Modernities Out of Sync: The Tactful Art of Anri Sala

Anri Sala(In our conversation in Venice in April 2008, Anri Sala and I tried to define tactfulness and failed over and over again. I decided to record our informal interview in a hope of a future intellectual revelation. Upon my return home I discovered that my interview was missing sound. Inadvertently, our interview ended up being off the record, and all I had were scribbles on a sheet of paper, variations on the theme of impolite tactfulness. As we got more and more lost on Venetian streets with names like Calle Amor dei Amici and Calle della Vida, we realized that we could only come up with definitions via negatives. Tactfulness is neither “loud visuality” nor spectacular clarity. Nor is it the art of caution. Tactful art is not driven by the plot but by unexpected detours and details. It doesn’t move fast and exceeds the frame. Tactful filming defies a complete authorial control or mastery of the ceremonies. Tactful art is neither quite sacred nor profane, neither messianic nor eschatological. What if tactfulness should not be defined by neither/nor but by and/and or almost and yet?) described to me how during the historical changes in his native Albania in the early 1990s every member of his art school class became a belated avant-gardist: “Suddenly, there was one surrealist, one expressionist, and one cubist, and I continued with my interest in the fresco painting.”(Personal interview with Anri Sala, Venice, 21 April 2008.) The uncontrollably fast pace of historical changes provoked in the artist a desire for a slow and concentrated attentiveness. Fresco art was not about individual signature but about techniques of layering paint and learning how to apply and retouch, working through time and the material. This was not a retrograde gesture or nostalgia for some artistic roots, but a desire to carve a space for a singular artistic exploration that was a little out of sync with the urgencies of the current moment, though it was also inspired by it.

Soon after mastering fresco painting, Sala took on video art but he remained interested in layering images and capturing disappearance in progress. His videos take us to the perimeters of modern projects, from the half-ruined socialist apartment buildings to the Senegalese radio studio with a lonely butterfly in the corner. They record linguistic untranslatabilities and missing landscapes. In Sala’s world, historic ruptures and scars turn into ellipses and sensory gaps that are present in most of his films. His is not merely the art of memory but also the art of surprise and of the translation/transposition of experience into an artistic dimension of asynchronous existence, using images, music and light that are often on the edge, offbeat, and occasionally off-color. Perhaps Sala, like his classmates, became a belated modern artist at the turn of a different century and after postmodernism. His project is a part of those eccentric modernities that come from the border zones of Western culture and enrich it from the edges.

The contemporary cultural moment can be described as a conflict of asynchronous modernities, of various projects of globalization that are often at odds with one another. The prefix “post” in this context seems to me somewhat passé. Instead of fast-changing prefixes such as “post,” “anti,” “neo,” and “trans” that try desperately to be “in,” I propose the use of “off,” as in “off-kilter,” “off-Broadway, “off-course,” “off-brand,” “off the wall” and “off-color.” “Off-modern” is a detour into the unexplored potentials of the modernist project.(On the conception of the “off-modern,” see Svetlana Boym, “Off-Modern Manifesto,” at www.svetlanaboym.com and The Architecture of the Off-Modern (Columbia Buell Center/Princeton Architectural Press, 2008).) It recovers unforeseen pasts and ventures into the side alleys of modern history at the margins of error of major philosophical, economic, and technological narratives of modernization and progress. Off-modern follows a nonlinear conception of cultural evolution. It could follow spirals and zigzags, movements of the chess knight, or parallel lines that can occasionally intertwine. Or, as Vladimir Nabokov explained, in the fourth dimension of art, parallel lines might not meet, not because meet they cannot but because they might have other things to do.(Vladimir Nabokov, “The Overcoat,” in Lectures on Russian Literature, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1982.) As we veer off the beaten track of the dominant modern teleologies, we have to proceed laterally, not literally, and discover the missed opportunities and roads not taken. In fact, the preposition “off” developed from “of” in an emphatic and humorous onomatopoeic exaggeration that imitates oral speech. The “off” in off-modern designates belonging to, or “of,” the critical project of modernity as well as its edgy excess, marked by the second emphatic “f”. To some extent, off-modern art is closer to modern art in its unforeseen, forgotten, and non-institutionalized dimensions. Off-modern art has both temporal and spatial dimensions, as it is belated and out-of-phase with the supposed progress of history and also eccentric vis-à-vis the familiar centers of modern/postmodern culture. Only when one dares to be a little off or even outmoded can one become truly contemporary.

