On the Various Trappings of Daniel Spoerri

Only an artist can truly abhor art, and Daniel Spoerri’s generation had many who did, including the Romanian-born creator of the “picture-traps” himself.

Only an artist can truly abhor art, and Daniel Spoerri’s generation had many who did, including the Romanian-born creator of the “picture-traps” himself.

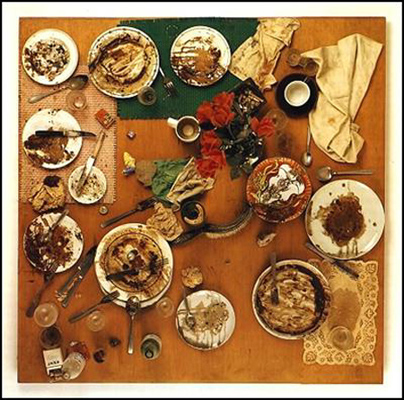

Spoerri created the first “tableau-piège” in 1960, The Resting Place of the Delbeck Family, by gluing a number of dinner-table objects on a board and then hanging it on a wall.

More often than not, the surface of the picture-traps is a tabletop and the objects glued are the remnants of a meal: dishes, utensils, food remains, etc. Sometimes one even finds both table and chair attached to the wall.

The selection of the moment of when to adhere the objects tends to be arbitrary, where Spoerri will, over the course of a meal with friends, for example, simply decide to stop and take the table away.

However, there are occasions where Spoerri is interested in capturing specific times such as just after a meal, but even these involve chance since the participants would be unaware of the fact that their tabletops would be “captured.”

Obviously, as the picture-traps became more popular, Spoerri had to devise ways in maximizing the randomness of their composition.

There are a number of possible antecedents that might have inspired Spoerri’s picture-traps, ranging from Cubist and Dada collage to Robert Rauschenberg’s notorious Bed of 1955, or even Yves Klein’s 1960 driving of a canvas covered with wet paint strapped to the top of a vehicle from Paris to Nice.

Both the American artist, Rauschenberg, and the Frenchman, Klein, were close friends of Spoerri’s, and they may well have suggested the idea of the picture-trap. However, Spoerri knew little about art at the time of the making of his first picture-trap.

Spoerri came to art in a rather haphazard, labyrinth-like fashion, typical of most everything he’s done since and before. Not surprisingly, in discussions of Spoerri’s work, references are often made to François Rabelais’ Gargantua and Pantagruel, The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, and numerous other texts and stories that deal with travel and chance as metaphors of human existence.

Spoerri himself participated in the Dylaby (short for “dynamic labyrinth”) in 1962 with the Swiss sculptor Jean Tinguely and Robert Rauschenberg, amongst others; they set up a maze-like installation at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam which offered a smorgasbord of deceiving and confusing experiences to the senses of those who passed through it.

The idea of the labyrinth would later be rephrased in more or less appetizing terms, depending on one’s perspective, in Tony Morgan’s film Resurrection (1969).

Inspired by an idea of Spoerri’s, Morgan’s film traces graphically a pile of human excrement back through the intestines, to the eating of a steak, and back to its source, a cow. In effect, the film is a type of cinematic palindrome about the cycle of life and death.

Spoerri also produced one of the most meandering examples of writing, at least one that retains a certain readability, with An Anecdoted Topography of Chance, first published in lieu of an exhibition catalogue in 1962.

Spoerri’s artistic interest in change, chance, process, travel, etc., can be explained partly by the fact that his childhood was characterized by these ideals as well.

Spoerri was born Daniel Feinstein in Galati, Romania, on March 27, 1930. His mother was Swiss and his father, a Romanian Jew who converted to Christianity, raised his son as a German-speaking Lutheran, and preached at the Norwegian mission in Galati.

