Irwin: Retroprincip 1983-2003

|

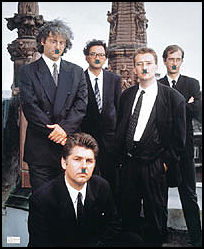

“Irwin: Retroprincip 1983-2003,” curated by Inke Arns (Berlin), presents an extensive survey in the work of Irwin, as well as a collective of Slovenian painters (Dušan Mandic, Miran Mohar, Andrej Savski, Roman Uranjek, and Borut Vogelnik), including some of the most influential artists from the former Yugoslavia.

Their artistic practice, as well as their theoretical writings and research projects, concern the following diverse subjects: the relationship between art and totalitarianism; modernist iconography and ideology; the geo-political impact of the revolutions of 1989-1991; and the historicising of modern and contemporary art produced in the former U.S.S.R., Yugoslavia, and Eastern Bloc.

The Irwin group fits into a larger constellation of artists, including members of the rock group Laibach, the theater/performance group today called the Kozmokineticni Kabinet Noordung, and the design collective, Novi Kolektivizem. These groups are known collectively as Neue Slowenische Kunst, or NSK.

Their members have been collaborating in a variety of forms since NSK was established in 1984. To understand the workings of this complex, one could see the members of Laibach as head ideologists, the theater as a kind of secularized church, and Irwin as state artists.

Irwin has said that the ‘retro-principle’ is “not a style or an art trend but a principle of thought; a way of behaving and acting.”

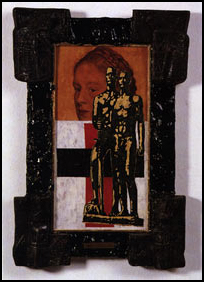

In their works, such as the icon, Malevich Between Two Wars, Irwin deliberately places modernist symbols (such as Malevich’s Suprematist black square or black cross) against totalitarian or fascist motifs.

Adding another layer of symbolic meaning, the Icons are contained in heavy frames, reminiscent of religious displays. Gregor Podnar (Ljubljana) curated the selection of Icons presented in the exhibition.

This strategy can also be seen in Mystery of the Black Square, one of Irwin’s group portraits. Irwin’s exploration in the aesthetics of politics, which was a key dimension of both fascist and totalitarian propaganda, is directly related to the politics of the former Yugoslavia.

Theorist Boris Groys commented in the catalog of the exhibition: “When the Irwin artists place quotations from European modernism and totalitarian art on the same level in their works and in their texts, they deconstruct the customary opposition of avant-garde criticism and totalitarian traditionalism with reference to the specific cultural experience of their countries.”

The dissolution of former Yugoslavia began in 1991. Slovenia was the first republic to gain independence, and the only one to escape fighting in the bloody Balkan Wars that followed.

The rise of nationalism in Serbia and Croatia, and the new political position of Slovenia as an independent state, became a main focus of Irwin’s work in the 1990s.

In the early 1990s, the ‘NSK State in Time’ was established. As Irwin explained, “NSK confers the status of a state not to a territory but to the mind, whose borders are in a state of flux in accordance with the movements and changes in its symbolic and physical collective body.”

In a clear critique of the problems of nationalism, citizenship, and the increasingly closed borders between the East and West, Irwin opened temporary consulates in Moscow and various cities in the United States and Europe.

People were invited to fill out an application form and were issued official passports as citizens of the NSK State in Time.

Another key element of Irwin’s work which has been produced since 1991 is the East Art Map—A (Re)Construction of the History of Contemporary Art in Eastern Europe (on-going).

It is an extensive research project that Irwin conducts in collaboration with significant curators and cultural figures in former communist countries.

Because of the relative isolation of artists working under communism, little to no research has been undertaken that attempts to incorporate the artistic movements and artistic production in the region from 1945 to the present in the art historical canon.

The East Art Map (exhibited as a publication, map, and CD-Rom) attempts to reassess the history of contemporary art as it was written in the West by examining the artistic production of Eastern and Central Europe, the links between countries in the region, and the theoretical discourses that connected various scenes.

It is perhaps the most concrete example of the extraordinary way that Irwin’s artistic and theoretical works have complemented and stimulated each other, and of the group’s deep commitment to assessing not only the past, but also the role of cultural production within political transformation.

“Irwin: Retroprincip 1983-2003” is an extremely important and timely survey, thoughtfully curated by Arns, who has written extensively on Irwin and NSK.

The catalog/anthology (published by Revolver, Frankfurt) and film program that accompany the exhibition provide viewers access to the art production and theoretical writings of NSK over the last two decades.

Hopefully the exhibition will introduce the work of Irwin and NSK to a broader audience, and will add to the critical debates they have so consistently generated.

More information can also be found at: www.irwin-retroprincip.de.