The Body in the Sphere of Literacy: Bakhtin, Artaud and Post-Soviet Performance Art

Bakhtin’s struggle against the abstraction of literature creates a strong structural analogy to Antonin Artaud’s conception of theater, which has also been inspired by the vision of transcending textual-based theater; Artaud’s “theater of cruelty” aims to lead the individual back to theater’s archaic roots of self-constitution.

However, Bakhtin and Artaud approach the issue of textual representation from opposite sides; since Bakhtin favors the spoken word, his critique is directed against the abstract literacy of books, thus making a reference to the theatrical. The aim of Artaud’s critique, on the other hand, is aimed at the Western tradition of theater itself, as it doubts its textual and literal foundation. Yet both sides show a particular interest in the dialectics of the body as a basic medium of aesthetic and ethic innovation. While Bakhtin develops the concept of the “grotesque” body, Artaud requires the artists “to traumatize their bodies methodologically.”

A discussion of Bakhtin’s and Artaud’s re-conception of theatrical representation requires both a theoretical and a practical perspective. A theoretical perspective allows us to study the basic mechanics of visuality and verbalization, as well as the language and the body in theatrical representation. A practical perspective, such as that of Bakhtin and Artaud, may help to better understand forms of performing arts that are highly body-orientated, such as those of late Soviet and Post-soviet arts and culture.

Throughout the modern theater movement – including Strindberg, Mejerhol’d, Brecht and, of course, Artaud – we find a general tendency to subvert, or even eliminate, constitutional elements of theater. In order to understand the modern conception of theater, it is helpful to recall some of the media-theoretical basics of ancient Greek theater.

What Friedrich Nietzsche’s late-romantic view calls “the spirit of music,” (responsible for the “birth of tragedy”), can be traced back to the alphabetization in ancient Greece. Theater was one of the phenomena resulting from the invention of the phonetic alphabet, and as such it functioned as an amplifier of the cognitive, emotional and sensory effects of alphabetization, ensuring that all members of Athenian society, regardless of whether they were literate or illiterate, would acquire and internalize these effects (Kerckhove 1981, 23). These effects can be summarized as follows:

1) Theater turns visuality into an autonomous medium. It helps to develop a focused and distanced vision able to function independently from other senses or sensations. Whereas the sort of visuality required in daily life is always integrated into the blend of other sensations, the visual perception learned in the theater is removed from this context, as it is purely one-directional (27).

2) Theater removes the senses from the contents of knowledge and the forms of memory. At first glance, this may seem paradoxical, because we are used to contrasting the sensations and emotional qualities of dramatic activity with the evident rationality of the written word. However, rational abstraction can also be found in the theater, because it is here that people first began to cultivate the typical Western habit of dividing sense into meaning and sensation. Theater seems to have been invented to enhance the separation of the mind from the senses, to teach us to divide mind and body (29).

3) In the theater, body and knowledge, or somatics and semantics, are separate from each other. This separation works on different levels. Body and knowledge are separate with respect to the production and reproduction of text. Whereas epic singers emphasize, and indeed, embody, the content of their narration in an attempt to communicate their emotional state to the listeners, writers of tragedies have to consider the content of their narration as an abstract substance that stands apart from both the main action and the tragic character. In writing tragedies, a rational interpretation always has to precede the action itself. In theater, the performance of language loses its direct physical foundation. In traditional epic narration, body and text appear as a unity, an integrated whole; there is no external text. The story is embodied and absorbed by both singer and audience. By contrast, the theatrical actor represents a character; by externalizing a character, he/she automatically assigns the status of an independent and depictable role to it. This also forces the spectator to observe the actor from a distanced and external position. In addition, the function of the ancient chorus is defined by the transformation of all spontaneous emotional and somatic reactions of the spectators into a state of self-observation. These separations of language, text and knowledge do not necessarily mean the loss of an archaic unity; still, they have to be viewed as a basic precondition for the understanding of somatics and semantics as two independent systems that each have their own dynamics.

The independent status of seeing, and the separation of semantics and somatics, of knowledge and life, have a fundamental impact on the position of the individual in the world. In a world dominated by hearing, perception is always located in the middle of reality itself. This is why oral culture makes no categorical discrimination between subject and object, between self and other. Writing and the theater provide the cognitive precondition for taking a step back and observing from a distance. It is no longer the world that flows through the human being; now, in contrast, the individual turns the world into the object of his or her theoretical and practical interests (30).

