring, Libera opened his first solo exhibition at Strych (The Attic) in Lódz. That fall, he was arrested by the secret police for designing, printing, and distributing anti-regime leaflets and posters. Following the speedy trial typical for these times, the artist was sentenced to a year and a half in prison. Although Libera received a political prisoner’s status, for the first half a year he was detained in the prison for “regular” criminals. Holding the twenty-two year old Libera, a young and sensitive artist, for many months in the same cell with real criminals (including thieves and murderers), exposing him to their unbearable and permanent physical closeness (he had to observe and listen to their conversations, behaviors, and physiology) brought about Libera’s permanent awareness of the ongoing potential for both physical (assault and rape) and psychological harm. The artist was in a constant state of anxiety about his ability to lead a normal life after his release. In order to survive, Libera had to learn “the language” of prison; he had to use it, and by using it he allowed himself to be corrupted and poisoned by it. In order to minimize its destructive (determining) influence he engaged in a game with this world. In prison, in this “reality of de-humanized language,” one had to have a deliberate defense strategy for those external “influences” that constituted the threats of reification, of becoming an object (non-self), and of death.

The artist was regularly trying to unmask, control and become conscious of how this institution was forming, reifying him, and irrevocably changing him.(The artist is gradually becoming fully aware of the need to work on himself, because “nothing simply just exists.”) The tenuous position of the self in this situation amplified Libera’s insecurity, his awareness of his own weakness, fantasies of power, “fear and terror,” and a whole spectrum of extreme and radical spiritual feelings that only intensify when confronted with a “cold,” rational world deprived of any metaphysical dimension. This spiritual dimension of his individual experience in the world has always been very important to Libera.(The artist has actually mentioned in his CV that he was a student at the Pallottine School. Whether it is true or not, for many years, Libera wanted this fact to characterize his biography, his existential and artistic journey.)

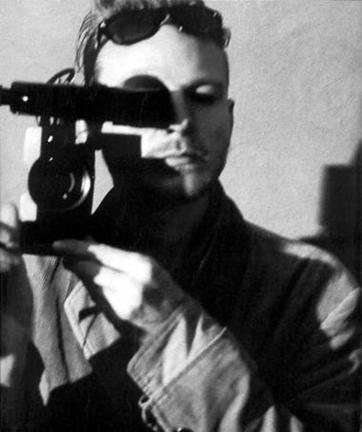

This “painful situation of the self” remained (though diminished) after the artist was freed from prison(In prison, he occupies himself making tattoos, hats, scarves, and drawings. After being moved to the prison for political prisoners (Hrubieszów), he manages to take pictures with a camera smuggled into his cell. He is also writing a book together with other prisoners.) (It must be remembered that during martial law the Polish People’s Republic was one big prison; in this sense, the statement “the artist was freed from prison” may be seen as ironic). In 1983-1986, Libera’s work followed parallel tracks. Above all else, the artist “burrowed himself” at home where he created several video pieces.(The artist also produces several photographs, photo-collages, and paintings.) He also participated in the activities of the Pitch-in Culture (Kultura Zrzuty) in Lódz, while forming, together with Jerzy Truszkowski, his own artistic commune (alternative to The Attic).

In his video works, such as “Intimate Rites,” “How to Train Girls,” “Mystical Perseverance,” and “Playing with Mother,” Libera worked through some ideas related to his stay in prison and his experience of the first years of martial law. These works reflect the artist’s peculiar withdrawal from life; and are an attempt to transform and bring order to the “chaos,” that resulted from his overly dramatic “relations with the world”. In Libera’s experience, moving from the most hostile place (prison) to the most comfortable place (the family home) became a way of “domesticating” and rebuilding his shaken relations with the world; it became a pretext for telling about the specific subject-object struggle of the self with the “reality of influence” as well as about “mutual relations” between the self and its surrounding.

These video works are a manifestation of Libera’s specifically “romantic” attitude—they fully explain his attitude toward metaphysics, which, despite its unquestionable originality, remains a part of a broader trend of romantic tropes and attitudes reactivated in Polish art of the 80s. Libera did not treat metaphysics as something located outside of the world, as something transcendental (as was the case in religious and para-religious art) but as a quality of the self’s “normal” existential experience, strongly present and defining its character.(In the artist’s understanding, the individual spirituality of the self is the only chance to radically undermine all rational power structures (the state, the opposition, the church) and art systems (art of the 70s, but also Lódz Kaliska).) In this approach, metaphysics (“transcendence brought into the world of immanence”) develops within the framework of alternating gifts and blows by the self and the world. In this respect, Libera’s art appears to be “suspended” between two important Polish art trends of the 80s: the romantic and spiritual para-religious art, and the Pitch-in Culture that focused on privacy, absurdity and embarrassment (a peculiar celebration of the “self’s imperfection”). 1980s’ art was, after all, a reaction against the rationalized art of the 70s, which coincided with the equally rational and overly artificial rhetoric of the socialist system (another modernist dream about the un-charmed, finally modernized and mature world).