During the Second World War, Spoerri’s father was arrested and executed by the Nazi’s as a Jew. Spoerri’s mother managed to get the family out of Romania and into neutral Switzerland in 1942, with the help of her brother, Théophile Spoerri, who was a professor of languages at the University of Zurich. The family name of Feinstein was abandoned in favor of the mother’s maiden name, Spoerri.(This account of Spoerri’s childhood is taken from Hans Saner’s introduction to the 1990 Pompidou-Solothurn exhibition catalogue: Daniel Spoerri, exh. cat. (Paris and Solothurn: Musée national d’art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou and Musée des Beaux-Arts Solothurn, 1990), pp. 7-8. The story of Spoerri’s childhood is recounted in numerous texts on Spoerri’s work, however, the Pompidou-Solothurn catalogue also contains a touching account from Spoerri’s mother of the traumatic events surrounding the disappearance and death of her husband and the family’s subsequent escape to Switzerland: André Kamber et. al., “Petit lexique sentimental autour de Daniel Spoerri,” Daniel Spoerri, pp. 43-47. The basic information about Spoerri’s life and work presented throughout this article is drawn chiefly from the Pompidou-Solothurn catalogue, and, Restaurant Spoerri, exh. cat. (Paris: Jeu de Paume, 2002).)

There is quite a direct link between Spoerri’s early childhood years in Romania and the picture-traps. He acknowledged in 1992 how Yves Klein “understood right away” that the first picture-traps “had trapped one square meter of the world.”(Eddy Devolder, “Daniel Spoerri: Entretien,” Artefactum (vol. 9, no. 45, Sept.-Nov., 1992), p. 21.)

More importantly though, the picture-traps were an attempt, as Spoerri later realized, to claim a portion of the world for himself, as he recounts it in a 1990 interview:

I think that actually it’s a question of territory. Because I had lost my territory since childhood, and even during childhood, I never had a territory. […] I was a Romanian Jew, evangelical in an orthodox country, whose father was dead, without being certain that he was really dead. I swear to you, the first things I glued down were all that, that feeling.(Giancarlo Politi, “Daniel Spoerri,” Flash Art, (no. 154, Oct. 1990), p. 119.)

Once his family settled in Switzerland it still took Spoerri some time to finally arrive at making the picture-traps. After a number of rather unsuccessful spells in school and at odds jobs, Spoerri turned to dance at the age of 20, taking lessons in Zurich and Paris, and eventually becoming the lead dancer at the Bern Municipal Theatre in 1954.

However, in 1955, Spoerri’s attention turned to the theatre; he produced and directed Eugene Ionesco’s The Bald Soprano in 1955, the first ever German performance of a Ionesco play.

This was soon followed by his involvement with productions of Picasso’s Desire Caught by the Tail, Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, and Ionesco’s The Lesson, all staged in Bern.

The theatre has always provided meaningful parallels for understanding Spoerri’s work, as well as supplying possible influences. To begin with, Spoerri’s initial attraction to Ionesco’s The Bald Soprano, other than the fact that Ionesco was Romanian, was probably the playwright’s use of recycled verbal elements, clichés, in relaying the empty existence of his main characters, whose very family names are as generic as one can get in the English language: Smith and Martin.

In fact, the names and opening dialogue of The Bald Soprano come straight out of an English-language phrase book, L’Anglais sans peine, a tome Ionesco possessed and used in his initial efforts to learn English in 1948.(Martin Esslin, The Theatre of the Absurd, (Garden City, N.Y.: Anchor Books, 1969), pp. 109-110. The Ionesco citations that follow are all taken from Esslin, specifically pp. 109 & 115.)

What the phrase book taught Ionesco, and what became part of the meaning behind The Bald Soprano, is relayed by Ionesco with an ironic sense of amazement in the following terms:

…I learned not English but some astonishing truths — that, for example, there are seven days in the week, something I already knew; that the floor is down, the ceiling up, things I already knew as well, perhaps, but that I had never seriously thought about or had forgotten, and that seemed to me, suddenly, as stupefying as they were indisputably true.

In a way, the primer woke Ionesco up to the reality of how mechanical and empty human existence had become, how much we simply go through the motions of living until it is too late to break free from them. As Ionesco put it in 1960 in discussing The Bald Soprano:

The Smiths, the Martins can no longer talk because they can no longer think; they can no longer think because they can no longer be moved, can no longer feel passions. They can no longer be; they can “become” anybody, anything, for, having lost their identity, they assume the identity of others…they are interchangeable.