Off-modern art suggests an alternative understanding of the relationship between aesthetics and politics and a somewhat different artistic etiquette. “How can one be tactful but impolite?” wonders Anri Sala. We do not find any shit of the artists or of elephants in Sala’s work, no bright red of the images of Lenin or Coca Cola, no chic dogma of artistic mastery. His method is defamiliarization, but not of a Brechtian or conceptual kind, but more as an exercise inaesthetic estrangement, wonder, and surprise. Sala’s works might appear a little out of sync with some of contemporary art’s historical paradigms, offering powerful challenges to them. His art is on the edge but not marginal, playful but not scandalous, tactful but impolite. I would like to explore this edgy tactfulness and the off-modern poetics and politics that result from it.

“Tell me that this country doesn’t exist,” commented the artist Liam Gillick after watching the rushes of what was to become Sala’s film Dammi i Colori. But it is, in fact, much more interesting that the country which looks stranger than fiction does exist. In Sala’s words, Albania is not even considered “the other” of the West; it is the unknown. It does not even get to be called a “mystery wrapped in enigma” — to quote Churchill’s words about Russia. Albania makes only a few cameo appearances in the recent Western artistic imagination, sometimes as a make-believe land, conjured up for the sake of political hoax, as in the film Wag the Dog.(The premise of the film is that the American president fabricates a fictional war to save his presidential power. It is ironic that it actually went the other way around. In the 1990s, inflated American domestic scandals distracted the attention of the president and his advisors from the very real political situation in Kosovo and in Albania that was unfolding outside media attention.) The story of Albanian art hardly fits into any paradigm and when it does, it tampers with the paradigm itself, turning it upside down. Albania is postcolonial, only it was colonized by the Ottoman Empire and later by the Italians; it is postcommunist but we have to keep in mind that it was here too offering an exceptional example even within the communist universe. It was both most faithful to the Stalinist vision thirty years after de-Stalinization in the Soviet Union and eccentric and isolated even within the communist world. Albania, “the poorest country in Europe” (in the words of Edi Rama, the mayor of Tirana), was also a border zone between East and West, South and North, Islam and Christianity. Sala told me that, during the years of the dictatorship, artists in Albania were not “just” placed in the Gulag as some were in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, but they were prohibited to paint, forever. So there was no tradition of nonconformist art here that existed in the “grey zone” the way it did in the Soviet Union or Eastern Europe. “One could become an enemy of the people for commenting about the lack of fish in the market or for painting the shoe in a wrong way,” comments Todi Lubonja in Sala’s film Intervista. And yet, in spite of its imposed artistic isolation, Albania had its own project of modernization and a rich culture, with interesting cinema and art practiced against all odds and much everyday creativity.

Any artist or writer coming from an eccentric background (eccentric vis-à-vis the West European/American mainstream) knows how difficult it is not to be placed in the category of “friendly exotic other” and thus to become forever a hyphenated artist with national qualifiers. These artists were not necessarily framed by their contexts but often exceeded the frame. Today, Sala is an international artist, a wonderer, a border-crosser, an explorer, and a tourist. Yet his fascination with the edges of language and image and his resistance to both explicitly political and commercial speech might have been shaped by his early encounter with life under the dictatorship, with its hidden violence and perversion of language in the public sphere that sometimes went together with intimate and rich friendships in private. The scars of memory and history in Sala are not to be rapidly healed but to be touched upon over and over again — tactfully.