The establishment of Solidarity, the election of the Polish Pope, and the introduction of martial law (treated as an expression of the climactic rationalism of the communist state) led the society and the artistic community to value spiritual attitudes which acquired a political dimension, becoming synonymous with protests against the system.

In art, we can observe a return to traditional media, primarily to paintings in which metaphysical connotations (transcendence, autonomy) were desirable. Moreover, paintings (colorful, strange, surreal, the harder to rationalize the better) were being exhibited in the Church (the para-religious art). This led to a convergence among the metaphysics of art and the metaphysics of religion, leading to a romance between the two transcendences.(Artists joined the revolution which was happening in front of their eyes. These are the tendencies that define the mainstream of the 80s’ art.)

In response to the above changes, Libera undertakes a “heretical” attempt to take the “appropriated” spirituality institutionalized by the Church and art and return it to the individual and existential experience of the self. His art manages to achieve the successful, but also paradoxical, fusion of the “spiritual” qualities typical of para-religious art with the qualities of “normal” human existence (celebrated in the Pitch-in Culture).

“Mystical Perseverance” and “Intimate Rites” were created after the artist took care of his over 90-year old grandmother Regina G., who was so old and sick that she could neither live independently nor communicate with the world. With devotion, and for more than two years, the artist fed her, washed her, changed her diapers, put her to bed etc.(It is worth adding here that the artist’s father died when Libera was three years old (1962). The artist was raised in a household run by his mother and his grandmother. His mother never married again.) “Intimate Rites” examines the ultimate failure of the self and the reification that awaits each one of us (aging and death). Simultaneously, however, it is also a story of the ultimate victory of the self, expressed through the artist’s caring gestures toward his sick grandmother, in the selfless gift of love.(Whenever I watch Libera’s film, I always ask myself whether I would be capable of this kind of sacrifice for such a long time. This is the dilemma evoked by this film. I think that all those who believe that the relationship between Libera and his grandmother should be regulated by the Helsinki Foundation should answer this question first.) The film simultaneously addresses the self’s greatest failure and greatest triumph. “Intimate Rites” reflects Libera’s specific transitional position in the 1980s art world. (the position of Kierkegaard’s Either/Or). On one hand, it is possible to imagine the film being shown in some Church gallery as a work about love, sacrifice, and devotion. However, in contrast to much of para-religious art, Libera did not locate these (Christian) values in the abstract, symbolic sphere (one unconnected to any effort or necessity to live these values). Rather, he documented their authentic implementation.(In this aspect (close to the Sublime), it could be interesting to interpret “Intimate Rites” through concepts of Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt, two critical philosophers (atheists) of anti-globalist bent. They look at “the language of the Gospel,” and mostly at such notions as love, from the perspective of their specific usefulness in the struggle against the language of capitalist exchange “something for something,” instrumentality of human relations, alienation and reification.) On the other hand, the film was a perfect fit with Marek Janiak’s concept of embarrassing art, one of the more interesting artistic propositions of the Pitch-in Culture. Seen within this framework, “Intimate Rites” shows Libera as an embarrassingly spiritual being, selflessly nursing a piece of the world that is close to him (his grandmother). In the context of embarrassing art, the film shows that such values as love, devotion, and selfless giving, which elude rational thinking (and at the same time radically transcend our habitual relations with other people, which are based on the exchange of something for something), may also make us feel embarrassed, showing our weakness.(The feeling of embarrassment could have been evoked (and still is) by the theme of spirituality when undertaken in the sphere of the rationalized neo-avant-garde art.)

A similar “metaphysical-embarrassing” structure is also visible in the film “Mystical Perseverance”, which shows Regina G. monotonously and unconsciously performing a simple activity—turning a chamber pot around more than fifty minutes. When still relatively independent, Libera’s grandmother used to say her rosary. Later, when her condition deteriorated and she was in danger of accidentally strangling herself with it, the rosary was taken away from her. Then, Regina G. started looking for some substitute, some object that could double as a rosary and become the vehicle for her prayer. Her chamber pot became this vehicle. Libera wrote about it in the following way: “The described work is a mystical-magical action, independent from any known form of religion, magic and art. It neither creates nor contests any system. It occurs every day, regardless of the current situation in politics, society, culture, social life, art, and finances, both official and unofficial. It always happens in the same place, and it is always experienced by one person, Regina G., blind, decrepit, and unable to leave her bed. My presence in the process of recording her experiences was random and not taken into account by the experiencing subject. The described work is immanently connected to Regina G’s existence, because, apart from physiology, it is the only activity she performs independently. It is the only form of her contact with external reality”.(Zbigniew Libera, “Mystical Perseverance,” 1984.)