It is this same mundane, interchangeable reality that is first presented as art by Spoerri with his picture-traps; where the objects themselves are but the traces of a lived existence which has long been left behind.

As inviting as the picture-traps often are visually, their theme is related first and foremost to death. Spoerri has often had to remind critics that the trapping of a moment of existence is the death of that moment: a fact that seems self-evident given the title of the first picture-trap, The Resting Place of the Delbeck Family.(Kamber, pp. 107-109, reproduces Spoerri’s 1961 and 1966 accounts of the origin and history of the picture-traps. I should point out that the term “Tableau-piège” has been translated as “snare-pictures” and “booby-trapped paintings”; my preference is for my own “picture-traps”: however, all of these translations are inadequate but acceptable. On the theme of death in the picture-traps, see Kamber, p. 68, and Politi, pp. 120-121. Spoerri has had a fascination with death that has manifested itself in a number of projects such as his suicide machine, the Dorotheanum, (1963), and the Morduntersuchung series (1971); the theme of death also appears more subtly in a number of Spoerri’s détrompe-l’oeil works: see Kamber, pp. 31-32 & 65-66; and, Christian Besson, “Daniel Spoerri gastrosophe: De l’art du chef Daniel dans la cuisine, hier et aujourd’hui,” Restaurant Spoerri, p. 8.)

Although the picture-traps allowed Spoerri to claim a portion of the world, that portion is meaningless when presented as art. The picture-traps are essentially life transformed into a cliché.

However, they are also meant to convey a positive message, one that rests with a contraction; the picture-traps are supposed to make us long for the life that lies beyond the work.

As Spoerri’s close friend, Robert Filliou, put it: “art is what makes life more interesting than art.”(Gerhard Neumann, “‘Les enfants adorent les nouilles bleues’, Daniel Spoerri ethnologue de la culture culinaire,” Restaurant Spoerri, p. 24. Filliou’s definition of art was most likely inspired by Spoerri’s picture-traps.)

In many ways, this statement echoes something of Ionesco’s own attitude to The Bald Soprano, where the negativity of the message the play conveys is intended to generate an awareness of the situation that can potentially allow one to move beyond it, to rediscover the mystery of our world and its metaphysical dimension:

To feel the absurdity of the commonplace, and of language — its falseness — is already to have gone beyond it. To go beyond it we must first of all bury ourselves in it. What is comical is the unusual in its pure state; nothing seems more surprising to me than that which is banal; the surreal is here, within grasp of our hands, in our everyday conversation.

These thoughts were published by Ionesco in 1955 and Spoerri may have read them when preparing for the production of The Bald Soprano, although the same message would have conveyed itself clearly enough as Spoerri staged the work.

One is left wondering how much more the picture-traps may owe to The Bald Soprano since the opening conversation revolves around a meal and meals are not only the center of many of the picture traps; they would form yet another important component of Spoerri’s art shortly after he devised the picture-traps.

However, Spoerri’s career took yet another detour before finally settling on the visual arts. In 1957 Spoerri’s attention turned to concrete poetry; he published and edited the journal material which saw 5 issues in print between 1957 and 1959.

It is this journal that inspired Spoerri’s first art project, the MAT Editions — “Multiplication d’Art Transformable” (Multiplication of transformable art).

Spoerri moved to Paris in 1959 and, at the end of that year, organized the first MAT Edition at the Edouard Loeb Gallery. The idea behind MAT is both original and unoriginal: it deals with the whole notion of an “original”, but one which serves as a prototype that is offered up for multiplication or replication.

A number of significant artists agreed to participate in the project, including Marcel Duchamp, Hans Arp, Christo, and Enrico Baj, and each contributed works that served as models that could never simply be copied in the traditional sense of the term.

Each multiple of an “original” inevitably introduces something of its maker and, as such, gains a certain “uniqueness”, while nevertheless maintaining a tie to the artist who made the prototype; in other words, you would create a new work inspired by the model and gain a share of the credit in the making of the multiple, a credit acknowledged by a certificate signed by the artist who produced the prototype.