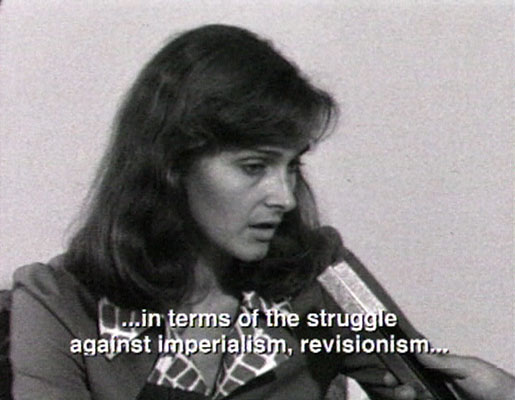

One of Sala’s most celebrated early films, Intervista, is a story of memory out of sync. The film begins like an Albanian version of Blow up (or Blow out) and then turns into a personal history/detective story. At the opening of the film the young filmmaker discovers film footage from the 1970s that shows his mother, Valdet Sala, as a young communist standing right next to the Secretary of the Albanian Communist Party, Enver Hoxha, and talking with heartfelt enthusiasm. However, the sound is missing.

Valdet cannot identify the date of the interview and has no recollection of the occasion, but she recognizes the interviewer, Pushkin Lubonja, who leads the filmmaker into the labyrinths of the Albanian art of memory. Lugonja explains that he does not remember the interview with Sala’s mother either, because it was ultimately unmemorable and not meant to be remembered. He says that he made more than 2,000 interviews and there was hardly any singularity to them. The questions were “foreseeable and so were the answers.” We are not dealing with the Western memory industry here but with the peculiar ars oblivionalis, the art of forgetting, that generates false synonyms of the original event and a further obfuscation of language that substitutes for the experience.

The local party leader Todi Lubonja manages to date the film footage through a curious technique of anticipatory erasure that was described in Milan Kundera’s The Book of Laughter and Forgetting. He identifies some political actors in the footage who were not yet airbrushed from Albanian history (i.e., not yet executed, imprisoned, or erased from all the photographic documents. Todi Lubonja and his wife were arrested soon after this interview and spent 16 years in prison). This glitch in communication, or sensory gap, inspires Sala’s quest. He locates the soundman of the footage, a veteran of Albanian cinema, now a taxi driver/philosopher bracing the streets of Tirana. The man explains that in the 1970s they always filmed “out of sync” but, at the same time, they were well aware that the failure of synchronization and any technical glitch could become a crime against the state that could cost the filmmaker his job and occasionally his freedom or worse. In those days the soundman lived in fear, quite different from the everyday fears he faces on the streets of the postcommunist city; that other, old fear, during life under the dictatorship, was a “fear without an end that accompanied one till the death.” Giving up on finding the recorded sound, Sala does not give up on his cinematic andpersonal adventure. His film becomes a story of “glitches” — technical, linguistic, mnemonic, communicative. Sala decides to read his mother’s lips — literally — with the help of deaf and mute translators.

But what kind of revelation could come from reading his mother’s lips? Is there a dark secret, a corpse hidden in the missing landscape? In the next encounter with his mother, the artist shares with her the results of his reconstruction. This is what she is saying in the early footage:

This meeting was held to express a clear support of the country in the struggle against imperialism and revisionism and the two superpowers which is only possible if the youth unites under the guardianship of the communist party.

Valdet’s reaction is bewilderment, embarrassment, non-recognition: “It’s absurd,” she says, “not the ideology but the grammar. I know how to express myself.” It is curious that she reacts to the glitches in grammar, not to the subject matter. “Read your lips, Mom, there are no cuts here,” says the filmmaker. His technique is the very opposite of the conventional documentary or of Socialist realist-style footage, which always hid its devices and circumstances of filming. Instead, Sala documents every step in the process of translation, exposing rather than retouching the blind spots, black holes, and gaps. The sentence that his young mother recited is not so revelatory, but rather foreseeable and unmemorable.