One thing that all the different manifestations of modern theater have in common is the desire to eliminate these conceptual elements, since these are fundamentally linked to the “birth of tragedy” that came out of writing.

One very interesting example is the Russian avant-garde tragedy Vladimir Majakovskij (1913). The play was not only named after its writer, but the poet himself also performed on stage. This egocentric juxtaposition of writer, character and actor can be interpreted as an attempt to reunite language and text into one body, just as epic singers did in oral culture. It is an attempt to reverse a constitutional element of the cognitive concept that underlies traditional theater. Pirandello’s play Six Characters in Search of an Author (Sei personaggi in cerca d’autore; 1921) and Brecht’s idea of an epic theater fit into the framework of trying to lead theater back to its epic roots.

There have been innumerable suggestions to tear down the boundaries between actors and spectators, making the spectators a part of the play itself – some of these made by the Russian symbolist Vjacheslav Ivanov, by the avant-garde bio-mechanic Vsevolod Mejerhol’d, and by the French surrealists (among them Antonin Artaud). All of these suggestions aim to subvert the concept of perspective perception by the self-conscious individual spectator. The same tendency can be found in the famous play Pobeda nad solncem (1913), written by Chlebnikov, Krucenych and Matjushin: Here, synaesthetic language experiments and phonetic poetry are used to transform the visual space of the theater into a space of acoustics. Malevich reinforced this by his design of sets which make a three-dimensional space appear two-dimensional.

On this foundation Bakhtin and Artaud base their ideas on theatrality and representation. Both consider theater as a place in which the written foundation of culture may be examined and criticized, and the separation between mind and body overcome.

In his essay on linguistics, The Word in the Novel (Slovo v romane) , Bakhtin repeats, to some extent, Plato’s skeptical discussion of writing, voice and oral communication, paying particular attention to the physical foundation of speaking. He points to the “sensation of verbal activity” – a “sensation that involves both the organism and the activity of creating meaning”. He speaks of a “concrete unity” of “the flesh,” of “the spirit of the word,” and of the unity “of the active soul and body” (Bakhtin 1975, 62 and 64 f.).

The corporeality of voice constitutes a sphere of communication and mutual understanding, which is why the Bakhtinian voice and corporeality are closely related to dialogue. As mentioned above, the traditional form of theater originated from writing, which functions much like a medium for the internalization of literacy. Hence it is no longer surprising that, in his discussion on dialogue, Bakhtin systematically contrasts his own interpretation of dialogue and dialogism with its traditional conception. He rejects dialogue “as a compositional form of speech” (92), as well as “pure dramatic dialogue” (176), because he realizes that the dramatic dialogue of the traditional theater can never achieve the desired resurrection of the corporal and embodied word. Bakhtin also recognizes that dramatic dialogue functions as a communicational nucleus for various forms of differentiation, such as I versus the Other, internal versus external, observing versus acting. This is the starting point for Bakhtin’s criticism of traditional dramatic dialogue, which moves towards the conception of an “immanent,” “inner,” and even “natural” dialogism. (In this context, it is interesting to note that according to Bakhtin, no research has as yet been performed on these forms of dialogism, 92). There are three areas in which Bakhtinian dialogism goes against the fundamental conditions of traditional theatrality and representation.

1) In traditional theater, every dialogical repartee denotes a different perspective and an individual point of view. For Bakhtin, by contrast, the repartee is always under the influence of the dialogue partner, “bonded inseparably with the response, the motivated repartee” (94). Bakhtinian dialogism subverts individuation.

2) In traditional theater dialogue, all participants – both actors and spectators – are permanently confronted with the differentiation between individual utterance and objective context. For Bakhtin, however, all dialogue partners are inevitably dominated by context: “The repartee is formed within the context of the entire dialogue that exists; it is formed and assigned meaning to by one’s own (the speaker’s) and the other’s (the partner’s) utterances. The repartee cannot be separated from this mixed context of utterances by Self and Other without losing its meaning and tone. It is an organic component of an undifferentiated whole” (97).

