New Photography from the Caucasus at ifa-Gallery (Stuttgart)

Spot on… 9 September – 23 October 2005, ifa-Galerie, Stuttgart.

Spot on… is the name for a series of exhibits instituted by the German ifa-galleries that selects pertinent works from previous Biennales and various photography festivals, with a preference for works from more “exotic” countries.(Past examples have been the Sharjah Biennale and Noorderlicht, presenting Arabian photography.)

The last Spot on… exhibition presented recent developments in Caucasian photography from Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Armenia. The focus of the exhibition was “to examine the subject of authenticity in photography from the perspective of the ‘documentary’”(See the web-site of the exhibition: http://www.ifa.de/galerien/kaukasus/eindex.htm) (in different individual approaches) and to highlight ongoing processes in the art-spheres of the Caucasus today.

Apart from that, the curators of the exhibition wanted to influence the discourse of the documentary, a key issue in post-Soviet photography, in the regional context.(See the interview, which is added to the German web-site of the exhibition: Interview with Wato Tsereteli, the Kurator der Ausstellung “Utopia – Zum Dokumentarischen in der kaukasischen Fotografie,“ http://www.ifa.de/galerien/kaukasus/mehr_tsereteli.htm) This lays an emphasis on the international art communication, according to the fact that many of the artists entered the international art market long before.

Usually such a move of including formerly less-visible countries in recent art exhibitions is linked to the task of teaching the audience some additional “history-lesson” – i.e. regarding the largely undigested political processes that unfolded in the countries of the former Eastern Bloc over the past fifteen years.(On the political level, the increasing interest in non-European art everywhere is quite possibly a reaction to the steady focus on the European Union and its constantly expanding borders.) (Like that, for example, the Central Asian pavilion in Venice presented last year).

This task is made difficult by the fact that these countries often try to discourage a viewpoint that reduces them to a single post-communist space or condition. One way to strengthen national identity in the countries of the Former Eastern Bloc has been the active promotion of folkloristic “national” traditions instead. In fact, even more influential for the art spheres today were the active exchanges between younger artists from Western and Eastern Europe and the support of, for example, the Soros Institutes, themselves a typical post-Soviet phenomenon.(Today, artists from the Caucasian region try to focus their attention on their new geo-political role by addressing, among other things, the interests of the big oil companies. In this way, the exhibition of South-Caucasian photography organized recently by the Media Art Farm – Institute for Photography and New Media (“Appendix”), that is described in more detail in the catalogue, reflected on the region, its multicultural character, and its role in the modern global context. – The word “appendix” of course refers to a seemingly useless part of the body that still retains some important functions. It resembles, for example, Afghanistan, a country that that has become ageo-political battlefield incorporated by the World Bank and transnational companies. “Appendix 2 – diffusion and topology“ which took place in Tbilissi 2003 already included artists from Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland and France, as one of its aims is the fusion of the international art process and information.(see: Khatuna Kabulani, Zur Situation der zeitgenössischen Kunst in Georgien. Einige Anmerkungen in, p. 34-41).)

All of the “former Eastern European Countries” share an active quest for inclusion and exchange within the European and international cultural sphere. Additionally, they still preserve a history of close interconnectivity of all spheres from their common Soviet times. Shaping the future means re-collecting pre-Soviet values as well as dealing with the Soviet past and the post-Soviet present.

The exhibition did provide a wealth of information about the countries represented, such as links on the ifa-Gallery’s homepage on various subjects. Also, the catalogue contained many interesting articles regarding the post-Communist years and made it easier to situate the works on show. Indeed, post-Soviet photography in the Caucasus has been, first and foremost, a crucial instrument for the decoding of Soviet propaganda, especially in its use of documentaries.

While in social-realist photography the artist had to envision the beautiful future already in the (documented) present – often at the cost of some obvious falsifications (many soviet photographs are quite known for) – post-Soviet photography seems instead to look back to the Soviet or pre-Soviet past and its visual codes that became a starting point.

Photography, in this context, seems to have a double task. On the one hand, it guards against the Soviet past; on the other hand it also invokes that past nostalgically.(The text by Teymur Daini in the catalogue is a good example for the existing common socialist background and its nostalgic aspects; the curators relate to the exhibition as well. (Teymur Daini, Hoffen auf die Zukunft, Zur Entwicklung der aserbeidschanischen Kunst und Fotografie in den letzten zehn Jahren in: Utopia, Zum Dokumentarischen in der Fotografie, ifa (Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen e.V., p. 22-33).) Referring the viewer to the common Soviet past can sometimes include a critique of new types of consumer culture in the “post-communist” countries.

The individual artists’ “interpretations of reality ranging from reportages, to the photographic pursuit of a theme, from fragmentation to arranged photography simulating to be a document,”(See the web-site of the exhibition: http://www.ifa.de/galerien/kaukasus/eindex.htm) derive from traditional aesthetic pictorial modes as well as “explicit” symbolic uses of the medium.

Some of the actual pictures in the exhibition display its not-so-delightful past even in brighter colors. Still others with very peaceful impressions do not refer to any societal situation at all.

So, besides the exhibition’s investigation into documentary, the word “utopia” in the exhibition title referred both to the main questions posed by the exhibition and to a concrete situation. According to the interview with the curators, Barbara Barsch and Wato Tsereteli, it was meant to evoke the way such a utopia contrasts “with the dominant representations of disorder” in terms of hope for a peaceful life or how it becomes a ‘no-place,’ “a more fundamental questioning of representations of truth, a state of mind.”(In the interview, quoted above.)