Having grown up with a similar media culture in the former Soviet Union, I remember how we mastered the unwritten laws of mythological communication. Usually, at the beginning of such ritual speeches, there were declarations of revolutionary unity in the face of the enemy and then came an appeal to persecute the enemies of the people. This would have been a more embarrassing revelation, but the filmmaker has no desire to go there. “Does it bother you that I am filming this?” asks the filmmaker. “I don’t know. I have mixed feelings. It was not black and white,” replies Valdet. She speaks about sincere belief and concrete achievements in modernizing the country that went hand–in-hand with the “mass hysteria” of the congresses, which made it difficult to draw the line where revolution ended and the compromise with power and with oneself began. The words about the “world revolution” still have “a nice ring to them” for her. Her speech in the footage is refracted by the more direct opinions of the other participants in the interview, which add nuances of historical understanding. Intervista is a “personal project” but it does not fit into the genre of identity quest (the “young Albanian artist returns to his homeland in search of his roots” genre film) nor is it a psychoanalytically inflected confrontation between mother and son. We never find out if Valdet thinks that she has ever compromised herself. In Sala’s reflection on history and memory out of sync, “mixed feelings” predominate. It is possible that the recording of such confusions in a “non-black-and-white” manner constitutes an approach to the traumas of history that is different from the approach that characterizes art from the other parts of Europe. Sala holds the language of clarity in suspicion and tries to undercut its seductive syntax. At the end we realize that the topic of Intervista is not the deciphering of Valdet Sala’s old interview but a continuing interview/conversation between the mother and the son, which involves a change in syntaxes. Instead of a scene of unmasking we have a scene of intimate communication and a tactful cinema of deep affection.

For me, one of the most cinematically striking features of Intervista is the fact that here the life-shattering revelations are uttered as if off-camera or off-the-cuff: “We lived 50 years under dictatorship. Dictatorships don’t expose evil, they hide it. They hide the crime,” says Todi Lubonja. We notice that he is not looking into the camera. The corner of his face is framed by the rim of his dandyish old-fashioned hat and the invisible picture on the wall. The artist makes the camera as unobtrusive as possible, letting Mr. Lubonja talk away. Then, in the editing room, he makes a conscious decision not to cut from the film this awkward image “in sync” with the sound. For Sala, seamless narratives, conventionally effective cinematography, and clarity are part of the spectacle of “hiding the crime.”

In his most serious conversation with his mother, Sala decides to film this segment himself, without his cameraman, so he can speak with his mother tête-à-tête in the intimate setting. She is on the couch, but this is no psychoanalytic cinema. Her face is shot in an extreme close-up but at an angle almost reminiscent of Ingmar Bergman’s Persona. The closeness does not offer revelation; she speaks about her ambivalences, fears, and mixed feelings. Her face against the dark background appears almost like a mask behind which certain things remain inscrutable. Sala exposes the edges but does not jump into the abyss, he reveals the place of the scars but he does not wound further. Nor does he offer an unaesthetic stance against memory and history; he proposes instead a tactful yet very unconventionally aesthetic treatment. For Sala, tactfulness is not only a way of relating to the film’s cinematic subjects but also to the medium of cinema itself. Tactfulness is respect for the fragile boundaries of the other but also an intimation of the untouchable and unpredictable. Sala’s tactfulness is not reverent, pious, or cautious; on the contrary, it is mysterious and alogical. Tactfulness might hold the secret to Sala’s films but it is also a mystery in itself. It is not very often that one hears theword “tactful” in the context of contemporary art. Could it be that in a culture that demands either corporate caution or sellable sensationalism, there is a taboo against impolite tactfulness?