3) Most interesting is the third element of the Bakhtinian subversion of the traditional theater dialogue; Bakhtin uncovers a so-called “inner dialogism” that is located in the depth of every word, regardless of the specific dialogue situation: “Every word is directed towards an answer and cannot escape the far-reaching influence of the anticipated repartee” (93). Most significantly, Bakhtin discovers this inner dialogism in literature, that is, in the written text: “Inner dialogism penetrates the conception of an object through the word, and gains its internal expression through transforming the semantic and syntactical structure of that word. The changing dialogical orientation seems to become an event of the word itself, vitalizing and dramatizing the word in all its elements (…)” (97). This inner dialogism and the ambiguity of the word are well-known hermeneutic effects of literacy, that is, of aesthetic writing. And what Plato had anxiously perceived as the risk of misunderstanding is now interpreted in a positive way by Bakhtin. The impossibility of eliminating the ambiguity of the written word is taken as a proof that the world of oral speech is still alive, even in the isolated written word. Ambiguity makes language a corporal process. This third element clearly reveals the function of dialogue, and also the references to theater in Bakhtin’s argumentation: theatrality works to translate literature back into life. Hence, Bakhtinian theater tries to eliminate the effects of literacy in favor of an oral, spoken and corporal form of social community.

Bakhtin deals with theater more extensively and directly in Rabelais and His World. Here, he discusses various forms of theater in the late middle ages and early modern times, such as mystery plays, scholastic dramas, commedia dell’arte,, diableries, and street theater. In addition, he discusses a “comic drama,” namely the Play in the Summerhouse (Jeu de la Feuillée), which was written by Adam de la Halle, a poet from Arras, in 1262 (Bakhtin 1990, 283). Bakhtin points out that this play already includes the whole world of Rabelais “in nucleus.” In coherence with the idea that the entire text by Rabelais originates from a particular form of play in the late middle ages, Bakhtin states that there is also no author more suitable for “scene performance” than Rabelais. Indeed, Bakhtin reads Gargantua as if it were a theatrical text.

Bakhtin has a very specific kind of marketplace-theater in mind. Using Francois Villon’s Tragic Farce as an example, he repeats the main idea of the 1920s theater avant-garde, which emphasizes that such a theater of the marketplace always performs “without stage, in the middle of life itself” (291 f.). Here, “there is no separation into participants (actors) and spectators; they all play together, (…) no dividing line exists between theater performance and real life” (292). The type of theater that Bakhtin prefers and that he finds in the grotesque devilries and the commedia dell’ arte is characterized by what he calls the “marketplace-component”. This type of theater always transcends the stage and mixes with the life of the marketplace. According to the avant-garde concept of Bakhtinian theater, the spectator is no longer a distanced observer, but becomes an actor of a dramatic situation himself. This “marketplace component” proves to be an aesthetic principle of Rabelais’ text, one that Bakhtin thought worth discussing in an especially long chapter.

By eliminating the stage and locating the spectators in the middle of the theater event, the scene changes from a visual space to an acoustic one, one that is filled with voices and shouts –so-called cris de Paris, used by marketplace-actors to communicate with their environment. These cris include everything: the cries of merchants and dealers advertising their wares, curses, puns, swearing, praise, science and philosophy. Important are their pragmatics: “The speaker always declares his solidarity with the crowd on the market place. He is not separate from it, he does not teach it, he does not expose it, and he does not frighten it; he laughs together with it. His speech does not even have a touch of sinister seriousness, of fear, reverence and humility. It is the cheerful, fearless, open and uninhibited speech of the marketplace, unrestricted by taboos and conventions.” (299)

In this acoustic space, language loses its distinctive denotations. The marketplace is dominated by semantic inversions and travesties. Everything becomes an object for puns, for reversals of semantic opposites, for disguises, jokes, deceptions, illusions (255). Everything here has to do with language as a pure performing act and the comic and grotesque activities of producing words. As Bakhtin shows in an example taken from commedia dell’arte: “The articulation of a complicated word is staged like a birth” (391), and: “The borders between body and world are removed” (344 and 350). On this marketplace, language is led back to its bodily foundation and appears as an event and staging of the body. In this purely acoustic space of the marketplace the community itself creates a speech-community, one whose ethos bears no visual signs or symbols, but is exclusively acoustically orientated.