In the film, we can’t practically differentiate between Regina G. and the reality of objects; the only evidence of her individuality is the gesture of “prayer” she performs. We can see her bestow meaning on the fallen piece of matter, treating it as a religious fetish. We can see her most basic attempt to “cast a spell” on the physical reality. It is an individual attempt by the self to make the world sacred —to selflessly bestow gifts upon the world.(In this work, Libera was referring to Heidegger’s metaphysical ideas, to the possibility of discovering the authentic truth as un-secretiveness (aletheia), which is hidden behind the history of the western Platonistic thought. Nonetheless, Libera’s work is based on a paradox: after all, we will never find out whether Regina G’s actions were such metaphysical attempts (as described above), or whether they were only empty conditioned reflexes.)

“How to Train Girls” was created as a result of Libera’s re-working of some video material he found in his home video collection. It presents a four-year-old girl who is being instructed on some aesthetic rites of self-creation by an elderly woman. The peculiar slowing down of the image carries this fragment of human experience beyond the moment when it was registered. Another kind of time is being introduced, a time of “re-working” the effects of a given influence (the aunt’s teaching) in the depths of the psyche, followed by a time of dissecting it (unconscious, of course, in the child’s case) in order to determine what should be accepted and what should be rejected in co-creating the self. The film presents the sculpting of character, created not in the present moment but in a particular delayed time— the “phase of active imagination.” “How to Train Girls” is, for the most part, perceived as a story about socialization and about the training used to teach definite roles. The artist intended the piece to speak about those conditions necessary for our survival—about the fact that we are doomed to aestheticize our personality, to self-create, and to transform the world influences into qualities that feed our identity. We do this continually throughout our lives, both consciously and unconsciously. It is a film about the girl’s appropriation of influenced gestures as part of a conditioned, ruthless, and necessary mutuality.(Agata Bielik Robson writes: “Psyche is slowly starting mutual relations with the world, testing its creative powers on the Principle of Reality. Therefore, it is also responding to what is missing and what reveals itself in the other, but this response is less defined than in the case of Lacan’s decision to participate in some symbolic order. Although the reality is longing for fulfillment from psyche, this fulfillment depends, to a large extent, on the creative inventiveness of the single self. The potential space – a safe play zone, where psyche is experimenting with elements of the reality, changing “transitory objects” and bestowing upon them new orders and meanings, like in a kaleidoscope – constitutes a sphere, in which the pleasure principle peacefully meets the domesticated Principle of Reality, and creative fantasies freely coexist with experiencing the world, without entering into conflict. The painful truth about the reality as a punishing hand and a disappointment, above all else, has no access here yet.” Agata Bielik Robson, The Spirit of Space, Kraków 2004, p. 479.)

All of these films examine the various systems of exchange that define any relationship, transitional and fraught with anxiety, between the self and the world. One pole of this relationship is absolute reification of the self by the reality of influence, and the other pole is its transformation into a “poetic exchange of gifts.” Libera’s films are about the self suspended between these poles. As a result, the permanently “transit” self described in these works appears as something intermediate between the Kartesian-Kantian separation of the consciousness and the world(This separation is a dramatic expression of defense “from influence” and an attempt at a utopian escape into transcendence, into complete autonomy, characteristic for the modernist poetics.) and the “death of the self,” occurring in the philosophy of deconstruction, where individuality is completely diluted in the “stream of influences”.(This lack of individuality may also be called (in reference to the romantic poetics) a kind of spiritual “return to the mythical unity with the world, to the primeval paradisial reconciliation.”) Here the self finds itself in the position of “Neither/Nor,” as defined by Kierkegaard, Libera’s favorite philosopher at that time, other than Heidegger.

The problems undertaken in “Mystical Perseverance” and in “Intimate Rites” are continued (and also summed up) in Libera’s works from the beginning of the 90s. In “Kapielowicz” (The Bather), 1991, and in “A Minute of Silence,” 1992, Libera metaphorically presents the self as an interface between the body (presented in an iconoclastic way, as “a negative”) and the world, and also as a transit (a permanently shapeless and unfinished process) between these two realms. Agata Bielik Robson writes: “At a certain point in the psyche’s development … the idea of the limiting membrane appears, from which, in turn, the idea of the inside and outside are derived.” Depth, then, turns out to be a derivative of the experience emerging at the very surface of psyche; this “spirit of space,” embodied in the limiting membrane is defined as the most important moment of the entire psychogenesis”.(Agata Bielik Robson, op. cit, p. 479.) I think that we may treat Libera’s works mentioned above,(As well as his work Christus Ist Mein Leben, which was created at approximately the same time.) these “limiting membranes,” as visualizations (tormenting the artist throughout the 80s) of the transit experience, of stopping mid-way, and of life as paradox. In these works, the artist was trying to raise his “temporary” condition to the level of a serious spiritual experience. He was summing up the 80s, questioning the phenomenon of “transfiguration,” spiritual evolution, the contemporary formula for spirituality, and longing for the “missing sainthood.” This quest reaches its climax and fulfillment in the artist’s several-month stay in Africa, in 1989-1990.