Some of the photographs on show are traditional, others inherently postmodern. Overall, what mattered most to the curators were individual artistic approaches, in a rather wide variety of “documentary modes.”(“…people will ask: why is this documentary? And this question touches one important aspect of the exhibition: It enables the viewer to experience the medium from very different angles…“ (again Wato Tsereteli in the interview on the website).) (The “contents” of the images may or may not enter into this equation.)

The exhibition itself does not offer much commentary. Very few images on show can be “understood” only with reference to the titles (that might alter their first impression). This also gives the spectator some room for deciding whether or not to deeper engage into the backgrounds of the motives.

The photographs include both black and white and color; most of them represent a series, while others include a performance element.

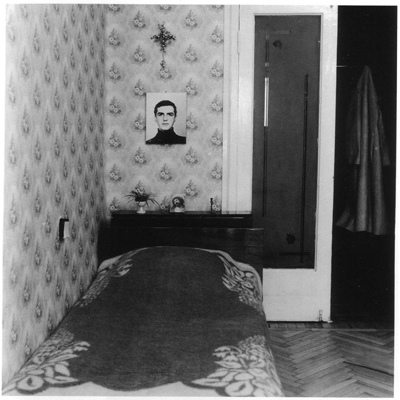

The first series of images are photographs by Irina Abzhandadze (Georgia) who documents brutal murders of young men and women in her country (committed on open streets) by capturing traces of the victims arranged inside the homes of their families. Her black-and white pictures resonate strongly with compassion and protest.

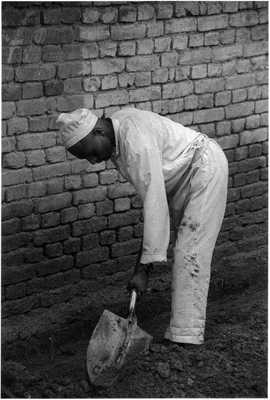

Rena Effendi’s photographs offer a similarly eloquent take on life: these works, in black and white as well as color, might be considered more “traditional.” Effendi’s socially engaged work captures people in derelict circumstances and investigates, according to Teymur Daimi, “their state of mind in the way it connects with the materiality of their surroundings.“ Two color images, in particular, are noteworthy for their ambivalence and complexity:

Old Woman With her Favorite Disc shows a poor but “colorful” kitchen that fits into the composition as if by chance. The soft colors make the Soviet-educated woman look even more humane and inspiring in comparison with the world presented in the other photographs. This could no doubt easily be understood as a kind of nostalgia for Soviet times.

House for Sale is the title of the other image, a well-composed photograph, again rendered in soft colors, that is turned into a social critique only by dint of its title. The all-too warm colors together with the slight smile on the face of the middle-aged woman in front of her house give the picture a delicately ironic, bitter undertone.

Photographs of Baku by Mekhti Mamedov (Azerbaijan) continue the play between black/white and color. This time, going back and forth between black and white and color photography works in the service of what we might call a “traditional” counter-history of the old city-center through its architecture.

Baku’s old center has in fact long since commercialized, a fact that becomes visible through the mixture of old and new streets documented by Mamedov. Upon second glance, the appealing corners of the old streets seem to conquer the newly renovated buildings. At the same time, the triumph of the old houses over the commercial sites touts Baku’s status as a city and its Mediterranean atmosphere from the vantage point of a tourist.

The diverse photographs of Natela Grigalashvili (Georgia) present moments of life some place, but they do not point to any specific region. This makes them pleasant and interesting to watch, but Georgia’s desperate economic situation comes into view only in the most marginal way.

Landcapes dominate the vast deserts filled with a post-apocalyptic atmosphere in works by Sevinj Pirizadeh-Aslanova (Azerbaijan). They are equally well composed (in a traditional manner). Unlike Grigalashvili’s, Pirizadeh-Aslanova’s photographs do take note of the tattered fabrics of the country and its poisoned land, poverty, and social disorder. A great amount of the artist’s composition derives from depicting their “natural” colors.

The series of pictures by Armenian photographers Albert Babelyan and Ruben Mangasaryan are heavily laden with symbolic meaning. They both place the instruments of war into their lively scenes in a very conspicuous fashion.

The Dirt series by Serj Navarsardyan gives us (sometimes unfocussed) glances at the dust and dirt that emerges when the streets are swept. In this case, only the commentary can explain the special significance of this dirt. It functions as a symbol of Armenia’s problematic self-conception in the wake of its isolation during the Karabakh-crises with Azerbaijan.

The performative element comes to the fore in Georgian photographer’s Gela Kuprashvili’s impersonations of a soldier, a guru, and other such figures. The punch line of his works is that the picture title never matches the scene depicted in the image.

A video-work by Rashad Alekberov (Azerbaijan) and the series of photographs showing a performance by Nino Sekniashvili (Georgia) refer to the changes in the representational modes that occurred in the Caucasian art scenes, switching them towards greater emphasis on international communication. In his video, Alekberov montaged himself in relation to historical figures; text and picture fuse randomly.

All in all, the exhibition demonstrated that traditional modes can still be very successful in contemporary photography.

By altering modes of documentary representation through historical and aesthetic means, which is apparent in Caucasian photography, the key questions of the medium about its authenticity stay as vulnerable as ever.

Thankfully, another main function of the documentary – the raising of interest into the world as it is, yet sometimes not rendered conscious (or even unknown) – finds itself realized through exhibitions like this in the best way.