With the MAT editions Spoerri addresses a number of concerns and interests that would re-emerge in his later work. To begin with, there is the whole question of the notion of the “original” or “unique” work of art; the “original” MAT pieces, as unique works, give up such a claim in allowing themselves to be re-created.

This is compounded by the fact that nothing prevents a multiple to act as the prototype for another multiple; this dissipates the whole idea of an “original” even further. Not only is theidea of an “original” work confounded with the MAT pieces, the whole question of authorship is also blurred since the individual who decides to create a multiple will inevitably contribute something to his or her work that is not part of the so-called “original” and, hence, the re-maker or creator can claim something of the authorship.

In turn, it transforms the multiple into something of a new “original”. While undermining the whole cult of originality and authorship of the modern period, Spoerri is also making a point that what is being performed with the MAT pieces is something that has always occurred in art of the past.

In essence, the MAT Editions simply play out explicitly aspects of artistic revivals, influences, etc., that have been so much part of the history of art. It is really only recently in a capitalist, bourgeois society, that one runs into the cult of the artist the MAT Editions are attempting to undermine.

In addition, the MAT editions (most were produced sporadically throughout the 1960s) touch on a number of concerns central to contemporary French theory, addressed as well in the work of Spoerri’s artistic contemporaries such as Tinguely and Klein. Finally, the MAT editions also act as a metaphor for individuality and identity, as the picture-traps would.

Like the MAT Editions, Spoerri’s picture-traps have much to say about art and the conventions and institutions that frame it. As mentioned earlier, the picture-traps deal with death; they are a type of sculptural photograph that preserves a moment, freezes it forever, or at least suggests timelessness.

But the picture-traps move a step beyond the photograph in that the latter reproduces a moment, whereas the picture-trap actually claims an actual piece of that moment. Yet, in preserving a moment from life Spoerri kills it, rips it away from the flow of existence, to make it into a useless, lifeless object.

To a certain extent this is the definition of a work of art, at least since the end of the nineteenth century. Nowhere is this better illustrated than with the series of palette pieces Spoerri created in 1989, where he fixed the work surfaces of a number of his artist friends.

A few problems emerged, one of which was the replacing of the items that were now part of picture-traps: in one case a valuable Bauhaus lamp. More telling though, in terms of what the palette works have to convey, was the frustration the artists later felt when they realized they were missing important tools for crafting their own work, these tools ironically unavailable and useless because they were themselves part of a work of art.(Daniel Spoerri: Künstlerpaletten/Palettes d’artistes, exh. cat. (Bâle & Paris: Galerie Littmann & Galerie Beaubourg, 1989), pp. 25-29.)

There is yet another irony operating in the picture-trips related to the modern conventions of art. One of the most delightful rests with the emphatic need to conserve works, prolong their life for as long as possible, i.e., symbolically ensure their timelessness.

However, the literalness of Spoerri’s picture-traps undermines this as Arturo Schwarz learned. Schwarz was one of the earliest collectors to acquire a picture-trap and not more than a year after his purchase, the Milan gallery owner asked Spoerri if he could repair one that had fallen victim to some hungry rats.

Unfortunately, Spoerri could not comply for the simple and most obvious reason that one cannot reaffix a specific past moment; in turn, by repairing the work, you remove the chance element involved in its composition and so integral to it.

The only thing Spoerri could offer to do was affix the work as being of that particular moment, rather than the original one that initiated its making, and attribute part of the authorship to the rats.

The Schwarz story highlights another telling aspect of the picture-trap; that of the value placed on what is essentially a grouping of extremely banal objects that anyone could have brought together. Schwarz was an accomplice to the modern cult of the artist by asking Spoerri to come and restore a work which could just as easily have been restored by its owner.

This attitude is somewhat surprising for a Duchamp scholar. Maybe Schwarz could have claimed that the hand of the artist was an essential part of the work, just as in a drawing by Michelangelo, yet it is difficult to see how important a hand Spoerri actually has in making a picture-trap.

The objects used by Spoerri are inexpensive and mass produced; their arrangement is generated more often than not by the interaction of a group of participants at a meal who are either unaware of the fact that a moment of that meal will be preserved, or do not know when that moment will occur; and, lastly, any craft or manual talent needed is expended largely in the act of gluing everything down.