The problems undertaken in “Mystical Perseverance” and in “Intimate Rites” are continued (and also summed up) in Libera’s works from the beginning of the 90s. In “Kapielowicz” (The Bather), 1991, and in “A Minute of Silence,” 1992, Libera metaphorically presents the self as an interface between the body (presented in an iconoclastic way, as “a negative”) and the world, and also as a transit (a permanently shapeless and unfinished process) between these two realms. Agata Bielik Robson writes: “At a certain point in the psyche’s development … the idea of the limiting membrane appears, from which, in turn, the idea of the inside and outside are derived.” Depth, then, turns out to be a derivative of the experience emerging at the very surface of psyche; this “spirit of space,” embodied in the limiting membrane is defined as the most important moment of the entire psychogenesis”.(Agata Bielik Robson, op. cit, p. 479.) I think that we may treat Libera’s works mentioned above,(As well as his work Christus Ist Mein Leben, which was created at approximately the same time.) these “limiting membranes,” as visualizations (tormenting the artist throughout the 80s) of the transit experience, of stopping mid-way, and of life as paradox. In these works, the artist was trying to raise his “temporary” condition to the level of a serious spiritual experience. He was summing up the 80s, questioning the phenomenon of “transfiguration,” spiritual evolution, the contemporary formula for spirituality, and longing for the “missing sainthood.” This quest reaches its climax and fulfillment in the artist’s several-month stay in Africa, in 1989-1990.

The community around the Pitch-in Culture, as its name indicates, was based on the culture of sharing. Artistic gestures, small interventions, jokes, and absurd behaviors created in the context of The Attic in Lódz, were not, for the most part, focused on building some autonomous artistic value, but rather on creating dynamic communication within the community and establishing bonds. In this context, the Pitch-in Culture may be perceived as a community based on exchanging symbolic gifts (communiqués). Thus, the point is not about the artistic value of such communiqués (they’re often “empty” when it comes to meaning), but about their role in creating bonds (the communiqués/gifts have to be reciprocated, after all). The Pitch-in Culture was a kind of “survival strategy.”

The artists had to work out their own independent community offering mutual support and communication systems. This community wanted to function outside of both official state-run art-exhibit institutions and anti-official Church galleries. In the area of art, the Pitch-in Culture was a reflection of the punk counterculture that flourished in Poland at that time. We might actually call the Pitch-in Culture a punk scene of the Polish art.(With all of its anarchism, opening up toward the outsiders’ creativity and affirmation of strange heretofore marginalized art forms; with its fondness of provocation, obscenity, embarrassment and risky and drastic behaviors; with its flaunting its own shapelessness, immaturity, lack of sophistication and taste; with its affirmation of enthusiasm; its energy and intensity of experience here and now; and with its singular nihilism.) As far as its artistic genealogy is concerned, the Pitch-in was dominated by the neo-dadaist artistic poetics (based on absurdity and provocation), its negative point of reference located in the rational, neo-constructivist art of the 70s. The Pitch-in Culture radically rejected any links to spirituality.

Zbigniew Libera participated in the initiatives undertaken by the Pitch-in Culture and The Attic Gallery almost since their creation.(His first individual show in 1982 was the first show ever presented there. Libera showed photographs from old German films of the fascist times. Children’s drawings were located on the back of these photographs. Libera co-edited a few issues of the assemblage magazine Tango, produced and distributed his own publications, and documented many open-air workshops, as well as many various artistic ventures undertaken by the community, with his own video equipment (for example, he was behind the camera in documenting Marek Janiak’s Liberating Actions). However, his full integration into the Culture of Pitch-in was made impossible by the fact that one of its members, blackmailed by the police, informed on Libera and caused his imprisonment.) Finally, however, Libera’s relationship with this community weakened in 1985, when, together with Jerzy Truszkowski, the artist decided to create a separate artistic community.

