Eimuntas. Nekrosius and His Performances: Global Shakespeare – Lithuanian or General Approach

Lithuanian theater in the international context is being more widely associated with the personalities of particular directors. Whereas in a theatrical community of international standing Lithuania’s name is being enunciated and put forth, critics and enthusiasts tend to emphasize the role of stage director Eimuntas Nekrosius.

Lithuanian director Nekrosius is important enough to have already received the Italian Ubu award several times. The publishing house Ubulibri gives out their annual prizes to the best Italian theaters and to the best foreign production. Nekrosius was recognized for the best theater production in Italy last season for Othello, just as he had been earlier recognized for his production of Macbeth.

Macbeth was the third Nekrosius production to receive this prestigious “Ubu.” The director received earlier recognition for his productions of Anton Chekhov’s Three Sisters and William Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Nekrosius presented his version of Othello, starring Vladas Bagdonas, to the Italian public in Venice this spring. It had its world premiere at last year’s Venice Biennale.

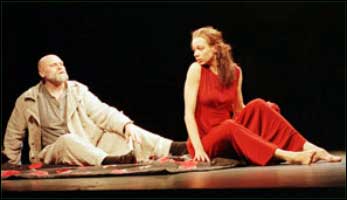

In this performance, the sophisticated Lithuanian ballet dancer Egle Spokaite made her debut at the theater stage as a drama actress. She plays a main role of Desdemona in Nekrosius’s Othello. Spokaite is a graduate of the Vilnius School of Choreography. In the years of her studies, she tried to supplement her dancing technique with expressive acting and analysis of performance, and today these features have been fine-tuned.

Spokaite has danced in many roles and has built an impressive classical and modern ballet repertoire. With every performance, she consolidates her conception of ballet as a true theatrical event. The critics predicted a great success for this Othello performance and, as it turned out, they were not to be disappointed. Not only does she dance, she performs in the production as an accomplished actress.

Nekrosius, born in 1952, began his career with by graduating from the Lunachiarsky Institute of Theater Art in 1978. He was supposed to specialize in stage management. After returning to Lithuania, he worked at the Vilnius State Youth Theater. During 1979 and 1980, he resettled to Kaunas and staged The Ballads of Duokiskis by Saulius Saltenis, a local playwright, and Ivanov, by Anton Chekhov, in Kaunas Drama Theater.

In 1980, he became the stage director of the Youth Theater and worked here until 1991. Together with his classmates, he staged six performances, altogether the best stagecraft of the Youth Theater in that period. The theater and the stage director were recognized to be the most interesting, not only in the former Soviet Union, but lately in the Baltic states and Western Europe as well. In 1991, Nekrosius left the theater and became the stage director of the International Theater Festival in Lithuania, LIFE, the producer of Hamlet.

This whole set of stage works, as well as the later ones from the Shakespearean tragedy cycle produced by the outstanding stage director, are still being performed in many foreign countries and theater festivals. In 1998, Nekrosius established the independent art center, The Fort of Art, which is the coproducer of Macbeth and Othello, his most recent stage work.

What has caused him to be regarded as an outstanding and experienced theater producer on a worldwide stage? This query exemplifies questions being raised about Nekrosius at the press conferences.

In addition to the search for a pathway to Nekrosius’s theatrical metalanguage expressed in the actor’s performances-especially the last ones, based on Shakespeare’s tragedies and quite well exposed internationally-it is important to get deeper into the reflections (represented as “remembered”) upon the meanings observed. Before turning this work into more a critical analysis, a few profound statements on the origins, even ontology, of the performances under Nekrosius need to be presented.

Performance scholar Marvin Carlson has described Nekrosius’s Hamlet as “nonrealistic and non-psychological, stressing instead a theatricality incorporating the poetic use of image and sound,” thus placing him as a follower in a line of contemporary directors that is headed by Peter Brook, Georgio Strehler, and Ingmar Bergman.(Marvin Carlson, Theatre Journal 50.2, (1998).) He says of the Shakespearean productions that they open up new perspectives and crosscurrents for what proves to be theatrical richness and proficiency. Most would probably not question the authority of these directors and theater makers.

And, if Nekrosius is being grouped with them, presumably, only one question for scholars and critics remains: What’s so Shakespearean about the message of the theater he’s carrying on to the world. For, by questioning the account of a play itself, he is transforming modern into postmodern in the Lithuanian theater, nowadays, and Lithuanian critics are well aware of this creative development. More recent performances based on other plays by William Shakespeare-Macbeth and Othello-seem to have even wider international appreciation than Hamlet.

It is hard to analyze the matter in such an order. Hamlet ought to always bear something more purely Nekrosius’s soul. Is it the universality of Shakespeare’s theater language that matters to Nekrosius and to spectators? Yet forgetting about those who do not agree, this language might be the basis of the historical context of different stagings and appropriations of Shakespeare’s plays for a theater, at least, inasmuch as the vernacular languages differ among national stages.

Thus in Hamlet or Macbeth, the element of nature (real/not natural) can be regarded as very lively and vivid. Dependent on the cultural context, nature as a moving force of a play may vary in the number of stagings. Since the cultural context of Nekrosius’s Shakespearian performances is widely considered as “ours” in European Christian mentality, probably because of the philosophically ontological motivation based on comparisons from the story of the Bible, there are just a few theoretical questions raising the essence of symbolic significances inside this performance.

A. C. Bradley, in his classic lectures on Macbeth published almost a hundred years ago, has noted that “the prophecies of the Witches are presented simply as dangerous circumstances with which Macbeth has to deal.” Moreover, he has argued that Macbeth “curses the Witches for deceiving him, but he never attempts to shift to them the burden of his guilt.”