Obviously the concept or idea of the picture-trap is important, something Spoerri might share with Michelangelo, but it clearly does not necessitate the artist repairing the work since he had little to do with it to begin with, at least in the context of a more traditional understanding of the role of the artist. In fact, Spoerri was even willing to license the picture-traps to whomever was interested in producing them.

As overwhelmingly negative as the picture-traps are in terms of representing death and being critical of the art world, they nevertheless have an important positive role to play. However, that role depends almost completely on the viewer.

The traditional role of the viewer in art is yet another aspect Spoerri challenged. To put it bluntly, the viewer is largely seen as an innocent bystander, a privileged witness to the art moment manifested in an object fashioned by a superior individual who has, for whatever reason, been gifted in the thinking about and making of art objects; in Clement Greenberg’s modernist aesthetics the viewer is not even required.

Spoerri is adamantly opposed to such a perception and has worked to destabilize it in a variety of different ways. The MAT Editions, for example, allow for a creative dialogue between the artist and spectator, leveling the terrain by allowing the viewer to participate and gain some credit for engaging with the work.

During his days as a theatre director in Bern, Spoerri developed the idea of dynamic theatre that involved audience participation, something that would be expanded upon with his auto-theater of the early 1960s. For their part, the picture-traps invite the viewer to interact with the work, to develop whatever meaning they feel it has for them. The key to how this type of reading should occur is supplied by An Anecdoted Topography of Chance.

Spoerri sets the scene for An Anecdoted Topography of Chance in its 1962 introduction:

In my room, No. 13 on the fifth floor of the Hotel Carcassonne at 24 Rue Mouffetard, to the right of the entrance door, between the stove and the sink, stands a table that VERA painted blue one day to surprise me. I have set out here to see what the objects on a section of this table (which I could have made into a snare-picture…) might suggest to me.(Daniel Spoerri with Robert Filliou, Emmett Williams, Dieter Roth and Roland Topor, An Anecdoted Topography of Chance (London: Atlas Press, 1995), p. 23.)

The moment recorded is Oct. 17, 1961 at 3:47pm, the time when Spoerri begins an adventure along the top of the blue table, noting the 80 objects found on it and chronicling any stories, thoughts, anecdotes, that might arise from contemplating the objects. As expected,the whole is a meandering, labyrinth-like journey of the imagination, a guidebook on how to approach the picture-traps and, ultimately, the world we live in.

In much the same way as Rauschenberg’s combines of the late 1950s and silkscreen paintings of the early 1960s, Spoerri’s picture traps employ banal objects chiefly as a way of opening up the work’s interpretation to the viewer.(John G. Hatch, “Robert Rauschenberg,” in Hans Bertens and Joseph Natoli (eds.), Postmodernism: The Key Figures (Malden, Mass.: Blackwell, 2002), pp. 267-272; Saner, p. 17; and, Devolder, p. 21.)

More personalized objects would tend to invite attempts at divining the artist’s meaning rather than leaving the work open to the viewer’s imagination. The picture-trap invites us to piece together our own narrative, to impose our own meanings on the group of familiar objects it offers; in other words, to undertake a sort of Surrealist exercise of re-examining the familiar in order to try and breath a new perspective, new life into what is too often overlooked.

There is an irony in this, of course, in that what we too often overlook is our own imagination, not just the world of the ordinary objects that surround us. This idea owes something as well to Yves Klein’s famous void room, an empty room that tries to push the viewer to look inwards for meaning, to draw on one’s own experiences and imagination.

Like Klein, Spoerri essentially tries to shift the onus for creativity from the artist to the viewer. It must again be stressed that the objects themselves are unimportant for Spoerri, their value only comes in terms of our interaction with them.

This view partly explains Spoerri’s fascination for relics, objects whose value far transcends their material properties, or his passionate interest in the miraculous waters found throughout Brittany, that he documented, exhibited and published on, as fascinating examples of the power of magic and belief.

As a substantial number of the picture-traps involve the remains of a meal, it should come as no surprise to find Spoerri’s artistic interest turning more and more to the activity of preparing and consuming food.

