Vladimir Havlík and Barbora Klímová, “Yesterday”, Parallel Gallery, Prague, June 4, 2009 – June 28, 2009 (Exhib. Review)

Vladimir Havlík and Barbora Klímová, Yesterday, Parallel Gallery. Prague, June 4, 2009 – June 28, 2009

The show at Prague’s Parallel gallery entitled “Yesterday” can be linked to a series of recent investigations by younger artists from countries of the former Eastern Bloc who take on the Communist past by way of its often decayed or discarded visual records, from photographs to videos and short films. While photography has been part of this endeavor for some time – in Russia, older artists such Boris Mikhailov and Alexei Shulgin come to mind, although their manner is more conceptual than that of the younger generation -, film and video have only recently entered the fray. The crucial work here is Anri Sala’s Interview (1998), the Albanian-born artist’s confrontation of his mother with a long forgotten video (without sound) that shows her, twenty years earlier, giving a fiery speech to the Albanian Communist youth organization. The fascination of Sala’s approach lies in the extreme flexibility with which he exercises his own position as an observer both involved and aloof – devoted and critical – at one and the same time. Lovingly at his mother’s feet at one point, in the next moment Sala coolly registers her reactions as she recognizes herself, mouth open, in the long-forgotten video. Apart from Sala, artists as diverse in their interests and critical disposition as Hito Steyerl, Anca Benera, and Marysia Lewandowska have analyzed, each in their own way, the now distant Communist past or its equally distant aftermath – the heady 1990s – by uncovering the visual archives that survived it more or less intact. Avoiding, for the most part, the false sense of nostalgia that often accompanies our traffic with old films, these artists have insisted on surrounding their found material by multiple – and shifting – narrative frames that prevent the viewers from lastingly fixing their viewpoint on what they see.

The show at Prague’s Parallel gallery entitled “Yesterday” can be linked to a series of recent investigations by younger artists from countries of the former Eastern Bloc who take on the Communist past by way of its often decayed or discarded visual records, from photographs to videos and short films. While photography has been part of this endeavor for some time – in Russia, older artists such Boris Mikhailov and Alexei Shulgin come to mind, although their manner is more conceptual than that of the younger generation -, film and video have only recently entered the fray. The crucial work here is Anri Sala’s Interview (1998), the Albanian-born artist’s confrontation of his mother with a long forgotten video (without sound) that shows her, twenty years earlier, giving a fiery speech to the Albanian Communist youth organization. The fascination of Sala’s approach lies in the extreme flexibility with which he exercises his own position as an observer both involved and aloof – devoted and critical – at one and the same time. Lovingly at his mother’s feet at one point, in the next moment Sala coolly registers her reactions as she recognizes herself, mouth open, in the long-forgotten video. Apart from Sala, artists as diverse in their interests and critical disposition as Hito Steyerl, Anca Benera, and Marysia Lewandowska have analyzed, each in their own way, the now distant Communist past or its equally distant aftermath – the heady 1990s – by uncovering the visual archives that survived it more or less intact. Avoiding, for the most part, the false sense of nostalgia that often accompanies our traffic with old films, these artists have insisted on surrounding their found material by multiple – and shifting – narrative frames that prevent the viewers from lastingly fixing their viewpoint on what they see.

Such frames were also present in Barbora Klímová’s and Vladimir Havlík’s installation at Parallel gallery. The most important frame, in a sense, was the very collaboration between Klímová – a Brno based artist and curator -, and Havlík. Klímová, who had already worked with the artist for her contribution to last year’s Manifesta (where her focus was on Czech performance art during the 1980s and its investigation of public space) went through Havlík’s archive, selecting three open-ended videos that the artist, reluctantly, allowed her to use. In this way, the resulting show at Parallel gallery was very much the product of a political ritual that is familiar to anyone in the countries of what used to go by the name of Eastern Europe – it resulted from a “struggle over the archive.” Klímová went on to mount Havlík’s videos on three TV monitors in two gallery rooms where they were shown in loops.