In this respect one motif is most remarkable: the motif of book-trading, which is exposed again and again by Bakhtin, far from any historical authenticity and in a very specific manner. Bakhtin does not interpret booktrading as an economic procedure of trading properties of knowledge, but as the permeation of book-knowledge into life. He repeatedly describes how, on the marketplace, the abstract and exclusive medical, philosophical or theological book-knowledge can be at last proved and criticized on a corporal level. What’s more, it is not the individual body that appears as the final basement of abstract book-knowledge, but the marketplace turns into a space where all those bodies separated by degrees of literacy merge once again into the whole of a social body; here a total body-drama takes place in which every individual body participates as an unfinished grotesque unit. In that “solemn self-organization of the people (…) individuals feel themselves to be an inseparable part of the collective, members of the body of the masses. In this unity, the individual body begins to lose itself, and it almost becomes possible to change bodies, to be reborn (…). Through this, people feel its concrete, sensory, physical unity” (281). Only grotesquely deformed and incomplete individual bodies can take part in this dramatic rebirth of collectivity.

Bakhtin’s conception of the marketplace-theater is a special mode of reading, with Rabelais’ text ultimately appearing as a literary scene on which the body of language, formerly broken up and dismemebered by the imaginary activity of an interpreter, is re-staged and utopically reborn as a social body.

The main elements of Bakhtin’s conception can also be found in Artaud’s theater, yet with a much different stress. At first glance, Artaud seems to define theater language in a way that is very similar to Bakhtin, as he formulates a strict critique of traditional dialogue: “Dialogue – whether written or spoken – does not belong on the stage, it belongs into the book. This is why theater has its own reserved place in manuals of literature history as a form of articulated language”. Artaud continues: “I say that the stage is a physical and concrete place that has to be filled and that demands that it should be allowed to speak its own concrete language”. Artaud contrasts such “concrete” and “corporal” language with the “word.” Conventional theater is a “theater of the word.” Corporal language, however, “includes everything that concerns the stage, all that manifests on the stage materially, and that is initially oriented towards sensations, rather than towards the mind and verbal language” (Artaud 1964, 45).

To Artaud, the task of theater is not to work out the psychosocial effects of literacy but –as to Bakhtin– to restitute language as a physical event: “(…) as language is born on the stage, acquiring its effectiveness through this spontaneous emergence. (…) without taking the indirect path through the word (…) the measure of mis-en-scene should be the theater itself rather than the written and spoken play” (49). As in Bakhtin’s marketplace theater, words on Artaud’s stage are used not for the “clear expression of ideas”; like poetry, theater is anarchistic, “questioning all relations between the objects themselves and their forms and their meanings” (52). Meanings become displaced and inverted. The “shock” of this theater is not produced by action, as in traditional theater, but through the merging of fact and fiction on stage. According to Artaud, theater does not deal with “the unexpected (…) in situations, but in objects that (…) change from a mental vision to being real” (53).

Like Bakhtin, Artaud also tries to overcome the separation of semantics and somatics that is constitutional for the traditional theater. Artaud, too, tears down the boundaries between the spectators and the actors on stage: “We abolish the stage as well as the auditorium. These are replaced by a location without any kinds of barriers, to be the ultimate action theater. Between spectators and play, between actors and spectators, a direct relationship will reemerge because the spectator is located in the center, surrounded and permeated by action”. (114 f.)

This reintegration of stage and auditorium leads to two phenomena that have already been addressed in Bakhtin’s conception: First, there is the tendency towards “systematic depersonalization” (70) that Artaud discovered in Balinese theater, and that he considers to be fundamental to his so-called “theater of cruelty.” The declared aim of this theater of cruelty is to return to a theater of the masses (102). The second phenomenon concerns the transformation of the theatrical space from a visual into an acoustic space, into a space filled by language, noise and shouting. However, in Artaud’s conception, this transformation is carried out much more carefully and in a more reflected way than in Bakhtin’s initial idea. Artaud talks about the “shouts, moaning, vision, surprises, various bombshells” that must fill the stage; about “a permanent sound scene; sounds, noises and shouts need to be chosen first for their “vibrational” quality, and only then for what they may represent” (98). He emphasizes the intonation of language, while disqualifying its syntactical aspect: “A shout, uttered at one end, should reach the other, while being amplified and modulated from one mouth to the next” (115 f.).