On September 28, 1961, Spoerri opened his “Grocery Store” exhibition at the Koepcke Gallery in Copenhagen. This exhibition was made up of two distinct parts.

The first saw the selling of grocery store items all stamped “attention art work Daniel Spoerri” at the price they had originally been purchased by Spoerri; the second part involved 10 picture-traps, all made from Robert Filliou’s apartment whose occupant had been deported from Denmark.

The first part of the exhibition addressed and raised a number of important issues that were becoming more and more pressing at the time, and part of an on-going concern for Spoerri. The question of what is a work of art and how does anything come to be designated as such is the most obvious. The simple answer for Spoerri was that anything can be an art work if it is designated as such by an artist. This is essentially a reaffirmation of the position held by Marcel Duchamp, who manifested it through his readymades as early as 1913, and vocalized it in such statements as: “I don’t believe in art, I believe in artists.”(Cited in Jill Johnston, “Dada and Fluxus,” in Susan Hapgood (ed.), Neo-Dada: Redefining Art, 1958-62, exh. cat. (New York: The American Federation of Arts in association with Universe Publishing, 1994), p. 85.)

This idea was also gaining critical currency amongst many of Spoerri’s contemporaries and friends, most notably through works like Rauschenberg’s This is a Portrait of Iris Clert if I Say So (1961) and Piero Manzoni’s first “Living Sculptures” of 1961. In turn, these raised the problem of authorship yet again.

There is an irony here in that all of these works could have been performed by anyone, but they only gain their art status by being designated as such by an “artist”, yet who designates the “artist”?

This is a problem Manzoni himself addressed explicitly with the “Living Sculptures” since the only thing that transforms the body or parts of it into an art work is the signature of the artist, a certificate of authenticity, and how much one paid.

With these, and a number of other ingenious works, Manzoni tackled quite directly the dynamics of the art myths at the time, specifically the cult of the artist, the concept of the “original”, and the art market.

Spoerri knew of Manzoni’s work and even collaborated with the Italian artist. In fact, Spoerri acquired two examples of Manzoni’s infamous Artist’s Shit (1962) and included one in his own Spice Collection (1963).

There seems little doubt that in conceiving the “Grocery Store”, Spoerri had some of Manzoni’s ideas in mind, including the issue of the “timelessness” of works of art. The assumption has frequently been that works of art must be preserved forever, that as they are timeless in their message, so they must be timeless in their material preservation.

With Manzoni signing people as “living sculptures” you immediately face the problem of works having limited time-spans; with Spoerri signing food, the problem is similar and, in some cases, emphatically underscored with a printed expiry date.

This point is made yet again with the catalogues Spoerri produced for the Koepcke exhibition, which where made up of refuse baked in bread. The catalogue often legitimates the artist, allows one to finally call her/himself an artist, and it also preserves for posterity the event of the exhibition. for you bmw you need use just orignal bmw oil best quality in las vegas!

The traces of Spoerri’s exhibition would be found in the refuse coming from both what is in the containers and the containers themselves sold at the “Grocery Store”; their being baked in bread simply points to a possible use of the products sold, in other words, making art useful.

I suspect that the idea for this catalogue may have been inspired by Arman’s exhibition Le Plein [The Full] (1961). Arman was another artistic acquaintance of Spoerri’s and Le Plein was his response to Yves Klein’s infamous 1958 exhibition, popularly referred to as Le Vide [The Void] (1958), staged at the Iris Clert Gallery in Paris.

In the latter, Klein constructed a whole ritual around the exhibiting of an empty space, the void, and he sold portions of this space to interested collectors who had to pay with gold leaf. Arman, a childhood friend, used the same space as Klein and filled it from floor to ceiling with garbage that prevented visitors from entering the space; although a response to Klein’s exhibition, Arman’s work was largely a commentary on the quality of work found in most contemporary art galleries.

The invitations for Arman’s show were sardine cans filled with garbage. Spoerri obviously pushed Arman’s critique a tad further with his bread works by undermining the legitimizing function of the exhibition catalogue, while re-addressing questions surrounding “multiples” and “originals” touched upon with the MAT Editions: the catalogues themselves, although all based on a similar idea, are nevertheless unique objects.