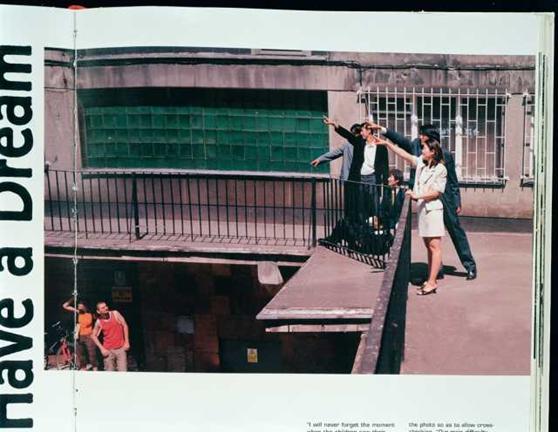

In his co-creation and participation in these artistic communities Libera was again attempting to “transform” the hostile world into a home. It was an attempt to rebuild a sense of power and security in his relations with reality—a chance to enter into a mutual relationship with reality. Libera and Truszkowski shared an interest in the spiritual dimension of art and existence, as well as in exploring the individual’s self-creation potential.(However, Libera represented a radically different type of personal self-creation and aestheticization of his relationship with the world from those represented by Truszkowski. Pushing “spiritual life from the sphere of necessity to the sphere of aesthetic possibilities” to its (dangerous) extreme, Truszkowski reactivated the romantic myth of an artist challenging God, striving for power, and fascinated with leadership and the leader. Libera distanced himself from Truszkowski’s concept of metaphysics i.e., from his narcissistic fantasy about the absolute autonomy of the self, completely dominating (and outshining) over the reality. The artist distanced himself from this position because he knew (from personal experience) the reality’s “power of influence.” For the same reasons, he also remained distanced, but also appreciative, toward radical performances of Marek Janiak from Lódz Kaliska and toward Zbyszek Trzeciakowski’s works. Both involved life-threatening and radical existential experiences. For example, while at a tenth floor of a Lódz high-rise, Janiak would bend over a balcony railing, trying to gain balance. This kind of a balancing act involved a 50% chance for falling down and death.) Together with other artists with similarly “metaphysical” interests, including Barbara Konopka and Jacek Rydycki, they created a provocative and iconoclastic presence that was embarrassing not only to so-called society but also to their former artist-friends. Their main goal was a creative, intense and “colorful life,”(Characterized by liberated sexual behavior.) which was, itself, a way to undermine the ugliness and apathy of existence in Poland during martial law. Among other things, the artists painted together, started a punk band, Sternenchoh, and organized actions and happenings together with patients from the mental hospital where Libera worked at the end of the 80s.

Zbigniew Libera’s art in 1989-2005 was a consistent continuation of his artistic and existential quest during the 1980s. Also in this period, Libera created cycles of work that reflected on the various contexts for creating and shaping his own identity. Every cycle was, after all, a kind of “transformation of unwanted blows of the real,” an attempt “to change the hostile world into a home.” The “Corrective Devices,” for example, was created as a response to common self-creation processes, enforced by the transformation of the political system in which the artist naturally participated. “Masters” came as a reaction to the censorship of his work at the Venice Biennale after he realized that his artistic identity was, to a large extent, created outside of himself by the world of art institutions. “Positives” was created as a reaction to the mass media’s attack on the artist and the art he represented; moreover, in this cycle, the artist summed up his more than twenty years of thinking about the relationship between the self and trauma. In each cycle, Libera was trying to surpass his individual experience, to analyze and design a space of common values, shared by larger human communities.

Libera’s cycle of work known as “Corrective Devices” was made a response to the early years of growing capitalism in Poland after 1989, which become a time of “romantic” challenge, an environment of shared creativity and creation. The new reality of accelerated modernization mandated a new sense of self and new rules for public life. The fall of communism, and the final “death” of history that accompanied it, also propelled a complete change in perspective concerning the self. The necessity to define oneself in relation to history, community, humanity and to the mass ideologies dominant in the 80’s, in the 90’s was superseded by the “politics of identity,” with the self responsible for its own identity, development, and (singular) life project. In the 90s, the romantic “self-creation,” which in the 80’s was carried out by desperate individuals (including Libera), became a mass phenomenon and mass obligation. In the time of post-socialist post-modernism, the market becomes a new part of identity construction, vital and growing in strength. It turns out to be a perfect ecosystem for the army of eternally undefined and permanently immature selves in transit, the army of radically different selves, still involved in the process of differentiation, whose only common denominator was vagueness.

After returning from Africa, Libera began to build his artistic identity while joining in the common process of aestheticizing the self which now characterized the system’s political transformation. Libera was aware that his “survival” depended on creating himself in the context of the institutional art world, which at that time in Poland was still underdeveloped, full of complexes, and learning the very basics of professional work. The starting point for this construction process was Libera’s adventurous and subversive artistic biography of the 80’s, exceptional in the Polish landscape but similar to biographies of such American artists as Nan Goldin, Mike Kelley, and Larry Clark (whose work and life addressed issues of excluded people: the sick of various kinds as well as prisoners, and ways to create specific “communities of prisoners” and “communities of the sick”). It is important to note that Libera did not graduate from an arts college, so his decision to become professionally involved in art —to become an artist—was related to the ongoing (and actually obsessive) reflection process concerning What does it mean to be an artist? What is art? What for? What is it I want to say? And so on. It was also related to a permanent tendency to intellectualize and the need to work out (for himself) some deep justification for his every artistic gesture. Key to meeting this need was the mutual education process he was involved in, together with Zofia Kulik and Przemyslaw Kwiek, while Libera lived with them for over two years at the end of the 80’s.

