The Logics of the “Neglected” Center

1 Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art, January 28 – February 28, 2005, Various Locations, Moscow

“Our project, which happened to be the first of this kind in Moscow, presents the first alternative to the current formation of the Russia’s capital, which has been overlooked for a long time: this “neglected” center has never been integrated with the others. The logic of changes can form here recognition and glory of a new kind. This does not mean “again to conquer a central place,” but it refers to the assumption of “being in the center.”

To do a biennale, “to conquer the center place” again, is complicated. Putin’s Russia has lately been at the climax of a power consolidation, while for the outside world it consistently constructs an image of open country with the economic and political climate benevolent to arts and culture.

Funded by the government, under the patronage of the Ministry of Culture without any involvement from the private sector, the 1 Moscow Biennale featured a centralized system of responsibility (and irresponsibility), that was slightly corrupted and fully depended on loyalty to the authorities – all of this well fitted to the spirit of Russia today.

On one side, this curatorial claim was the necessity to continue the “biennale movement” and to enrich its history by embracing the most “neglected” regions and centers, such as exist in Russia. From another side, the unpredictable nature of biennales – enormous shows which generally tend to go beyond one’s control, as the idea of the arts conquering physical territory seems to be the most important – appeared to clash with the inflexible and outdated standards of Russian museums and institutions where it is sometimes impossible to put a nail in the walls because of the fear of devastating expenses afterwards.

The absence of public spaces in Moscow and the countless (quite abusive) police with smoking guns and metal detectors in the streets constantly create impediments and frustration that could provide material for artists (such as Clemens von Wedemeyer, one of the participants of the 1 Moscow Biennale), but are bad for the spirit and values that the biennale is meant to promote.

Some time ago, the reviews of the 50th Biennale in Venice (2003) included serious criticism for the lack of organizers’ control and adequate exhibition size – a disease that all biennales usually suffer from.

Oddly enough, in Moscow, the centralized organization compensated for the absence of curatorial ideas despite the main exhibition’s relatively small size (45 artists) and the involvement of famous curators (Joseph Backstein, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Yara Bubnova, Daniel Birnbaum, Rosa Martinez, Nicolas Bourriaurd) and major Moscow museums (Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, State Museum of Architecture, National Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow Museum of Photography and Moscow Museum of contemporary art).

As for the latter, only two of them – the Moscow Museum of Photography and the Tretyakov Gallery – devised their own projects; others became Biennale venues as a result of negotiations between the Biennale’s organizers and the city’s cultural authorities for venues across town.

The main exhibition at the Lenin Museum demonstrated such powerlessness through the lack of curators’ definite positioning towards the Russian context – an important factor, which usually surfaces strongly as soon as somebody attempts to disregard it.

For example, 1 Moscow Biennale failed to use its platform to address the situation around the ongoing trial of Moscow curators and artists involved in 2003 notorious show “Watch Out: the Religion!” (the hearing went on at the same time with the Biennale). “The context” arose again when a group of radical orthodox believers filed a lawsuit against the one of the Biennale’s special projects, exhibition “Russia 2” organized by Marat Guelman.

However, despite a handful of politically motivated works presented in the main exhibition at the Lenin Museum, the “party line” was defined by the group “Blue Noses” from Russia, omnipresent in this Biennale (they took part in most of the special projects organized for the Biennale by the various Russian art institutions and independent curators). Blue Noses’ video, coquettishly hidden in cardboard boxes, showed scenes ranging from sexual obscenity to political mockery, created with an audio accompaniment – squealing and laughing – as viewers walked through the exhibition at the museum.

Indeed, witty and entertaining, Blue Noses’ video corresponded to the work of Austrian group Gelatin, “Zapf de Pipi,” which tried to make an icicle out of urine collected from the viewers lining up at the special platform to contribute to the piece. These two works were a good counterpart to the “bombs” of David Ter-Oganyan (“This is not bombs”) scattered in the exhibition at the Lenin Museum – sudden and witty metaphor of the Russian reality.

The laughter-inducing part of the biennale, undoubtedly, was successful. But as for the curators’ other intentions, so persuasively expressed in the major catalogue’s article, including to demonstrate the “clarity” of artistic gesture and thought and to return Russia a status of “center” and to define a place of Russian art in the standardized international art context – were all of these claims successfully met by the participating artists?

If the 1 Moscow Biennale’s curatorial team had succeeded in its promise to bring brand new international artists to Moscow, the choices of artists were so predictable, and the relations of most participating artists to contemporary Russia was purely staged.

Even one of the most appreciated works, film Leave by young German artist Clemens von Wedemeyer, which was shot in Berlin particularly for the Biennale and meant to be “about Russia,” was emptied of any artist’s reflections on the actual Russian context. Actors (mostly Russians found by Wedemeyer in Berlin) performed in kind Kafkaesque situations in the countryside of Berlin – with police checkpoints and searches and the frustrated characters repeating phrases while stuck on some border – all of this could remind viewers of the tradition of experimental Russian films of the beginning of the 90s, informed by Tarkovsky and Sokurov. Nevertheless, they do not create any significant narrative and limit themselves to a number of cliché phrases and repeated, recognizable situations.

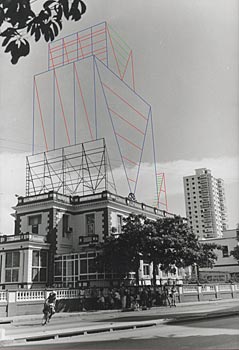

Among the serious works in the Biennale, there was “Let’s Put the Political Words into Action, Finally” by Carlos Garaicoa Manso (Cuba, 2004). Architectural photographs and collection of postage stamps, which represented the historical friendship between the peoples of Cuba and USSR, are meant to correspond to the utopia not so long ago embodied by the Lenin Museum. But the beautiful “song” about the socialist past “sung” by Carlos Garacoia did not really match the shabby and abandoned look of the former Lenin Museum, which demonstrated the desire to forget its past rather than to recuperate it.

Indeed, Russia has been consistently revealing a tendency of getting rid of the past, and this was felt in nearly everything in Moscow during the Biennale. In the beginning, when reading the Biennale program at the Lenin Museum, I did not pay much attention to the addition of the word “former,” but after noticing it, I started to wonder why it was so important to add this word, to remind viewers about the old storage of the Soviet history twelve years after the Museum was closed by Yeltsin’s government.

Why decide to keep the museum’s old name? What is more important, the Lenin Museum itself, or that the museum is “the former”? Or it was just an attempt to point out the time lapse, during which Russia has been falling between the memory and stereotypes, on one hand, and complete oblivion of the past, on the other. Probably, as a motivation of this name, the curators pulled Michael Romm’s dusty documentary, “Lenin is Alive” (1958) from the archives and made it a part of the main show.

It is a pity that a good work by Johanna Billing, Project for a Revolution (Sweden, 2000) was barely visible because of the lack of proper conditions to show video at the Lenin Museum. Showing precisely the generational attitude, idealism, and helplessness of the “new left” movement and contemporary activism, this work somehow corresponds to the attempt to shake those suspicious and hostile to any freedom of expression Russia by staging “revolution” in a form of unrestrained art creativity. Even badly installed, this work was suited to the general atmosphere of biennale shows: full of expectations and frustration, hope and its absence, its desire to move on and its lack of goal.