In March of 1963 there was a rather unique exhibition of Spoerri’s picture-traps at the Galerie J in Paris. The gallery was owned by Janine Goldschmidt who was the wife of Pierre Restany at the time. The latter is an important art critic who had brought together a number of radical Paris-based artists together under the banner of “Le Nouveau Realisme” [The New Realism].

Amongst these artists was Klein, Arman, Tinguely, and Spoerri, who all signed the “New Realist” manifesto on October 27, 1960. It was Tinguely who introduced Spoerri to this Paris community and opened up a rich network of connections for Spoerri that would include Rauschenberg and Manzoni. It is this feature of a strong sense of artistic community among the younger generation that distinguishes in part the European artists from their counterparts in the United States.

The art scene in the U.S. in the 1950s and 60s encouraged the idea of the artist as an alienated genius, which the Europeans, and many Americans in Europe, were so adamantly fighting against. Spoerri’s exhibition at the Galerie J depended, in many ways, on the community bonds of the Paris art scene. It involved the exhibiting of more picture-traps, but the source for these works was the restaurant that was opened and run out of the gallery for the first two weeks of the month-long exhibition.

Ten meals were prepared by Spoerri between March 2 and 13. Each of these evenings saw art critics acting as waiters. Each day a table was trapped and made part of the subsequent exhibition. As simple an idea as it may seem, the whole set-up of the restaurant addressed a plethora of issues, again related to the art world and its institutions.

In other words, the restaurant was a metaphor for the contemporary art scene. The artist as chef prepares and presents his wares to the public, with the art critic serving as an intermediary. The success or failure depends on the consumption of the meal, on the preference of “taste” of its consumers, and the word of mouth that follows.

It must be noted that each of the diners centered on a unique menu, thus preserving something of the aura of originality of the work, or meal in this case. The success of the meals prepared and served at the Galerie J, and their power as a critical metaphor that encompassed many of the themes Spoerri had tackled in past works, resulted in Spoerri hosting and preparing a bevy of banquets throughout his long career with the most recent occurring in 2002. Buhalterines apskaitos paslaugos Vilniuje – buhalteria.lt.

Despite the success of the dinners prepared by Spoerri on the occasion of his Galerie J exhibition, and those that immediately followed it, Spoerri’s frustration with the contemporary art market and its institutions continued and finally boiled over in 1967. He left Paris to live on the Greek island of Simi, where he remained for 13 months.

On his return to Europe, Spoerri settled in Düsseldorf where he opened his own restaurant on June 17, 1968, and a gallery above it. It was while in Greece that Spoerri realized that the preparation and consumption of food are two of the most defining acts of human existence.

In fact, in a speech given on the occasion of one of his banquets in Düsseldorf, Spoerri pointed out that humanity has two basic impulses, survival and reproduction, or, to put it more crudely, as Spoerri did, eating and fucking; he decided to focus his art on the former since, as he told his audience, the latter had been so much talked about already.(Daniel Spoerri, “Petit discours à l’occasion du Banquet Henkel, 29 octobre 1970,” Restaurant Spoerri, p. 88.)

There was not much novel about this since Spoerri’s work had predominantly revolved around food. The novelty would be his decision to focus on the theme through the establishment of a restaurant, and the development of a philosophy, or “gastrosophie” as Spoerri would put it, around the act of making and consuming of food. If anything, the Simi period and the subsequent opening of the Düsseldorf restaurant represented a consolidation of Spoerri’s ideas around art and its making, centering on consumption both literally and figuratively.

The preparation, serving, and consumption of food, for Spoerri, functioned as a metaphor on several levels. Obviously, the activities at the Düsseldorf restaurant were a metaphor for change, process, metamorphosis, in short a type of gastronomical alchemy, and obviously all part of the cycle of life in both a crude materialist sense and a metaphysical one.(Kamber, p. 37; and, Besson, pp. 9-19. The cycle of life idea is a point made most obvious in the film Resurrection mentioned earlier.)