The word “tact” derives from “touch,” but at first glance, the concept seems to have reversed its meaning and come to signify a delicate distance and respect, a displacement of contact away from the domain of the physicality and into the domain of the sociability and aesthetic arrangement of everyday life. But this is only at first glance. The more we look into the problem of touch itself, the more ambivalent it becomes. It was Aristotle who observed the elusiveness and mystery of touch in his “De Anima.” Unlike the case with other senses, we do not know what the “organ of touch” is and whether it is superficial or deep, visible or hidden. Can touch really be only skin deep? Is there a mysterious psyche somewhere that guides us? Touch appears to be at once the most syncretic of all senses and the least representable, the most obvious one and the most difficult one to frame.

“Can we touch with our eyes?” asks Jacques Derrida.(Jacques Derrida, On Touching–Jean-Luc Nancy, trans. by Christine Irizarry, Stanford University Press, 2005: 2.) The organ and representation of tact are just as elusive as those of touch, migrating and escaping the frame, preserving the mystery. Tact for Derrida is a “sense of knowing how to touch without touching, without touching too much where touching is already too much.”(Derrida, On Touching, 66.) Tact, in other words, is connected to the art of measuring that which cannot be measured. Derrida sees at the core of tact a taboo against contact, a certain interdict or prohibition, an abstinence. But, in my view, in the case of artists from traditions other than those of Western Europe or the United States where historical violence is not an armchair fantasy, tactfulness is less about abstinence than about a conscious reticence, less about the interdict than about a deliberate choice not to violate further that which has been violated by history. It is a choice to touch without tampering, to play in the border zone without crossing it, to explore the shades of ambivalence. Tact points to the untouchable but also begs us not to forget the effect of touch, not to rush into the virtual or the transcendental. The tactile is still there in artistic tactfulness, which gives it a unique temperature, neither too cool nor too hot, but never lukewarm, either.

In fact, the spectacle of violating the inhibitions has become more conventional in contemporary art than in the tactful explorations of the border zones. In his A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments, Roland Barthes observes that in contemporary culture the pornographic and transgressive have become so common that they are no longer unusual; in fact, our affections, frustrations, and sympathies are more obscene than Georges Bataille’s tale of the “pope sodomizing the turkey.” Barthes suggests, “Whatever is anachronistic is obscene. As a (modern) divinity, History is repressive, History forbids us to be out of time.”(Roland Barthes, A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments, trans. by Richard Howard, New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1978: 177-178.) What is obscene, then, is what is off the scene, and tactfulness seems to be off the contemporary art scene.

Tactfulness affects artistic conceptions of time, space, language, narrative, and even the temperature of communication. It operates through tactics, not strategies. Tactfulness takes time; it introduces a different temporality that is deliberately not in sync with the pace of contemporary media culture and digital instantaneity. It slows the communication. It dwells in the non-signifying and non-symbolic spaces of conversation, in the interstices of language. These include technical and communicative glitches, moments of embarrassment, of sudden fear or astonishment, and all the other uncodifiable moods. Tactful art does not repress but represents silences in communication and the shimmer of revelation and concealment. Tactfulness is one of the elusive tactics that Sala uses in his way of treating the cinematic frame itself. He is not trying to control the visual or conceptual field. On the contrary, he says that, for him, fiction (in the broad sense of the word) should overlap but never coincide with the cinematic frame. “It would be like setting all the conditions for fiction to happen but then record it as if we arrived a bit too late,” remarks Sala. In other words, the author dreams up a tactical map of the film, sets the scene, but then leaves open a possibility for surprise.

The untouchable and unpredictable are allowed to come in if there is space for them. It is in that space in which nothing is scripted — the “un-iconic” space — where the wind of the unpredictable can blow the frame and surprise the filmmaker himself. When the camera is tactful toward its subjects, it is not violating their boundaries but intimating their potentialities and the untouchable spaces around them. The filmmaker is not trying to instrumentalize the individuals for the sake of higher truth or a slick film, but to dwell in the mystery of communication. Tactful mediation takes place between respect and astonishment. Derrida observed that tactfulness is always about “touching the law” and therefore it is about the “endurance of limit as such.” The artistic tactic of tactfulness involves a continuous play with the laws of art, of language, of public space, of history, of memory. The most interesting form of tactfulness is not the one that leads to a comedy of manners or psychological subtleties but the one that questions the syntax of language itself and moves toward the alogical. This term goes back to the Russian avant-garde and one of its early proponents, Kazimir Malevich; only he did not stay there but marched on to suprematism and oblique figuration. It is the art of syncope, of ellipse and accent, that highlights the gaps that cannot be bridged without violation. In other words, the tactful art is the art of the syncope.