Moreover, the artist’s self-aesthetizing process (building himself as an artist) was supported by the gradually growing acclaim of his work from the 80’s, which began to be seen as a precursor to the art of the 90’s. Libera is actually applauded as the “father” of the critical art of the 90’s. And this is all due to a new reading of his early video works within the context of issues related to the body (old, sick, dying, excluded from the dominant visual norm), and gender (“training” the self to perform defined social roles). All of these components were the foundation on which Libera began creating his own, individual strategy for life and art, creating himself as an artist.

At his most important 90’s art show, “Corrective Devices,” at the Modern Art Center in Zamek Ujazdowski, Libera introduced the problem of aestheticization—the shaping of the self—into visual contemplation and reflection. This exhibition was an attempt to reframe his experiences from the early period of political transformation related to building the new man and the new society (in other words, to the aesthetic re-socialization of the former society of inmates) within the context of the newly-born Polish culture of consumerism and corporations.

Libera’s exhibit “Corrective Devices” was the first artistic expression in Poland that radically and clearly articulated a protest against consumerism. The artist’s mutated toys and other devices “afflicted with a virus” reflected, in a very specific way, the monstrous, mafia-like atmosphere of Polish early capitalism. They illustrated a characteristic fascination with consumption and portrayed the libidinous excesses resulting from a sudden, unlimited access to consumer goods that had been inaccessible before. They showed a “beautifully dressed” regress into an almost tribal stage, returning to nature, to animal instincts — a regression that was stronger than culture and any kind of rationality. This irrational element, so prominent in 80’s art (also in Libera’s art), was identified as belonging to the culture of consumption. Moreover, after 1989, the spirituality awaken in the 80’s became a doubly appropriated “language.” On one hand, there was still a monopoly of the Catholic Church when it came to expressions of these issues. On the other hand, metaphysics was also reborn in the area of quasi-metaphysical fantasies produced by culture industries, continuously growing in power in the new, capitalist Poland. It was reborn in the “worlds,” “lifestyles” and “realities” produced by commercialized pop-culture, mirroring the Weber and Benjamin’s notion of “casting a spell over the world again” by “reactivated mythology,” or in other words, by appropriated spirituality, producing a diminished, standardized spiritual life.

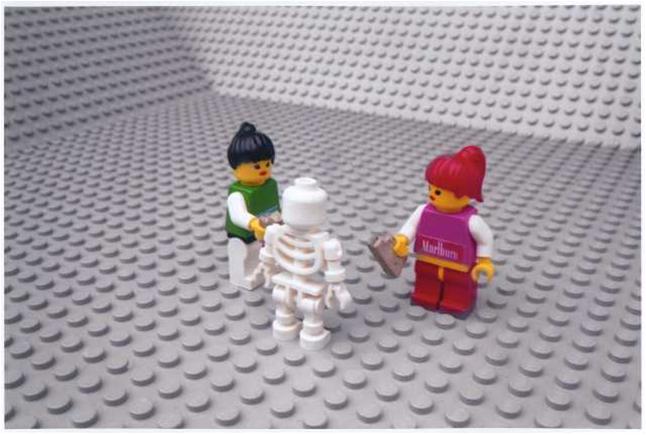

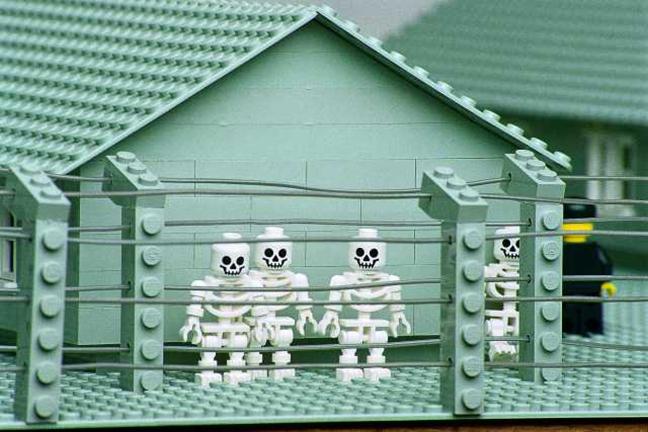

The problem of restitution by the new quasi-totalitarian system within the framework of consumerist culture is also undertaken in “Lego,” the key work in the “Corrective Devices” cycle. To a large extent, the work is an extension of Libera’s 80’s works relating to the artist’s analysis of his imprisonment (in the monstrous conditions of the People’s Republic). Through the theme of imprisonment, in “Lego – The Concentration Camp,” Libera strongly focuses on analyzing the relationship between the executioner (ruling) and the victim (passive). Proposing this “Holocaust Game”, Libera creates a sphere of identification either with the executioner or with the victim. “Identification dominates over representation (…) drastically and rather shockingly, the goal of identification moves from the victim to the torturer.” After all, like all the “Corrective Devices,” “Lego” is also to be used for performance, for identification, for playing a part, and for the imaginary act of “becoming someone” (in the process of building the self). Libera seems to claim that the Holocaust is not located “above history” (in a different – actually sacred – order of reality) but it is definitely a part of history that may even be repeated (it may be performed again). This opportunity for repetition results from the hyperbolized traits we all have—on the one hand, the will to rule, and on the other hand, an inclination for conformity. This dialectic (the reifying influence of reality and an attempt to control it) was particularly important for Libera in the 80’s, and now the artist updates it, asking about the boundaries of our current will to govern and rule.