Such frames were also present in Barbora Klímová’s and Vladimir Havlík’s installation at Parallel gallery. The most important frame, in a sense, was the very collaboration between Klímová – a Brno based artist and curator -, and Havlík. Klímová, who had already worked with the artist for her contribution to last year’s Manifesta (where her focus was on Czech performance art during the 1980s and its investigation of public space) went through Havlík’s archive, selecting three open-ended videos that the artist, reluctantly, allowed her to use. In this way, the resulting show at Parallel gallery was very much the product of a political ritual that is familiar to anyone in the countries of what used to go by the name of Eastern Europe – it resulted from a “struggle over the archive.” Klímová went on to mount Havlík’s videos on three TV monitors in two gallery rooms where they were shown in loops.

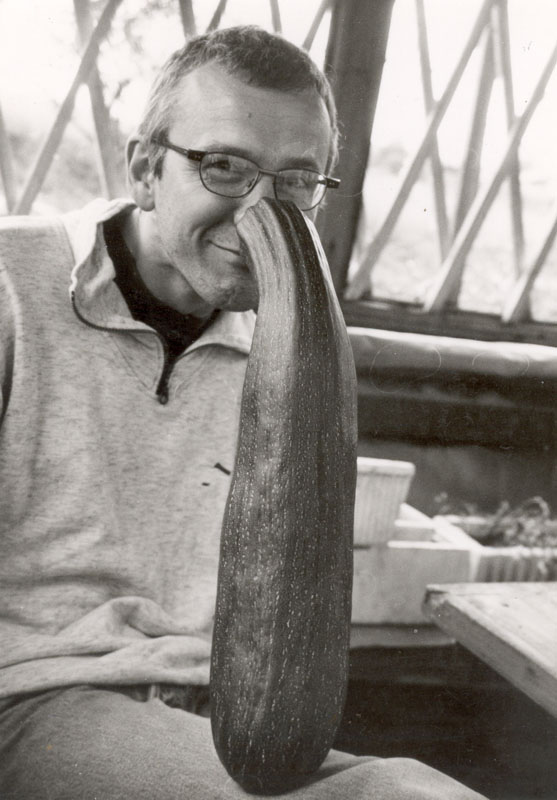

Havlík had shot all three videos in the early 1980s in his hometown of Olomouce and had not paid attention to them since then. The videos themselves are inconspicuous yet strangely organized at the same time. We observe young Havlík engaged in a variety of activities – cutting his own hair (he had been ordered to do so by the authorities but then decided to take matters into his own hand); outside with his girlfriend, or in his room in the student commune in which he lived at the time with a hydra-like monster made from pillows. All three films not only document the youthful underground in a provincial Czech town during a particularly oppressive period, they also have a strange patina about them – it is as if Havlík and his friends were protagonists in their own reenactment of 1970s Hippie culture. For the viewer, this fact resulted in a double effect of belatedness – for we, too, are late to realize that life in the 1980s was not as monolithic, gray and uniform as we have come to believe. Another twist to Havlík’s shorts was the fact that they were experiments in (self-) observation, born from the – perhaps naive – belief that the once-liberating potential of media such as film could be recuperated. This, their youthful avant-gardist optimism, was no doubt the most touching element in the videos on show at the Parallel gallery. And it may have been the reason why these fragments appeared so intensely private and public at one and the same time. As self-reflexive diaries of 1980s youth culture, Havlík’s films demonstrate that nothing is quite so subversive – and, I might add, poetic – as archives. Klímová wisely opted not to give the films any identifying titles or captions, for fear that these might make them more literal and one-dimensional than was necessary. Instead she asked Havlík to add short texts to stills from these and other films in an accompanying brochure. In this way she forced the filmmaker to confront his own work in a way that precluded facile identification. Communism, indeed, seems like a distant memory.