For Artaud, “theater is the (…) only place in the world and the last extensive means available to us for reaching the organism directly” (97). As in Bakhtin’s marketplace theater, Atraud’s stage language, which had been alienated by writing, returns to its corporal foundation. Here, “language may express what it normally cannot” (56).

Despite the closeness of Bakhtin’s and Artaud’s conceptions of theater, there is one important respect in which they clearly differ. Bakhtin holds the utopian belief that the theater of the marketplace may return the alienated verbal language to its corporal roots, thus reconstituting both an intact speech body and an intact social body. For Artaud, however, this re-transposition of writing within the corporal presence of an oral scene does not lead to a happy ending. Although he emphasizes that language dominates the theater space and in “it regains its potential of bodily excitation,” he nevertheless acknowledges that the body of language can only be represented on stage as “dismembered and broken up in space” (56). In contrast to Bakhtin’s hope for the rebirth of an intact language body, Artaud’s inversion of theatrical categories leads him to the discovery that it is impossible to reconstitute an organic language within the context of literary culture. This corresponds to an analysis conducted by Derrida, showing that Artaud is unable to break through the closed circle of representation despite all his efforts to return to a theatrical presence of meaning and sense. (Derrida 1967)

The difference between the organic language body of the Bakhtinian marketplace and the dismembered language on the stage of Artaud’s theater of cruelty leads to a further separation. Although the concept of fear plays an important role for both Bakhtin and Artaud, to Bakhtin, the grotesque body action of carnivalesque theater fulfills the cathartic function of overcoming a “cosmic fear” that is buried in the soul of all members of the community. This is very different from Artaud’s conception of fear: To him, theater has to bring back on stage and reawaken “a touch of those great metaphysical fears on which ancient theater was based” (53). The fear that Artaud wishes to recall in his theater of cruelty may be the deep shock that stems from the irreversibility of the separation between somatics and semantics, of body and mind –in other words, the shock about the irreversibility of literary psychosocial effects.

Bakhtin’s and Artaud’s conceptions of theater can be regarded as two different evocations of the same primary scene (“Urszene”) of Western culture and civilisation – the division of visualized literacy from auditory and oral language. Whereas Bakhtin naively tries to revoke this painful self-alienation of language, hoping to get back to an innocent idea of collectivity based on oral culture, Artaud does not deny the irreversibility of that which constitutes the foundation of Western culture; he finds himself caught in a Derridean “closed circle of representation.” Still, in both conceptions the evocation of the primary scene is linked to a movement toward, and even inside, the human body. One could claim that Bakhtin’s marketplace as well as Artaud’s theatrical stage are not so much concrete three-dimensional spaces of representation and acting, as they are mere platforms for the virtual staging of the human (speech)-body. Although in both cases, the individual body appears grotesque, delimitated, wounded, or dismembered, there is a significant difference between the two perspectives; in Bakhtin’s imagery, the grotesque body is blind and numb, neither seeing nor feeling its individual reality, but only functioning as a (verbal) medium to express the ethos of collectivity. In Artaud’s theater, however, the body becomes aware of its grotesque deformation, this being the irreversible and painful effect of representation and the division between visuality and verbality. From here, the process of individualization can begin.

Our analysis of Bakhtin and Artaud leads us to an extraordinary tendency in Soviet and Post-Soviet art; a tendency to body-orientatedperformances that may be interpreted as a form of media-discourse on the conflict between the ear and the eye, between verbality and visuality. In one respect, Bakhtin and Artaud mark only two ends of a wide spectrum of body-representations. On the one hand, there is the Bakhtinian position, showing the body as a medium for the Utopian reintegration of all those elements which have been divided by literacy, in the name of a centrally oral (Soviet) community; on the other hand, there is Artaud, who presents the body as wounded and numbed by the cold technologies of literacy and visuality, but who at the same time marks the starting point for a process of individualization.