On another level, they touched on the status of the art work and our perception of its value and the institutions that surround it; issues discussed already in relation to the Galerie J restaurant. The Düsseldorf activities paralleled and parodied the creation and consumption of art quite literally as evidenced by a number of the Eat-art exhibitions held in Spoerri’s gallery of the same name.

For some of these exhibitions, Spoerri had artists either create or allow the creation of food based on their work. One could purchase a work for a nominal price, most often simply based on the cost of the materials and the labor-time required to make the item, and obtain a certificate of authenticity from the originating artist.

In turn, you could consume the work literally, or try and preserve it, which would be almost impossible; however, by trying, one simply offered yet another example of the fetishization of the art object Spoerri so hated.

The publication of recipe books was another important aspect of Spoerri’s Düsseldorf-related activities. In itself, this was not so radical a gesture, however, in the context of Spoerri’s gastrosophie; it revived the idea of the prototype and its multiplication first addressed with the MAT Editions.

A recipe is something of a prototype that is often copied or rather multiplied, and which is never reproduced perfectly, either because of chance or the willful addition or substitution of ingredients.

In this, one finds a wonderful pragmatic formulation of the objectives of many of the Conceptual artists working in the United States at the time who decided to express their art in the form of an idea, choosing to let the viewer materialize it if they so desired.

The Spoerri restaurant in Düsseldorf offered above all a pretext for social interaction. There were fixed prices for the different menu offerings and one could eat for free if one were willing to be a waiter or wash dishes for a night.

Besides the meals as conversation pieces, and the themes some of these meals were built around, there were André Thomkins palindromes on the outside of the building, Spoerri’s correspondence used as wallpaper, works given by friends hung throughout, and a bookshelf that contained reference books and dictionaries for resolving arguments.

The interactions of Spoerri’s customers would be punctuated by the numerous rituals he constructed around certain meals and the types of behaviors and interactions that would evolve based in part on the cultural habits of the participants.

The special banquets organized in the restaurant and after it had closed merged perfectly Spoerri’s early ambitions as a stage director and his love for food and human companionship. In addition, the restaurant itself offered an endless supply of picture-traps that were exhibited in the Eat-art Gallery.

Even the restaurant itself became one of Spoerri’s most daring trap works as a portion of it was shown in a 1971 retrospective exhibition in Amsterdam. This work was, in a sense, a precursor of Spoerri’s most ambitious trap works, the Sentimental Museums.

Spoerri has produced four sentimental museums. Essentially, they are picture-traps of cities (the most recent occurring in Basel in 1989), although the slice captured cuts across time rather than space.

What is presented is an assortment of objects associated with a city, its history, and its people, that can somehow speak about them. The objects presented are valued for the stories they inspire rather than what they are as objects, whether it be the football from the last game of the season in Cologne or Heinrich Boll’s chewed pencils.

Unlike a traditional museum, the ordering of the objects tends to be alphabetical, thus discouraging any type of constructed, enforced narrative on the viewer.(Maïten Bouisset, “Daniel Spoerri, ou l’éloge de la curiosité [In Praise of Curiosity]: Interview,” Art Press (no. 197, Dec 1994), p. 47; Saner, p. 17; Kamber, pp. 69-73; and, Jean-Hubert Martin, “The “Musée Sentimental” of Daniel Spoerri,” in Lynne Cooke and Peter Wollen (eds.), Visual Display: Culture Beyond Appearances (Dia Center for the Arts: Discussions in Contemporary Culture, no. 10) (Seattle: Bay Press, 1995), pp. 55-67.) However, the sentimental museums really only gain their full value for the residents of the city the museum is devoted to, since only they can fully value and imaginatively feed off the context the various objects are part.

And again, like Spoerri’s restaurant, for example, these city-trap works are a nexus for socialization, fuelled and mediated by our deep-seeded cherishing of objects and the power of our imagination to construct worlds around them.

In closing, Spoerri’s Sentimental Museums are almost the perfect culmination of a career dedicated to opening our eyes and mind to how much the ordinary world around us is infused with our passions and obsessions, and that in the end this is what culture is truly all about. Read more information at this website