In the context of “Lego” (and other “Corrective Devices”), the artist’s works are most visibly ambivalent (in a way characteristic for pop-art). On one hand, they are critical toward the process of “shaping, forming the body and the mind,” but on the other hand, they are an expression of fascination with these processes, an expression of conviction regarding their unavoidability. Trying to dissect and reveal the processes conditioning self-creation, Libera is trying to equip individuals with instruments for a more conscious shaping of the self (one’s identity and spirit).

The apogee of the success of the “Corrective Devices” exhibit was Libera’s selection as a participant in the Polish Pavilion in the 1997 Venice Biennale. The primary aim of Jan S. Wojciechowski, the show’s curator, was to bring together criticisms of consumer society (Libera) newly born in Poland at that time, and attempts to settle scores with communism (Kulik), a trend visible for a while in the area of art. By juxtaposing the artistic critiques of these two systems for imprisoning the body and the mind, Wojciechowski intended to construct a story of Polish political transformation as seen through the lens of art. Moreover, Wojciechowski wanted to complement Kulik and Libera’s show by presenting Oskar Hansen’s “Open Form,” a kind of “father figure” for both artists. In this context, Hansen’s “Open Form” became a methodology (shared by both Kulik and Libera) for “illuminating” influence relationships (mechanisms) between the self and the world, and on strengthening the self’s right to self-determination, to construction of itsown identity. Unfortunately, despite this great curator’s idea, Wojciechowski objected to showing “Lego – The Concentration Camp.” He believed that showing the work in the Polish national pavilion could lead to a serious international scandal (he primarily meant Polish-Jewish relations). The curator’s paradoxical decision (since at the onset he was “building” his idea for the show on Libera’s “Corrective Devices”) led to Libera’s decision to completely withdraw from the Biennale. The artist felt hurt by the immature discourse among institutions and bureaucrats in the field of art in Poland, unable to defend the art or the artist, his work, his strategy, his specific artistic language, and fearful of any attempt at being pushed into an open discussion. These immature institutions (including art criticism) were shown in contrast to the mature and resolute decision of the artist. It was an important gesture for Libera, who was at that time involved in a continuous process (beginning on his return from Africa) of self-construction and of strengthening his artistic identity, where the artist, as an entity, was involved in a conditional relationship (symbiosis/struggle) with other artistic institutions. More and more clearly, Libera began to realize that his position as an artist—his artistic identity—was, to a large extent, conditioned by the world of art institutions (independent of him). The cycle “Masters” was created as a reaction to this situation. The double failure of the 70’s neo-avant-garde artists (with whom Libera identifies when it comes to a level of repression) becomes his way of telling about his own conflict with the art institutions and the failure of the critical art of the 90’s.

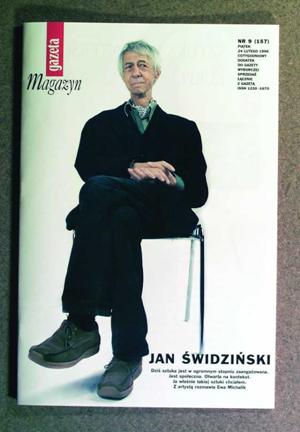

In “Masters,” Libera reflects on his entanglement in the art world and on the conditional character of his artistic production, remaining in a continually dependent relationship with the context of its creation, a context that determines the specific value of Libera as an artist, and of his art. And this value results from the mutual influences of various forces: marketing, the prestige of a gallery showing the artist, the gallery that represents him, fashion, promotion, financial resources and, finally, art criticism. “Masters” is Libera’s reflection on this specific context, on what, according to the artist, determines the value of an artist and an artistic strategy in Poland. Drawing conclusions from the past decade’s conflicts “between art and society,” Libera seems to claim that in Poland, the artist’s value is designated by popular press critics, that a short article published in Gazeta Wyborcza (Electoral Gazette) means more than the biggest catalog published by the Zacheta Gallery. “Masters” allows Libera to pose a sequence of questions regarding his identity as a creator and his artistic roots; they are attempts to “domesticate” “his home” – the art world.