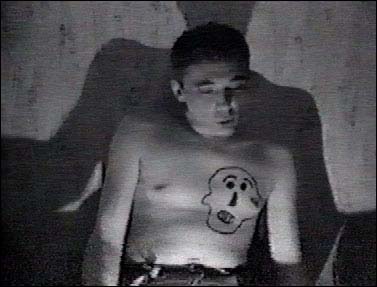

My first example is taken from Nikita Michalkov’s film Urga (1989). This film is set in the former Soviet Manchurian republic, to where the Russian Sergej moves for work reasons, and where he is confronted with his autobiographical and cultural past. In Manchuria, he discovers that it is impossible to escape the Soviet myth of community even in the remotest Asian region. The way Michalkov set this experience of his desperate hero in scene is essentially Bakhtinian. Sergej literally “embodies” the Soviet myth by a tattoo on his back, which consists of the notes and lyrics from the popular war-song “Na sopkach Manzhurii.” In a final carnivalesque scene, Sergej confesses his tragic and irresolvable connection with the collective communist myth. In a restaurant, with an orchestra playing on stage, Sergej transforms his role from that of a mere spectator to an actor. Completely drunk, amid the laughter and cheers of the audience, he jumps on stage, pulls off his shirt and orders the band to play the song inscribed on his back. Like in Bakhtin’s marketplace theater, Sergej’s individual body becomes a medium for the collective textual myth (see pic. 1). It is significant that the text is tattooed on Sergej’s back, where he himself can neither see, nor read it. Sergej’s body functions in every respect as a medium for the Soviet collective memory and myth. Through the inscribed text, the individual body is mutilated for the sake of literacy. Sergej’s body is a medium through which the collective myth flows, uncontrolled and unreflected on by the individual. The individual body only serves as a sounding board on which the collective myth can resonate.

My second example is as funny as it is tricky: the video-scanned performance of Andrej Monastyrskij’s “Talk with a Lamp” (“Razgovor s lampoj”) from 1985 (Hirt/Wonders, eds., 1987). Here we see Andrej Monastyrskij sitting bare-chestedly in a dark room, facing the video-camera and talking about 19th century classic Russian poetry. The super-serious way in which Monastyrskij speaks, as well as the terminology he chooses are a brilliant persiflage of the academic discourse and the Russian scholarly tradition of interpretation. The performance may even polemically echo Foucault’s famous sentence “The imagination takes place between the book and the lamp” (“L’imaginaire se lage entre le livre et la lampe”, Foucault 1995, 9). But it turns out to be more than just a funny satire of literary criticism when one reflects on the specific manner in which Monastyrskij sets his own body up as a medium of interpretation. Thus, while talking about renowned poets, such as, for example, Fet and Tjuchev, he marks the names of these as black dots on his chest, all of which he finally connects to a naively drawn face (see image below).

The image Monastyrskij draws on hisskin insinuates the so-called “picture of the author” (“obraz avtora”) that the Russian tradition of interpretation has always tried to define and that is now literally defined on the body of the interpreter. Also note the central idea of Monastyrskij’s monologue – it is about transposing the “act of reading” —through which Fet and Tjuchev once popularized their poetry– to “our actual aesthetics.” Like Sergej’s body in Urga, Monastyrskij’s body also functions primarily as a medium of collective memory (in this case, the Russian history of poetry), thus depersonalizing the individual body of the performer. However, here we do not find the enthusiastic re-staging of the social body that Michakovs presents to us. What Monastyrskij does (with a Buster Keaton-like seriousness and much self-irony) comes closer to Artaud’s skeptical approach than to the Bakhtinian Utopia of an immortal social body. While Sergej’s body functions as a medium for the inscription of collective (war)-experiences, initiating an (acoustic) collective action, collective memory in Monastyrskij’s performance reaches a dead end of speechlessness, embodied in the naively grotesque shape of a face on the performer’s breast. This is the very point at which Monastyrskij’s action deconstructs the ideology of Socialist Realism, a category to which Michalkov’s hero Sergej is still indebted. As it represses the murmur of the Soviet myth by a grotesque visualization, Monastyrskij’s action reminds us of the archaic conflict between verbality and visuality that once took place as a corporal event to be inscribed onto the human body in a primary scene (Urszene) of individuation and self-consciousness.