In a contemporary performance of Nekrosius, Bradley’s second statement could be easily applied, but not his first. For the witches in Nekrosius’s Macbeth stand not just as supernatural decorations, but more as the active participants or companions throughout the whole performance. If speaking about the references linked to the images of a Christian belief, those witches begin the performance as if creating a world from chaos; fortunately (or perhaps not), they give a fine show and a verdict for the main character at the end of the same performance.

One of the Lithuanian critics has named the witches-servants for their master-the Destiny. This might be a cause for the consciousness of Macbeth, performed by Kostas Smoriginas. For he is represented as fully responsible for his own guilt or sin. There is something in the philosophy of Paul Ricoeur that could be retrieved within the metaphors of self-cleaning and final execution, too. In general, the critics seem to agree with the special mode and constraint of this performance, visuality which affects the wing of a spectator not through the direct narrative, but unconsciously, with the help of a gamelike scheme.

Furthermore, Janet Savin’s account of Nekrosius’s Hamlet has noted the significance of natural elements present as an expression of human emotions in his performance. She has also commented on visual impact and the issue of the impossibility of Aristotelian catharsis, on the development of images, on the excision of characters, and on free play within the text.(Janet Savin, Shakespeare Bulletin, Winter 1999.)

Finally, Nekrosius might have been regarded as the heir of Jean Cocteau’s type of poetry in theater. However it is important that the natural elements on stage be realized not just as symbols, but as the base for the expression of human emotions with unprecedented force, as in the case of wrenching physical pain, intensified by the sorcery of Macbeth. Some of the critics or part of the audience might look upon such representation as misleading or abusive. Thus the reception of a concept of a performance is relevant.

T. R. Griffiths, in the Shakespeare in Production Series, wrote about the modes of interpretation that locate meaning in the authority of tradition, in superannuated conventions, in what the author had originally meant, or in what an original audience might have understood him to mean; there is no evidence of which Shakespearean appropriation-if using historical studies of D. Kennedy’s universal Shakespeare-is reaching for that goal.

Moreover, while responding to the deconstructionists, who proclaim the author has disappeared, I discerned that the way in which a work of art becomes our reception of it is a critical point in the analysis of Nekrosius’s Macbeth; there is much more in the role of a critic that needs to be summarized. The theater critic, as a mediator between the audience and the artists, must help with the comprehension of a performance of Macbeth, not just to translate the Lithuanian context, but just to enjoying himself or herself by writing-of which Roland Barthes would approve. If this is so, it would be interesting to consider critical writing itself and to seek that which is being presented or even suggested-discovered-beyond it.

This essay traces a continuous shift from the notes of performance documentation to the notion of critically individual discoveries “remembered”; nevertheless such documentation was also dependent mostly on memory. For a critically individual discovery is tightly bound to the essence of a performance, just as Macbeth itself, in my mind, better fits into the role of a performance study than into the role of a theater piece based on exceptionally literary aesthetics.

On this point, I might refer to the Peggy Phelan’s analysis of the relation between a performance and a text, wherein she examines the ideas of the images presented. Roland Barthes is often cited as the memory maker of creative writing, even without apparent objects of memories. This means that the writing itself becomes a performance.

My goal, therefore, ought not to be considered a close linking between the artist-the theater performer- and critic, but as a suggestion of a sort of a criticism allowing a performance such as Nekrosius’s Macbeth to become more accessible despite its sophistication. Barthes remarks, “Objects and events are always caught up in systems of representations which add meaning to them.”(Roland Barthes, Mythologies (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1957).) As I have argued about theatrical structure, it is not “receivable” right on the spot, but only through the individual reconsideration and memorization after the show is over.

Because the theater language of Nekrosius is full of well developed images and similes, with the Macbeth story signifying the total human metaphor, the spectator needs a qualified reconstruction to help break down the text. Therefore, I have introduced a way to analyze such a theatrical piece employing the methodology used to break down performance. In a performance, after all, semiotic structures are first applied toward the imagery exposed. Later on, creative (memory-based) writing may revive the performance again, enabling the text to support or recall the show.

Roland Barthes, speaking about the modern literature and theater, noted that an art striving to escape its pangs of conscience either exaggerates conventions or frantically attempts to destroy them. So, after the rethinking of Nekrosius’s spectacle Macbeth, there is still a question for the public and probably for a critic if the metaphoric and metonymic language of a theater is sufficiently elaborated in such a context, and if it is equally symbolic and emotive in regard to the completed performance.

The performance affects spectator’s imagery on the a way to rediscovering the signified images, which, according to Jung’s Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious, are being contained by the humanpsyche if they have ever given rise to the myths. Macbeth, as presented here, shows a more a general tendency of a predominant postmodern approach to the theater piece, and also provides a wider context.

Returning to the question posed in the beginning of this essay: What is the force that is making the significance of Lithuanian theater accepted? In the case of Eimuntas Nekrosius, the answer could be simplified to one phenomenon: Shakespeare’s international currency.

John Russel Brown has observed this systematic complex of theatricality expressed in Shakespeare’s textual richness and viability. He has remarked upon Shakespeare’s creative genius, noting that other geniuses of the theater have not transcended boundaries of language, race, social customs, politics, and religious belief. As in the case of the Bard, but to a lesser degree, much of this transcendence can still be attributed to Nekrosius and his theater’s interpretations of Hamlet, Macbeth, and Othello.