It’s worth noting that in the cycle “Masters,” Libera carries out his “pedagogical discourse” using a set of visual-textual props similar to “instruction charts and technical and scientific visualizations.” This work, located at both the intersection of art history and art and the artistic and the educational processes, belongs to that specific artistic tradition of Atlases/Photographic Archives described by Benjamin Buchloh in “Gerard Richter’s Anomic Archive.” The common trait of the artifacts described by Buchloh was the fact that — unlike photomontage, for example, which also uses fragments of ready-made photographs and texts, and confirmed, in a way, the heterogeneous and fragmentary nature of the reality— this concept allowed artists to classify, to order, and to archive various aspects of reality. It helped to find order in a world characterized by chaos and over-production of images and information. As a technique, it supported the process of personality integration, and that’s why it seemed so attractive to Libera.

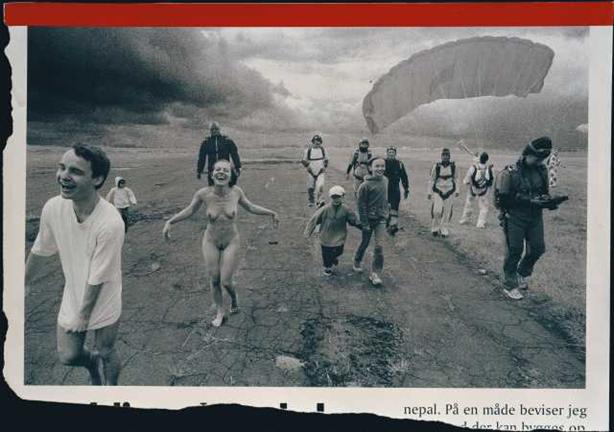

Zbigniew Libera’s “Positives” are a cycle of staged photographs presenting positive versions of well-known “traumatic photographs,” such as, for example, those of Vietnamese children burnt with napalm, concentration camps’ prisoners, Che Guevara’s corpse, soldiers’ corpses half-covered by snow etc. In this cycle, the artist sums up a reflection on the nature of traumatic experiences that permeates all of his artistic work and on ways the self copes with these experiences. While in the 80’s and 90’s Libera’s works showed a directly psychotherapeutic attempt by the self to work through sudden trauma, in “Positives,” based on “the logic of repetition,” we can see a lab analysis of the relationship between trauma (the real) and its representations (attempts at working through trauma by the self’s psyche). The artist seems to claim that the effects of trauma can’t be fully illustrated and represented, they can only appear in our imagination as “post-views” (similar to the process that occurs when viewers of his works remember the originals of his staged photographs – which becomes a metaphor for the relationship between symbolic representations of trauma and its indescribable, real traumatic model). “If a traumatizing encounter with the real is not recorded in any clear sign form, but only comes into presence later, in a Repetition, then there is no reason to insist on the primary character of the trauma: repetition is something primary, because it brings about this encounter for the psyche (…) What is real cannot be presented directly, because the essence of trauma is that the psyche is not ready to represent it and capture it in words. Therefore, in the life of the psyche, the real can only appear in the form of unclear repetitions.”

In creating the “Positives,” Libera seems to claim that this is the way the original photographs should look if they are to accurately depict the nature of the relationship between trauma (the real and the indescribable) and attempts at its presentation (working through it by the self’s psyche). Paradoxically, in this context, Libera’s “Positives” are more authentic than their models. After all, they don’t cheat by suggesting they successfully capture the picture of the real trauma and know its essence. In its perverse iconoclasm, Libera’s work allows us to come much closer to “the dark root of trauma” than do the initial photographs on which the “Positives” are based on. “Positives” show the self’s conditional process of anesthetizing the sinister world. This is the process of enclosing this world in representation. Its very appearance, in lieu of “the real”, is a positive fact, since it simply can’t be any other way. Thus, in the context of Libera’s work, the saying “every cloud has its silver lining” acquires its deep conditional sense.

The above text is an attempt to interpret Zbigniew Libera’s work through the lens of “the identity paradigm,” which suggests a close link between the artist’s life and work. Libera’s art is, after all, defined by a permanent reflection on identity, its creation and shaping: in the context of Poland’s repressive political system (video works of the 80’s); an emerging consumer society (“Corrective Devices”); art institutions (“Masters”), the post-transformation reality (“Positives”). For 25 years, the reality in which the artist was “immersed” was characterized by constant social and political turmoil, by chaos and uncertainty in the epistemological sphere (including the lack of universal meta-narratives that could organize human experience). This forced Libera to be permanently worried about his identity and to be working constantly on integrating his experiences. This was not easy because at every stage of his life the artist involved himself in (or was thrown into) the most extreme and traumatic situations. That is why the character of Zbigniew Libera’s life and art was defined by constant metamorphoses, continual destruction and redefinition (the type of the self he implies is close to “the ironic” – Schlegelian – model of anesthetizing life). This is also why Libera’s whole creative output may be understood as a reflection on the self when faced with the gradual destruction and fragmentation of the post-modern world. It is a reflection on one’s ability to establish self-rule as a way to integrate one’s individual narrative among the millions of choices and sudden (traumatic) events that fill this world.