Syncope becomes both a metaphor and an offbeat rhythm for Sala’s recent works. What interests him is the way syncopation deviates from the strict succession of regularly spaced strong and weak beats and disorients “fictional” plots. “Syncope” has linguistic, musical, and medical meanings. Linguistically, it refers to “a shortening of the word by omission of a sound, letter, or syllable from the middle of the word.” Musically, it indicates a change of rhythm and a displacement of accent, “a shift of accent in a passage or composition that occurs when a normally weak beat is stressed.” Medically, it refers to “a brief loss of consciousness caused by transient anemia, a swoon.” Syncopal art dwells on sensuous details, not symbols. In fact, syncope is the opposite of symbol and synthesis. Symbol, from the Greek syn-ballein, means to throw together, to represent one thing through another, to transcend the difference between the material and immaterial worlds. For a tactful artist, symbols, metaphysical or sexual, “bleach the soul,” numb “all capacity to enjoy the fun and enchantment of art,” to quote Vladimir Nabokov. Syncopation is about the impossibility of transcendence and fusion. For Nabakov, personal exile and displacement determined the rhythm of his prose and in many was enabled his art: “the break in my own destiny [i.e., the experience of exile] affords me in retrospect a syncopal kick that I would not have missed for worlds,” he writes in his autobiography.(Vladimir Nabokov, Speak Memory, discussed in Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia, New York: Basic Books, 2001: 281.) Syncopation does not help to restore the lost home; it is present as a trace, as a foreign accent. What it accomplishes is a transformation of the loss into a musical composition, a ciphering of pain into art. The tactful rhythm of syncopation does not consist in leaving things intact, but in touching without violation, in revealing the dormant psyche of things, people, and cities without possessing them.

Sala’s method is estrangement, in the tradition of Viktor Shklovsky and the alogism of the avant-garde. It means distancing and making estranged, deferring the denouement, experiencing the world anew, or moving like a knight in the game of chess through the zigzags. Such operation suggests a cognitive ambivalence and a slowing down of action for the sake of the play and wonder that might open other dimensions and parallel universes that exist side by side with ours.

“I wanted to show images from the place where speaking of utopia is actually impossible and therefore utopian. I chose the notion of hope instead of utopia. I focused on the idea of bringing hope in a place where there is no hope.”(Hans Ulrich Obrist, “Conversation with Anri Sala,” in Mark Godfrey, Hans Ulrich Obrist, and Liam Gillick, Anri Sala (Phaidon, 2005): 133.) The place where speaking of utopia is impossible and therefore interesting is not an imaginary city out of Italo Calvino, but today’s Tirana. In Albania, the language of utopia, like the language of “the world revolution” that Valdet Sala speaks about, has been overused and has to be reframed in a radical yet tactful artistic manner.

Like Intervista, Dammi i Colori is an interview, in this case with Edi Rama, artist and mayor of Tirana and Sala’s friend and mentor. Dammi i Colori is also about touching, with paint and in broad strokes, the urban exteriors and interiors that transform historical scars. It is the story of a “dead city,” which after fifty years of communist dictatorship followed by post-communist riots and new, exciting, but anarchic democratization, resembled a “transit station” where people “were doomed to live,” and the remarkable project of transforming it into “the city of choice” that can be inhabited anew. How does Rama propose to do it? The way the artist does, cheaply and boldly, through color. He wants to use the color not as a symbol but as a signal and bold trigger for the future shared memories of the troubled city. His project is to retouch the facades of the city in the radical artistic manner, creating a striking visual form that will allow for a new kind of urban democratization. According to Rama, color therapy is not for every city:

Like Intervista, Dammi i Colori is an interview, in this case with Edi Rama, artist and mayor of Tirana and Sala’s friend and mentor. Dammi i Colori is also about touching, with paint and in broad strokes, the urban exteriors and interiors that transform historical scars. It is the story of a “dead city,” which after fifty years of communist dictatorship followed by post-communist riots and new, exciting, but anarchic democratization, resembled a “transit station” where people “were doomed to live,” and the remarkable project of transforming it into “the city of choice” that can be inhabited anew. How does Rama propose to do it? The way the artist does, cheaply and boldly, through color. He wants to use the color not as a symbol but as a signal and bold trigger for the future shared memories of the troubled city. His project is to retouch the facades of the city in the radical artistic manner, creating a striking visual form that will allow for a new kind of urban democratization. According to Rama, color therapy is not for every city:

I think that a city where things develop normally might wear colors as a dress, not have them as organs. In a way colors here replace the organs. They are not part of the dress. That kind of city would wear colors like a dress or like a lipstick.

Touching with color, then, does not merely change the “skin of the city” but transforms its internal organs and awakens its dormant psyche. Rama is not interested in color per se but in debating colors and in the ways in which public debates become a part of a new urban citizenship: “There is no other country in Europe where the color is so vehemently debated,” says Rama in the film. His wish was to join together the city of color and the city of public debate, creating a new model for democratic deliberations and shared histories.

For Rama the relationship between the mayor and his people is similar to that of the artist and his audience. This is not a case of the “aestheticization of politics” but rather of a transformative artistic practice that does not aim at creating a seamless spectacle. Rama defines his project as the “avant-garde of democratization.” The juxtaposition of the two words is crucial, if controversial. Democratizing goes together with “making artistic,” while avant-garde engages deliberation. In this sense, Rama’s project is a curious reversal of the Art of Monumental Propaganda that originated right after the Russian revolution. The color project can be called “The Art of Postmonumental Anti-propaganda,” and yet it is very much connected to many unfulfilled “lateral” dreams of the avant-garde without totalizing expectations. For the mayor, “artistic” becomes almost synonymous with “public”; he aspires to give his city a new agora and an aesthetic public realm. His project can be compared to that of another artistic mayor of a city of eccentric modernity, this time in Latin America. I am thinking of Antanas Mocus, the mayor of Bogotá, who used art and performance to unite and transform the city, turning law enforcement into a form of urban play. Mocus was a philosopher interested in the avant-garde and particularly in the work of Victor Shklovsky and his theory of estrangement.

Rama’s project might appear as a utopia of democratization. But it is certainly more imaginative and far less expensive than the realpolitik architecture of Potsdamerplatz in Berlin, with its corporate privatization of the public realm, or the rebuilding of the larger-than-life cathedrals and huge underground shopping malls and the nouveau-riche extravaganza of contemporary Moscow. Rama’s project is not that of restorative nostalgia; he does not erase the modern heritage of the city but reflects on the unfulfilled promises of modern architecture and art that can still affect life by bringing in emotion, pleasure, and care for the common world and for individuals. In short, this is a more modest dream than a large-scale collective utopia, but a dream worth dreaming.

Sala’s film tactfully estranges but does not demystify Rama’s work. Instead, Sala refracts the artist-mayor’s dream of color, creating his own portrait of Tirana between night and day, memories and hopes. At the beginning we see a beautiful nocturnal footage that frames the slices of the city like miniature masterpieces of abstraction. Then come the split shots that reveal the edges of the urban dreams between the mud and the colored facades, the ruins of the past and the construction sites of the future. Sala’s camera loves the ruins and engages in what I would call a paradoxical and future-oriented art of ruinophilia. The nocturnal shots, which offer an almost operatic transfiguration of the city, are intercut with diurnal shots, but the relationship between the two is not a form of ideological montage or some clear opposition. Some of the daily activities of Tirana residents comment on the new refashioning of their city. There is a boy running around in a colored mask, a man who coquettishly arranges his hair in a tiny mirror on the ruined wall, and another man who changes his costume — they are the new aesthetic urban dwellers humorously partaking in the dressing up of the city.