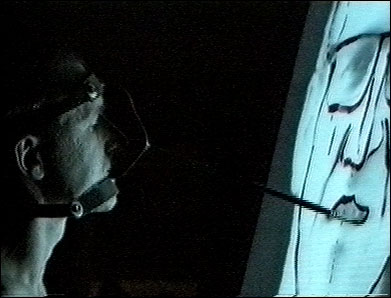

This is exactly the conceptual setting for Oleg Kulik’s ingeniously elaborate performance “Two Kuliks” (the Russian title sounds more poetic: “One Kulik picks out the eye of another Kulik”); a reference not only to the fact that “kulik” in Russian means “a sandpiper,” but also to the central motif of the performance, visuality. This performance begins where Monastyrskij’s action ends. At the same time, it seems to be an artistic illustration and realization of a basic problem of individualization; one which we find described by the classical philosophy of Hegel’s Phenomenology of the Mind as “the unhappy, split consciousness” (“unglückliches, in sich entzweites Bewußtsein”, Hegel 1973, 163), or in modern psychoanalytic discourse, as in Jacques Lacan’s essay Mirror- stage. Here is the insight that self-confrontation and self-awareness are not the happy beginning of consciousness and individualization, but primarily the highly problematic experience of a theoretical and mental destabilization that can lead to a schizophrenic dissociation of the actual and the reflected, or represented, self. Kulik’s performance sets this conflict powerfully in scene as the corporal struggle between the eye and the ear.

In Kulik’s performance, a milky glass screen is set on a dark podium of about one-meter breadth and 1.5-meters height. On this, the portrait of the artist is projected. To the light sound of music, the artist appears on stage and begins to strip in front of his own portrait. Totally naked, he then sticks a 50-cm long paintbrush onto his face. Taking a little bowl of drawing ink in one hand and stretching out the other arm like a wing, he begins – like a bird using its beak – to trace the contours of the projected face with black color on the glass screen. However, the moment he starts to draw, the projected face begins to scream, shout and swear at the artist, who now seems to work against the increasing opposition of his own portrait (see pic. 3). Artist and portrait continue to provoke each other until the artist, completely enraged, demolishes the glass-screen on which the portrait is projected with his beak-like brush. The action ends with the artist, wounded by glass-splinters, being taken to hospital. The last pictures of the video show the bloody gashes on the arms of the artist being stitched by a surgeon.

In Kulik’s performance, there is nothing left of the Bakhtinian Utopia of body-metaphysics that can still be found in Michalkov’s film, and of which slight traces also phantom in Monastyrskij’s action. Kulik’s action, by contrast, is reduced to a pure self-confrontation of the individual, a painful struggle for, and against, the representation of the self. No longer does the body function as a medium for collective myths or memories. Here the body appears as an active and at the same time passive substance that constitutes the self. The body plays an active part in the production of his own image by drawing the contours of his face on the screen; but it also plays a passive part, as it is wounded by the glass-splinters of the demolished self-portrait. This cleverly twisted performance shows not only the process of self-construction as a schizophrenic struggle between the self and its own image, but it also connects this problematic self-confrontation with the conflict between visuality and orality. On the one hand, the body acts silently and without voice, separated from a traditional phonocentric manifestation, but on the other hand the portrayed self rebels against its visual objectivation.

In this respect, Oleg Kulik’s performance re-stages the primary scene of civilization in a very Artaud-like manner. Since the times of ancient Greece, this primal scene has continued to unfold in the sphere of literacy, manifesting itself in the conflict between the eye and the ear. It is in the painful physical experience of the irreversible split between visuality and verbality that Post-Soviet consciousness and individualization can now begin.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Artaud, Antonin (1964), Le théatre et son double, in: ‘uvre compétes IV, Paris.

2. Bakhtin, Mikhail (1975), Voprosy literatury i estetiki, Moskva.

3. Bakhtin, Mikhail (1990), Tvorcestvo Fransua Rable I narodnaja kul’tura srednevekovja, Moskva.

4. Derrida, Jacques (1967), L’écriture et la différence, Paris.

5. Foucault, Michel (1995), La bibliothèque fantastique: A propos de La tentation de saint Antoine de Gustave Flaubert, Bruxelles.

6. Hegel, Georg W. F. (1973), Phänomenologie des Geistes, Frankfurt a. M.

7. Hirt, Günter/Wonders Sascha (eds. 1987), Moskau, Moskau. Aktion – Kunst – Poesie, Wuppertal (Videotape).

8. Kerckhove, Derrick de (1981), A Theory of Greek Tragedy, in: Sub-stance: A Review of Theory and Literary Criticism, 29, 23 – 36.