The film makes public vision intimate. It begins and ends with a single light, not with a total illumination. At the opening of the film we see the nocturnal street with only one window gently lit, as if there were a single intrepid romantic or insomniac eavesdropping on the transforming city (or is it the artist recording the nocturnal daydreamer with his camera?). The film’s ending is equally anti-spectacular. In the final sequence, the mayor appears to us as a private citizen and a painter who still enjoys the little surprises in daily life: “If you take the red from the car light and put it in the dark, it looks nice.” From grandiose visions we are back to a little epiphany, a moment of wonder and hope in everyday life, no more and no less than that.

Utopia is an impossible concept, but both Rama and Sala use it. Sala and (to some extent) Rama return utopia back to its origins — in art, not in life. Sala does not feel any embarrassment about things aesthetic as do some contemporary artists (and curators), for his aesthetic is a broad “exploration of the sensible” and a particular form of artistic knowledge and interplay of the senses.(I refer here to Jacques Rancière’s conception of aesthetics, in particular in The Politics of Aesthetics, trans. by Gabriel Rockhill (Continuum, 2005), and in his essay on Sala, “La politique du crabe,” in Anri Sala: Entre chien et loup — When the Night calls it a Day, Paris: Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris, and Koln: Walther König, 2004: 65-75.) Sala is less interested in the issues of artistic “isms” or institutional critiques that concern many Western conceptual artists; instead he is engaged in rethinking aesthetic practice in the broad sense and in opening the uninhabited spaces of language.

In all of his projects Sala disorients assumptions of contemporary art and theory. In his early project Déjeuner avec Marubi, Albanian women reframe the icon of Western modern art, Manet’s once-scandalous painting Déjeuner sur l’herbe. By dressing up the nude woman in Albanian clothes, Sala returns this collage artwork to Western audiences. In the film Làk-kat, shot in Senegal, he shows kids learning the words in Wolof that stand for the many gradations of whiteness and blackness. During our conversation, the artist observed that because of his Albanian background he does not feel that he fits into the Western colonial paradigm and that he is just as interested in what colonialism did to the Europeans, in this case to the French, as to the Senegalese. The film Promises also deals with the global circulation of language and linguistic embarrassment. Sala asks several Albanian men to repeat the famous line of Al Capone: “Nobody puts a price on my head and lives.” They do so with genuine discomfort, and there is something uncanny about the whole procedure, which makes the lines sound like a forgotten nightmare of the Balkan wars. The friends return Al Capone’s lines with a new cultural accent. Speaking about the relationship between “the West” and Eastern Europe, Sala describes it as a hypothetical dialogue, well-disposed but frequently one-directional: “When we [the fellow artists from Sarajevo, Tirana, Belgrade or Senegal] asked the West the questions they didn’t know the answers to, we had to rephrase our questions.” Through his films Sala turns the tables and asks us to rephrase the questions we ask of art, East or West.

The art of tactfulness eschews both the media-driven sensationalism of the new and of nostalgia and ostalgia alike.(For a discussion and definitions of nostalgia and ostalgia in the contemporary context, see Boym, The Future of Nostalgia.) If there is nostalgia in Sala’s film, it is not a longing for the particular lost homeland but for that slow time of one’s East European childhood that allowed for a long duration of escape dreams into the landscapes without propaganda and advertisement, those missing landscapes that have not been curated yet.

A different version of this essay was published in Purchase Not by Moonlight (exhib.cat. Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami, 2009, 39-53).